I try to find people to read who a) I disagree with 2) respect their methodology. It refines my arguments, and clarifies my thinking.

Doug Kass is one such thinker. So too are Jeff Saut of Raymond James, and Peter Boockvar of Miller Tabak (Peter publishes the very fine Macro Notes blog here on TBP). I am a big fan of both of them, so when Saut quotes Boockvar about the lack of deflation, it forces me to think carefully about my position.

Here’s Jeff channeling Peter:

“With Treasury bond yields at or near historically low levels on one hand but with commodity prices near 8 month highs, and with the personal feeling that outside of a home, a computer and a flat screen tv, the cost of living seems to only go higher on the other hand, here is another perspective on the inflation/deflation debate. Since June 1981 when Volker started to lower interest rates from 20% as high inflation rates started to fall, the absolute level of CPI rose 142% to the high in July ‘08 (90.5 to 217). Deflation is defined as a decrease in the general price level of goods and services but to quantify the current fall in prices, the CPI has fallen just 1% from its all time high.”

The Treasury rates certainly argue against inflation. But let’s look at two other factors, CRB and CPI.

The CRB is a measure of commodities, priced in dollars. Commodities rise in price primarily due to three factors. The classic inflationary reason is an increase in demand. Or, you can have a decrease in supply (or some combination of the two). But in any combination, too many buyers chasing too few goods = inflation.

But there is a third factor, based upon monetary considerations: Any decrease in the value of dollars. In the current circumstances, I believe that is what has driven the price of CRB over the past decade. From 2002 to 2007, the US Dollar fell 41% — and commodity prices soared.

Yes, prices have risen, but its not the surging demand / constricted supply we associate wit the 1970s type inflation. It can be cured by turning off BB’s printing presses.

>

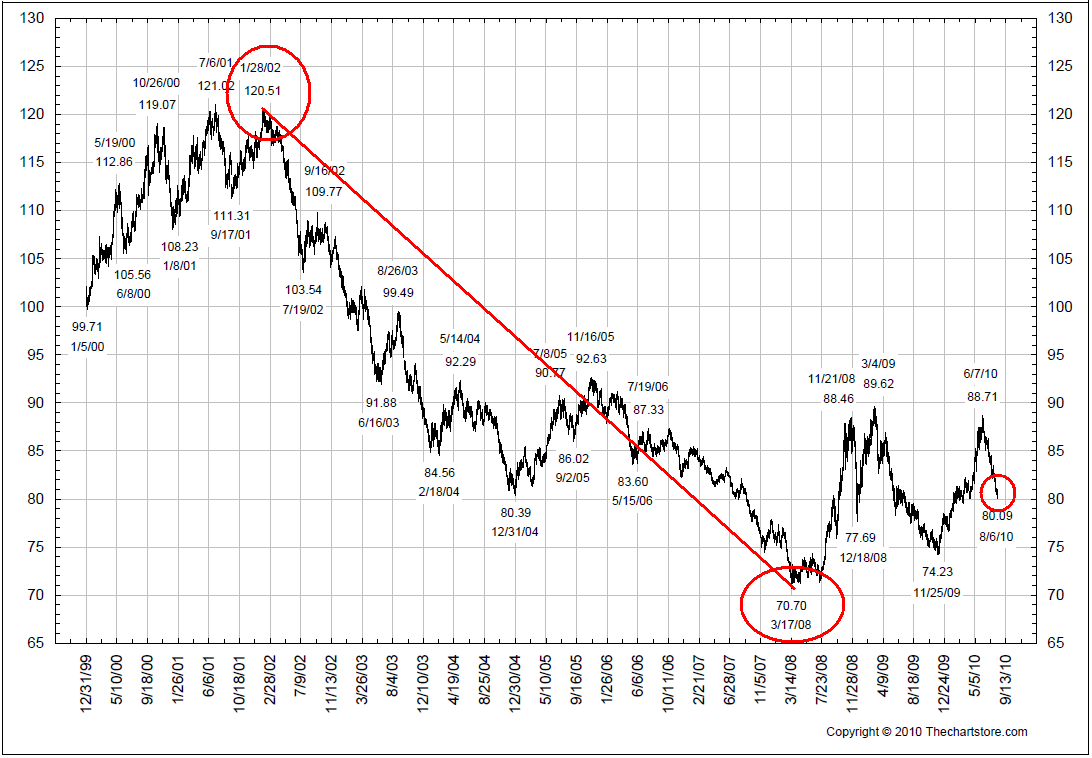

Dollar Index (DY)

>

Hence, the CRB might not be the best evidence of a lack of deflation during a period of slack demand. The cost of commodities priced in hours worked yields a somewhat different conclusion.

~~~

As to the CPI, well, it has built into it an inherent error: Owner’s Equivalency Rent (OER). This understated inflation during period of rising house price — think 2001 -2007. As we noted in this Fed report in 2005, during housing booms:

“Downward pressure on rental prices mainly resulted from an increase in demand for homeownership, which was spurred by historically low mortgage interest rates. As housing starts and home sales surged in the recent recession and recovery, the national rental vacancy rate jumped from 7.8 percent in the fourth quarter of 2000 to 10.2 percent in the fourth quarter of 2003. This effect was compounded by the way owner-occupied housing prices are measured in the CPI. The CPI uses a rental-equivalence approach, measuring the value of the shelter services an owner receives from his or her home. Price movements in owners’ equivalent rent reflect changes in prices of rental units that are comparable in characteristics to owner-occupied homes. Therefore, increased demand for homeownership put downward pressure not only on tenants’ rent but also on owners’ equivalent rent — the largest component in the CPI.”

During the boom, renters became buyers. In the current environment, you must apply the opposite logic: People are reluctant to purchase a falling asset. Hence, traditional buyers become renters. This drives prices higher, and OER — anywhere from 23% to 30% of CPI — goes higher. This is true even as home prices tumbled in fact, its true because homes pries tumbled. Indeed, falling home prices appear cheap, when measured by Rentals — but that metric fails to consider the causal relationship between the two.

The bottom line to me is that neither the CPI nor the CRB Index gives an accurate read of what is gong on with price increases.

Deflation, not inflation, is present, but apparently not accounted for.

>

UPDATE: August 10, 2010 1:45pm

Peter Boockvar writes in:

“Another point I was trying to get across was that deflation is not always a bad thing as we are led to believe by central bankers. In an economic situation where demand is lacking, lowers GDP growth and thus creates disinflation/deflationary pressure, solving that problem by RAISING the cost of goods and services thru money printing is counterintuitive to the basic laws of supply and demand. The law says that if demand is weak, the cost of things must go DOWN to meet that level and thus create an equilibrium. For those however who are very overleveraged, whether business or individual, deflation is not good as debts are paid with shrinking income/revenue. In conclusion, the debate over inflation/deflation is not as simple as ‘it’s one or the other’ and the policy response to both sometimes misses the proper cure for the actual ailment.”

>

Previously:

How Housing Lowers CPI (May 21st, 2005)

Rent vs CPI (June 26, 2005)

From Bubble to Depression via Bad CPI Data (April 7, 2009)

Are Home Prices Too High — or Too Low? (June 28th, 2010)

What's been said:

Discussions found on the web: