Winners from globalisation

Speech by Ben Broadbent, Deputy Governor Monetary Policy

Bank of England

Scottish Council for Development and Industry, Aberdeen July 11, 2017

Two hundred and fifty years ago, a few miles south of here, Adam Smith began working on the Wealth of Nations. It was published a decade later, in 1776. So there were (at least) two revolutions that year, one marking the birth of a country, the other the birth of modern economics.

One of Smith’s main targets was the doctrine of mercantilism – the idea that international trade is a zero sum game, one you win by exporting more than your neighbour. He pointed out that, if it allows you to concentrate on things you do relatively well, and buy more cheaply the stuff that others do well, international trade can make both parties better off.

A precise definition of “relatively well”, in this context, had to wait until David Ricardo’s Principles of Political Economy, published in 1817. What matters for trading patterns, he explained, was not just absolute advantage – whether a domestic sector was more productive than its peers in other countries – but also its productivity relative to other sectors at home (“comparative advantage”). This was important, because it meant that, in principle, a country could have lower productivity across the board, in the production of every good, and still end up as a net exporter of some of them. But the basic points survive: there’s no reason to suppose that commerce across an international border is any less mutually beneficial than that within a single country; nor is there any reason to view imports as intrinsically bad.

Of course, you might feel differently if you happen to be in one of the sectors at a comparative disadvantage. In the mid-1970s, just as the post-war boom in global trade was getting started, the UK’s clothing and textile industry employed over 800,000 people. That’s one in every 30 jobs. As markets opened up international prices fell steeply and, over the following thirty years or so, the domestic industry all but collapsed. Output fell 65%, employment by 90%. It now accounts for one in every 370 jobs.

Not all of this reflects the effects of greater trade. Part of the post-war decline in textile employment – employment in manufacturing in general, in fact – reflected relatively rapid productivity growth, not cheaper imports. If it takes progressively fewer people to make the same amount of stuff you might expect employment to fall. Over time the share of jobs in manufacturing has fallen in every developed country, including in those regarded as industrial powerhouses, such as Germany and Japan.

But there’s little doubt that, for the UK’s clothing and textile businesses, globalisation mattered a great deal. And if you’re inclined to view de-industrialisation as a sorry tale, it can only be the sorrier for a sector that played such a prominent part in our history and in the industrial revolution in particular. During the ten years Adam Smith spent writing the Wealth of Nations, and a few miles further south of here, the inventor and entrepreneur Richard Arkwright was awarded patents for his new spinning and carding machines. He opened his famous mill at Cromford in 1776, the same year as the book was published. By 1790 mills using his new machines employed 30,000 people. By the 1820s, Britain was producing half of the global cotton textiles1. Famously, in his two-sector example of the principle of comparative advantage, Ricardo chose Portuguese wine and “English cloth”.

And yet it is still worth bearing in mind Smith and Ricardo’s basic insights. If people can move relatively easily from one job to another, employment needn’t fall in aggregate even if it’s doing so in one particular sector. (Nationally, the rate of employment is significantly higher and the rate of unemployment far lower than in the mid-1970s.) And in the meantime, we have all had the benefit of cheaper clothes. Those as long in the tooth as me will know that, even in nominal terms, it costs less to buy a pair of jeans and a t-shirt today than it did thirty or forty years ago. The result is a significant contribution to real income growth over that period.

In what follows I’ll flesh out these numbers a little further and say something too about their distributional effects. (One particular point in this respect is that the real income benefit of lower import prices is probably most marked for those at the lower end of the distribution.) I’ll mention the parallels, long recognised by economists, between the effects of growing trade and those of technical progress, and the role of the latter in rising inequality in the US. I’ll conclude with some remarks about the sort of things economists might have to think about as the UK leaves the EU.

Globalisation and its effects on UK clothing

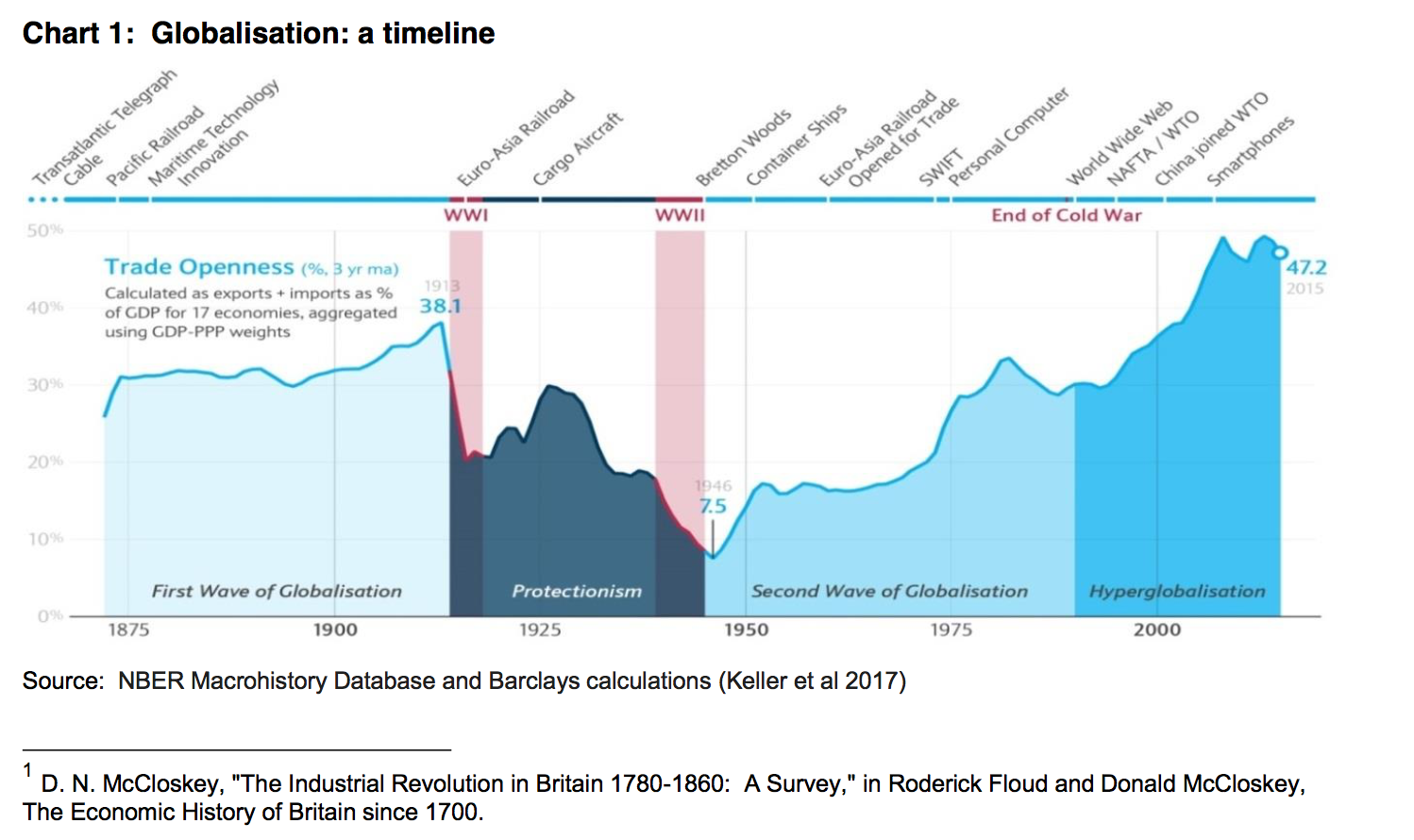

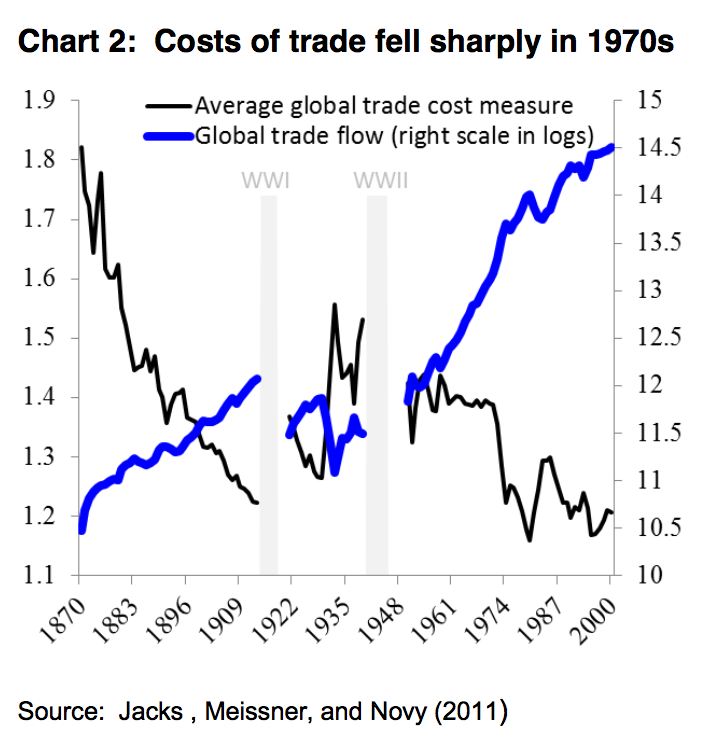

Globalisation hasn’t occurred smoothly nor is there a single, discrete date at which it began. Its broad features are reasonably clear in Charts 1 and 2.

One is that the current extent of world trade isn’t entirely novel and should in some ways be seen as a recovery. World trade had grown very strongly under the classical gold standard, during the second half of the 19th century. The same goes for the capital flows that financed these exchanges. The catastrophes of the world wars, and the intervening Great Depression, put all that into reverse. Partly as a natural consequence of economic contraction, partly thanks to outright protectionism, trade volumes fell sharply between 1914 and 1950, even relative to world GDP.

Speech by Ben Broadbent of the Bank of England