I am pleased to introduce to Big Picture readers someone I have known and admired for many years: Bruce Bartlett worked for Congressmen Ron Paul and Jack Kemp, and in the Office of Policy Development in the Reagan White House, and at the Treasury Department for George H.W. Bush. He is now a political independent.

Enjoy.

~~~~

Is The Only Purpose of a Corporation to Maximize Profit?

Bruce Bartlett

Abstract: Historically, corporations were expected to serve some public purpose as justification for the benefits and privileges they receive from the state. But since the 1970s, the view has become widespread that corporations exist solely to maximize profits and for no other purpose. While the shareholder-first doctrine was supposed to solve the agency problem, in fact it has gotten worse as corporate executives enrich themselves at the expense of shareholders. Moreover, the obsession with current share prices as the only measure of corporate success may be destroying long-term value as companies cut back on investment to raise short-term profits. Tax policies designed to raise after-tax profits have done nothing to reverse these trends.

To conservatives, the corporation is often treated as the pinnacle of capitalist development. This justifies their deferential treatment of corporations in terms of taxation and government regulation, which, they claim threaten to kill the goose that lays golden eggs.

In reality, the corporation wouldn’t exist in a pure free market. It is and always has been a creature of the state. For many years, corporate status was only granted to businesses deemed to be in the public interest, such as companies that built turnpikes and canals. But as time has gone by, the idea that corporations exist at the pleasure of the state and in the public interest has been forgotten.

Today, it is widely believed that corporations exist for the sole purpose of making a profit. Corporate executives who believe corporations have a social responsibility are considered old fashioned. But the costs of this new view of the corporation have been very high in terms of lost jobs and investment, and minuscule wage growth for more than a generation. Shareholders, the owners of the corporation, haven’t even benefitted that much from the laser-like focus on profit above all else because much of it has been siphoned off by corporate executives, who have enriched themselves at the expense of shareholders, and financial institutions that have encouraged companies to become highly leveraged.

Origins of the Corporation

Corporations have existed since Roman times. Until the Industrial Revolution, they tended to take the form of guilds, organizations of skilled laborers. The essential feature of these early corporations and guilds was their monopoly status. One had to belong to a guild or work for the corporation to engage in particular businesses. Well into the modern era, corporate charters were often granted by kings or parliaments to confer monopoly status on trade with particular countries.

Until the early part of the 19th century, the corporate form of business organization was rare. Most businesses were partnerships or sole proprietorships. Since most businesses were small, they did not need one of the corporation’s greatest benefits: the ability to raise capital through stock offerings, which was facilitated by the corporation’s longevity. The rise of the railroads, which required more private capital than had ever before been raised, was a key factor in the development of the modern corporation.

But the corporation remained a privileged institution that could only be obtained by legislative charter. Furthermore, corporations of the early 19th century, in both the United States and Britain, lacked an important characteristic of today’s corporations: limited liability. Because of that, a corporation’s liabilities may only be paid out of corporate assets; creditors and others with claims against a corporation may not go after the assets of shareholders, whose losses are limited to the value of their shares.

Limited liability became another privilege granted by the state to corporations, which greatly hastened their development. States also eased the requirements for obtaining corporate status. Instead of requiring a legislative charter, the creation of a corporation was simply rubber stamped by state officials.[1]

Well into the 20th century, the idea persisted that corporations were only permitted to exist and enjoy benefits unavailable to other forms of business, such as unlimited life and limited liability, because they served some sort of public purpose. Corporations commonly deferred to the interests of the communities in which they operated and other stakeholders, which was widely viewed as necessary to their legitimacy. In 1957, this was the common view of a corporation’s diverse constituencies and priorities:

No longer the agent of proprietorship seeking to maximize return on investment, management sees itself as responsible to stockholders, employees, customers, the general public, and, perhaps most important, the firm itself as an institution. To the customers, management owes an improving product, good service, and fair dealing….To the employees, management owes high wages, pensions and insurance systems, medical care programs, stable employment, agreeable working conditions, a humane personnel policy. Its responsibilities to the general public are widespread: leadership in local charitable enterprises, concern with factory architecture and landscaping, provision of support for higher education, and even research in pure science, to name a few.[2]

Shareholder Primacy

This all began to change in the 1970s. University of Chicago economist Milton Friedman fired the first salvo against the traditional view of corporate responsibility as being divided among various stakeholders. He said this is wrong; the corporation has only one responsibility: to the shareholder, who is the owner of the business. In Friedman’s view, “ownership” confers an almost absolute right to use whatever property is owned in whatever way the owner chooses, subject only to the constraints of law. Since the shareholder is the owner, he is entitled to 100 percent of the profit less taxes. Any benefits the corporation confers upon non-shareholders that aren’t for the ultimate purpose of profitability are, in essence, theft of money that belongs to the shareholder. Friedman believed that narrowing the focus of the corporation to the single goal of maximum profitability would improve productivity and efficiency, and thereby raise economic growth and improve wellbeing to the greatest extent that corporations in general could do so.[3]

In an extraordinarily influential article in 1976, University of Rochester economists Michael Jensen and William Meckling argued that shifting the focus of management solely toward the maximization of shareholder value offered a solution to the longstanding problem of ownership and control of the corporation.[4]

Since at least the 1930s, economists and legal scholars had been concerned about the fact that, in modern large corporations, the owners (i.e., the shareholders) had little control over the assets that they owned. As a practical matter, they were controlled by corporate management.[5] In theory, managers were simply employees working for the shareholders, who were represented by the corporation’s board of directors to look out for their interests. But in practice, boards did a poor job of representing shareholders. Being a board member was not a full-time job; boards might only meet a couple of times a year. Boards lacked the information necessary to really understand what the company was doing on a day-to-day basis and often merely ratified whatever the CEO was doing as long as he was doing reasonably well. And board members tended to be hand-picked by the CEO, making them effectively subservient to management.

The problem of ownership and control in a corporation has existed since the beginning. In 1776, Adam Smith defined it:

The directors of such companies, however, being the managers rather of other people’s money than of their own, it cannot well be expected that they should watch over it with the same anxious vigilance with which the partners in a private copartnery frequently watch over their own. Like the stewards of a rich man, they are apt to consider attention to small matters as not for their master’s honor, and very easily give themselves a dispensation from having it. Negligence and profusion, therefore, must always prevail, more or less, in the management of the affairs of such a company. It is upon this account that joint stock companies for foreign trade have seldom been able to maintain the competition against private adventurers. They have, accordingly, very seldom succeeded without an exclusive privilege, and frequently have not succeeded with one. Without an exclusive privilege they have commonly mismanaged the trade. With an exclusive privilege they have both mismanaged and confined it.[6]

Elimination of managerial discretion, as Friedman, Jensen and Meckling advocated, and forcing management to concentrate only on profitability would, they argued, align management’s objectives with the interests of shareholders in a way that could be measured by share prices and rates of return. To further align their interests, boards needed to adjust managerial compensation to be more dependent on profitability. Instead of simply paying them a salary like all the other employees, boards began granting stock options to senior management so that higher profits and share prices would translate directly into higher compensation.

Profits-Based Compensation

As with many ideas that look good on paper, encouraging management to put profits first and tying its compensation to near-term stock prices had serious downsides. It made management very short-term focused, often causing it to put the corporation’s long-term interest at risk, a point made as early as 1980 by Harvard Business School professors Robert Hayes and William Abernathy.[7] It also encouraged stock price manipulation through share buybacks. By 1986, management guru Peter Drucker was warning about the negative consequences of the profits-centric approach:

Corporate capitalism promised that large corporations would be run in the interests of a number of “stakeholders.” Instead, corporate managements are being pushed into subordinating everything (even such long-range considerations as a company’s market standing, its technology, indeed its basic wealth-producing capacity) to immediate earnings and next week’s stock price. A Marxist might well say that corporate capitalism has turned into “speculator’s capitalism.”[8]

The problem was exacerbated by 1993 legislation limiting the tax deductibility of managerial pay to $1 million per year; the idea being to put limits on managerial compensation. But, importantly, incentive pay, such as stock options, was exempted. This led corporate boards to make stock options an even larger component of executive compensation, making executives far richer in the process – a classic example of the law of unintended consequences.[9]

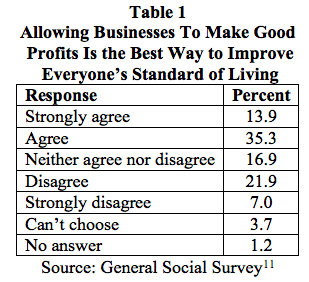

Nevertheless, by the mid-1990s, the idea that corporations should concern themselves solely with making as much profit as possible was so much the conventional wisdom that Bill Clinton could say in a radio address, “The most fundamental responsibility for any business is to make a profit.”[10] This view is shared by the public according to various surveys.

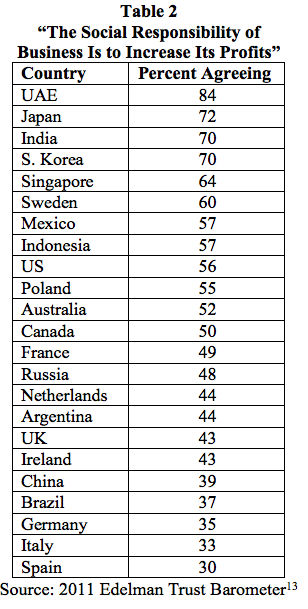

In the latest one available, 75 percent of people said the top priority of a corporation is to its shareholders. Only 22 percent said it is to the corporation’s employees.[12] In fact, according to an international survey, the Friedman idea is even more popular in socialist Sweden than it is in the U.S.

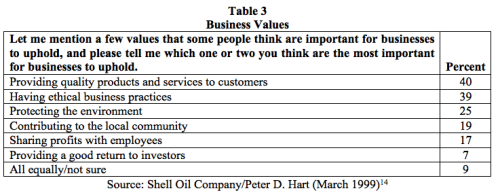

On the other hand, while the profit motive is supported, most people still rank other corporate objectives much more highly.

Backlash

Some former supporters of the shareholder value movement are now having second thoughts. Jack Welch, CEO of General Electric between 1981 and 2001, has called it a dumb idea. As he told the Financial Times in 2009, “On the face of it, shareholder value is the dumbest idea in the world. Shareholder value is a result, not a strategy….Your main constituencies are your employees, your customers and your products.”[15]

There is now a growing movement for reinstating the idea of corporate social responsibility and encouraging managers to get away from their single-minded pursuit of short-term profits.[16] But the Friedman approach is now deeply embedded in the psychology of markets and ingrained in a generation of managers. It also powerfully supports the political conservative view that concerns about the environment, diversity, inequality and others have no place in corporate or government policy.[17]

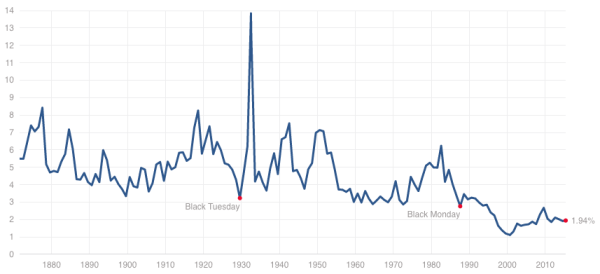

It used to be that the main reason people bought corporate stock was for the dividend yield; the hope for a rising share price was a secondary consideration. But as corporations focused more on generating profits to the exclusion of all else and managerial compensation increasingly took the form of stock options, the share price became the primary focus, with dividends falling in importance.[18] Share repurchases became a substitute for dividends.[19]

Managers rationalized that they were doing shareholders a favor. Dividends were taxed as ordinary income, whereas capital gains were taxed much more lightly. Moreover, capital gains taxes weren’t payable until shares were sold, while taxes on dividends had to be paid annually. Assuming a share repurchase raised share prices by the same amount as would be the case if the money was paid out as a cash dividend, taxable shareholders would prefer share buybacks. (The bulk of shares are owned by nontaxable pension funds.)

But there are problems. One is that managers can control the timing of share buybacks, which they use to pump up stock prices around the time their stock options are vested. Following is the summary of a recent study:

We show that CEOs strategically time corporate news releases to coincide with months in which their equity vests. These vesting months are determined by equity grants made several years prior, and thus unlikely driven by the current information environment. CEOs reallocate news into vesting months, and away from prior and subsequent months. They release 5 percent more discretionary news in vesting months than prior months, but there is no difference for non-discretionary news. These news releases lead to favorable media coverage, suggesting they are positive in tone. They also generate a temporary run-up in stock prices and market liquidity, potentially resulting from increased investor attention or reduced information asymmetry. The CEO takes advantage of these effects by cashing out shortly after the news releases.[20]

In effect, corporate executives manipulate stock prices for their own benefit. Indeed, for many years, corporations were restricted by the Securities and Exchange Commission from using profits to buy back shares precisely because it could too easily be done to manipulate stock prices. But the SEC changed its policy in 1982. Federal Reserve Board chairman Alan Greenspan explained the significance in a 2002 speech.

Prior to the past several decades, earnings forecasts were not nearly so important a factor in assessing the value of corporations. In fact, I do not recall price-to-earnings ratios as a prominent statistic in the 1950s. Instead, investors tended to value stocks on the basis of their dividend yields. Since the early 1980s, however, corporations increasingly have been paying out cash to shareholders in the form of share repurchases rather than dividends. The marginal individual tax rate on dividends, with rare exceptions, has always been higher than the marginal tax rate on capital gains that repurchases create by raising per share earnings through share reduction. But, until the early 1980s, share repurchases were frowned upon by the Securities and Exchange Commission, and companies that repurchased shares took the risk of being investigated for price manipulation.

In 1982, the SEC gave companies a safe harbor to conduct share repurchases without risk of investigation. This action prompted a marked shift toward repurchases in lieu of dividends to avail shareholders of a lower tax rate on their cash receipts. More recently, a desire to manage shareholder dilution from the rising incidence of employee stock options has also spurred repurchases.

As a consequence, dividend payout ratios, which in decades past averaged about 55 percent, have in recent years fallen on average to about 35 percent. But because share prices have risen so much more than earnings in recent years, dividend yields — the ratio of dividends per share to a company’s share price – have fallen appreciably more than the payout ratio. A half-century ago, for example, dividend yields on stocks typically averaged 6 percent. Today such yields are barely above 1 percent.

The sharp fall in dividend payout ratios and yields has dramatically shifted the focus of stock price evaluation toward earnings. Unlike cash dividends, whose value is unambiguous, there is no unambiguously “correct” value of earnings.[21]

In 2014, 95 percent of the profits of the S&P 500 companies went into share buybacks.[22] The dividend yield remains very low by historical standards. In the early 1950s, it was over 6 percent; lately it’s been under 2 percent.

Figure 1

S&P 500 Dividend Yield

Source: http://www.multpl.com/s-p-500-dividend-yield/

But shareholders don’t benefit as much as it might appear because shares are constantly being diluted by stock options granted to corporate executives, which were given a tax preference in 1981.[23] The net benefit to shareholders is much less since much of the share buybacks simply offsets the dilution. Financial analyst Will Becker explains another problem:

Buybacks are typically initiated in good times when stock prices are high…. Corporations end up purchasing their own stock at inflated prices, only to have many of these same shares then redeemed by management as compensation committees increasingly hand out these perks in good times.[24]

When an employee exercises her stock options, the company issues new stock to cover them. Thus stock options inherently dilute the shares of existing shareholders, making them worth less. When corporate profits are used for stock buybacks, shares are taken out of the market and held by the corporation; thus the number of shares outstanding falls and makes each remaining share worth more. If a company issues $100 million in stock options and buys back $100 million worth of shares, it is a wash; existing shareholders have not benefitted. If the company buys back $150 million in shares, only $50 million of the buyback really benefits shareholders.

Because stock options don’t involve a direct cash outlay, as is the case with wages, shareholders tend to view them as cheaper than salaries, when in fact they are extremely costly from the point of view of the shareholder, coming directly at their expense.[25] For this reason, many economists believe it would be better from the shareholder’s point of view if companies abandoned buybacks and went back to issuing dividends. The need to pay dividends and avoid reducing the yield tends to discipline corporate executives to manage for the long term.

Economic Cost of Share Buybacks

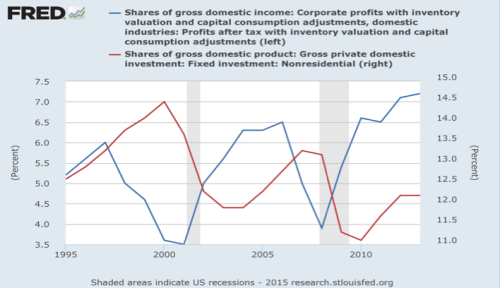

Disturbingly, there is growing evidence that share buybacks come at the expense of long-term profitability and the economy as a whole, because they lead managers to reduce or postpone investment spending for new projects, research and development, advertising and maintenance in order to meet near-term earnings targets. In other words, managers are literally destroying shareholder value as a routine way of doing business.[26] This helps explain why nonresidential fixed investment has fallen as profitability has risen.

Figure 2

Profits Come at the Expense of Investment

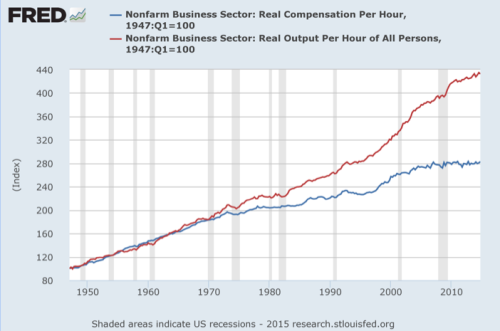

The demand for profitability has also undoubtedly contributed to job losses in the United States as companies turned to outsourcing to reduce costs and raise profits. Moreover, it has also caused them to take a much harder line against unions and to squeeze worker pay relentlessly, again to cut costs and raise profits, regardless of the human or social consequences. This is one reason why the percentage of employed workers who are members of labor unions has fallen from 18.8 percent in 1984 to just 11.3 percent in 2013. And worker pay, which rose with productivity for generations, has been flat since 2007 despite rising productivity. Output gains that once went largely to workers now pad corporate profits instead.[27] Labor compensation’s share of GDP, which was about two-thirds for decades, has fallen to about 62 percent.[28]

Figure 3

Real Compensation Per Hour and Real Output Per Hour

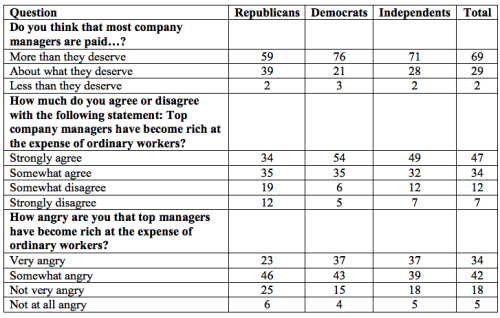

Consequently, even a solid majority of Republicans now believe that corporate executives are overpaid and that their gains have come at the expense of ordinary workers.

Table 4

Opinions About Corporate Managers’ Compensation (percent)

Source: Harris Poll[29]

Short-Term Focus

It has also been argued that the excessive short-term focus of corporate strategy blinded managers to signs of economic imbalances that ultimately led to the longest and deepest recession in postwar history. For instance, in July 2007, the CEO of Citigroup defended his bank’s generous lending policy despite signs of a housing bubble, saying, “When the music stops, in terms of liquidity, things will be complicated. But as long as the music is playing, you’ve got to get up and dance. We’re still dancing.”[30] This attitude is evidence that the focus on near-term profitability blinded corporate executive to actions they were taking that proved extremely costly to their companies and the economy in the longer run.[31]

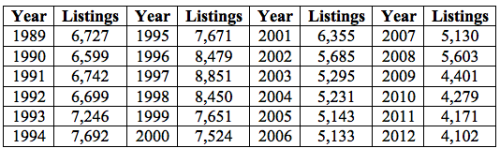

Some of the long-term effects of the profit-centric approach to corporate management are not yet apparent, but could be problems down the road. One is that as a result of share buybacks, corporate takeovers and mergers, and the effects of the financial crisis, the number of publicly-traded corporations listed on U.S. stock exchanges has fallen dramatically.

Table 5

Listings On U.S. Stock Exchanges

Source: Standard & Poor’s[32]

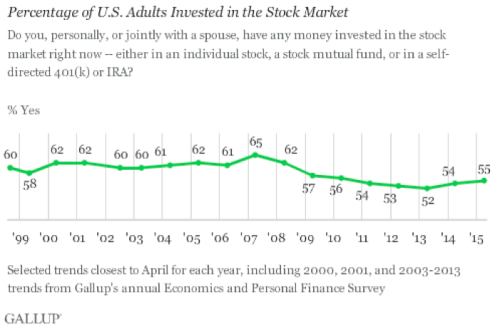

Concomitantly, fewer Americans own shares of corporate stock, either outright or through a mutual fund. According to Gallup, the percentage of adults (personally or with a spouse) having money invested in the stock market – either in individual stocks, an Individual Retirement Account, mutual fund or 401(k) account – fell from 65 percent in 2007 to 55 percent in 2015.[33]

Figure 4

While we don’t yet know the consequences of this profound change in business ownership, its narrowing may tend to insulate corporate management further from market forces, the opposite of what Friedman intended.[34] As George W. Bush once put it, “If you own something, you have a vital stake in the future of our country. The more ownership there is in America, the more vitality there is in America, and the more people have a vital stake in the future of this country.”[35] But if fewer Americans own corporate stock and there are fewer corporations with stock to own, then a vital link between the public and the corporate community may be lost, with potential implications for corporate legitimacy, tax policy and government regulation.

The obsession with corporate profits was, arguably, a major cause of the economic crisis. Both investors and professional analysts were deluded into ignoring any indicator of corporate performance other than the share price, which was assumed to simply equal the discounted value of future earnings, whether paid out as dividends or share buybacks. It was also assumed that all information affecting share prices was instantly incorporated into those prices via something called the efficient market hypothesis.

Dow 36,000

In the 1990s, political conservatives such as James Glassman, Kevin Hassett and Charles Kadlec were quick to embrace the profit-centric focus of the corporation as a way that the average person could get rich quick. Glassman and Hassett wrote an infamous book called “Dow 36,000” in late 1999, just before the stock market peaked in early 2000.[36] Kadlec was even more optimistic in a book that appeared almost simultaneously, “Dow 100,000,” which the author predicted would be reached by the year 2020. The latter book even carried the imprimatur of the New York Institute of Finance.[37] Tellingly, the dust jacket for “Dow 100,000” carried the endorsements of leading conservatives:

- Steve Forbes: “I think Dow 100,000 may be prophetic.”

- Art Laffer: “This book is a must-read. I wish I had written it.”

- Jack Kemp: “Every policymaker, investor, and entrepreneur should read Dow 100,000 to see the vital link between good economic policy, long-term growth, and prosperity.”

Glassman and Hassett were associated with the right-wing American Enterprise Institute in Washington. Their book, too, received high praise from political conservatives. The dust jacket quotes economist Allan Meltzer saying, “Every stock owner should read this book.” David Malpass,[38] then chief economist for Bear Stearns, said:

Either we are in a bubble with inefficient financial markets, or else past theories on stock prices and price-earnings multiples have to be revised. In every one of my meetings with mutual funds these days, I have to address the issue of whether stocks are overvalued. Glassman and Hassett’s theories make the solid case that, on average, they are not.

Reputable stock analysts, however, immediately threw cold water on the Glassman-Hassett theory as soon as their basic analysis was published in a Wall Street Journal op-ed article in 1998.[39] Wharton School economist Jeremy Siegel, whose research underlay the book, said “their analysis contains a serious flaw which vastly overstates the value of stocks.” In effect, they double-counted corporate profits and corporate investment, he said.[40] When the book was published, economist Burton Malkiel of Princeton reviewed it and said the authors had conflated earnings and cash flow. Said Malkiel, “I believe ‘Dow 36,000’ is a dangerous book that may lead some investors who can ill afford the significant risks of equity investments to throw caution to the wind.”[41]

The month “Dow 36,000” was published, in September 1999, the Dow Jones Industrial average was about 11,000. It didn’t go much higher before beginning a steep fall in early 2000 that took it down to just over 7,000. Even with the sharp run-up in the stock market in 2010s, the DJIA is still less than half of 36,000. But neither Glassman nor Hassett suffered for their gross incompetence. The former went on to become an under secretary of State and was the founding executive director of the George W. Bush Institute, while the latter is director of economic policy studies at AEI. Glassman continues to assert that he was right, despite all the evidence to the contrary.[42]

One reason conservatives were so quick to endorse a theory that, in hindsight, was complete nonsense is that it justified corporate actions that led to mass layoffs, outsourcing, deunionization, unrelenting downward pressure on wages, downsizing of benefits, automation and other actions corporations have taken in recent years to raise earnings. In effect, what Glassman, Hassett and Kadlec were saying to the average guy is that he can easily compensate for the loss of jobs and income simply by getting on the bandwagon of share ownership. If she bought stocks, her capital income would replace the lost wages and benefits.

Workers Into Capitalists

It has long been a conservative goal to turn workers into capitalists. While seemingly unobjectionable – indeed, worker ownership of the means of production originated as a policy of the far left called syndicalism – the clear political goal of the right has been to align the interests of workers with those of investors and managers, and in the process encourage them to support free market policies, tax cuts for capital, maximum profits and, of course, the Republican Party.[43]

As a study by the libertarian Cato Institute concluded: “Broadly stated, our findings show that as wage earners become owners of capital, they favor policies that reduce taxes on savings, investment, and capital gains.”[44] Republican operative Grover Norquist was even more explicit:

When a wage worker enters the investor class through a work-based 401(k), his opinions on vouchers, free trade, and entitlement privatization are no likelier to change overnight than his party affiliation. But as his plan assets grow, so do his expectations for their performance. He may at first study nothing more than the plan materials his employer provides. But over time, he actively seeks sources of information that will maximize his efficiency in his new vocation: that of a capitalist. It is this pursuit that changes his opinions on a variety of partisan and policy questions to favor market-based solutions and their political advocates.[45]

This was certainly Ronald Reagan’s goal in establishing a task force chaired by ultra-conservative investor J. William Middendorf to study worker-controlled companies in developing countries to fend off communism. When workers have a stake in the place where they work, Reagan said, they have “a stake in the freedom of their country.” In the U.S., employee ownership is “a path that benefits a free people.”[46]

In the 1970s, the conservative chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, Senator Russell Long of Louisiana, became enamored with Employee Stock Ownership Plans (ESOPs) and he created and expanded tax incentives for them.[47] But rather than making rich capitalists of workers, ESOPs found their greatest success as a managerial technique for fending off corporate raiders, often at the expense of shareholders.[48] Sometimes workers lost their life savings when the companies their ESOPs were invested in, such as Enron, collapsed.[49] On balance, it is doubtful that workers have benefitted much from ESOPs. One problem is that they are required to be invested only in company stock, thus preventing workers from receiving the benefits of diversification.[50]

Under George W. Bush, Republicans were aggressive in pushing share ownership, believing that those who owned corporate stock would be more likely to vote Republican. During the 2000 campaign, Bush endorsed private accounts for Social Security, saying, “Ownership in our society should not be an exclusive club. Independence should not be a gated community. Everyone should be a part-owner in the American Dream.”[51] Republicans are more likely to invest in stocks. They also have a much higher opinion of corporations generally than independents or Democrats.[52]

Table 6

Views of the Stock Market, 2005

| How confident are you in your ability to make good investment decisions in the stock market? | Republicans | Democrats | Independent |

| Very confident | 24 | 8 | 10 |

| Somewhat confident | 42 | 31 | 31 |

| Not very confident | 15 | 32 | 30 |

| Not confident at all | 18 | 28 | 27 |

| Do you think of investment in the stock market as generally a safe investment or generally a risky investment? | |||

| Safe | 36 | 11 | 19 |

| Risk | 56 | 84 | 78 |

| Unsure | 8 | 5 | 3 |

| Do you personally, or jointly with a spouse, have any money invested in the stock market right now ‑‑ either in individual stock or in a mutual fund –or don’t you? | |||

| Do | 59 | 40 | 43 |

| Do not | 40 | 60 | 55 |

| Unsure | 1 | 1 | 2 |

Source: CBS News/New York Times poll (June 10-15, 2005)[53]

A recent sociological study confirmed the relationship:

Our findings suggest that stock ownership may have a causal relation with perceptions of political interest. Even our very crude measure of stockholding shows consistent positive effects on Republicanism in cross-sectional models, and the size of the effect increased substantially as Republican policy initiatives came to follow the prescriptions of the investor class theorists (cutting taxes on capital gains and dividends; proposing to privatize Social Security).[54]

An economic study also found a correlation: “We use mutual fund cost data to proxy for stock ownership and find evidence supporting the hypothesis that an investor class effect has increased the Republican share of the House popular vote.”[55]

George W. Bush pushed hard for Social Security privatization, which would have been a boon to Wall Street money managers, and big tax breaks for owners of corporate stock. Both were premised on a desire to bolster the investor class in order to increase the ranks of Republican voters.

Bush Tax Cut Failure

The 2003 tax cut was especially aimed at investors. Its principal provision was a sharp reduction in the tax rate on dividends to the same low rate that applied to capital gains. Bush defended this action as designed to increase dividend payments:

This will encourage more companies to pay dividends, which in itself will not only be good for investors but will be a corporate reform measure. It’s hard to pay dividends unless you’ve actually got cash flow. The days when people could say, “Invest with me because the sky’s the limit,” will be changed by dividend policy. It’s hard to promote the sky being the limit and pay dividends unless you’re actually profitable and have cash flow. Getting – reducing the tax rate on dividends will also increase the wealth effect around America and will help our markets.[56]

The impact on economic growth was always dubious. Former Nixon aide Kevin Phillips was incredulous. The tax cut is “not aimed at the little investor. It’s aimed at the big investor and shrouded by a fog of phoniness. This isn’t even trickle-down economics. It’s mist-down economics,” he said.[57]

In the end, the Bush tax cuts neither stimulated the economy nor raised dividend payments, as it was expressly designed to do. A number of academic studies document this fact.

- A survey of financial executives found a modest increase in dividend payments that was mainly driven by improved cash flow, rather than tax effects. There was, in fact, a much larger increase in share repurchases even though their tax treatment was unchanged.[58]

- A 2008 study found no impact of the Bush tax cuts on the aggregate stock market. U.S. stocks didn’t outperform foreign stocks or those unaffected by the dividend tax cuts, such as Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs). Stocks paying no dividends enjoyed excess returns during the study period, suggesting that non-tax forces were driving the stock market.[59]

- A 2011 study found that because the dividend tax cut was temporary – all the Bush tax cuts were scheduled to expire at the end of 2010 because of the budget rules necessary to get them enacted – they actually caused aggregate investment to fall.[60] A more recent study found zero change in investment.[61]

- A 2013 study found that the payout ratio did not rise after the 2003 tax cut, share repurchases rose more rapidly than dividend payouts, dividend payouts by REITs increased even though they did not qualify for lower taxes, and what increase in dividends did take place was consistent with estimates made in 2002, before the tax cut was even contemplated.[62]

In 2010 and 2012, the Congressional Research Service studied the potential effect of allowing all the Bush tax cuts to expire on schedule. (They were extended for two years in late 2010.) It found that there was unlikely to be any major negative impact on the economy because the tax cuts had no positive effect in the first place. In fact, the economy performed more poorly following the Bush tax cuts than it did in the higher-tax era of the 1990s following the 1993 tax increase.[63] The CRS produced the following table as evidence.

Table 7

Economic Indicators Before and After the Tax Cuts for Expansion Years

(annual average)

| Indicator | 1993-2000 | 2003-2007 |

| GDP Growth | 3.9% | 2.7% |

| Median Real Household Income Growth | 1.7% | 0.6% |

| Private Employment Growth | 2.7% | 1.2% |

| Weekly Hours Worked | 34.4 | 33.8 |

| Employment-Population Ratio | 63.4% | 62.7% |

| Unemployment Rate | 5.2% | 5.2% |

| Personal Savings as % of Disposable Income | 4.6% | 2.6% |

| Business Investment Growth | 10.3% | 5.6% |

| Labor Productivity Growth | 2.0% | 2.2% |

Source: Congressional Research Service

Even though the stock market began crashing on Bush’s watch, Republican mouthpieces like economist Michael Boskin nevertheless blamed its weakness in early 2009 entirely on Obama’s policies.[64] But the stock market performed far better under Obama than it did under Bush.

Figure 5

When the stock market was far lower than it is today, right-wing economist Larry Kudlow said, “I have long believed that stock markets are the best barometer of the health, wealth and security of a nation. And today’s stock market message is an unmistakable vote of confidence for the president.”[65] I have never heard him praise President Obama similarly as the stock market hit new high after new high – after the Bush tax cuts expired. At least one analyst accurately foresaw the positive impact of higher taxes on the stock market, writing on January 8, 2013: “I’m not prepared to predict that the great bull market of the 2010s began on Jan. 2. But I do know that anyone who thinks tax increases never precede a bull market is wrong. History proves that.”[66] Those who bought gold didn’t do as well.

Once Bush was gone from office, Republican economists who either supported his tax cuts or kept silent about their defects suddenly saw nothing good in them. Douglas Holtz-Eakin, a former CBO director who now runs a Republican think tank, said, “There was very little of the kind of saving and export-led growth that would be more sustainable. For a group that claims it wants to be judged by history, there is no evidence on the economic policy front that that was the view. It was all Band-Aids.”[67]

Harvard economist Dale Jorgenson, a Republican, was asked what positive features he saw in the Bush tax cuts. He replied, “I don’t see any redeeming features, unfortunately.”[68]

American Enterprise Institute economist Alan Viard said, “The effects of the Bush tax cuts on growth were ambiguous at best. They were not much of a poster child for pro-growth tax policy.”[69]

Even the Columbia University economist Glenn Hubbard, who essentially designed the tax cuts as chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers for Bush, saw little value in them by 2013. He told the New York Times that many provisions were no longer needed. The 2001 and 2003 tax cuts “are not the best anchoring point” for debate on the future of tax policy, he said. “We need a tax system that can promote economic growth and raise the revenue the American people want to devote to government,” Hubbard added, suggesting the need for higher revenues.[70]

So obvious was the failure of the Bush tax cuts by 2012 that the Mercatus Center, a right-wing think tank on whose board the billionaire Charles Koch sits, published a study trying to explain what went wrong. It claimed that the tax cuts did not in fact represent free market policy – they were phased-in slowly, were enacted with a 10-year expiration date, and were designed more to stimulate consumption than investment.[71] The study also complained that Bush was a big-spender. When I made exactly the same arguments in a 2006 book, I was fired from a conservative think tank and excommunicated from the conservative movement.[72]

In the end, the main effects of the Bush tax cuts were to massively increase the national debt and worsen the distribution of income.[73]

Conclusion

Shareholder primacy was supposed to align the interests of corporate owners and managers, improve efficiency and economic growth. It has done none of those things. All it has done is enrich corporate executives, while impoverishing workers and the communities in which corporations operate. Consequently, there is a growing back lash against shareholder primacy and an effort to reinstate social responsibility as a managerial doctrine.[74] But it may be impossible to put the toothpaste back in the tube.

[1] On the history of the corporation as a creature of the state, see Oscar Handlin and Mary F. Handlin, “Origins of the American Business Corporation,” Journal of Economic History, 5:1 (May 1945): 1-23; Shaw Livermore, “Unlimited Liability in Early American Corporations,” Journal of Political Economy, 43:5 (October 1935): 674-87; H.A. Shannon, “The Coming of General Limited Liability,” in Essays in Economic History, Vol. 1, ed. E.M. Carus-Wilson (London: Edward Arnold, 1954): 358-79; William Letwin, Law and Economic Policy in America (NY: Random House, 1965): 62-67; Ronald E. Seavoy, “The Public Service Origins of the American Business Corporation,” Business History Review, 52:1 (Spring 1978): 30-60; Paddy Ireland, “Limited Liability, Shareholder Rights and the Problem of Corporate Irresponsibility,” Cambridge Journal of Economics, 34:5 (September 2010): 837-56.

[2] Carl Kaysen, “The Social Significance of the Modern Corporation,” American Economic Review, 47:2 (May 1957): 313.

[3] Milton Friedman, “The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits,” New York Times Magazine (September 13, 1970).

[4] Michael C. Jensen and William H. Meckling, “Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure,” Journal of Financial Economics, 3:4 (October 1976): 305-60. It has been argued that the popularity of the shareholder primacy approach owed much to the unique economic conditions of the early 1970s because the stock market was widely viewed as under-valued. See Lynn A. Stout, “The Toxic Side Effects of Shareholder Primacy,” University of Pennsylvania Law Review, 161:7 (June 2013): 2003-23.

[5] The classic work is Adolf A Berle and Gardiner C. Means, The Corporation and Private Property (NY: Macmillan, 1936).

[6] Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations (NY: Modern Library, 1937): 700.

[7] Robert H. Hayes and William J. Abernathy, “Managing Our Way to Economic Decline,” Harvard Business Review, 58:4 (July/August 1980): 67-77.

[8] Peter F. Drucker, “A Crisis of Capitalism,” Wall Street Journal (September 30, 1986): 32.

[9] Kenneth R. Ferris and James S. Wallace, “IRC Section 162(m) and the Law of Unintended Consequences,” Advances in Accounting, 25:2 (December 2009): 147-55.

[10] William J. Clinton, “The President’s Radio Address,” The White House (March 23, 1996).

[11]http://www3.norc.org/gss+website/. Question asked 1983-96.

[12] “Is the American Dream Still Attainable?” McClatchy-Marist Poll (February 14, 2014).

[13]http://www.slideshare.net/EdelmanInsights/2011-edelman-trust-barometer.

[14] Accessed at PollingReport.com.

[15] Francesco Guerrera, “Welch Denounces Corporate Obsessions,” Financial Times (March 13, 2009).

[16] Donald S. Siegel and Donald F. Vitaliano, “An Empirical Analysis of the Strategic Use of Corporate Social Responsibility,” Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 16:3 (Fall 2007): 773-92; Archie B. Carroll and Kareem M. Shabana, “The Business Case for Corporate Social Responsibility: A Review of Concepts, Research and Practice,” International Journal of Management Reviews, 12:1 (March 2010): 85-105; Herman Aquinis and Ante Glavas, “What We Know and Don’t Know About Corporate Social Responsibility: A Review and Research Agenda,” Journal of Management, 38:4 (July 2012): 932-68.

[17] In fact, libertarian theory doesn’t really support the way in which Friedman’s view has become embedded in corporate governance. See Richard Nunan, “The Libertarian Conception of Corporate Property: A Critique of Milton Friedman’s Views on the Social Responsibility of Business,” Journal of Business Ethics, 7:12 (December 1988): 891-906; Thomas Mulligan, “A Critique of Milton Friedman’s Essay, ‘The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits,’” Journal of Business Ethics, 5:4 (August 1986): 265-69; Denis G. Arnold, “Libertarian Theories of the Corporation and Global Capitalism,” Journal of Business Ethics, 48:2 (December 2003): 155-73

[18] Eugene Fama and Kenneth R. French, “Disappearing Dividends: Changing Firm Characteristics or Lower Propensity to Pay?” Journal of Financial Economics, 60:1 (April 2001): 3-43.

[19] Gustavo Grullon and Roni Michaely, “Dividends, Share Repurchases, and the Substitution Hypothesis,” Journal of Finance, 57:4 (August 2002): 1649-84.

[20] Alex Edmans et al., “Strategic News Releases in Equity Vesting Months,” NBER Working Paper No. 20476 (September 2014).

[21] Alan Greenspan, “Corporate Governance,” Federal Reserve Board (March 26, 2002).

[22] “S&P 500 Companies Spend Almost All Profits on Buybacks,” Bloomberg News (October 6, 2014).

[23] Michael W. Melton, “The Alchemy of Incentive Stock Options – Turning Employee Income Into Gold,” Cornell Law Review, 68:4 (April 1983): 488-520.

[24] Quoted in Chris Matthews, “Will 2015 Mark the End of the Great Stock Buyback Binge?” Fortune (February 11, 2015).

[25] Brian J. Hall and Kevin J. Murphy, “The Trouble With Stock Options,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 17:3 (Summer 2003): 49-70.

[26] William Lazonick, “Profits Without Prosperity,” Harvard Business Review, 92:9 (September 2014): 46-55; John R. Graham, Campbell R. Harvey, and Shiva Rajgopal, “Value Destruction and Financial Reporting Decisions,” Financial Analysts Journal, 62:6 (November-December 2006): 27-39; Sugata Roychowdhury, “Earnings Management Through Real Activities Manipulation,” Journal of Accounting & Economics, 42:3 (December 2006): 335-70.

[27] Tim Catts, Peter Robison and Ilan Kolet, “Wages Stagnate as U.S. Manufacturers Reap Record Profits,” Bloomberg News (November 21, 2013).

[28] Michael W.L. Elsby, Bart Hobijn and Ayşegül Şahin, “The Decline of the U.S. Labor Share,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity (Fall 2013): 1-52.

[29] “Large Majorities of Americans Believe Top Managers Make More Than They Deserve,” Harris Poll (November 11, 2011).

[30] Quoted in Michiyo Nakamoto and David Wighton, “Citigroup Chief Stays Bullish on Buy-outs,” Financial Times (July 9, 2007).

[31] Lynne L. Dallas, “Short-Termism, the Financial Crisis, and Corporate Governance,” Journal of Corporation Law, 37:2 (Winter 2012): 264-363.

[32] Accessed via the World Bank at http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/CM.MKT.LDOM.NO.

[33] Justin McCarthy, “Little Change in Percentage of Americans Who Own Stocks,” Gallup Poll (April 22, 2015).

[34] Gerald F. Davis, “The Twilights of the Berle and Means Corporation,” Seattle University Law Review, 34:4 (2011): 1121-38.

[35] George W. Bush, “Remarks to the National Federation of Businesses,” The White House (June 17, 2004).

[36] James K. Glassman and Kevin A. Hassett, Dow 36,000: The New Strategy for Profiting from the Coming Rise in the Stock Market (NY: Random House, 1999).

[37] Charles W. Kadlec, Dow 100,000: Fact or Fiction (NY: New York Institute of Finance, 1999).

[38] Malpass ran for the Republican nomination for the U.S. Senate from New York in 2010. Bear Stearns went out of business in 2008.

[39] James K. Glassman and Kevin A. Hassett, “Are Stocks Overvalued? Not a Chance,” Wall Street Journal (March 30, 1998).

[40] Jeremy J. Siegel, “Stocks Underpriced? Well, Not Quite,” Wall Street Journal (April 14, 1998). See also Jonathan Clements, “Throwing Cold Water on Dow 36,000,” Wall Street Journal (September 21, 1999).

[41] Burton G. Malkiel, “How Much Higher Can the Market Go?” Wall Street Journal (September 22, 1999).

[42] James K. Glassman, “Market Record Shows How to Get to Dow 36,000,” Bloomberg View (March 7, 2013). He was ridiculed in the same paper where he previously wrote a column: Neil Irwin, “Author of the Spectacularly Wrong ‘Dow 36,000′ Has New Thoughts on the Stock Market,” Washington Post (March 8, 2013).

[43] On the theory and history of worker control of businesses, see Gregory K. Dow, Governing the Firm: Workers’ Control in Theory and Practice (NY: Cambridge University Press, 2003).

[44] Richard Nadler, “The Rise of Worker Capitalism,” Cato Institute (November 1, 1999): 24.

[45] Quoted in Richard Nadler, “Portfolio Politics: Nudging the Investor Class,” National Review (December 4, 2000): 38-41.

[46] Ronald Reagan, “Remarks on Receiving the Report of the Presidential Task Force on Project Economic Justice,” The White House (August 3, 1987). See also Presidential Task Force on Project Economic Justice, High Road to Economic Justice (October 1986).

[47] Todd S. Snyder, “Employee Stock Ownership Plans (ESOPs): Legislative History,” CRS Report for Congress (May 2003).

[48] Susan Chaplinsky and Greg Niehaus, “The Role of ESOPs in Takeover Contests,” Journal of Finance, 49:4 (September 1994): 1451-70.

[49] David Millon, “Enron and the Dark Side of Worker Ownership,” Seattle Journal for Social Justice, 1:1 (2002): 113-26.

[50] Sean Anderson, “Risky Retirement Business: How ESOPs Harm the Workers They Are Supposed to Help,” Loyola University Chicago Law Journal, 41:1 (Fall 2009): 1-37.

[51] “George W. Bush on Social Security,” PBS Newshour (May 15, 2000).

[52] Frank Newport, “Americans Similarly Dissatisfied With Corporations, Gov’t,” Gallup Poll (January 17, 2013).

[53] Accessed at PollingReport.com.

[54] Gerald F. Davis and Natalie C. Cotton, “Political Consequences of Financial Market Expansion: Does Buying a Mutual Fund Turn You Republican?” University of Michigan (August 2007).

[55] John V. Duca and Jason L. Saving, “Stock Ownership and Congressional Elections: The Political Economy of the Mutual Fund Revolution,” Economic Inquiry, 46:3 (July 2008): 474.

[56] George W. Bush, “Remarks on Signing the Jobs and Growth Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2003,” The White House (May 28, 2003). The “wealth effect” refers to the idea that if household wealth increases, then people will spend 5 percent to 10 percent of the increase annually on goods and services. However, research has consistently shown that increases in financial wealth have a modest effect on aggregate spending because few average people own stock directly and most of that is in retirement accounts such as 401(k)s. The rich, who are much more likely to own stock, tend not to increase their spending much in response to a wealth increase. See Karl E. Case, John M. Quigley and Robert J. Shiller, “Wealth Effects Revisited: 1975-2012,” NBER Working Paper No. 18667 (January 2013).

[57] Quoted in Richard W. Stevenson, “The Politics of Portfolios,” New York Times (January 7, 2003).

[58] Alon Brav et al., “Managerial Response to the May 2003 Dividend Tax Cut,” Financial Management, 37:4 (Winter 2008): 611-24; Alon Brav et al., “The Effect of the May 2003 Dividend Tax Cut on Corporate Dividend Policy: Empirical and Survey Evidence,” National Tax Journal, 61:3 (September 2008): 381-96.

[59] Gene Amromin, Paul Harrison and Steven Sharpe, “How Did the 2003 Dividend Tax Cut Affect Stock Prices?” Financial Management, 37:4 (Winter 2008): 625-46.

[60] François Gourio and Jianjun Miao, “Transitional Dynamics of Dividend and Capital Gains Tax Cuts,” Review of Economic Dynamics, 14:2 (April 2011): 368-83.

[61] Danny Yagan, “Capital Tax Reform and the Real Economy: The Effects of the 2003 Dividend Tax Cut,” NBER Working Paper No. 21003 (March 2015).

[62]Jesse Edgerton, “Four Facts About Dividend Payouts and the 2003 Tax Cut,” International Tax and Public Finance, 20:5 (October 2013): 769-84.

[63] Marc Labonte, “What Effects Would the Expiration of the 2001 and 2003 Tax Cuts Have on the Economy?” CRS Report for Congress R41442 (December 21, 2010); Thomas L. Hungerford, “The 2001 and 2003 Bush Tax Cuts and Deficit Reduction,” CRS Report for Congress R42020 (July 18, 2012).

[64] Michael J. Boskin, “Obama’s Radicalism Is Killing the Dow,” Wall Street Journal (March 6, 2009).

[65] Lawrence Kudlow, “A Stock Market Vote of Confidence for Bush,” Real Clear Politics (July 20, 2007).

[66] Bruce Bartlett, “Tax Increases and Bull Markets,” Economix blog, New York Times (January 8, 2013).

[67] Quoted in Neil Irwin and Dan Eggen, “Economy Made Few Gains in Bush Years,” Washington Post (January 12, 2009).

[68] Quoted in David Leonhardt, “Partisan Economics in Action,” New York Times (October 7, 2009).

[69] Quoted in David J. Lynch, “Raising Taxes Isn’t a ‘Kiss of Death’ for Employment Growth, History Shows,” Bloomberg News (June 2, 2011).

[70] Quoted in Jonathan Weisman, “Lines of Resistance,” New York Times (January 2, 2013).

[71] Matthew Mitchell and Andrea Castillo, “What Went Wrong with the Bush Tax Cuts,” Mercatus Center (November 28, 2012). Academic studies have found that the phase-in of the Bush tax cuts did indeed blunt their stimulative effect. See Christopher L. House and Matthew D. Shapiro, “Phased-In Tax Cuts and Economic Activity,” American Economic Review, 96:5 (December 2006): 1835-49.

[72] Bruce Bartlett, Impostor: How George W. Bush Bankrupted America and Betrayed the Reagan Legacy (NY: Doubleday, 2006).

[73] Thomas L. Hungerford, “The Bush Tax Cuts and the Economy,” CRS Report for Congress R41393 (December 10, 2010); Karen C. Burke and Grayson M.P. McCouch, “Turning Slogans into Tax Policy,” Virginia Tax Review, 27:4 (2008): 747-81.

[74] Recent comments include Rex Nutting, “How the Stock Market Destroyed the Middle Class,” MarketWatch (April 24, 2015); Barry Ritholz, “Executive Pay Gluttony,” Bloomberg View (April 30, 2015); Rebecca Henderson and Karthik Ramanna, “Do Managers Have a Role to Play in Sustaining the Institutions of Capitali9sm?” Brookings Institution (February 9, 2015).

I was going to post this in Wednesday’s reads but Bartlett’s article thread seems a better fit. Reflecting on basic assumptions (and the kinds of questions they allow) often isn’t easy but it is unquestionably essential to critical thought.

The Rules are What Matter for Inequality

…inequality is not inevitable: it is a choice that we’ve made with the rules that structure our economy. Over the past 35 years, the rules, or the regulatory, legal and institutional frameworks, that make up the economy and condition the market have changed. These rules are a major driver of the income distribution we see, including runaway top incomes and weak or precarious income growth for most others. Crucially, however, these changes in the rules have not made our economy better off than we would be otherwise; in many cases we are weaker for these changes. We also now know that “deregulation” is, in fact, “reregulation” [emphasis mine]—that is, a new set of rules for governing the economy that favor a specific set of actors, …

This report describes what has happened …It also has a policy agenda focused on both taming the top and growing the rest of the economy. ….

I think the Supreme Court has been making it even simpler than this. They have come up with several rulings in the past decade where they are ascribing rights to corporations that were formerly just associated with people (e.g. freedom of speech (Citizens United), freedom of religion (Hobby Lobby)).

So along with rights come responsibilities. Many of the groups that are espousing shareholder value and low corporate taxes are also associated with groups that want to dictate how people should live their lives in their homes as well as pushing for criminalizing much individual behavior, such as recreational drug use. It is becoming ironic that corporations may now may be getting more freedom rights than individuals.

So if corporations really are getting close to actual personhood, then they should start behaving as upstanding citizens of the country enhancing “family values” by providing living wages, following laws etc. Making a profit should not be getting in the way of these social activities.

The easiest way to maximize income for minimal expenditure is to just steal. Why give the customer anything in exchange for his/her money? With a $500 handgun (always work with good tools) you can take potentially tens of thousands of dollars. Submitted as guidance to aspiring CEO’s.

As workers become unshackled from move-inhibiting changes to health care they can switch jobs, moving to where they will make more and maximize their returns. ACA will drive up wages by unleashing the free markets onto the labor market. Study STEM and you’ll do great.

Venn, STEM is a sham. The so-called shortage is a shortage of cheap H1-B labor. Companies don’t want to hire US citizens. There are hordes of graying engineers that lost their jobs in the dot-com crash that were never employed again. I know many of them. After two years of job searching, I, myself, finally took a blue collar job after a very successful thirty year career as a software engineer. I kept looking for professional jobs, but the agencies were only interested in my immigration status and “citizen” is not a category they are looking for. Young people don;t study engineering any more because their engineer parents have warned them that their are no jobs. The best advice is to study finance or law and become a bankster or ambulance chaser.

“The best advice is to study finance or law and become a bankster or ambulance chaser.”

Why not study accounting, especially auditing, the all-weather profession, with a freakishly imbalanced supply-demand profile?

Tend to agree that there are a lot of unemployed STEM types in the US. My son has a PhD in physics. He is working in Europe. He can’t find work in the US. He has experience in supposedly some of the hottest IT areas but no US job. Go figure.

Follow the money.

Looking at the prices paid for stock buybacks one would have to conclude that the average CEO belongs in an index fund. Boondoggle with a capital B.

Mr. Bartlett underestimates the history and importance of limited liability; after all, the ability to raise capital through stock offerings would be very much diminished if investors were being asked to take on unlimited liability exposure for activities they do not manage or control. [Compare to the way modern charity depends on donations being tax-deductable.] Guilds had limited liability, as did joint-stock companies, and New York passed the first modern limited liability law in 1811. Our Founders felt a certain distaste for corporations precisely because of the way the corporate structure shields people from responsibility for their actions. Our modern conservatives, who love to harp on ‘morality’ and constantly insist that ordinary individuals take more “personal responsibility” and stop depending on the state, are bizarrely committed to giving corporations ever more power and while still further freeing them from responsibility — which, as the Founders knew, is a recipe for immorality.

Jack Ma, the guy who was rejected to work the fryer at the first KFC in China, the guy who rode a bicycle 10 miles each way to learn English by giving Americans walking tours, a guy who was too afraid to touch the first desktop PC he was ever in front of fearing it was too expensive to potentially damage, but now a 22 times over billionaire heading Alibaba and Alipay said it best:

#1. customer.

#2. employee

#3. shareholder

One of the most instructive reads in a while. I sure hope the cadre of presidential candidates, all elected officials and overpaid ‘C’ suite executives, read it. Facts galore, discredits many ideologically based misinformation beliefs.

Is there a reason … a good reason – why, when this line of thought is articulated/pursued by people on the political left, as it has for years and years now by various individuals, it gets dismissed and derided?

It’s good to see Berle & Means in your bibliography. That was indeed the classic work. It was also released as the Pecora Commission report, the report that led to the legal structures behind the economic growth from the 1930s into the 1970s. They argued that the modern corporation is an example of collectivism on steroids, though not in those terms. That is an excellent analysis. The modern corporation was then a new form of private property, one which did not confer the usual perquisites of ownership like control, use or benefit. They consoled themselves that high corporate taxes meant that the nation’s fate was bound up with the fate of its corporations, but that is no longer the case. Corporations, by virtue of their government charters, receive a bounty of government subsidies. They should pay for them.

Maximizing “shareholder value” is a liquidator’s goal, not the goal of someone who wants an operating entity. I could maximize Apple’s shareholder value by turning over its cash horde to investors as dividends, then borrowing everything their cash flow could support and releasing that as an additional dividend. This would leave the company without reserves and a big pile of debt that could clobber it in even a minor downturn or rise in interest rates. I could also further increase the shareholder value by freezing the development of future products and even the maintenance of existing products. (Why are they wasting money releasing security updates?) Apple does have a number of defensive measures in place. For example, their cash horde is outside the US and there would be a hefty tax bill if it were imported for distribution to shareholders. Whenever I hear them complain about this, I think “briar patch”. They also officially have only a minimal research budget, which eliminates an obvious efficiency target.

Yes, Hostess Foods is a prime example. The shareholder’s value was maximized, the long term employees were shafted and life long customers were deprived of their favorite snacks, but the shareholders made a bundle.

Thank you very much for this Bartlett post.

I would be happy if that were the true goal of corporations. From my perspective the goal of corporations to to transfer wealth from the worker, society and even shareholders to the management team!