The First Rule of Dunning Kruger…

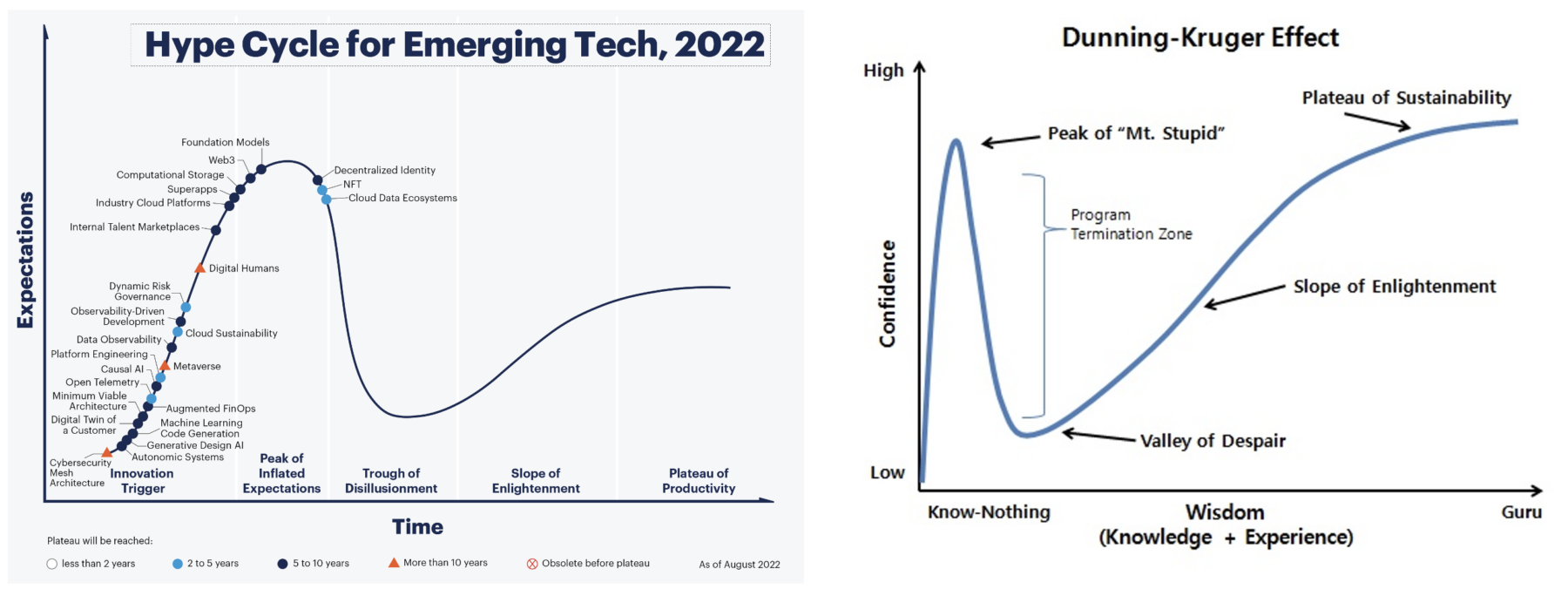

Of all the cognitive errors in behavioral finance and human psychology, the one that creates the most confusion is the Dunning-Kruger effect. (Perhaps its rise in pop culture is to blame). Regardless, I find DKE to be an incredibly useful tool that helps explain many of the individual errors we see in investing.

It’s useful to think of Dunning Kruger in terms of metacognition: One’s ability to self-evaluate a particular skill set. Metacognition appears to be a discrete skill unto itself, one that unsurprisingly increases along with the underlying skill. As you improve at a “thing,” your ability to evaluate your skills at that “thing” also increases.

Note that “Unskilled and unaware of it” is more than mere overconfidence, hubris or incompetence; it’s a very specific way to describe not just an overestimation of skills, but a way to framing that helps us understand why that error occurs, and how it manifests in human decision-making.

Yes, the least competent suffer from the Dunning-Kruger effect, but so too do those of average competency, albeit by a lesser degree. Even experts can show the effects of DKE, as their deep knowledge and awareness of difficulty may lead them to underestimate their own abilities.

Metacognition is a tricky thing.

There have been repeated attempts at debunking Dunning Kruger over the years, typically by mathematicians arguing a lack of statistical significance versus mere random noise. I remain unconvinced by those arguments, especially given that larger studies have confirmed the original underlying research.

About those experts: It is a feature of the genre that some very smart people can suffer from “deformation professionnelle” – a DKE-related tendency to view the world through the lens of one’s own profession. Hence, we should not be surprised that a mathematician looks at a psychological phenomenon and sees only the statistics.

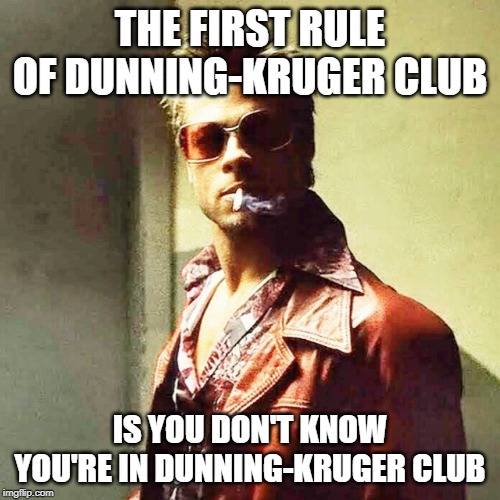

“Does anyone know what Dunning Kruger actually is?” has a delightful recursive character – the first rule of DKE is you don’t know you are in DKE – and has a fractal-like character that mathematicians should appreciate.

The all too obvious irony of a mathematician performing statistical analysis on psychology research unaware of the potential error in the psychological half of his analysis is from whence we get our title: The first rule of Dunning Kruger club is that you do not know you are in Dunning Kruger club…

UPDATE: May 25th, Noon

I reached out to Professor David Dunning, who adds:

“One universal problem is we don’t know how shallow our understanding is. DKE critics construe the research as being one or two studies from 1999, hard stop. Either they do not realize the complex story that has emerged after 20+ years of research, and data contrary to their conclusions, or haven’t taken the pains to survey the current literature, whether about the specific DKE they critique or the trouble with knowing your ignorance in general.

Consider in psychology the related phenomenon of the illusion of explanatory depth. Ask people if they can describe how a helicopter (or a bike, or zipper) works and they answer “Of course!” Then ask them to do so and they quickly realize the large gaps in their knowledge…”

That really helps fill out the academic debate…

Previously:

What if Dunning Kruger Explains Everything? (February 27, 2023)

MiB: David Dunning on Metacognition (March 21, 2020)

Sources:

Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments

Kruger, J., & Dunning, D.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 1999

Yes, The Dunning-Kruger Effect Really Is Real

Stuart Vyse

Rational Skeptic, April 7, 2022

The Dunning-Kruger effect revisited

Matan Mazor & Stephen M. Fleming

Research Department of Experimental Psychology, April 8, 2021

A rational model of the Dunning–Kruger effect supports insensitivity to evidence in low performers

Rachel A. Jansen, Anna N. Rafferty & Thomas L. Griffiths

Nature Human Behaviour, February 25 2021

See also:

Debunking the Dunning-Kruger effect – the least skilled people know how much they don’t know, but everyone thinks they are better than average

By Eric C. Gaze,

The Conversation, May 23, 2023

Math Professor Debunks the Dunning-Kruger Effect

By Eric C. Gaze

SciTechDaily, MAY 9, 2023