Paul Brodsky & Lee Quaintance run QB Partners, a private macro-oriented investment fund based in New York.

~~~

QB ASSET MANAGEMENT

May 2009

The New Yorker magazine has maintained long preeminence among literate types by wrapping usually good writing in an old-world sensibility. While one may agree or disagree with its varying points of view, there is no doubt that the cascade of usually well-chosen words merely seek to rise to the level of profundity its cartoons seem to express so easily.

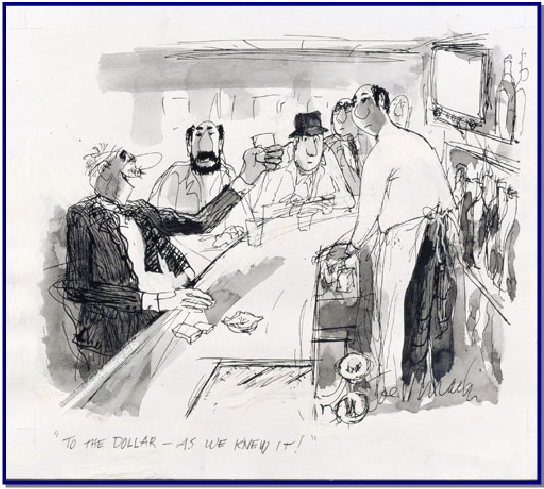

We found the one below while visiting the “ON THE MONEY” exhibit at the Morgan Library and Museum (January 23 to May 24). It was drawn by Joe Mirachi and published in March 1980 during a period of massive price inflation and rising interest rates (brought about by years of massive government produced monetary inflation). Mr. Mirachi’s barflies knew that such highfalutin terms were only fancy expressions for dollar devaluation. “TO THE DOLLAR – AS WE KNEW IT!” Indeed.

Or consider Lee Lorenz’s depiction of the dubious nature of government statistics (on the following page). This cartoon appeared in the New Yorker in March 1976, almost two decades before the Bureau of Labor Statistics began playing with the consumer price index by subjectively substituting, re-weighting and placing a hedonic value on consumer goods and services. As the cartoon’s subjects imply, (and as our essay last month proclaimed), some things never change.

We were so inspired by the unthreatening manner in which these gadflies are able to expose economic elephants in the room that we felt obliged to give it a shot. Alas, our crayons failed us. Lacking the necessary talent (and imagination) to even attempt the creation of poignant cartoons, we instead sought to assassinate the high art of literary fiction. Mr. Updike, we are sorry you’re gone but happy you won’t see this:

The Briefing

bad fiction

The narrow hallway had been going on endlessly, curving gradually down and to the left like a giant underground corkscrew or one of those ramps we drive around in parking garages. At last we were coming to a door, another 100 yards or so down. My mysterious escorts and I had been walking at a pretty good clip for a long time, descending deeper and deeper. We hadn’t passed any doors since we entered the hallway and it occurred to me that the entire tunnel’s function was to arrive at the one we were now approaching. We must be, what, 100 feet below the basement of the White House by now?

The only sounds over the last ten minutes were our footsteps and the occasional soft sound of fresh air flowing through small vents in the floor. I had grown accustomed to mysterious people walking behind me, usually in some sort of security detail. But these were older, patrician men dressed in classic business suits and without the tell-tale earpieces of security guards. They had appeared in the room off the White House kitchen suddenly and, it seemed, from nowhere. Each gave me only a faint acknowledgment of my presence, which was unusual, though I must admit refreshing. These four men were the only ones with me. Even Johnny, my newly assigned “body man” was given the morning off until I went back to the transition team’s hotel.

A Marine opened the door and we walked into a smallish, rectangular room. Was this where Dick Cheney went on 9/11? The room was comfortably appointed, casual. It was designed for people to talk – two long couches facing each other with two chairs on either end. There was a small table against the wall behind one of the couches and a desk behind the other couch. Yet there was nothing on the desk. In fact, there were no design accessories anywhere in the room – no pictures on the wall, American flags, rugs or potted plants.

http://www.ftd.de/lifestyle/outofoffice/:Out-of-Office-Wirtschaft-als-Karikatur/464548.html?imgpopup=2; Cartoonbank.com; The New Yorker; Lee Lorenz; 1976.

A man in his late sixties sat in the far chair, his right knee crossed elegantly over his thigh, reading a brief and massaging a temple. He didn’t rise from his chair as we entered, remaining deeply involved in his report. I wasn’t used to that behavior. Ever since I was elected to the Senate people tended to stop what they were doing when I walked into a room. He put up an index finger to signal he was almost through. The four strangers that ushered me down sat on the couches.

I stood behind the remaining chair, benevolently I thought, to give the man a chance to gather his senses and use proper protocol. This treatment wasn’t as refreshing as it was a moment ago. I thought I could make out a door behind his chair; flush with the wall and without a handle. After a few moments he put his paper into a briefcase, took off his reading glasses, rose out of his chair and came over with an extended hand.

“Mr. President-Elect, I’m sorry to have kept you waiting but I find if I don’t complete a brief in one-fell swoop then I have a tendency to lose its context.” His accent sounded as though he came from somewhere in the Atlantic Ocean, some words sounding American and others British. Not quite English; a second-generation Scot?

We shook hands and he smiled warmly. “Please, please sit down so we can start. I don’t want to take too much of your time today. I understand you have a busy afternoon. The President was kind enough to give us this wretched cave this morning. I guess it’s a place where we can be sure that our acquaintance and our words remain our own.”

I sat down and crossed my legs, reminding myself that I was about to be the President of the United States, the leader of the free world, and that everyone would soon answer to me. I would adopt that attitude for this meeting, if only to survive it.

“Mr. Jones,” he began, “my name is Alex Hamilton. I have no political affiliation, I am not in government and I have no official title within any business in the private sector. I sit on no corporate boards, though I do participate in several charitable causes. I don’t appear on TV or in magazines. I make no lists. I live a very quiet life.”

“Yet, the President invites me here under the public guise of a friendly transitional lunch so I can meet you and your colleagues here in his secret cave. You must be the Great Wizard.”

Hamilton feigned an ignominious chuckle. “I, and a few others around the country and around the world, care deeply about maintaining a peaceful, prosperous existence. Together we want to ensure that the maximum number of people are fed, clothed, housed and, above all else, that they remain calm. We also want to ensure that the world’s resources are distributed to this end and that there is, more or less, an equitable distribution of rewards for doing so.”

“Do you mean…”

“Let me finish, please. We see no distinction between public and private sectors in our representative economies and no true distinction between our myriad political parties or philosophies. Indeed, we see fewer and fewer conflicting agendas that divide our nations. We see the world in international terms. We have common goals, Mr. Jones, and in fact over the last couple of generations most of the world’s peoples’ have been benefiting from the pursuit of them.

“Are you talking about a world government here?”

“That has such official overtones, like there is some secret structure with codes and bylaws and conference tables and evil bad guys looking to take over the world. No, that is not what I’m talking about. I’m telling you that, at the end of the day, a growing number of nations’ wealth and standards-of-living are being negotiated based on their productive capacities, resources and contributions to world peace.”

“That sounds like global socialism.”

“Your Majesty, my voyage will not only forge a new route to the spices of the East, but it will also increase the productivity of your fleet by 3.2 percent.”

“If it satisfies the lawyer in you to find an acceptable label for the world’s system of social organization, then fine, you may call it whatever you like. However, I would remind you that there isn’t, and never has been, a sustainable true capitalistic democracy. The closest the world has come is the US, which in reality has been…oh I suppose a social republic for quite awhile now.”

“I thought we practiced capitalism here?”

“And that’s a view we would like the public to hold onto a little longer. As you know, capital is nothing more than sustainable resources and the means of its production. Capitalism is promoting the production of it through free enterprise – reward for production and punishment for failing to produce. The US hasn’t produced much industry for a while. Nor have we punished failure, other than making those who don’t succeed bear witness to those that do. Other than an occasional invention or innovation, we mostly produce money, debt really, which we float and export in return for other nations’ resources and production capabilities.

“I see. So, if I’m to go along with this, the impact on my US domestic and foreign policies would be substantial.”

Two of the men on the couches shift their legs. Hamilton is quiet, his face passive.

One of the men on a couch adjusts his glasses and speaks. “Mr. President-Elect, I think you’ll agree that what Mr. Hamilton has described is the basis for your domestic and foreign policies – their reasons for being. The money we produce provides the result that all your policies should seek to achieve. The point here is that your administration only has to maintain our current form of capitalism…our non-industrial capitalism, our monetary-centric economic regime.”

Another man on the other couch spoke up. “Mr. Jones, in two months, God willing, you will be the President of the United States. The people chose you as their leader and that makes them feel good, like they are in control of their lives. Half of them are on your side philosophically and all of them want you to make their lives better. I have no doubt that if you adhere to your political philosophies, whatever they may be, and every now and then compromise with the other side, then you and your family will gain the respect of the people. You will be a fine President and, someday, a respected past President – a member of the world’s most exclusive club. I trust you will have made the world a better place. Your great grandchildren will be admitted to Harvard. And you will not have compromised your ideals.”

Something didn’t seem right. “So, if natural parliamentary checks and balances shouldn’t allow our dollar-based global monetary regime to lose its hegemony – or allow the US to lose its pre-eminent status in the world – why would your secret…group here need to brief me at all?”

Hamilton uncrossed his legs and leaned forward. “In the event, Mr. Jones, that systems begin to break down – either potentially lethal foreign or domestic rogue entities agitate for change or if the global economy becomes… temporarily unworkable, you need to know that we are here and that we have the power to resolve such crises through channels that might not be obvious.”

I leaned back in my chair, not having realized I was sitting on the edge of it. I took a deep breath and looked at the five men, who were staring at me.

I turned to the leader. “How would you do that, Alex?”

Hamilton smiled and leaned down to buff a shoe with a finger. He looked at one of the men who hadn’t spoken yet. It was his cue.

“When people or countries go off the reservation it’s either out of some sense of idealism or because they feel cheated. When this happens, Mr. Jones, we create money, as much as it takes, and then we send it where it’s needed. That usually works, even with ideologues.”

My college studies and political career focused on policy, domestic and foreign. I had developed well thought-out platforms on the optimal role of government and the equitable distribution of capital. I developed cogent and consistent platforms for economic, trade and tax policies, optimal budget appropriations, workable social policies and the use of diplomacy and military intervention. I felt strongly that my views were superior to those on the other side of the aisle. Speaking with these mysterious men suddenly made all that seem trivial.

“So just printing money makes all the problems go away? That’s it? Are you guys serious?”

Hamilton was quick to respond. “It’s been excruciatingly difficult getting to this point. There was a lot of conventional, provincial dogma across borders that had to be overturned. Russia, China, India, the EU, the Middle East – it took generations. You’re lucky you weren’t elected in the early twentieth century. Even after World War II we didn’t have a common understanding with some of the necessary economies. Now we do, Mr. Jones, and we should all be grateful.”

“I see. What about terrorism and war? What about the authoritarian capitalism?”

The fourth man on the couch who hadn’t spoken yet cleared his throat. “Mr. Jones, when Mr. Hamilton spoke about our money being our biggest resource, he wasn’t merely talking about having turned paper into capital. We were able to do this because we have the world’s largest and most sophisticated army. We don’t use our military to invade for natural resources or treasure, or to extort other economies, though frankly we could; we use it to protect the flow of other’s resources around the world, including to us. Our true capital, therefore – the benefit we offer world economies – is the protection our allied military power provides them. Our price for that protection is that the world accepts our paper currency.”

“We run a protection racket?”

I didn’t mean to sound so crass or idealistic and I was glad when he ignored me and continued speaking.

“Now put recent events into this monetary context, Mr. Jones, and they should all begin to make sense. Terrorists attacks, state-sponsored invasions, money flows, trade alliances…all have a unifying theme – the reconciliation of global resources…bringing varied interests back into balance…maintaining a certain…equilibrium.”

I gave my best empathetic look, sharpened over many months of campaigning. He continued.

“At the end of the day people and their leaders want fairness and sustainability – of resources and of wealth. Most often terrorist threats and actions are politically motivated; rarely are they are borne from genuine oppression. Terrorism seeks fairness. As for war – it usually seeks resources, a land grab if you will. It occurs when negotiation fails. And as for authoritarian capitalism…as I’m sure you know it is merely a euphemism for a legal oligopoly defended by the state. It is concentrated wealth which, if truth be told, is what would happen to the US economy if it had true democratic capitalism. A few of us would grab most of the resources, as we did before the anti-trust era in the thirties.”

I felt like Peter Finch’s character in the movie “Broadcast News,” getting the lecture about how the media business was not supposed to provide real news, but a public diversion, and at a price. I wasn’t going to give up.

“Okay, so we make the world’s reserve currency and we can distribute any amount of it anywhere we like, anytime we like.”

“Yes” they all murmured.

“And we pay our military with that currency…”

http://www.thirteen.org/sundayarts/blog/visual-art/the-morgan%E2%80%94laugh-to-keep-from-crying; The New Yorker; Dana Fradon; September 21, 1992

“Yes,” Hamilton agreed; “and, as it turns out, every other country effectively pays their militaries in dollars or currencies linked to the dollar’s value.”

“So then dollars are at the center of it all.”

Hamilton nodded. “Protecting the hegemony of the dollar is the key to global peace and prosperity. Everything else is secondary.”

“And there’s no limit to how much we can create?”

The room fell silent. Finally, Hamilton spoke.

“There might be a limit, under certain circumstances. The dollar and all global currencies have no fixed backing, no fixed exchange rate. They are not stores of value. We would have a problem if we print so much money that it forces other nations to print in kind, causing a general mistrust of the global fiat monetary system.”

Another man spoke. “But we don’t think that will happen. The only thing that matters in most countries is that businesses, consumers, governments, and militaries remain willing to accept the paper money as units of account and as means of exchange. They’ve been trained, if you will, over the last forty years not to expect their money to be stores of value.”

Another man piped in. “Everything remains copasetic if all major nations – all major currencies – comply.”

I felt like a schoolboy. “So that’s the deal, then? Make sure the US stays on good terms with its major trade partners? Make sure that we all continue exchanging our currencies and that the people continue to want them?”

Alex Hamilton smiled. “Yes, Mr. Jones. That’s the key. Foreign or domestic policies that threaten the global fiat monetary system should not be pursued or tolerated.”

“But what about private actors? What can global governments do about private capital holders exchanging their paper currencies for, say, gold or natural resources?”

Hamilton leaned forward. “That’s a fair question and one that requires a fairly complex answer. First, we can manage the generally-accepted price of gold on the global markets so that its rising value does not appear to imply the corollary – that paper money is losing its value.”

“How?”

He ignored me and continued. “Second, populations and governments in the developed world are already highly indebted. There are very few net creditors. So, most of the world has to pay back their obligations with the paper money we provide them. If a large enough contingent doesn’t behave the way we want, we can either drain currency from the system, forcing them into default….”

“Who would get those assets?”

“Creditors, Mr. Jones; banks and bond holders would get them. But that isn’t what we want. We don’t want to drain reserves permanently because we’d have deflation and social chaos. As I was about to say we would rather create the money for all to see, but not distribute it until the time is right for borrowers to comply.”

“Comply with what?”

“Acceptable terms of commerce and trade, Mr. Jones.”

“Acceptable to whom?”

“Acceptable to US banking and military interests, first and to other global interests second. Remember, this is our capital base. These are our sustainable resources.

Silence fell upon the room. Hamilton spoke softly.

“Mr. Jones, the Fed has a monopoly on printing the world’s money and the largest global banks are members of an oligopoly with rights to distribute it. This is our form of authoritarian capitalism, as you might say. Together they are the creditors to the world’s wealth – its natural resources and means of production – because the dollar is the world’s reserve currency.”

“So we’re all working for the banks because we all owe them money.”

Hamilton nodded. “At the end of the day, most people in all countries come into the world with nothing and would generally be happy leaving the world with nothing as long as they don’t miss a meal in the interim. We give them that and charge them for it. They borrow from us to obtain food, warmth, shelter, education and a decent lifestyle and then they give it back to us. By printing new money we inflate away the value of their property and it returns to the banking system where it may be leant again to the next generation. Our children will have to work and stay busy – too busy we hope to rise up.”

“So you work for the banks, Hamilton?”

“We all work for the banks, dear man. We, all of us, lease our resources. We don’t pass them down to our children to squander, the way monarchies did, or leave our resources in bearer form so that any army can waltz in and pillage them. The US and most large economies have settled on being leasehold states, Mr. Jones. The banks are the one constant. They keep us in debt, which keeps us safe.”

“Jeez!” was all I could come up with. Then, “they keep all of us in debt?”

http://www.calbar.ca.gov/calbar/pdfs/sections/agendas/trusts_2007-11-03.pdf; The New Yorker; Cartoonbank.com; Lee Lorenz; September, 22 1997

Alex Hamilton smirked and raised an eyebrow. “Well…most of us my dear man, most of us.”

Suddenly there was a harsh ringing in my ears that grew louder and louder. A fog slowly lifted and I opened my eyes. It was all a dream! I turned the alarm off and sat up in bed. I was not going to be President. There was no tunnel below the White House, no secret room, no five wise men, no global conspiracy, no “common goals”, no secret cabal that ran the world. There was only waking the kids for school, getting money from the ATM and going to work. Whew!

Paul Brodsky

pbrodsky@qbamco.com

Lee Quaintance

lquaint@qbamco.com

What's been said:

Discussions found on the web: