Chrystia Freeland, the FT’s former US Managing Editor and current trophy editor at Reuters, has a cover story in The Atlantic that just came out this week on the formation of a new global class of super-rich who have more in common with each other than they do with their neighbors and countrymen.

The rise of this new class is permanent and has important consequences that we’ve barely begun to see. Its emergence has been a long-standing trend that Freeland does a very good job of describing through a variety of dimensions. The story reads like a chapter-by-chapter synopsis of a book (or book proposal) often veering into the kind of “I can tell you because I was there” style of access reporting. But that doesn’t take away from the value of identifying and animating this new class:

Its members are hardworking, highly educated, jet-setting meritocrats who feel they are the deserving winners of a tough, worldwide economic competition—and many of them, as a result, have an ambivalent attitude toward those of us who didn’t succeed so spectacularly. […]

As Glenn Hutchins, co-founder of the private-equity firm Silver Lake, puts it, “A person in Africa who runs a big African bank and went to Harvard might have more in common with me than he does with his neighbors, and I could well share more overlapping concerns and experiences with him than with my neighbors.” The circles we move in, Hutchins explains, are defined by “interests” and “activities” rather than “geography”: “Beijing has a lot in common with New York, London, or Mumbai. You see the same people, you eat in the same restaurants, you stay in the same hotels. But most important, we are engaged as global citizens in crosscutting commercial, political, and social matters of common concern. We are much less place-based than we used to be.”

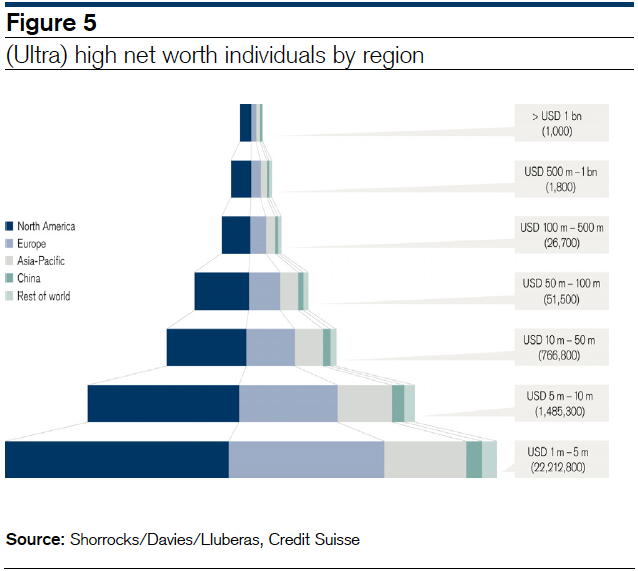

Freeland doesn’t provide much data on these people. It’s not that kind of a story. But there are easily available numbers that are worth looking at. According to Credit Suisse, there are more than 80,000 individuals around the world with assets of $50 million or more. Lower the bar to $30 million, as Cap Gemini does in their World Wealth Report, and you get a number above 93,000.

That’s a stadium full of very rich people and we’re not even including their families who provide many of the social and cultural connections that classes are created from. That’s 93,000 parents with kids in college or getting married or looking for internships. That’s 93,000 vacations, charities and who knows how many second homes.

Obviously not all of those 93,000 persons are part of this new global class. But enough of them are and they spawn another group of those who many not be as rich but are involved in professions and pursuits that put them in constant contact with this elite.

Taken together, they’re a substantial population. Freeland tries to get inside their heads and explain some of their biases. Seen from their perspective, the path beyond the financial crisis looks very different from what hear on the news every day. National concerns no longer matter.

It’s not simply callousness but a broader perspective. Here’s Freeland again:

The U.S.-based CEO of one of the world’s largest hedge funds told me that his firm’s investment committee often discusses the question of who wins and who loses in today’s economy. In a recent internal debate, he said, one of his senior colleagues had argued that the hollowing-out of the American middle class didn’t really matter. “His point was that if the transformation of the world economy lifts four people in China and India out of poverty and into the middle class, and meanwhile means one American drops out of the middle class, that’s not such a bad trade,” the CEO recalled.

Source:

The Rise of the New Global Elite

by CHRYSTIA FREELAND

January 10, 2011; The Atlantic

http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/print/2011/01/the-rise-of-the-new-global-elite/8343/

What's been said:

Discussions found on the web: