By now you’ve heard about the $63 million Warhol, the $69 million Modigliani and the $43 million Roy Lichtenstein paintings that sold in the past two weeks. You probably didn’t know that a Chinese vase sold for £53 million (that’s more than $75 million) yesterday in a provincial English town.

By now you’ve heard about the $63 million Warhol, the $69 million Modigliani and the $43 million Roy Lichtenstein paintings that sold in the past two weeks. You probably didn’t know that a Chinese vase sold for £53 million (that’s more than $75 million) yesterday in a provincial English town.

Either way, it wasn’t hard for you to conclude that the art market is back in a big way. The two-week agenda-setting New York sales that just concluded did $1.25 billion in turnover. That’s not as much as the height of the art bubble in 2007-2008 but back around the run-up levels of 2006. (For more charts see artmarketmonitor.com)

We’re all adults here, so I don’t have to explain to you that there’s nothing immoral or offensive about works of art trading on a regular basis for eight and nine figure sums. But since that is a common reaction to big numbers in the art world, let’s remind ourselves — and everyone else — that no wealth is created or destroyed by the art market.

The art market is a simple distribution and exchange machine. When a Chinese billionaire pays someone $75 million for a dusty old piece of bric-a-brac, as just happened in the UK, the recipients are free to use that money to build a school or hospital, support their favorite charity or simply pay some taxes.

The big knock on the art market is the obscenity of the sums but in these fiscally strapped times we should be rooting for more of these transactions because each triggers a capital gains tax payment. With the three important estates being sold at Christie’s this week, there would also be a fair amount of death duty coming to the government if Congress could ever sort out the appalling situation surrounding estate taxes.

The big knock on the art market is the obscenity of the sums but in these fiscally strapped times we should be rooting for more of these transactions because each triggers a capital gains tax payment. With the three important estates being sold at Christie’s this week, there would also be a fair amount of death duty coming to the government if Congress could ever sort out the appalling situation surrounding estate taxes.

So the question about the art market isn’t whether it is a sign of decadence but a financial one. Why are buyers so eager to trade cash for objects? There the answer is relatively easy to see.

The low interest rates being used to heal the world economy after the debt crisis have created a thriving art market as a by-product. Blue-chip art is no different from gold. It’s equally useless and almost as universally valued. So with gold making new highs at $1400, it should surprise no one that art prices for recognized and fairly fungible artists like Andy Warhol are back at the levels (or beyond) of the art boom of 2007-2008.

Art is like real estate, highly sensitive to interest rates. Unlike real estate, there’s very little leverage in the system. You buy art with cash. What leverage there was in the system got squeezed out over the last two years of pain.

It used to be that your money was trapped in the art because transactions were few and most owners hoped to donate their art to a museum where they’d realize the value in a tax break and ego boost. But the first decade of the new century has seen the emergence of a deeper, broader, faster and more frenetic art market where buyers can find sellers faster and better than ever before.

Plunking $20 million into a Matisse is no longer a means to decorate your fabulous house, acquire a trophy of your success or show off your worldly sophistication and taste, though it still accomplishes all of those. Buying that Matisse is now a half-decent store of value.

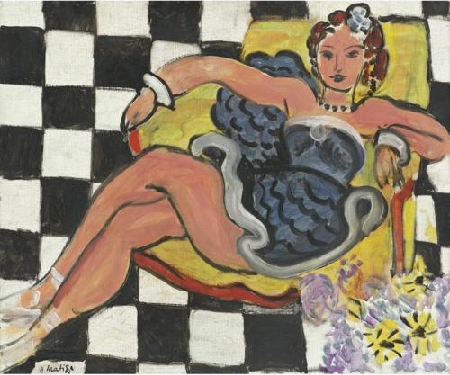

Let’s take an interesting example from last week. This painting (left) by Matisse was purchased in London at the height of the height of the credit bubble in June of 2007. The buyer paid £11 million or $22 million at the exchange rate of the time.

Let’s take an interesting example from last week. This painting (left) by Matisse was purchased in London at the height of the height of the credit bubble in June of 2007. The buyer paid £11 million or $22 million at the exchange rate of the time.

In the old days of the art market, you would be stuck with a work like that for a generation. Sales are said to be driven by work that’s “fresh to the market,” which is auction-house speak for a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity (so make sure you’re money-market account is topped off.)

These days, a good painting is a good painting no matter when it is sold. With many new buyers coming into the market, especially new money from China that’s hoovering up everything in sight even without the Yuan having had to appreciate, there’s always someone to sell your quality work on to.

That’s what happened with the Matisse. Whoever bought it 2007 needed to get their money out in 2010. We know this because they took a risk in putting the work back on the market. Sotheby’s estimated it far below the original selling price the auction house achieved in London. The market maker was signaling the sellers expectations: make me an offer!

The painting could have easily sold for $12 million which would have been quite a loss for the buyer who paid more than $20m three and a half years ago. That’s how we know he was in a desperate bind or at least valued cash over the painting at whatever level he could acquire it.

Risk, however, can get rewarded. When the hammer sounded at the end of the bidding at Sotheby’s, the seller was getting $18.5 million. Then came the currency play. Because the pound has dropped so far since 2007, that $18.5 million works out to slightly more than £11 million. Not only did the owner who briefly held the Matisse get out alive, he or she made a small profit.

Shortly after the buyer acquired the Matisse in 2007, the S&P hit a double top of 1550 in July and October. Had the same $20 million gone into an index fund, it would be worth $15.4 million today even with the same reflation-backed Fed boost.

This is an isolated example. But it does illustrate the temptation to use art to store value in a chaotic economy. The majority of buyers these last two weeks are not thinking of the art as a safety deposit box. But it can’t ever be totally out of mind.

If things go South again, especially here in the US, art offers one final advantage. It’s portable wealth that’s not subject to currency controls. If you’re very rich, you can ship your art to Switzerland, London or Singapore to be stored in a state-of-the-art facility and not have to worry about the Feds tracking it as funds.

Believe it or not, that’s where the majority of art ends up these days, sitting in storage waiting for the right time and place to be shown or sold.

What's been said:

Discussions found on the web: