(This is a series giving a basic explanation of the current foreclosure fraud crisis from Mike Konczal; This is Part Two; you should also see Part One )

The SEIU has a campaign: Where’s the Note? Demand to see your mortgage note. It’s worth checking out. But first, what is this note? And why would its existence be important to struggling homeowners, homeowners in foreclosure, and investors in mortgage backed securities?

There’s going to be a campaign to convince you that having the note correctly filed and produced isn’t that important (see, to start, this WSJ editorial from the weekend). This is like some sort of useless cover sheet for a TPS form that someone forgot to fill out. That is profoundly incorrect.

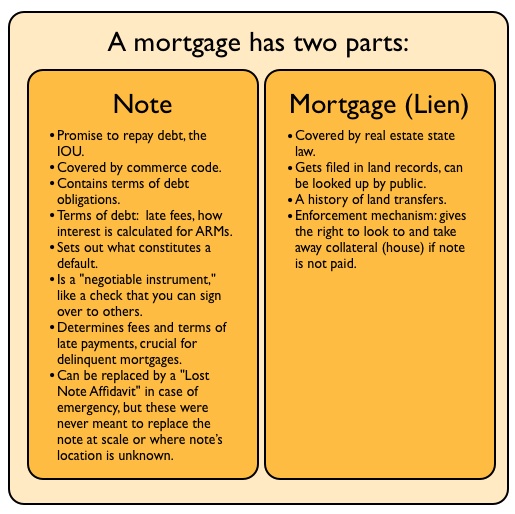

Independent of the fraud that was committed on our courts, the current crisis is important because the note is a crucial document for every party to a mortgage. But first, let’s define what a mortgage is. A mortgage consists of two documents, a note and a lien:

The note is the IOU, it’s the borrower’s promise to pay. The mortgage, or the lien, is just the enforcement right to take the property if the note goes unpaid. The note is crucial.

Why does this matter? Three reasons, reasons that even the Wall Street Journal op-ed page needs to take into account. The first is that the note is the evidence of the debt. If it isn’t properly in the trust then there isn’t clear evidence of the debt existing.

And it can’t be a matter of “let’s go find it now!” REMIC law, which governs the securitization, is really specific here. The securitization can’t get new assets after 90 days without a tax penalty, and it can’t get defaulted assets at all without a major tax penalty. Most of these notes are way past 90 days and will be in a defaulted state.

This is because these parts of the mortgage-backed security were supposed to be passive entities. They are supposed to take in money through mortgage payments on one end and pay it out to bondholders on the other end, hence their exemption from lots of taxes; the tradeoff is that they can’t be de facto managers of assets, and that’s what going to find the notes would require.

For Distressed Homeowners

The second is that it also matters a great deal for homeowners who are distressed. The note lays out the terms of late fees and other penalties. As we will discuss in the next section about mortgage servicers, the process of trying to get people behind on their payments current instead of driving them into bankruptcy has broken down. But for now it’s clear that mortgage servicers don’t have great incentives to get distressed homeowner’s records correct.

There’s well-documented evidence that extra fees are tacked on to mortgages that have fallen behind, fees that aren’t following the terms of the note. This is usually only found out in bankruptcy where there is a lawyer (and multiple parties), not in foreclosure cases. But if homeowners wants to challenge whether what the servicers claim is the correct final due amount, the terms of the note are necessary for the court.

This will matter a great deal for many homeowners. Small, marginal differences in the total owed could allow for a short sale. It could determine if the homeowner has any equity in their home. And this can only be determined by producing the note.

For Investors, Who Took This Seriously at the Beginning

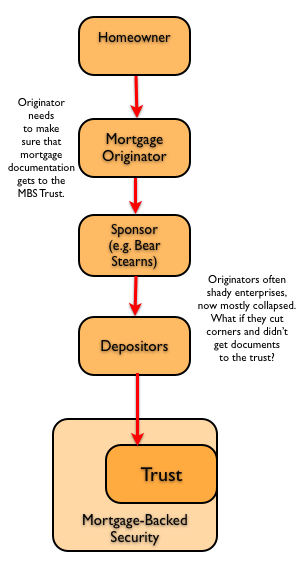

Last reason: you can tell it’s important because all the smartest finance guys in the room thought it was important. Let’s look at a Pooling and Service Agreement form from 2006 between “GS MORTGAGE SECURITIES CORP., Depositor, and DEUTSCHE BANK NATIONAL TRUST COMPANY, Trustee.” (h/t Adam Levitin for this example.) Let’s reproduce the chart from part 1 to see the chain between depositors and trustees who oversee the trust:

So what agreement did they come to when it comes to the proper handling of notes in securitization? Did they think this was no big deal, or that it is something serious? From the PSA (my bold):

(b) In connection with the transfer and assignment of each Mortgage Loan, the Depositor has delivered or caused to be delivered to the Trustee for the benefit of the Certificateholders the following documents or instruments with respect to each Mortgage Loan so assigned:

(i) the original Mortgage Note (except for up to 0.01% of the Mortgage Notes for which there is a lost note affidavit and the copy of the Mortgage Note) bearing all intervening endorsements showing a complete chain of endorsement from the originator to the last endorsee, endorsed “Pay to the order of _____________, without recourse” and signed in the name of the last endorsee…

The Depositor shall use reasonable efforts to cause the Sponsor and the Responsible Party to deliver to the Trustee the applicable recorded document promptly upon receipt from the respective recording office but in no event later than 180 days from the Closing Date….

In the event, with respect to any Mortgage Loan, that such original or copy of any document submitted for recordation to the appropriate public recording office is not so delivered to the Trustee within 180 days of the applicable Original Purchase Date as specified in the Purchase Agreement, the Trustee shall notify the Depositor and the Depositor shall take or cause to be taken such remedial actions under the Purchase Agreement as may be permitted to be taken thereunder, including without limitation, if applicable, the repurchase by the Responsible Party of such Mortgage Loan.

Read that again through to the end and use the chart to follow the chain. If more than 0.01% (!) of mortgage notes weren’t properly transferred, the trust can force the sponsor (in this case, Goldman Sachs) to repurchase the bad mortgages. And this is just one contract for one part of the ~$2.6 trillion dollar mortgage backed securities market. How’s that for systemic risk? Especially if this is found to be widespread….

Looking at the documents you see that the smart guys who created these mortgage-backed securities put large poison pills into them to try and prevent the kind of note fraud we are currently experiencing as a country. They took the policing and legal recourse (and legal ability to cover their ass) very seriously on this issue. So seriously they can force repurchases of this bad debt.

So don’t believe the hype of anyone who says these are just technicalities; the people who wrote the contract didn’t believe they were.

(Special thanks to Katie Porter and Adam Levitin, who you can read at credit slips, as well as Tom Adams and Yves Smith, who you can read at naked capitalism, for in-depth discussions on this material.)

~~~~

This is the second of a 5 part series from Mike Konczal, a former financial engineer, is a fellow with the Roosevelt Institute, who also blogs at New Deal 2.0, and is working on financial reform, the 21st century economy, structural unemployment, inequality, risk sharing, consumer access to financial services and more generally what it means to have a social contract in a financialized, post-industrial economy.

What's been said:

Discussions found on the web: