Source: Both Sides

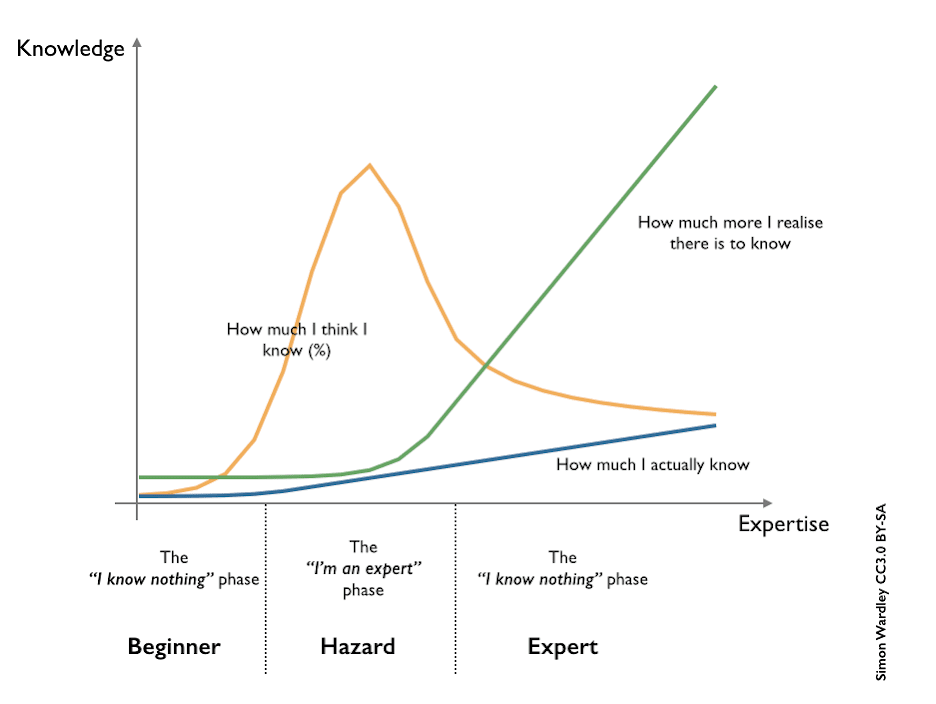

I love this Simon Wardley chart above, found via Mark Suster.

It is richly filled with insights from psychology, with Dunning Kruger’s concept of meta-cognition as a skill, and just for fun, the Socratic paradox of “The only thing I know is that I know nothing.”

This is worthy of a longer exposition, which I will attempt once I recover from the minutia of USPS health care legislation; for now, a quick few thoughts.

I pay lots of attention to meta-cognition, and how when we develop skills we also learn the separate skill of self-evaluation. This is of enormous importance to traders and investors; I find it fun to bring in parallel experiences from other realms. Recently, it has been radio and tennis. Both are interests I have come to late in life, starting each in my early 50s, with no background in either.

Tennis is hard, as anyone who watches the U.S. Opens can see. I was surprised to learn Radio was even harder.

To succeed at tennis, you need to master a series of technical mechanics, along with timing, footwork, proper distance, eye-hand coordination, mobility and an intriguing mental game. As someone who has always had issues with proprioception (I am a klutz), these physical mechanics are challenging.

When a project is progressing too slowly, seeking out expert help is advised. So I did.

Going slow to go fast applies to driving fast on a race track as well as playing tennis well. I learned that it is not merely about hitting the hardest or being the fastest to the ball. I was terrible two years ago, but via a helpful former pro player, a few modest technical changes made me significantly better. The mechanical body positionings made my forehand better, I developed a backhand (where previously I had none) a drop shot and slice shot came along, and the beginnings of an actual serve appeared. I was much, much better than before.

But this is not to say I was any good. What was most shocking to me was as I improved, I came to realize how truly terrible I was. Where previously I imagined myself to be a 4 or 5 on a scale of 10, my improvements came with lowered self-rating. Am I a 4? No wait a 3, no, worse, barely a 2.

Understanding meta-cognition abstractly was one thing, but living it was an entirely different thing.

Radio was much worse.

The idea behind Masters in Business was always pretty simple: find intelligent, successful people, and rather than ask them ephemeral nonsense – “What’s your favorite stock, when will the Fed raise, where will the Dow be in a year? – have instead an adult conversation about who they are and how they got that way.

My assumption was the content alone would be sufficient. Hey, how hard is it to talk? We do it every day. It took about 30 shows to disabuse me of that notion.

Al Mayers was Bloomberg’s head of radio. Each week, he would patiently pull me aside and deconstruct the last show – explain interviewing tactics, listening skills, how to pick up subtle things the guest said and then follow up. It was a crash course at not sucking at radio.

Almost 4 years later, and nearly 200 shows, and I can honestly say I have improved from thinking I was a 5 when I was really not quite a 2, to becoming a 6 with occasional glimpses of 7 or 8. This is not artificial humility – if you ever get a chance to watch Tom Keene in the radio studio do a dozen things at once, live on the air, without making an error, you will be in awe. I now know exactly what achieving that level 10 looks like and how much more there is to go to get there.

As always, there are life lessons and investing skills to be pulled from these experiences.

What do you erroneously believe you are great at?