Factors and their impact on Monetary Policy

Factors and their impact on Monetary Policy

the Economy, and Financial Markets

MacroTides@macrotides1@gmail.com

Investment letter – January 13, 201

l

j

Is Decoupling Possible in a Global Economy?

An improvement in U.S. economic data in the fourth quarter has convinced many investment strategists that the U.S. will continue to grow 2% to 3% in 2012, absent a Lehman Brothers type of crisis in Europe. After all, U.S. GDP growth likely exceeded 3% in the fourth quarter, while Europe was slipping into recession, and China’s growth throttled down 8% to 9%. Further evidence can be found in how equity markets performed around the world in 2011. In the U.S., the DJIA was up 5.5%. In Europe: Germany -14.6%, France -16.9%, Italy -25.2%, Spain -13.1%, Portugal -27.6%, Greece -51.8%. In Asia: South Korea -10.9%, Australia -14.5%, Singapore -17.0%, Japan -17.3%, Hong Kong -19.9%, China -21.6%, India -24.6%. In South America: Brazil -18.1%.

Hardly a day passes that a strategist or expert on a financial news broadcast doesn’t remind viewers that the stock market is always looking out six to twelve months, which is why it is a discounting mechanism. We’re told the market anticipates events like recessions, recoveries, and decoupling far better than we mere mortals. If the market does indeed peer into the fog of the future, the U.S.’s outperformance in 2011 should provide investors comfort about the next six to twelve months, right? As we have discussed on a number of occasions, we do not believe the stock market is a discounting mechanism, which anticipates economic events, i.e. recessions and recoveries. For instance, in March 2000, was the Nasdaq Composite telling us that the New Paradigm in technology would continue, so there was no need to worry, just be happy? At the top in October 2007, were the market’s tea leaves suggesting that the credit crisis would be contained, so there would be no recession, as most strategists and advisors believed? And, in March 2009, when the market indicated that the sky was indeed falling, were most strategists and advisors justified in being negative, because the market was plumbing new lows?

Hardly a day passes that a strategist or expert on a financial news broadcast doesn’t remind viewers that the stock market is always looking out six to twelve months, which is why it is a discounting mechanism. We’re told the market anticipates events like recessions, recoveries, and decoupling far better than we mere mortals. If the market does indeed peer into the fog of the future, the U.S.’s outperformance in 2011 should provide investors comfort about the next six to twelve months, right? As we have discussed on a number of occasions, we do not believe the stock market is a discounting mechanism, which anticipates economic events, i.e. recessions and recoveries. For instance, in March 2000, was the Nasdaq Composite telling us that the New Paradigm in technology would continue, so there was no need to worry, just be happy? At the top in October 2007, were the market’s tea leaves suggesting that the credit crisis would be contained, so there would be no recession, as most strategists and advisors believed? And, in March 2009, when the market indicated that the sky was indeed falling, were most strategists and advisors justified in being negative, because the market was plumbing new lows?

The majority of strategists and advisors who believe the ‘market is a discounting mechanism’ axiom can be compared to car drivers who navigate their way by looking in the rear view mirror. If the markets are consistent in at least one facet, it is they always take the long and winding road. When a majority of drivers peer into their rearview mirror and reflect on how lovely the drive has been, they won’t notice their car has left the road until it is airborne and in free fall. Of course, the opposite occurs at market bottoms. Drivers only see potholes and ditches in the rearview mirror, and feel as if they’ve been driving in the Baja 500 without shock absorbers forever. At every market top and bottom, the market is wrong. Not convinced? Just ask all those folks who bought condos in Florida, Nevada, and Arizona in 2006! For all our intelligence, we humans are too often induced to become herded by the newest craze, or an investment that seems to offer a sure fire path to riches. Whenever a herd mentality takes over, i.e. technology stocks in 2000 or housing in 2006, separating from the crowd is really difficult. But that’s what makes contrary opinion, one of the more powerful investment tools, and far more valuable than believing the market is a discounting mechanism.

Europe

Germany is the largest economy in the European Union and derives more than 35% of its GDP from exports. In the last five years, more than half of its growth in GDP has come from a surge in exports. This growth was largely the result of productivity gains relative to other countries in the EU. In effect, as the low cost producer, Germany became the China of the European Union.

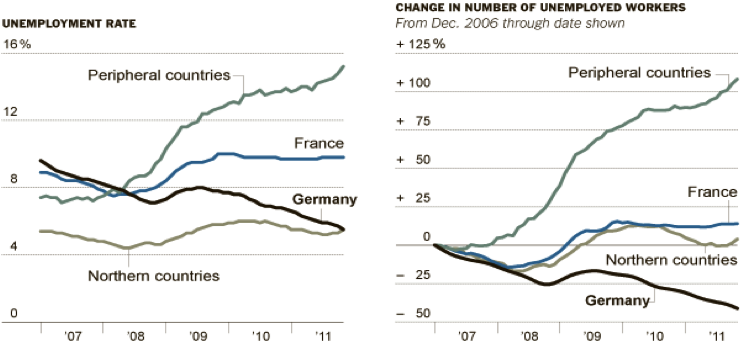

This productivity edge has lowered Germany’s unemployment rate from 9.6% at the end of 2006, to 6.8% in December, the lowest since 1991. In contrast, since the end of 2006, the rate of unemployment in France has risen to 9.8% from 8.9. The combined unemployment rate for the 10 periphery countries has soared from 7.4% at the end of 2006 to 15.2% in October. Italy’s unemployment rate reached 8.6% in November, but for those under age 24 it was over 30%. Greece’s overall unemployment rate is over 18%, and in Spain it is almost 23%.

This productivity edge has lowered Germany’s unemployment rate from 9.6% at the end of 2006, to 6.8% in December, the lowest since 1991. In contrast, since the end of 2006, the rate of unemployment in France has risen to 9.8% from 8.9. The combined unemployment rate for the 10 periphery countries has soared from 7.4% at the end of 2006 to 15.2% in October. Italy’s unemployment rate reached 8.6% in November, but for those under age 24 it was over 30%. Greece’s overall unemployment rate is over 18%, and in Spain it is almost 23%.

The differential in unemployment rates between members of the European Union underscores one of the major structural problems that will be painful to correct, and potentially socially unacceptable. Labor comprises 60% to 70% of the cost of goods. In order for the countries with high unemployment rates to be able to compete with Germany and globally, they must lower their production costs by 10%, 20% or even 30%. If the Italian Lira was still Italy’s currency, Italy could devalue the Lira by 20% and immediately lower its cost of production and increase its competitiveness within the E.U. and worldwide. This option is not available since Italy’s currency is the Euro. For Italy, and every other EU member country that has a cost of goods problem, the Euro is an albatross. In order to increase their competiveness, the workers in each country must accept a significant decline in wages in order to lower their country’s cost of production. This ‘internal devaluation solution’ not only creates a burden for the workers involved, but it also creates social and budgetary problems for Italy, Greece, and any other country in the E.U. that is uncompetitive. If a worker has less income, they have less income to spend and will pay less in taxes. In order for Greece and Italy to reduce their excessively high debt to GDP ratios, they need strong economic growth, and more workers paying taxes on rising wages. Obviously, this austerity ‘solution’ will not work, as workers unite, and launch labor strikes that will result in more social disorder in coming years.

The flags represent the US, Japan, Germany, France, Britain, Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece, and Spain.

The diminishing level of productivity in Greece and Italy over the last five years is a bit like rust. And, as we all know, rust never sleeps. Like many other developed nations, Italy was also affected by China’s emergence, and a lack of energy independence that became more costly as oil prices rose. Rather than adopting policies to address their weaknesses, both countries borrowed money on the back of low borrowing costs afforded members of the European Union, made even cheaper by a strengthening Euro. Greece is small enough to force private holders of its debt to accept a ‘voluntary’ haircut of 50% on their Greek bond holdings. This could lower Greece’s total indebtedness of $450 billion by about 30%. This will help. But, given Greece’s cost of borrowing and its shrinking economy, a default seems a foregone conclusion. There is also the possibility that some of the private holders of Greek bonds will not go along with the 50% haircut, since the ECB is scheduled to receive the full face value of their Greek bonds. Should private holders not go along with the current ‘voluntary’ haircut plan, a default by Greece could be triggered by March 20.

Italy has $2.7 trillion in debt, six times Greece’s total, so it is both too big to fall and too big to bail out. As we noted in the November letter, Italy’s average cost of funds in June 2011 was 4.2%. In 2012, Italy needs to roll $600 billion of its debt. Unless its cost of funds can be manipulated lower from current levels, Italy will find it more difficult to improve its fiscal condition. Real progress in lowering its debt to GDP ratio will only be made if Italy grows by more than 2%, which it has not accomplished in the last 10 years. Given its weak competitive position, and the austerity measures it is being forced to adopt by the E.U., we are skeptical.

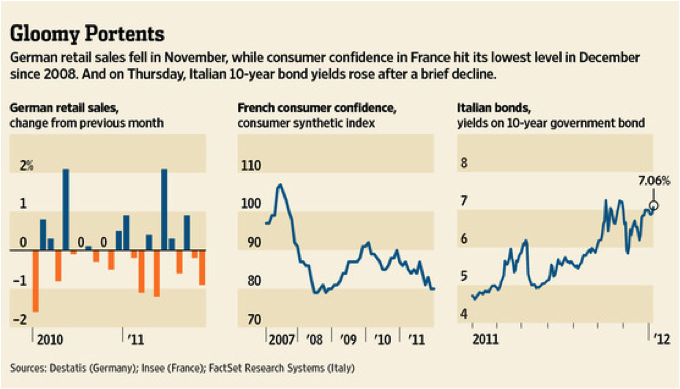

In the third quarter, the European Union grew .1%, which may have been the result of a rounding error. The European economy weakened in the fourth quarter. Eurozone retail sales fell .8% in November from October. According to Eurostat, more than 16 million people were unemployed in November, the highest since records were first compiled in 1995. In its first estimate of fourth quarter GDP, Germany reported a decline of .25% from the third quarter, or an annualized drop of 1%. Most of the other countries in the E.U. are weaker than Germany, so it is likely the E.U. as a whole contracted in the fourth quarter. The official definition of a recession is two consecutive quarters of negative GDP, so the E. U. is already halfway there. Most of the surprises in coming months will be negative, so the only question is how long and deep will Europe’s recession be.

In the third quarter, the European Union grew .1%, which may have been the result of a rounding error. The European economy weakened in the fourth quarter. Eurozone retail sales fell .8% in November from October. According to Eurostat, more than 16 million people were unemployed in November, the highest since records were first compiled in 1995. In its first estimate of fourth quarter GDP, Germany reported a decline of .25% from the third quarter, or an annualized drop of 1%. Most of the other countries in the E.U. are weaker than Germany, so it is likely the E.U. as a whole contracted in the fourth quarter. The official definition of a recession is two consecutive quarters of negative GDP, so the E. U. is already halfway there. Most of the surprises in coming months will be negative, so the only question is how long and deep will Europe’s recession be.

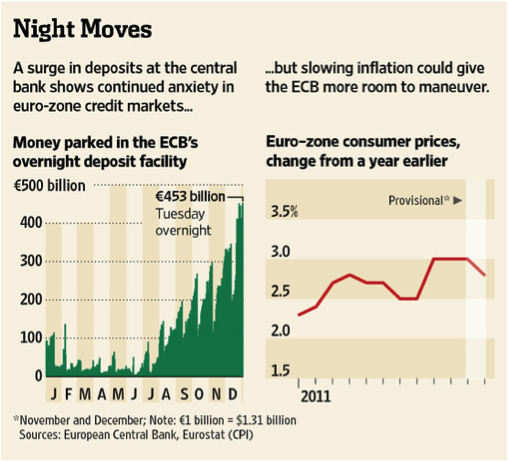

We think Europe’s recession has the potential to be worse than most U.S. strategists expect. As discussed in the November letter, U.S. banks provide 35% of total lending in the U.S. while European banks facilitate 80% of lending to corporations and consumers. This means the European economy is far more dependent on a functional banking system. Despite extraordinary measures by the European Central Bank, Europe’s banking system is on life support. In recent months, European banks faced increasing difficulty in rolling over existing debt, as U.S. money market funds significantly reduced their exposure. As liquidity dried up and the sovereign debt crisis intensified, banks in Europe curtailed lending to each other. In 2012, European banks have $900 billion of their own debt to roll over. Given the unwillingness of market participants to lend to banks, this refunding would be nearly impossible to accomplish, and risk another Lehman Brothers debacle. On December 21, the ECB offered European banks 3 year loans at 1%. A total of 529 jumped at the opportunity and borrowed $640 billion. Of the $640 billion, most of the new loans simply replaced old loans, so only $200 billion actually represented new money. The ECB will repeat this operation on February 28, which should help banks roll most of their coming debt in 2012.

It was hoped that this infusion of liquidity would encourage more lending by European banks. That’s not happening. Given the weakening in the European economy, banks are reluctant to increase lending in a weak economic environment, and demand for credit is falling from cautious consumers and businesses. Rather than making new loans, or lending to other banks, European banks have placed most of the money they received in the ECB’s overnight deposit facility. Banks have parked almost $600 billion with the ECB, up from $40 billion last June.

It was hoped that this infusion of liquidity would encourage more lending by European banks. That’s not happening. Given the weakening in the European economy, banks are reluctant to increase lending in a weak economic environment, and demand for credit is falling from cautious consumers and businesses. Rather than making new loans, or lending to other banks, European banks have placed most of the money they received in the ECB’s overnight deposit facility. Banks have parked almost $600 billion with the ECB, up from $40 billion last June.

It was also hoped that banks would borrow funds from the ECB at 1%, and then purchase sovereign bonds yielding more than 1%, pocketing the spread. This would help them increase earnings, add to capital, and bring down sovereign yields. This is the same strategy the Federal Reserve used in the early 1990’s, in the wake of the savings and loan crisis. It should encourage banks to buy their own country’s sovereign debt offerings, but we doubt a bank in France or Germany will step up to the plate and buy Italian or Greek debt, and risk a hit to their capital. They’ve already done than, and it is why many bank balance sheets are under pressure.

By June, banks in Europe must increase their core levels of capital by $115 billion. They can achieve this by either selling stock at depressed prices, selling assets to raise capital, or not renewing loans to existing clients. According to data compiled by Bloomberg, European lenders plan to meet the new capital rules by selling assets and not renewing credit lines. This does not bode well for European growth prospects. It is estimated that lending could drop by $1 trillion to $1.5 trillion in the next 18 months, which would amount to a 3% to 5% decline in credit as a percent of E.U. GDP. This process is already unfolding. According to the ECB, the annual growth rate in the volume in loans to households and companies in the 17 nation Eurozone fell to 1.7% in November from 2.7% in October.

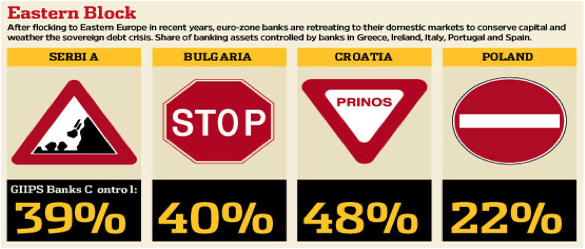

The contraction in lending by banks in Greece, Italy, Ireland, Portugal, and Spain to Eastern European countries will cause economic growth to slow in Serbia, Bulgaria, Croatia, and Poland, and likely result in a recession in Bulgaria and Croatia.

The contraction in lending by banks in Greece, Italy, Ireland, Portugal, and Spain to Eastern European countries will cause economic growth to slow in Serbia, Bulgaria, Croatia, and Poland, and likely result in a recession in Bulgaria and Croatia.

Fear that the sovereign debt crisis is far from over is causing investors in Europe to seek the safest holding place for their money, so they have been buying short term German bonds. Earlier this week, Germany auctioned six month bonds based on price, rather than yield. For the first time in history, investors accepted a negative return by paying more than $1000 for each bond, even though they will only receive $1000 in six months.

The total amount of sovereign debt maturing in 2012 exceeds $1 trillion. We doubt it will happen without a bump or two in the road, especially if the overall European economy is in recession, and the fundamentals of individual countries are really weak. It could be unsettling for the financial markets, if yields climb for the weak members of the E.U. as they are issuing new bonds. Although the ECB has repeatedly said they will not buy sovereign bonds, they are loaning money to banks, and then applying pressure on those banks to buy sovereign debt in their stead. Since last summer, the ECB has expanded its balance sheet from $700 billion to more than $1.2 trillion, an increase of more than 70%. They may not call it Quantitative Easing, since they are not buying bonds directly, but that’s effectively what the ECB is doing. The ECB’s mandate is to maintain price stability and keep inflation near 2%. On December 1, Mario Draghi, president of the ECB, noted that the mandate required the ECB to ensure price stability “in either direction”. This suggests that if the ECB felt that deflation was a serious threat it could use this as justification to buy government bonds directly, just like the Federal Reserve. This could prove a significant dynamic in the financial markets during 2012. If Europe’s economy does slow more than expected and yields in weak countries rise too much, equity markets will potentially suffer a 15% to 20% decline. This development could force the ECB’s hand, and lead them to announce that they would begin buying government bonds. That action may not spur economic growth, but the announcement would ignite a substantial rally in stock markets around the world. The volatility index (VIX) may be trading at 20.5, but that’s not likely to continue.

The total amount of sovereign debt maturing in 2012 exceeds $1 trillion. We doubt it will happen without a bump or two in the road, especially if the overall European economy is in recession, and the fundamentals of individual countries are really weak. It could be unsettling for the financial markets, if yields climb for the weak members of the E.U. as they are issuing new bonds. Although the ECB has repeatedly said they will not buy sovereign bonds, they are loaning money to banks, and then applying pressure on those banks to buy sovereign debt in their stead. Since last summer, the ECB has expanded its balance sheet from $700 billion to more than $1.2 trillion, an increase of more than 70%. They may not call it Quantitative Easing, since they are not buying bonds directly, but that’s effectively what the ECB is doing. The ECB’s mandate is to maintain price stability and keep inflation near 2%. On December 1, Mario Draghi, president of the ECB, noted that the mandate required the ECB to ensure price stability “in either direction”. This suggests that if the ECB felt that deflation was a serious threat it could use this as justification to buy government bonds directly, just like the Federal Reserve. This could prove a significant dynamic in the financial markets during 2012. If Europe’s economy does slow more than expected and yields in weak countries rise too much, equity markets will potentially suffer a 15% to 20% decline. This development could force the ECB’s hand, and lead them to announce that they would begin buying government bonds. That action may not spur economic growth, but the announcement would ignite a substantial rally in stock markets around the world. The volatility index (VIX) may be trading at 20.5, but that’s not likely to continue.

China

Europe is China’s largest export market, accounting for 20% of exports, followed by the U.S. The slowdown in Europe is starting to be reflected in China’s trade figures. In 2010, exports grew 31.3%, and were up 20.3% for all of 2011. However, by December, export growth had slowed markedly, and was only up 13% from a year ago. If the trade figures were adjusted for the 5.7% increase in the Yuans’s value in 2011 and inflation, the gain would have been cut in half.

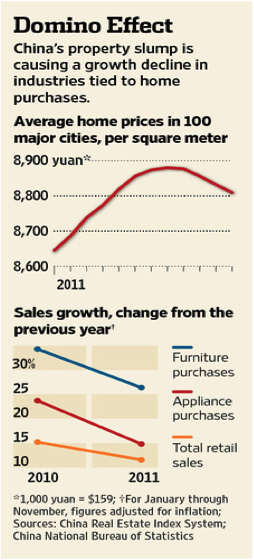

If slowing exports were China’s only challenge, the outlook would be brighter. Since 2008, Chinese bank lending and off-the-books lending totaled almost $10 trillion, according to the International Monetary Fund. That amounts to almost 200% of China’s GDP. To put that into perspective, prior to the real estate bubbles in Japan and the U.S., total loan growth amounted to just 50% of GDP. In 2010, gross fixed investment comprised 48.3% of GDP, more than 3 times the U.S.’s 15%. In addition to industrial capacity development, a good portion of lending was used in real estate construction of large cities. Ordos, which is located in Inner Mongolia, has averaged growth of 68.8% over the past four years, compared to 27.6% for China as a whole. It has a population of 1.6 million, but has 9.1 million square meters of property under construction. Many residents have two or three properties, and lots have seven or eight, according to a local real estate agent. With no one left to buy, prices have reportedly dropped 70% in the ‘ghost city’ of Kangbashi, a suburb of Ordos. Property sales have fallen 70% in the inland city of Changsa. When a developer slashed the price for an 850 square-foot Shanghai apartment from $173,000 to $124,000 in November, prior buyers almost rioted after being told they would not receive refunds. It appears the tipping point was reached last August when construction firms reported unsold inventory had reached $50 billion.

If slowing exports were China’s only challenge, the outlook would be brighter. Since 2008, Chinese bank lending and off-the-books lending totaled almost $10 trillion, according to the International Monetary Fund. That amounts to almost 200% of China’s GDP. To put that into perspective, prior to the real estate bubbles in Japan and the U.S., total loan growth amounted to just 50% of GDP. In 2010, gross fixed investment comprised 48.3% of GDP, more than 3 times the U.S.’s 15%. In addition to industrial capacity development, a good portion of lending was used in real estate construction of large cities. Ordos, which is located in Inner Mongolia, has averaged growth of 68.8% over the past four years, compared to 27.6% for China as a whole. It has a population of 1.6 million, but has 9.1 million square meters of property under construction. Many residents have two or three properties, and lots have seven or eight, according to a local real estate agent. With no one left to buy, prices have reportedly dropped 70% in the ‘ghost city’ of Kangbashi, a suburb of Ordos. Property sales have fallen 70% in the inland city of Changsa. When a developer slashed the price for an 850 square-foot Shanghai apartment from $173,000 to $124,000 in November, prior buyers almost rioted after being told they would not receive refunds. It appears the tipping point was reached last August when construction firms reported unsold inventory had reached $50 billion.

China’s banks were net sellers of foreign currency in October, which is very unusual. China’s trade surplus and normal inflows of direct investment means Chinese banks are always net buyers. Netting out the trade surplus from banks’ foreign exchange purchases provides an approximation of capital flows. If they are net sellers, in spite of a trade surplus, it means there was a net outflow of capital. In recent years a net outflow of capital has only happened twice. In May 2010 just as worries about a double dip were intensifying, and in August 2008, just before the financial crisis. In November, M2 money supply growth fell to 12.7%, the lowest in 10 years.

In coming months, the Peoples Bank of China will cut the reserve ratio a number of times and lower rates. This will likely give the Chinese stock market and global bourses a temporary lift. We think that should be enough to prevent a hard landing in 2012, and, at best, stabilize growth near 8%. But it will not lead to an acceleration of growth, which would ultimately prove disappointing for equity markets. However, if Europe’s recession proves deeper and more prolonged, 2013 could prove more challenging for China and the world economy.

Brazil

Brazil’s exports to China increased more than 18 times between 2000 and 2009. China is now Brazil’s largest trade partner, accounting for more than 17% of Brazil’s exports. In 2011, exports to China hit $44.3 billion, an increase of more than 43% over 2010. If China experiences an extended deceleration of growth, Brazil will be affected. The Brazilian government has cut its growth estimate for 2012 from 4.5% to 3.8%. Private sector economists only expect GDP to grow 3.0%.

Transparency at the Fed

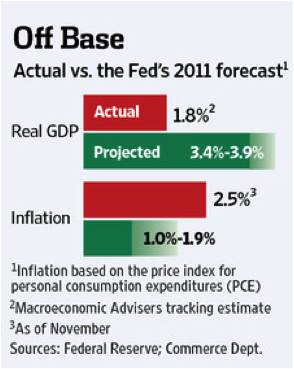

The Federal Reserve believes that publishing a range of interest rate forecasts by the five members of the Federal Open Market Committee, and the twelve regional district presidents will provide greater transparency of how the Fed operates and help market participants understand where monetary policy is headed. This new policy will be instituted at the Fed’s January 25, 2012 meeting. We appreciate the Fed’s attempt at allowing the masses to have a look behind the curtain, but its practical value seems limited since the Fed has been publishing a range for its estimate for GDP and inflation for years. The Fed’s 2011 forecast expected GDP to grow 3.4% to 3.9%, while inflation held in a range of 1.0% to 1.9%. Both forecasts proved off the mark by a factor of 50%. GDP only grew 1.8%, and inflation rose 2.5%. It is likely the new format will provide a wider range and prove equally inaccurate and unhelpful.

The Federal Reserve believes that publishing a range of interest rate forecasts by the five members of the Federal Open Market Committee, and the twelve regional district presidents will provide greater transparency of how the Fed operates and help market participants understand where monetary policy is headed. This new policy will be instituted at the Fed’s January 25, 2012 meeting. We appreciate the Fed’s attempt at allowing the masses to have a look behind the curtain, but its practical value seems limited since the Fed has been publishing a range for its estimate for GDP and inflation for years. The Fed’s 2011 forecast expected GDP to grow 3.4% to 3.9%, while inflation held in a range of 1.0% to 1.9%. Both forecasts proved off the mark by a factor of 50%. GDP only grew 1.8%, and inflation rose 2.5%. It is likely the new format will provide a wider range and prove equally inaccurate and unhelpful.

The Federal Reserve failed to see the housing crisis coming in 2006 and 2007, so publishing the views of the FOMC and regional presidents would have potentially led market participants to be even less concerned. In August 2007, the financial markets suffered what we referred to as a seismic event, which provided the first indication of how intertwined the financial markets were and the risks that interconnectedness implied. The following is from our September 2007 letter. “Throughout the Pacific Ocean there are sounding buoys to determine if a 100 foot tsunami traveling 500 miles per hour, or a 2 foot wading wave has developed after a large earthquake. The disruption that swept through credit markets worldwide in August was equivalent to an 8.4 magnitude earthquake. While seismologists know if a tsunami was created within a couple of hours, we won’t know for a number of months the full economic impact. But the displacements that took place leave no doubt that a significant seismic event occurred. In just seven days, T-bill yields plunged from 4.9% to 2.5%. In a month, the $2.2 trillion commercial paper market has contracted by more than 15%. Even as the ECB pushed well over $250 billion of liquidity into their banking system, the 90-day LIBOR rate jumped from 5.36% to 5.73%. In August, the issuance of junk bonds dropped by 93%, as the appetite for risk disappeared. This caused the spread between Treasury bonds and junk bonds to surge from 2.6% in June to 4.6% in less than six weeks.” However, at the Fed’s September 2007 meeting, New York Fed president Timothy Geithner said, “We just don’t see troubling signs yet of collateral damage, and we are not expecting much.” Alan Greenspan’s faith in the free market and belief that market participants would never pursue a path of self destruction is reflected in Kevin Marsh’s comment at the September 2007 meeting. “The capital markets are probably more profitable and more robust at this moment than they have ever been.” Clearly, Greenspan and Marsh had never seen the compensation plan of those at the major firms, and how much they were being rewarded for taking enormous risks, which were subsequently born by tax payers.

U.S. Economy

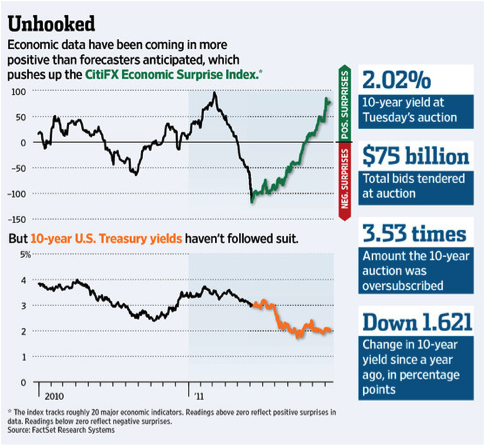

In recent months, economic reports have been better than expected. As a result, the CitiFX Economic Surprise Index has been climbing, and is now near the high it recorded in March 2011, just before the stock market topped last year. We think that’s about to change and potentially coincide with another market high. U.S. exports accounted for 13.4% of GDP in the third quarter, compared to 9.6% a decade earlier. If the global economy slows as we expect, exports will add less to domestic growth in coming quarters. The Dollar has rallied by 10% since August, which makes our exports more expensive, and will pressure U.S. companies that derive 40% to 60% of their sales from overseas. As we have discussed previously, the investment tax credit, which allows businesses to write off 100% of an investment, undoubtedly pulled investment spending forward into the last half of 2011 from the first half of 2012. This clearly contributed to the improvement over the last few months in the ISM manufacturing index. As an example, if the tax credit boosted investment from a 2% growth rate without the tax credit, to an increase of 3%, investment could fall to 1.0%-1.5% in the first half of 2012.

In recent months, economic reports have been better than expected. As a result, the CitiFX Economic Surprise Index has been climbing, and is now near the high it recorded in March 2011, just before the stock market topped last year. We think that’s about to change and potentially coincide with another market high. U.S. exports accounted for 13.4% of GDP in the third quarter, compared to 9.6% a decade earlier. If the global economy slows as we expect, exports will add less to domestic growth in coming quarters. The Dollar has rallied by 10% since August, which makes our exports more expensive, and will pressure U.S. companies that derive 40% to 60% of their sales from overseas. As we have discussed previously, the investment tax credit, which allows businesses to write off 100% of an investment, undoubtedly pulled investment spending forward into the last half of 2011 from the first half of 2012. This clearly contributed to the improvement over the last few months in the ISM manufacturing index. As an example, if the tax credit boosted investment from a 2% growth rate without the tax credit, to an increase of 3%, investment could fall to 1.0%-1.5% in the first half of 2012.

The 200,000 gain in jobs reported for December is a positive, as is the 2.7% increase in earnings. However, 42,000 of the jobs were related to warehouse-delivery type jobs (internet warehouses and UPS) which are likely to be reversed come January, since that’s what happened in December 2010 / January 2011. Despite the improvement in earnings, wages are still lagging behind the cost of living. According to Sentier Research, real median annual household income has dropped 5.1% since the end of the recession

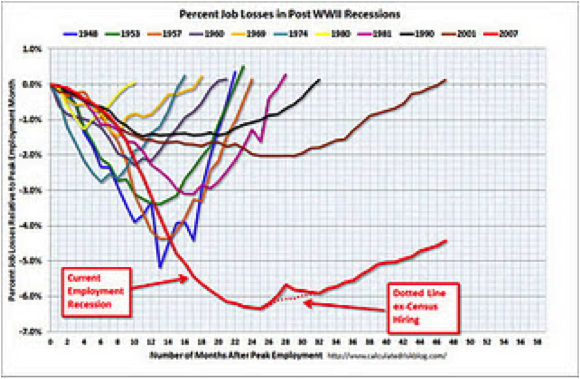

in June 2009, versus the 3.2% decline that occurred during the recession. This means half of all consumers have fallen further beyond during the recovery than during the recession. Wow.  The current recovery in jobs is the weakest since World War II, as the chart nearby shows. Retail sales for the month of December were fairly muted despite all the hype surrounding Black Friday. This surprised most retail analysts who were forecasting gains of 5% to 6% in holiday sales. In our October letter we explained why we thought those forecasts were too optimistic. “Traditionally, retailers begin taking delivery of holiday merchandise by late October. For this to happen, orders that are placed for goods produced overseas begin to arrive at the five busiest ports in the United Sates during August and September. The rush of holiday merchandise usually causes a spike in container volume at the ports. There was no spike in shipments in August and September at any of the five ports. In fact, each of the five largest ports reported declines from 2010 levels.” Many retailers were only able to goose their holiday sales by offering significant discounts to lure shoppers into stores, which certainly eroded profit margins. This lackluster showing underscores that most consumers have a keen eye for bargains, so they can make every paycheck stretch as far as possible.

The current recovery in jobs is the weakest since World War II, as the chart nearby shows. Retail sales for the month of December were fairly muted despite all the hype surrounding Black Friday. This surprised most retail analysts who were forecasting gains of 5% to 6% in holiday sales. In our October letter we explained why we thought those forecasts were too optimistic. “Traditionally, retailers begin taking delivery of holiday merchandise by late October. For this to happen, orders that are placed for goods produced overseas begin to arrive at the five busiest ports in the United Sates during August and September. The rush of holiday merchandise usually causes a spike in container volume at the ports. There was no spike in shipments in August and September at any of the five ports. In fact, each of the five largest ports reported declines from 2010 levels.” Many retailers were only able to goose their holiday sales by offering significant discounts to lure shoppers into stores, which certainly eroded profit margins. This lackluster showing underscores that most consumers have a keen eye for bargains, so they can make every paycheck stretch as far as possible.

If we’re right, the recent improvement in various economic data points is merely setting the stage for them to roll over, as the impact of Europe’s recession is felt around the world and in the U.S. Whether the threat of recession is real is secondary. Just the hint that the U.S. is slowing will raise concerns that a double dip might happen, and should be enough to cause the stock market to suffer. The comments in recent weeks by a number of Fed governors about the need for the Fed to do more to lower unemployment, also suggests the threat from Europe is greater than most strategists realize. We have no doubt the Fed has QE3 waiting in the wings, and will execute its plan, if things get really ugly in Europe and the S&P drops below 1158.

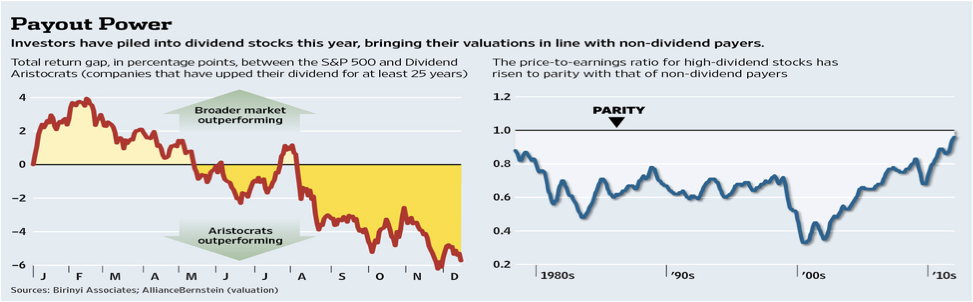

Stocks – Wall Street loves to promote investment themes, which at their outset make sense and have value. But like all good things, they become over done, and then undone when things change. Over the last year the most dominant theme has been to buy stocks paying solid dividends of 3% or more. Compared to the 10-year Treasury yield of 2%, an increase of 50% or more in annual income has value. Since 1978, dividend paying stocks consistently underperformed non-dividend payers, which were more focused on growth than dividends. The period of relative weakness ended in 2000, at the peak of the dot.com mania. Since then, dividend paying stocks have been gaining in relative performance, and now sport the highest relative P/E ratio in more than 30 years. A recent study by AllianceBerstein ranked 650 large cap stocks by their dividends, and grouped them into quintiles. Currently, the premium of high-dividend payers over low-payers is the highest in 40 years. This fact alone does not mean this trade cannot continue to work, but a measure of caution is advised based on contrary opinion. We suspect this trade has attracted a lot of conservative money that is focused more on the income than the potential downside risk. If the stock market experiences another 20% decline in the next year, a dividend of 3% won’t provide much solace if one’s nest egg has shrunk by 17%.

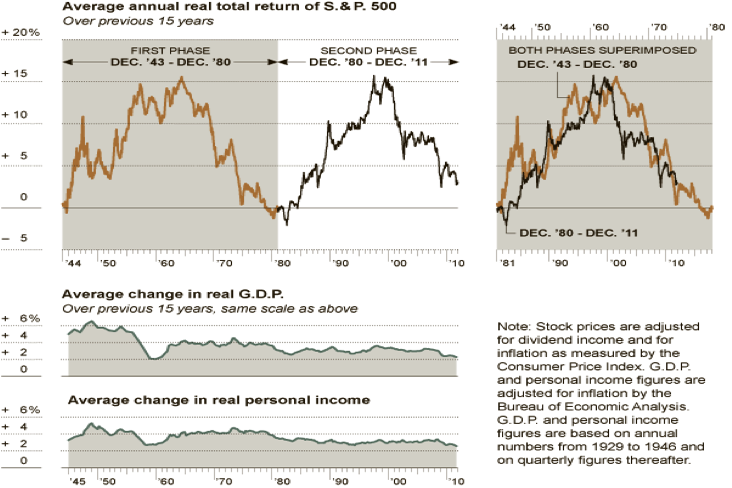

Over the last 80 years the stock market has swung like a pendulum between undervaluation and over valuation on a 15 year rate of change based on returns. The total length of time between peaks and valleys is about 38-39 years. After peaking in 1929, the next peak occurred in 1968, and then again in 2007. The 15 year return valuation low in 1943 was repeated in 1982, and suggests the next secular bull market may not begin until 2020-2021. The next 8 to 10 years could be challenging. Central banks will continue to inject liquidity every time their domestic or the global economy falters, due to the unwinding of financial leverage and over indebtedness of governments and consumers. If the central banks are successful, stock markets will fluctuate wildy, as periods of economic weakness or contraction cause sharp sell offs, and monetary accommodation ignites big rallies. Central bankers are confronting the largest credit bubble in history, and there is no guarantee they can prevent a tidal wave of defaults from sinking the global economy, no matter how much they expand their balance sheets.

The next 8 to 10 years could be challenging. Central banks will continue to inject liquidity every time their domestic or the global economy falters, due to the unwinding of financial leverage and over indebtedness of governments and consumers. If the central banks are successful, stock markets will fluctuate wildy, as periods of economic weakness or contraction cause sharp sell offs, and monetary accommodation ignites big rallies. Central bankers are confronting the largest credit bubble in history, and there is no guarantee they can prevent a tidal wave of defaults from sinking the global economy, no matter how much they expand their balance sheets.

As we noted in our December letter, “As long as the S&P holds above 1190, there is still the potential for the S&P to push above the late October high at 1292. Investors should consider allocating a small portion of their portfolio to the Prudent Bear fund or the inverse S&P 500 ETF SH, especially if the S&P climbs above 1292. Both would rise in value as the market declines.” The S&P did climb above 1292 this week when it exceeded 1296, so the market is at an interesting juncture for a number of reasons. Various measures of sentiment reflect a surge of bullishness, in response to better economic reports and market rally. Ironically, the S&P is no higher than it was at the October 28 peak, so the market’s net progress has been nil. Internally, the market is overbought, and the rally has occurred on very light volume, aided by an absence of negative news. As we have discussed, low volume rallies are vulnerable should any negative news appear and cause a pick-up in selling pressure.

The S&P has approached resistance, as marked by the trend line connecting the lows in March and June, and the high last October. Pattern analysis suggests this could be an important high, since the A B C (Most Bearish) from the October low would suggest the market is poised to decline below the October low in the next few months, as a Greek default triggers another financial dislocation. We think it more likely that the current high will be followed by a decline to near or below 1158, and then be followed by a rally that would be equal in length to the 217 point rally from the October low at 1075, if the ECB becomes more aggressive in counteracting Europe’s recession. (Less Bearish) The least bearish scenario is for a modest decline that holds the wedge line of support between 1235 and 1248, which is followed by a dynamic push above 1320 on much higher volume. The .786 retracement of the decline from 1370-1075 is 1307. The initial rally from 1158 topped at 1267. Adding 109 points to the 1202 low targets 1311. Next week is option expiration, so the S&P may be able to grind up to 1307-1311. But the common thread in the above scenarios is that the market is near a high of some significance and vulnerable to a decline. Shorts established when the S&P exceeded 1292 should use a close above 1320 as a stop.

Bonds – In our November letter we suggested buying TLT, which is the ETF that mirrors the yield on the 20-year Treasury bond. It traded as high as $125.03 on October 4, just as the stock market was making its low. We think it will trade above $125.03. Use a close below $115.80 as a stop. Sell half if it trades above $125.03, and raise the stop to $117.50.

Dollar – In our May letter we recommended going long the Dollar via its ETF (UUP) at $21.56, and in our July 31 Special Update, we suggested adding to the UUP position below $20.91. A close above $22.62 should constitute a breakout, and set the stage for a rally above $24.00 in coming months. Use a close below $21.90 as a stop.

Gold – Since gold topped on September 6 at $1923, we have expected gold to decline below the September low of $1535.00, which it did on December 29. We recommend selling 65% of the position purchased at $154.00 on the opening on December 30, which was $155.48. We wanted to buy one-third of the GLD position back at $145.00, and another one-third below $140.00, but the low was $148.27. Sell on the opening of January 17, and repurchase one-third at $152.20, using $148.30 as a stop.

What's been said:

Discussions found on the web: