Macro Factors and their impact on Monetary Policy

the Economy, and Financial Markets

MacroTides@macrotides1@gmail.com

Investment letter September 20, 2011

;

How Much Longer?

One of the standard family car trip experiences was children asking “How much longer?” Sometimes even before the car had left the driveway! If they waited for more than 30 minutes, it was a real sign they were growing up. Invariably, even a saint’s patience wears thin, and long before the destination was in sight, the question would be asked repeatedly, How much longer? A good parent would answer “Not much longer, sweetie”, no matter how many hours remained on the drive. It’s been three years since Lehman Brothers failed, and to say the recovery has been a disappointment would be generous. The rebound since the recession that was officially proclaimed over in June 2009 has been weak, with a number of statistics suggesting the recession never truly ended. It’s been a difficult three years for the majority of Americans and most want one question answered, “How much longer?”

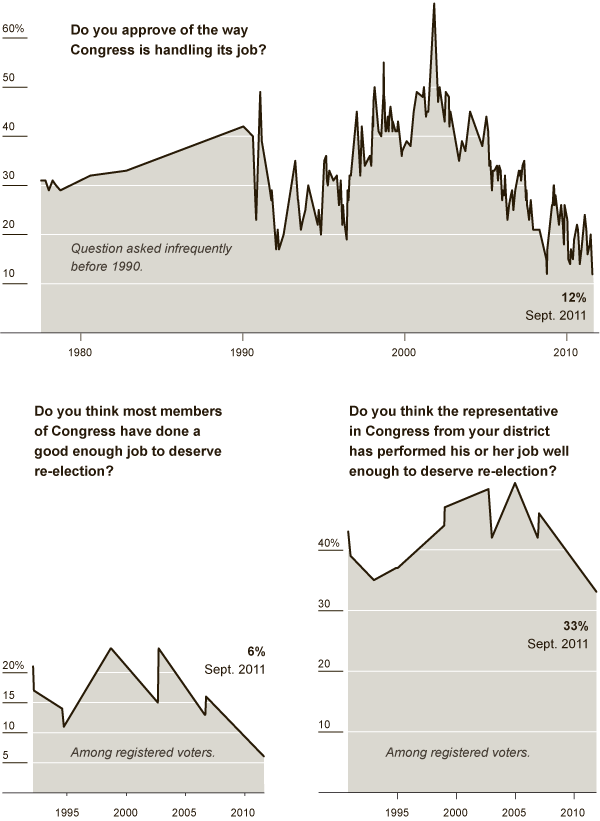

Most politicians (especially if they fear their own job is at risk) would look into the camera and say “Not much longer.” Those politicians seeking office, would boldly proclaim, “Not much longer, if I am elected!” Unfortunately for the current crop of politicians, their message is not being delivered to kids in the car’s backseat, but into family rooms throughout our country to millions of adults, who are simply disgusted with the leadership vacuum that promises more tough times. In the latest New York Times/CBS News Poll only 12% of respondents approved the way Congress is handling its job. The remarkable point is not that 88% of registered voters were unhappy with Congress, but that there were still 12% who approved! Only 33% felt their Congressperson deserved to be reelected.

We have stressed since mid 2009 that the myriad of structural imbalances we are facing took decades to build up, and, therefore, would not be unwound quickly. The interconnectedness between all the headwinds holding growth down suggests this trip is going to last years. (weak job and income growth, lower home values, soft consumer spending, inadequate tax revenues at all levels of government, underfunded private and public pensions, historically low interest rates which punishes savers and pension actuaries, an aging population bulge, trillions in unfunded liabilities in the Medicare and Social Security programs, unsustainable safety net expenditures that prevented a deeper contraction, and the need to cut government spending in the not too distant future) We probably missed something, but this list is long enough to discourage even the most stalwart optimist.

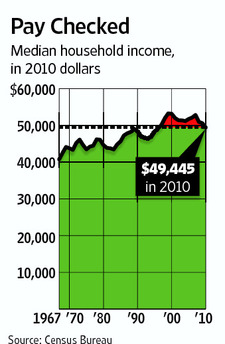

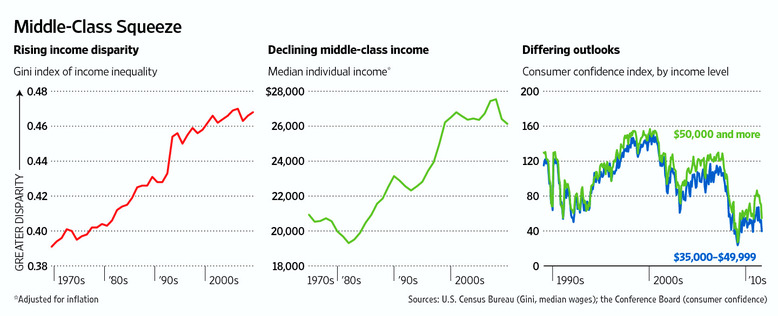

Job and income growth are the two most important drivers of the economy, since they fund consumer spending and government spending through personal income taxes and sales taxes. More than 84% of those wanting a full time job have one, but their incomes are not growing. According to the Census Bureau, median household income is 7.1% below its peak in 1999. After falling for three consecutive years, it was $49,445 in 2010, and roughly equal to its 1996 level when adjusted for inflation. Even as middle class Americans have been squeezed for more than a decade by a lack of income growth, they have also been hurt by an imbalance of income disparity that has been gradually worsening since the late 1960’s.

The Gini index measures the extent to which the distribution of income among individuals or a household within an economy deviates from a perfectly equal distribution. A Gini index of zero represents perfect equality and 1.00 equals perfect inequality. According to the Census Bureau, the Gini coefficient totaled .468 in 2009, the most recent calculation available. This suggests income disparity has risen by 20% over the last 40 years.

The Gini index measures the fairness of income distribution, and not the absolute income of a country. Despite all our troubles, the average American worker still earns more each year than other workers throughout the world. However, in terms of income distribution, the United States sports a Gini index that is comparable to Mexico and the Philippines.

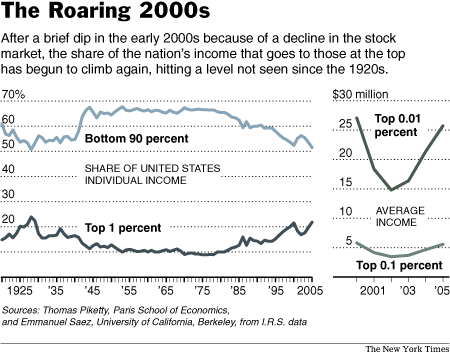

As we wrote in our July letter, “In the 1960’s, the average CEO was paid 35 times the average workers’ income. Last year, the CEO of a public company was paid 350 times the average worker’s pay. We don’t believe anyone is worth that much money to run a company. But, if the Board of Directors of a public company believes they must pay that much in compensation to attract ‘talent’, and shareholders don’t object, we see nothing wrong with it. At the same time, the gap in wages between the average working stiff and a CEO is just too large to ignore. The income for the top 1% reached 23.5% of total income in 2007, which is just a hair below the level reached in 1928. These income figures include capital gains and income from stock options. Although raising taxes on this elite group won’t raise that much in taxes, it will serve as an appropriate symbol.

As we wrote in our July letter, “In the 1960’s, the average CEO was paid 35 times the average workers’ income. Last year, the CEO of a public company was paid 350 times the average worker’s pay. We don’t believe anyone is worth that much money to run a company. But, if the Board of Directors of a public company believes they must pay that much in compensation to attract ‘talent’, and shareholders don’t object, we see nothing wrong with it. At the same time, the gap in wages between the average working stiff and a CEO is just too large to ignore. The income for the top 1% reached 23.5% of total income in 2007, which is just a hair below the level reached in 1928. These income figures include capital gains and income from stock options. Although raising taxes on this elite group won’t raise that much in taxes, it will serve as an appropriate symbol.  The austerity that must be imposed on government spending will prove a hardship on almost half of the 300 million citizens in this country. For most of those in the top 1% of income, higher taxes will be more of an inconvenience than an actual hardship.” Sooner or later, the income distribution gap will have to be narrowed.

The austerity that must be imposed on government spending will prove a hardship on almost half of the 300 million citizens in this country. For most of those in the top 1% of income, higher taxes will be more of an inconvenience than an actual hardship.” Sooner or later, the income distribution gap will have to be narrowed.

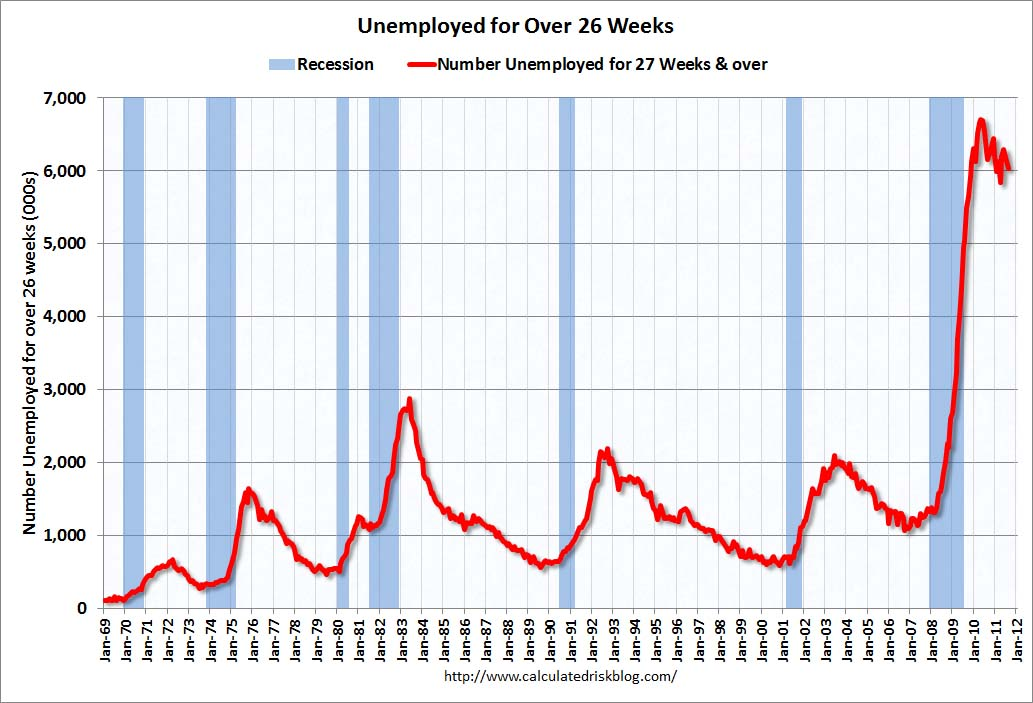

In August, no jobs were created, and the unemployment rate remained unchanged at 9.1%. Another 8.8 million workers, or 6.7% of the labor force, are working part time, but would prefer a full time job. The number of hours worked fell as did hourly pay. Over the last year, the average worker’s pay increased 1.9%, well below the increase in the cost of living. Six million workers have been unemployed for more than 27 weeks. The US has not experienced anything like this since the 1930”s. The longer someone is unemployed, the more their skills erode and they fall further behind the curve.

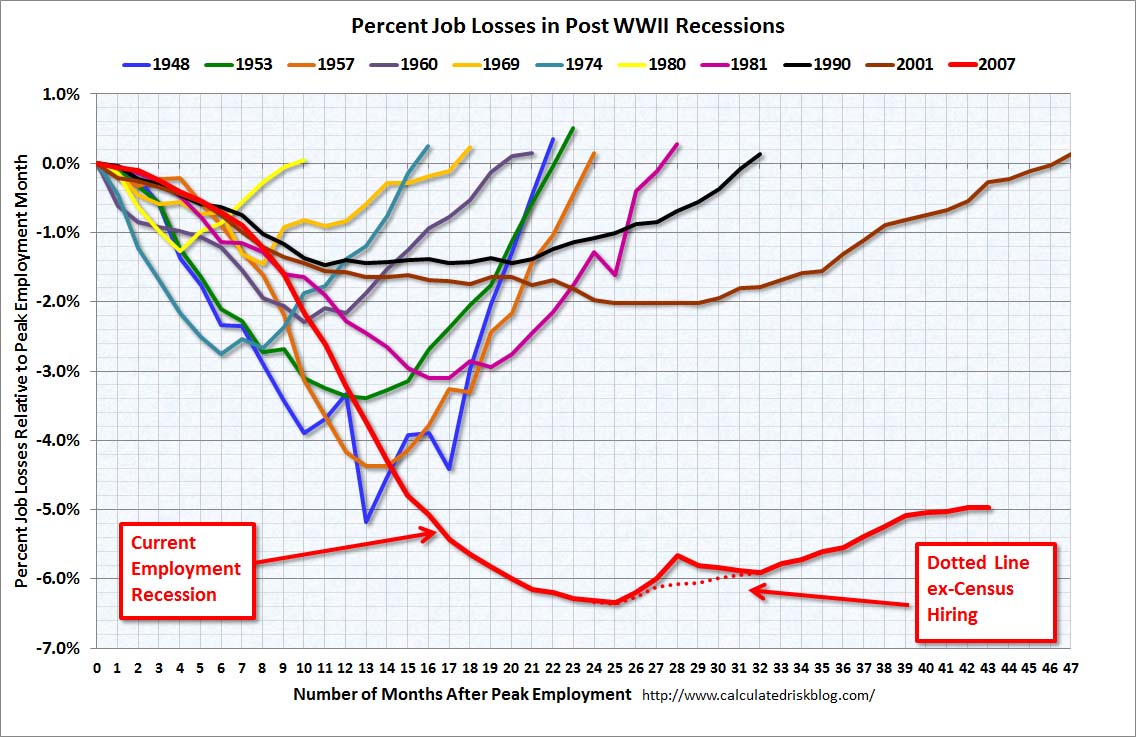

Forty three months after the recession began in January 2008, almost 5% of the labor force remains unemployed. In 7 of the eleven recessions since World War II, all the jobs lost during the recession were filled within 24 months. What’s happening in this ‘recovery’ is simply unprecedented.

Forty three months after the recession began in January 2008, almost 5% of the labor force remains unemployed. In 7 of the eleven recessions since World War II, all the jobs lost during the recession were filled within 24 months. What’s happening in this ‘recovery’ is simply unprecedented.

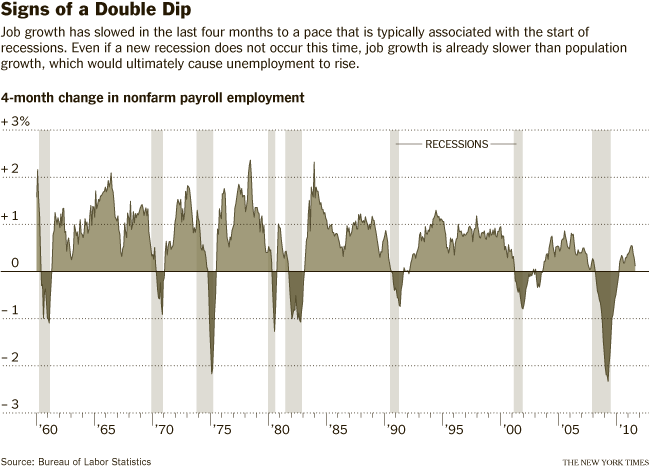

Another way of measuring the depth of job losses and the quality of the recovery is to look at a 4 month change in non-farm payroll employment. Since 1960, the only recession that equates to the magnitude of job losses experienced in 2008-2009 occurred in the 1973-74 recession. In the wake of that recession, employment growth virtually exploded with the 4 month change exceeding 2.2%. The deep recession in 1981-81 was also followed by a significant snap back in employment 2.2%. Based on this metric, the rebound in jobs to .5% is less than 25% as strong as the 1975 and 1983 recoveries.

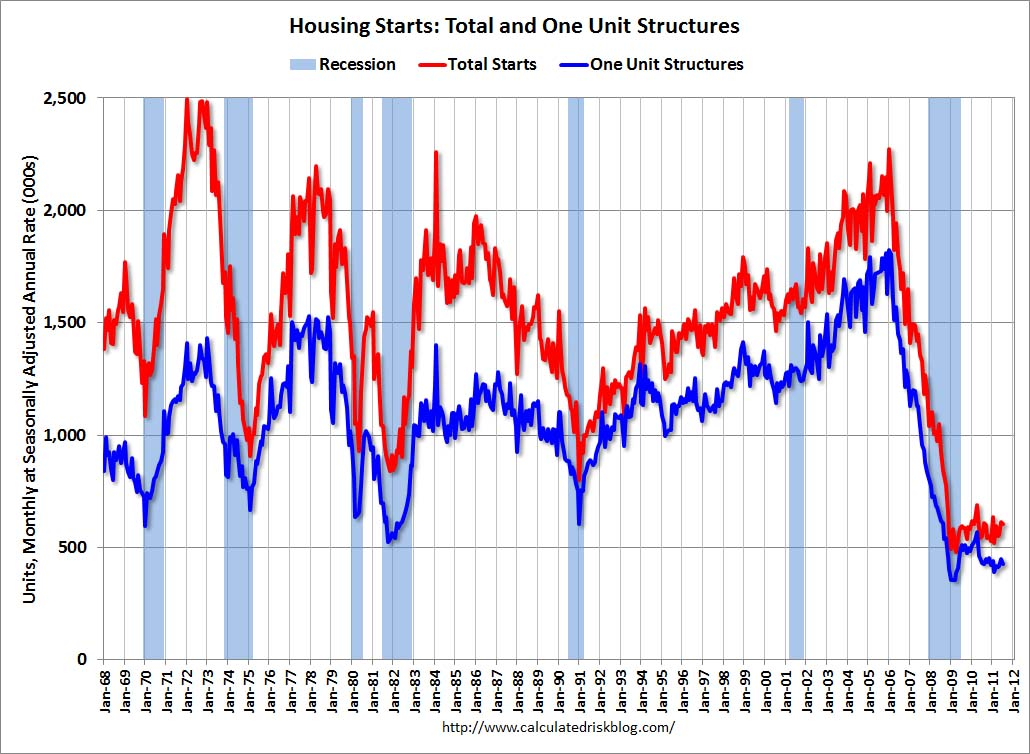

In the last 40 years, the growth in home construction contributed significantly to the economic rebound that followed each recession. Despite record low mortgage rates and record affordability, housing starts hover at the lowest levels since 1963. There are a number of reasons why there is no pent up demand as in prior cyclical recoveries. The lack of job growth has certainly played a role. However, the 30% decline in home prices may have improved affordability, but it has eroded current and future demand as never before. More than 25% of homeowners are underwater according to CoreLogic, which precludes them from refinancing and benefitting from the lowest mortgage rates in history. Even if they can afford their current mortgage, few can afford to sell since they would lose all their equity and most don’t have the savings for a new down payment. As long as home prices languish, more than 25% of future demand is gone. Higher lending standards have also shrunk the demand pool by another 5% to 10%, for at least another two years. This suggests that demand will be 35% lower or more for several years.

On the supply side, there is a substantial shadow inventory of foreclosed homes that will be disposed of over the next two years. This forced selling will weigh on prices, especially in the states it is concentrated, Florida, California, Arizona and Nevada. In addition, an increasing number of baby boomers will be downsizing, either voluntarily or because they need their home equity to fund a portion of their retirement. With demand and supply so imbalanced, it is difficult to see home values rising before 2014, with a greater probability that prices will fall further.

On the supply side, there is a substantial shadow inventory of foreclosed homes that will be disposed of over the next two years. This forced selling will weigh on prices, especially in the states it is concentrated, Florida, California, Arizona and Nevada. In addition, an increasing number of baby boomers will be downsizing, either voluntarily or because they need their home equity to fund a portion of their retirement. With demand and supply so imbalanced, it is difficult to see home values rising before 2014, with a greater probability that prices will fall further.

The impact of weak income and job growth, along with no rebound in housing can be seen in how the overall economy has performed. In every recovery since 1948, as measured by Gross Domestic Product, it has never taken more than 3 quarters to recoup all the lost ground during the prior recession, until now. It has been 8 quarters since the recession ended in June 2009, and GDP is still below the level reached at the end of 2007.

The impact of weak income and job growth, along with no rebound in housing can be seen in how the overall economy has performed. In every recovery since 1948, as measured by Gross Domestic Product, it has never taken more than 3 quarters to recoup all the lost ground during the prior recession, until now. It has been 8 quarters since the recession ended in June 2009, and GDP is still below the level reached at the end of 2007.

This weak recovery is happening despite a record level of fiscal stimulus. According to the Congressional Budget Office, the federal government will spend $2.0 trillion in government social benefits in the fiscal year that ends on September 30. Income transfers will total 17% of total income, a record. Somewhat alarming, total personal income and social insurance taxes will total $1.9 trillion. This deficit of $100 billion contrasts with the $500 billion surplus in 2007 between social benefits and taxes. As we have noted previously, disposable income would be down 4% from 2007, rather than up 4% as a result of government safety programs, i.e. unemployment benefits, food stamps for 46 million Americans, and the unearned income and child tax credits. Clearly, the recession would have been deeper and the recovery even more feeble had these programs not been in place to support aggregate demand. However, this level of spending is unsustainable, and no replacement for healthy income and job growth.

The focus of any job creation program must be on private sector jobs. We don’t think the President’s proposal goes far enough. And, to be meaningful, any viable program must offer incentives that last for more than one year. The fact that the President’s plan expires two months beyond the next election is a simple coincidence. Of that, we’re sure.

The focus of any job creation program must be on private sector jobs. We don’t think the President’s proposal goes far enough. And, to be meaningful, any viable program must offer incentives that last for more than one year. The fact that the President’s plan expires two months beyond the next election is a simple coincidence. Of that, we’re sure.

Over the last year, consumer inflation has climbed to 3.8%, while producer prices are up more than 6%, according to the Labor Department. Even core inflation has pushed up to 2% from 1%. The uptick in inflation complicates the Federal Reserve’s flexibility to provide more monetary accommodation, should the recent slowing in the economy persist or accelerate. When the Fed announced it was defining ‘extended period’ to mean it would keep rates low for two years, three members of the FOMC voted against the change. Their primary concern was that inflation might intensify in coming months, and risk the Fed’s inflation credibility. Most FOMC votes are unanimous. Occasionally, one member might dissent. For three to dissent is truly rare. Given the recent inflation news, the doves on the FOMC will announce more accommodation at the September 20-21 meeting. The Fed’s statement will likely emphasize that the Fed has many tools it can use, if and when they are needed. That will spark speculation that the Fed will move at the November meeting.

Europe

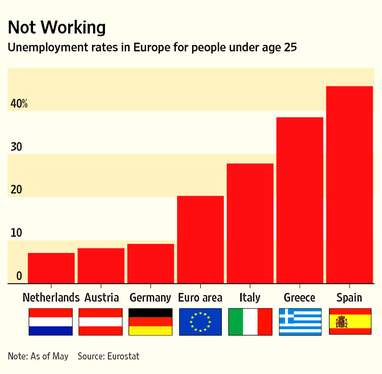

Last month we asked a simple question, “What happens when monetary and fiscal policy hit the wall?” This question is not only pertinent for the United States, but also for almost every developed country, since most of the G7 nations are confronting many of the same problems and the same monetary and fiscal limitations. Monetary policy in the US and other G7 countries is basically running on empty. Fiscally, debt levels are high and growing, while economic growth is weak and slowing. The net result is debt to GDP ratios continue to rise. The reductions in government spending to rein in excessive budget deficits will only dampen growth further, or cause a further contraction in GDP as illustrated by Greece. The unemployment rate for people under 25 years old is 20% throughout the EU, and far higher in Italy, Greece and Spain. In the US, the unemployment rate for those under 19 is 25.4%. As these high unemployment rates become chronic, social unrest and violence will become common place. Labor strikes will disrupt everyday life, as the economic stress intensifies all over the world.

Monetary policy in the US and other G7 countries is basically running on empty. Fiscally, debt levels are high and growing, while economic growth is weak and slowing. The net result is debt to GDP ratios continue to rise. The reductions in government spending to rein in excessive budget deficits will only dampen growth further, or cause a further contraction in GDP as illustrated by Greece. The unemployment rate for people under 25 years old is 20% throughout the EU, and far higher in Italy, Greece and Spain. In the US, the unemployment rate for those under 19 is 25.4%. As these high unemployment rates become chronic, social unrest and violence will become common place. Labor strikes will disrupt everyday life, as the economic stress intensifies all over the world.

Last week, the Federal Reserve, Bank of Japan, Bank of England and the Swiss National Bank, said they would provide the European Central Bank with unlimited dollar funding for the remainder of this year. After receiving dollar funding from the other central banks, the ECB will lend to banks throughout Europe who are having difficulty accessing short term funding.  This illiquidity squeeze has developed as US money market funds reduced lending to European banks by $700 billion in recent months, according to JP Morgan Chase. According to Credit-Sights, at the end of June, bank lending between Euro-zone banks fell by $600 billion from year ago levels. It has no doubt fallen further in recent weeks. European banks have become so fearful of lending to other European banks that deposits at the Federal Reserve have soared to $849 billion.

This illiquidity squeeze has developed as US money market funds reduced lending to European banks by $700 billion in recent months, according to JP Morgan Chase. According to Credit-Sights, at the end of June, bank lending between Euro-zone banks fell by $600 billion from year ago levels. It has no doubt fallen further in recent weeks. European banks have become so fearful of lending to other European banks that deposits at the Federal Reserve have soared to $849 billion.

The underlying problem is that European banks are loaded with holdings of sovereign debt from Greece, Portugal, Spain and Italy. Not long ago, the sovereign debt of these countries was rated AAA, and holding sovereign debt was considered a sign of balance sheet strength. Not anymore. The recent European bank stress test used a 21% discount for Greek sovereign bonds, which are now selling at a 60% discount to face value. Many large banks would be insolvent if they had to mark to market their holdings of Greek bonds. And, to a far lesser extent, their holdings of Spain and Italy, which have also lost value. The only viable solution is a large recapitalization of many European banks.

The central banks’ arrangement to provide dollar funding to alleviate a severe short term funding problem does not address the real elephant in the room. There is too much debt sitting on bank balance sheets, and too little economic growth in too many EU countries to support the mountain of debt they are carrying. At the end of June, annual GDP growth was up .8% in Italy, up .7% in Spain, and down by .9% in Portugal and 7.3% in Greece. According to ECB data, bank lending over the past year was down 9% in Ireland, 3% in Greece and Italy, and 1% in Portugal and Spain. Given the recent turmoil, it’s a safe bet lending has contracted further. This will lead to even slower growth in coming months in these countries, and in Germany too. The European debt crisis is going to get worse, and it will have a negative effect on global growth.

China, India, and Brazil

The Peoples Bank of China has been tightening monetary policy since last October, through a series of interest rate increases totaling .75% in 2011, and nine increases in the bank reserves ratio from 15% to 21.5%. For every $1 of lending, Chinese banks must hold $.215 in reserve, which has resulted in higher borrowing costs. The average yield on top-rated, one-year corporate notes have risen 101 basis points since June 30 to 5.9 percent, and is poised for the biggest quarterly increase going back to 2007. Chinese inflation slowed to 6.2 percent in August, from a three-year high of 6.5 percent in July, but is still far above the official target. Monetary tightening has slowed growth, with the economy expanding 9.5 percent last quarter, the slowest since 2009.

The Reserve Bank of India raised interest rates for the 12th time in 18 months on September 15 to 8.25%. India’s benchmark wholesale price index hit a 13-month-peak of 9.78% in August, well above the bank’s comfort zone of 5.0%. India’s inflation is the highest of any large global economy.

After raising interest five times this year to combat inflation, Brazil’s central bank cut rates on September 1 from 12.5% to 12%. The central bank said high debt and weaker growth in developed economies could slow Brazil’s economy, which is still expected to grow by 5% over the next year. Inflation is 6.9%, which made the cut a bit of a surprise. However, the Brazilian Real has appreciated 50% since early 2009, which has made Brazilian exports expensive. Lower rates may bring the Real down, and help export growth offset some of the global slowing.

The tightening of monetary policy over the last year by China, India, and Brazil will cause their domestic economies to slow. Coupled with the slowdown in developed countries, global growth is set to slow for the rest of 2011 and early 2012.

Stocks

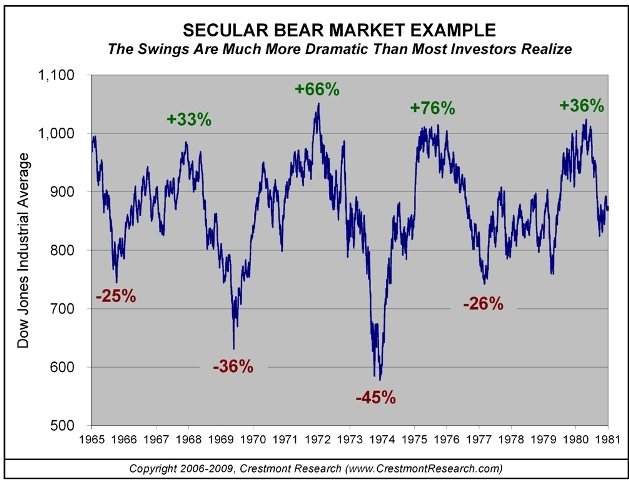

We believe the U.S. stock market is in a secular bear market that could last until 2014-2016, and could prove similar to the secular bear market that held the DJIA in a broad trading range during 1966-1982. This secular bear market could extend until 2020 or longer, since it is associated with the largest financial crisis in history. As discussed last month, the structural imbalances that need to be corrected are unprecedented, and may require more time to work through than the 16 years of the 1966-1982 experience. Monetary policy was effective during the 1966-1982 bear market, since it was focused on curbing inflation. The Federal Reserve raised rates to lower inflation in 1969-1970, 1973-1974, and 1981-1982, which caused the stock market to fall and the economy to eventually slip into recession. A pool of pent up demand for housing and autos was created every time the Fed raised rates, since they are interest rate sensitive. Once the Fed cut rates, it unleashed the pent up demand, and the recovery was off to the races. In the current environment, the Federal Reserve is battling deflation, and has lowered rates to near zero with minimal impact on the demand for housing and autos. This means the Federal Reserve’s most powerful tool in managing the economy has been neutered.

Once the Fed cut rates, it unleashed the pent up demand, and the recovery was off to the races. In the current environment, the Federal Reserve is battling deflation, and has lowered rates to near zero with minimal impact on the demand for housing and autos. This means the Federal Reserve’s most powerful tool in managing the economy has been neutered.

It is our hope that the low in March 2009 will mark the nadir of this secular bear market, just as the December 1974 low marked the low point of the 1966-1982 trading range. After the DJIA bottomed in 1974, it spent more than 7 years trading between 1,000 and 700, even though in terms of the stock market, the worst was over. A similar window of time would target late 2015 or early 2016 for the next secular market bottom.

The rally from March 2009 was a cyclical bull market within the context of the longer term bear market. We believe the cyclical bull market rally ended in early July, and a new bear market has begun. If this macro analysis is correct, at least one more decline of 25% to 35% will occur during the next five years, before the current secular bear market ends. Given the European banking crisis and the fragility of the recovery in the U.S., it is not hard to see the S&P 500 falling to 1040 or 950 in coming months.

In the Special Update on September 7, we noted that the Major Trend Indicator had provided a bear market rally buy signal, with the S&P at 1198.62. Based on a number of measurements we thought the S&P could reach 1259 to 1265. We also noted that the rally might even be over. “After dropping from 1230 to 1140, the S&P recovered .618% of the 90 point decline it suffered between Thursday and yesterday morning, near today’s high. (1230-1140 = 90 *.618 = 56 + 1140 = 1196.) Although not likely, it’s possible the rally is over! Yikes!” After pushing up to 1204 on September 8, the S&P quickly reversed, and by September 9 the buy signal was reversed. Whip saws are never fun, but they do happen, no matter how good a momentum indicator may be, and the Major Trend Indicator is pretty good. We ended the Special Update with the following comment. “The most important point we can make is that the odds favor the S&P falling below 1101 sooner or later, since a new bear market likely began in early August.”

Although a rally up to 1250 is still possible, we’re not going to play, given the potential of a quick decline that could erupt almost any day if Europe deteriorates further. If the S&P does fall below 1101, we will send out a Special Update.

Dollar

In our May letter we recommended going long the Dollar via its ETF (UUP) at $21.56, and in our July 31 Special Update, we suggested adding to the UUP position below $20.91. The troubles in Europe have hurt the Euro, boosting the Dollar as we expected. We think UUP will trade above $23.00 in coming months.

Bonds

As long as the 10-year Treasury yield is below 2.45%, we view it as a warning sign of further banking problems in Europe, and economic weakness in the U.S.

Gold

As long as gold holds above $1700, the trend is still up. Paradoxically, gold stocks and gold could be vulnerable if the European banking crisis intensifies, and causes institutional investors to sell their winners to raise cash.

What's been said:

Discussions found on the web: