Confusion About the Financial Crisis Won’t Die

Explanations driven by ideology muddle rather than clarify.

Bloomberg, January 28, 2016

Once more unto the breach, dear friends, once more.

Having slogged through several years of research on the many and complex causes of the financial crisis, I take it personally when people try to rewrite history and ignore what actually drove the events that led to the collapse.

That is our charge today, in response to the rather perplexing claim that the Federal Reserve caused the crisis — not because former Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan irresponsibly kept rates low for too long, but rather because the Fed raised them.

This is the proposition offered in a New York Times op-ed by David Beckworth of the Mercatus Center and Ramesh Ponnuru of the American Enterprise Institute and a Bloomberg View columnist.

Before we delve into details, a preface: We have spent a good deal of time explaining how and why complex things are easy to misunderstand. There is rarely if ever a single factor that drives complex systems such as the economy or markets; the real world isn’t that neat and simple. As philosopher David Hume once explained, causation is a much more nuanced thing; correlation can be confusing. There also is the issue of some folks who feel compelled tomisrepresent what caused the crisis, as it helps rationalize their own cognitive dissonance.

We and others have discussed this in the context of the movie “The Big Short.” That is the leaping-off point for Beckworth and Ponnuru article.

To make the claim as the authors do that “The bursting of the housing bubble was the primary cause of a financial crisis” is to confuse cause and effect, to ignore a wealth of other well-documented factors,and to marry a straw-man argument with an oversimplified explanation for what happened. Just as the collapse of Lehman Brothers didn’t causethe crisis, neither did the bursting of the housing bubble. Both of these events were the result of many factors in a complex chain. These two events were the result of the crisis, not its main cause.

Instead, the argument Beckworth and Ponnuru make is “that the Federal Reserve caused the crisis by tightening monetary policy in 2008.” They also say that the “housing bust started in early 2006, more than two years before the economic crisis.” Both of these assertions are incorrect, for the seeds of the bust were planted long before. What’s more, the Fed didn’t tighten in 2008; it cut rates seven times.

Housing operates on a lag, and up cycles end with volume declining first, followed by prices a year or so later (our Masters in Business conversation this coming weekend with residential real estate expert Jonathan Miller discusses this exact issue). Volume peaked in 2005, but prices kept rising, peaking in 2006. It’s as if no one told the housing zombie it was dead, and its own momentum — and buyer psychology — kept on chugging. Volume topped in 2005, followed by prices in 2006, at which time the whole sector started declining.

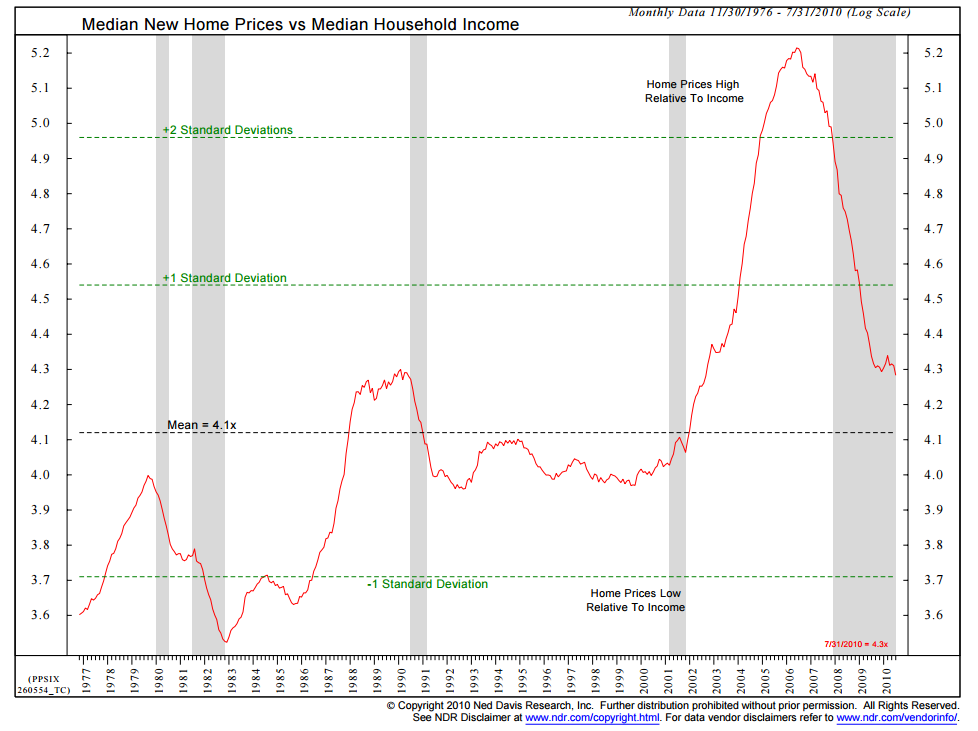

But if you want to track where the housing bust began, you need to look at the relationship of home prices to other important metrics. My favorite is median home price to income, as it tells you what buyers can actually afford. We can also look at costs of rent versus costs of ownership, or the market value of all of the homes in the country relative to gross domestic product. All of these metrics tell us exactly how realistic prices are, meaning can the buyers actually afford them.

As you can see from the chart below, the ratio of home prices to income began to tick up in the early 2000s. By 2002, it was approaching its 1980s highs. It was a standard deviation away from the norm by 2004, and it reached at 2 1/2 times the norm in 2005. Housing, as a few of us observed long before the financial crisis bloomed, was a debacle about to happen.

The housing boom drove employment in construction, mortgage brokerage, home furnishings and durable goods. We even had a bull market in real-estate agents. People pulled cash out of their homes at furious rates to fund renovations at first, then big-screen televisions, automobiles and vacations. The broader way to understand this is that wages were stagnant, inflation was starting to rise and rather than accept a drop in living standards, people used home equity to maintain consumption.

This is more complex, multifaceted and nuanced than the notion that Fed rate increases tanked the economy.

Also note that inflation, which the authors dismiss, was showing unsettling signs of picking up. And there were data points that were positively frightening, particularly in commodities. Oil had risen from $20 a barrel in 2002 to more than $75 in 2006 and was on its way to more than $140; milk was more than $6 a gallon, and beef prices were skyrocketing. The dollar had declined almost 42 percent from 2001 to 2008, making every commodity quoted in dollars pricey.

So it isn’t really appropriate to dismiss the Fed’s concerns about inflation out of hand. This isn’t a minor oversight or omission in Beckworth and Ponnuru’s argument, but a fundamental error.

Other analytical errors also compromise their argument. Was the housing decline caused by the “uncertainty about the value of bonds backed by subprime mortgages” as the authors say? If you believe that, you must ignore the simple fact these mortgages were going into default in record numbers, dragging down the values of those bonds. In many cases, those bonds ended up being worth pennies on the dollar.

The “uncertainty” argument here reflects, as it does in so many other cases, a basic misunderstanding of mathematics. We know the data set of possible outcomes for those bonds — it ranges from zero to full face value, including all of the increments in between. That isn’t properly defined as “uncertainty”; it is merely an unknown. There is a huge difference between the two.

Another analytical error can be found in the sentence: “According to Gary Gorton, an economist at Yale, roughly 6 percent of banking assets were tied to subprime mortgages in 2007.”

This is analogous to an oncologist telling a patient that a malignant tumor is less than 6 percent of body mass.

The defaulting subprime securities were indeed malignant, and they metastasized throughout the financial system. The subprime cancer almost killed Bear Stearns before it was bailed out and it bankrupted Lehman Brothers. The financial disease quickly spread to American International Group, Citigroup, Merrill Lynch, Countrywide, Bank of America, Wachovia, Washington Mutual and Morgan Stanley. The only major banks that escaped relatively unscathed were Wells Fargo (which acquired Wachovia), and JPMorgan Chase (which acquired Bear Stearns and Washington Mutual).

The Fed — among many other players in this sordid affair — bears some responsibility for the crisis. But its biggest error, aside from refusing to rein in reckless mortgage lenders, was something different than what Beckworth and Ponnuru describe. Its error was taking rates too low and leaving them there for too long in the early and mid-2000s. Combatting inflation is half of the Fed’s dual mandate (the other is maximizing employment). To blame the central bank for raising rates to ward off inflation is to fundamentally misunderstand the Fed’s role, the importance of price stability and the basic rules of causation-to-data theory.

As long as pundits persist in explaining the financial crisis through the lens of ideology, the harder it will be to implement the measures needed to prevent the next one.

~~~

I originally published this at Bloomberg, January 28, 2016. All of my Bloomberg columns can be found here and here.