• Deflation

• Quantitative Easing (QE2 & QE3)

• A nod to Christopher Hitchens

• The G7 financial system must deleverage to regain a semblance of stability and sustainability. It does not need more credit. It does not need more taxes. It needs more money.

Nothing changed fundamentally to the US or global economies in July to warrant such a sudden and sharp divergence between equities and precious metals (almost 13%). Investor perception, however, did seem to congeal around a unifying theme – “deflation”. Fed Chairman Bernanke and even his hawkish colleague, James Bullard, set the table in July for QE2, as we suspected the Fed would eventually have to do. We should not be surprised with an announcement sometime soon that the Fed will buy more securities related to residential real estate and maybe even commercial real estate. Such quantitative easing equals inflation and we think it should benefit us greatly.

In the US we expect the Fed to buy more MBS and, perhaps, CMBS receivables from creditors, ostensibly freeing their balance sheets to eventually extend more credit. The Fed would pay creditors for the mortgages with newly-digitized money. We expect the markets will begin discounting this likelihood in advance of the November elections. We remain dubious as to how much new money would actually become economically stimulative in the near term. There remains a substantial real estate debt overhang on bank and GSE books, (they remain mismarked awaiting further bailouts), and grass roots borrowers would still lack incentives to sink deeper into debt.

As it stands and citing all appropriate disclaimers, we now expect a total of three rounds of quantitative easing. In the US as elsewhere, QE is a political construct; its timing depends upon domestic social pressures arising from unemployment and economic stagnation, as well as from the ability of foreign policy makers to placate foreign dollar reserve holders (by delivering an adequate supply of precious metals and resources to them?).

The bigger inflation event (QE3?) would use newly created base money for the immediate benefit of debtors. Sending checks to indebted homeowners made out to their creditors would be an example of quantitative easing that would be popular among the masses and economically stimulative. It would allow a new credit bubble to expand and prices of goods, services and assets to increase. We think this form of QE — broad debt socialization – is inevitable. It would require coordination among central banks and fiscal policy makers, which would demand a general acknowledgement that nothing else would work. (This would not be a de-leveraging event, but a transfer of debt from private to public balance sheets.) Frankly, we do not see this materializing yet.

Meanwhile, we think the upcoming increase in the US dollar monetary base will be far less effective than the initial round. QE2 should promote increasing global wealth transference from cash and financial assets in paper currencies to precious metals and finite natural resources.

We would expect the general level of stock markets to oscillate around current levels for an extended period, until the third round of QE is imminent. We would expect the same for bond prices and yields. Once the markets begin to discount QE3, we would expect stock prices to rise. The fate of sovereign and tertiary bonds prices is not as predictable going into QE3. Yields would naturally rise if it is perceived that price inflation would eat into the purchasing power of future principal and interest payments. However, sovereign yields might actually fall and stay low were there to be a formal currency devaluation (see the last section, below).

All the while we expect precious metals, agricultural, basic materials and energy prices to climb consistently through QE2 and QE3. We believe the bull market in precious metals will run faster and higher than consumable commodities and begin to fade only after a third-wave parabolic price shift higher. We think the bull market in consumable commodities will kick-in significantly once consumer confidence and significant (price-generated) nominal output growth returns.

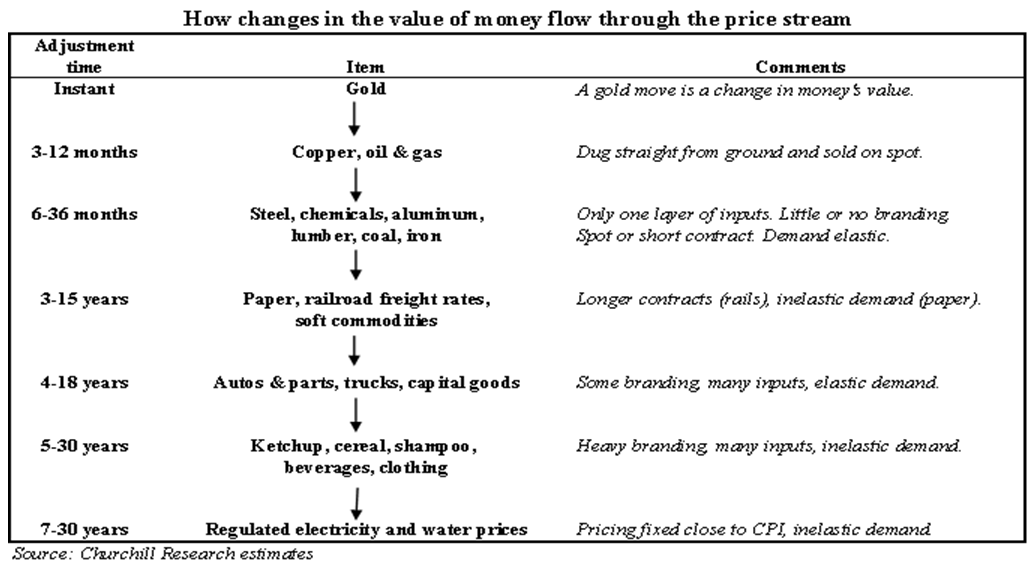

We re-print the diagram above with the permission of Churchill Research. It estimates the link from the change in the value of money through the price stream for goods and services. The logic resonates with us, and is consistent with our thinking since 2007. It succinctly explains our asset allocation rationale amid an investment environment best characterized by credit deflation being offset with monetary inflation.

We plan to ride current trends until financial assets present greater risk-adjusted value. This would require positive real interest rates (at whatever nominal levels) and far greater risk-adjusted values in equities vis-à-vis precious metals and finite natural resources. Perhaps in a few years we will own more cyclical stocks and long-term bonds, which would then more resemble a fund most would call “conventional” by today’s standards. (Perhaps when we begin to do that it won’t be considered conventional?)

***

In his memoir, “Hitch 22”, Christopher Hitchens described a painful life lesson learned at authoritarian English boarding schools:

“The conventional word that is employed to describe tyranny is “systematic”. The true essence of a dictatorship is in fact not its regularity but its unpredictability and caprice; those who live under it must never be able to relax, must never be quite sure if they have followed the rules correctly or not. The ability to run such a “system” is among the greatest pleasures of arbitrary authority…”

Hitchens would no doubt recognize the vagaries of the subjective central bank decision-making apparatus as a capricious pursuit posing as systematic. This is a claim we have made for many years. Can there be any doubt in today’s environment that, for better or worse, the cost of economy-wide credit and the value of a nation’s savings boil down to the subjective decisions of unitary decision makers at the helms of our central banks? (At least, we should hope such decisions have been derived from intelligent people acting independently, not from the banking systems for which they are principally responsible.)

Amid this uncomfortably arbitrary backdrop, there is little value today in extrapolating cause and effect based on theoretical economic orthodoxy. Most of the past generation witnessed an unprecedented credit build-up from low systemic leverage levels coincident with a finite and controllable global economy (US, Japan and Western Europe) and increasing populations within them. That game is over. The G7 has become mature, effectively insolvent and unproductive vis-à-vis emerging economies. It cannot compete globally without sinking deeper into debt.

Combining a subjective monetary policy-making “system” with its inability to scientifically or rigidly make economic prognoses and prescribe solutions should be troubling to all investors (and to everyone else).

We presume you recognize this too as you ask yourself whether or not there will be a “double-dip recession” or whether to side with “austerity” or “stimulus” as a prescription that best fits your personal politics. Exactly who or what do you think will make the ultimate determination? The only lever we can rely on to gain purchase in the current investment environment is this: the path of global markets will be determined by policy makers and politicians, not by natural economic incentives or even by policy makers re-setting our “animal spirits”.

Governments or banking systems, (we’re not sure which and we’re not sure either of them is sure which – so let’s say “both”), are firmly in control of individual wealth, where it will be produced, how it will be distributed and how much will be transferred in aggregate.

And Hitch, our thoughts are now with you during your trying time. We and others that admire your extraordinary mind and indefatigable will, from all corners of the political, social, economic and spiritual spectrum, are better people for having been touched by your pen. Immortality is thus yours, but hopefully not yet.

***

We were asked last month by an iconic international economic figure connected to high-level policy debates to put forth our idea to reset the global economy (flattering indeed). We submitted the following, for which we were ultimately and apologetically told it was “incomprehensible” and therefore would not be passed on:

The yawning gap in the US separating outstanding global debts and base money, (almost 30:1 – $70 trillion/$2.5 trillion), cannot be closed by issuing new debt to debtors. It must be treated with the hair of the dog – a massive coordinated monetary devaluation. A major expansion of the global stock of base money should be administered and then be capped in a credible fashion. It would work in two steps:

1) A coordinated global currency devaluation. The Fed, for example, tenders for private gold holdings at $5000/oz and maintains that bid/offer. As the Fed purchases gold, the gold flows to the asset side of its balance sheet. The Fed funds these gold purchases with newly-digitized money, which flows to banks in the form of net new deposits. This would be a discrete monetary inflation event (devaluation) and a simultaneous deleveraging.

Once the Fed acquires enough gold from the markets, a gold price peg for the US dollar is established. Would this be a gold standard? Yes, if that nominal exchange value is maintained in the open market by the Fed. No, if the Fed decides to periodically adjust that $5000/oz. level following the original exchange. (In fact, tinkering with the official gold price would be a pure example of a monetary agent conducting monetary policy.)

2) A major policy-mandated contraction in unreserved bank lending. Bank reserve requirements should be increased substantially.

These steps would mark a new and sustainable global monetary system. (The reason gold standards “failed” in the past is that they allowed for continued net systemic leverage; not because the basic mechanics of a gold standard are “too restrictive”.)

The economic benefits would be immediate and profound. Financial assets would appreciate in nominal terms making balance sheets solvent. The loan books of global banking systems would be secured again.

Debtors would welcome this devaluation and debt covenants would remain intact. Nominal wages and asset prices would rise while debt balances would remain constant. The burden of repaying debt would be greatly diminished, not the principal amount of the debt itself.

Bondholders, dollar reserve holders and retirees would suffer losses in purchasing power; however, inflating away the burden of debt would likely act as a massive economic stimulant, which would, in turn, give policy makers room for fiscal maneuvering.

Global wage rates in established and emerging economies would track towards equilibrium. Affordability would rise. Prices for goods and services could fall without having a deleterious impact on employment. Workers would naturally migrate where opportunity lay and would again be able to save their wages for future consumption.

Is there a good reason this plan is not being discussed by serious-minded policy makers?

Would our suggestion above really be “incomprehensible” to a room full of economists and economic policy makers or would it be politically uncomfortable? It is time to move on. The global economy needs an institution to conduct global monetary policy rather than a federation of politicized central banks managing domestic credit policies to suit banking systems and deficit spenders. The G7 financial system must deleverage to regain a semblance of stability and sustainability. It does not need more credit. It does not need more taxes. It needs more money. ¿Comprendé?

Paul Brodsky

pbrodsky@qbamco.com

Lee Quaintance

lquaint@qbamco.com

What's been said:

Discussions found on the web: