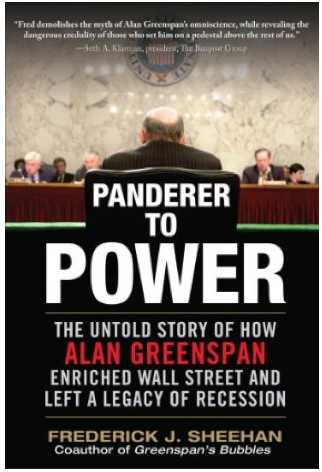

Frederick Sheehan is the co-author of Greenspan’s Bubbles: The Age of Ignorance at the Federal Reserve.

Frederick Sheehan is the co-author of Greenspan’s Bubbles: The Age of Ignorance at the Federal Reserve.

His new book, Panderer for Power: The True Story of How Alan Greenspan Enriched Wall Street and Left a Legacy of Recession, was published by McGraw-Hill in November 2009. He was Director of Asset Allocation Services at John Hancock Financial Services in Boston. In this capacity, he set investment policy and asset allocation for institutional pension plans.

~~~

Following are some of my remarks prepared for Allen & Company’s Fifteenth Annual Arizona Conference. The discussion, “Munis and the Euro: Crises or Opportunities?”, took place on March 8, 2011. The moderator was Senator Bill Bradley, Allen & Co., New York. Participants were Dick Ravitch, Ravitch, Rice & Company, New York; David Kotok, Cumberland Advisors, Sarasota, Florida; Uri Dadash, The Carnegie Endowment, Washington, DC.; and Frederick J. Sheehan.

The panel discussion was conversational, so less formal and more wide-ranging than what follows. I have written about much of the “Ignorance” in previous dispatches, so omit redundent notes here. The “Opportunity” will also be familiar to many readers, and so is repeated in truncated form at the end.

To the prepared remarks:

I will discuss four topics:

First, some background to current problems;

Second, why it is not wise to make predictions about the amount and size of defaults;

Third, some areas where municipal solvency and bonds are most vulnerable;

Fourth, the opportunities.

FIRST, THE BACKGROUND TO CURRENT PROBLEMS

I will start with some numbers:

In 1995, $153 billion of mortgage debt was borrowed by home buyers. In 2005, it increased $1.1 trillion.

As for municipal borrowing:

In 1996, states and municipalities retired a net $7 billion in debt. In 2007, they borrowed $215 billion.

At the same time, tax receipts were rising fast.

In 2003, State and Local Government Current Receipts were $979 billion. By 2007, receipts were $1,304 billion.

This all leads to the conclusion that municipal spending no longer concerned itself with the future – the spenders simply extrapolated their budgets and borrowing into a splendid future.

The link between real estate bubbles and municipal finance bubbles is as old as the hills.

I will continue with a quote:

A.M. Hillhouse, author of a splendid study of municipal bonds – Municipal Bonds: A Century of Experience, 1836 – 1936, analyzed the U.S. municipal bond market across that century. He concluded:

“[T]he major portion of overbonding by municipalities arises out of real estate booms.”

Hillhouse, who considered his book a font of wisdom for future generations, wrote:

“There will be no justification for a city’s coming forward [in the future] with the excuse that… its revenue has dried up in times of falling property values… [T]he cause of the debt trouble [must be regarded] as an unwarranted failure of the city to adjust its borrowing program to certain known facts.”

His book, as you might expect, never went to a second printing. Nevertheless, there should have been no doubt that a municipal bust would follow the residential mortgage crash. I wrote a study, “The Coming Collapse of the Municipal Bond Market” in 2009. The title may or may not turn out to be accurate, depending on one’s portfolio, but there was and is no doubt municipal extravagance had left us with a grave problem.

Current theories and books written about the Depression do not dwell on the 1920s real estate boom. Real estate lending in the 1920s might rival the recent debacle, in form, if not degree. There was a flight to the suburbs. Inflated civic conceit hired construction crews to build houses, roads, sewers, schools, skyscrapers, and highways that crossed the country for the first time. When Treasury “Secretary Mellon endeavored to cut back federal spending, state and local governments stepped up spending at a rate that more than offset the Mellon program….”

I will continue with some more quotes – my point being that it is not necessary to talk about the past two decades to understand why municipal finance is in disarray. The town librarian could have gathered previously documented warnings. In those locales where the library has been closed for lack of funds – and there are many – a moderate level of common sense would have noted the city elders had lost control, and possibly, their minds.

In March, 1933, Professor Herbert D. Simpson gave a lecture at the 45th annual meeting of the American Economic Association:

“Throughout this period – [he was speaking of the 1920s] – there was another form of real estate speculation, not commonly classified as such, but one that has had disastrous consequences. This is the real estate “speculation” carried on by municipal governments, in the sense of basing approximately 80 per cent of their revenues upon real estate and then proceeding to erect a structure of public expenditure and public debt whose security depended largely on a continuance on the rate of profits and appreciation that had characterized the period from 1922-29.”

Per Hillhouse, Simpson tried to steer municipal financing from its dependence on house building and price appreciation:

“The financial difficulties of local governments in consequence of both the inflation and deflation of real estate values demonstrates strikingly the unwisdom of a revenue system concentrated so heavily upon real estate…”

This elicits a truism that was ignored in equal parts during our twenty-first century mortgage and municipal bubbles: When asset prices fall, the collateral falls, but borrowed money, linked to the original asset price, still needs to be paid back.

Simpson recounted the credulity with which the citizenry accepted heavier property taxes in the 1920s. Similar to our recent splurge, the Jazz-Age home dweller did not mind that property tax revenues, municipal borrowing and municipal spending were all inflating – at unsustainable rates. The forgotten professor went on:

“During this period of prosperity, real estate taxes were paid with little complaint…. [U]nder these conditions, public expenditures expanded and taxes were increased without protest; and public officials exploited the real estate groups as systematically and thoroughly as the real estate groups had exploited the rest of the public. The result has been a structure of public expenditure which has been difficult to curtail, and a volume of indebtedness whose solvency is now jeopardized on a large scale.”

Morgan partner Dwight Morrow was not a fan of his New Era – the 1920s New Era. He knew the asset inflation would come to a bad end. Morrow wrote: “It is the social effect which is so dangerous. It transfers the habit of spending from those who have long experience of spending to those who have no experience.”

Today, our state-of-the-art Federal Reserve is actively and explicitly promoting and feeding asset inflation.

SECOND, WHY IT’S NOT WISE TO MAKE PREDICTIONS ABOUT THE AMOUNT AND SIZE OF DEFAULTS: THERE ARE TOO MANY “DON’T KNOWS”

1 – We Don’t Know if unions and municipalities will reach agreements over benefit reductions

2 – If they do not reach an agreement, and the decision goes to a court, We Don’t Know how courts will rule. Union pension plans are legal contracts. Yet, pensions and benefits are unsustainable. How will judges rule?

It is worth keeping in mind that most, if not all, states have legal recourse to amend pensions under certain conditions. In California – I quote: “an employee does not have the right to any fixed or definite retirement benefits but only to a substantial or reasonable pension.”

I am quoting Amy B. Monahan, law professor at the University of Minnesota, from a paper in which she addresses legal remedies available to states and used in the past to reduce pension benefits of public union workers.

[Amy B. Monahan, Visiting Associate Professor, University of Minnesota Law School and Associate Professor, University of Missouri School of Law. “Legal Limitations on Public Pension Reform,” Presented at Vanderbilt University, conference on “Rethinking Teacher Benefit Retirement Systems,” February 19-20, 2009]

By the way, recently there have been federal legislation initiatives floating around that would allow states to declare bankruptcy. There is at least an implicit intention, by some parties, to use this legislation to reduce public sector wages. This is unnecessary. If an agreement cannot be reached among the parties, the state courts have the authority to reduce benefits.

3 – We Don’t Know what the federal government – including the Federal Reserve – will do if states and cities go into default. Treasury Secretary Geithner may copy Hank Paulson’s bazooka maneuver with Congress. The Fed may, or may not, buy a trillion dollars worth of municipal bonds before the Senate Banking Committee puts Chairman Bernanke in the witness box.

3 – We Don’t Know what cities and towns that rely on a certain level of state aid to pay the bills will do. This, of course, is a Don’t Know only after We Do Know that a state has stopped or reduced local aid payments.

4 – We Don’t Know if states and municipalities will tell the feds to fund their own mandates. That is, regarding state and local costs that were either signed into law or regulations imposed at the federal level, but were not funded by the federal government. We are seeing some opening salvos, here, in Arizona, which is making cuts to Medicaid. I think cities and towns will test the waters, for example, in schools – where, instead of laying off teachers, they may drop federally mandated requirements.

5 – We Don’t Know, once this step is taken, the response of the federal government and the courts.

6 – We Don’t Know if states and municipalities will raise taxes if they are unable to meet municipal bond payments.

Rating-agency and brokerage-firm literature publish statements such as the following:

“What makes general obligation bonds…unique is that they are backed by the full faith and credit of the issuing municipality. This means that the municipality commits its full resources to paying bondholders, including general taxation and the ability to raise more funds through credit.”

This is only true on occasion. A good place to study the variety of decisions is with a paper written by Kevin A. Kordana, an Associate Professor of Law at the University of Virginia. [“Tax Increases in Municipal Bankruptcies,” Virginia Law Review, September 1997, Volume 83, Number 6.]

7 – Another Don’t Know is the level of ignorance in cities and towns, where it is too often the case that nobody understands the financial situation. An outsider who drops by city hall can be amazed at how little anyone knows.

8 – Finally, and most importantly, the decision – or indecision, as it may be – to break the cities’ or towns’ contractual obligation to pay its lenders includes a lack of will among the parties. Here, we will have to wait and see.

THIRD, SOME AREAS WHERE MUNCIPAL SOLVENCY AND MUNICIPAL BONDS ARE MOST VULNERABILE:

Disagreements about public employee benefits and payments are in the headlines, so I will start there.

I used to work with investment committees of corporate, union, and municipal pension plans, to design pension policies. This included analyzing assets and liabilities. Understanding future, annual cash flows – outflows to retirees – was important for duration- and cash-matching of assets to payments. I said to the pension committee of a town in 1989: “There will come a point when you won’t be able to pay these benefits.”

This was not a surprise at all. They knew that. They had no say in negotiations between the different union groups in the town and the selectmen who approved the benefits. There had been an increase in future benefits through improvements to the benefit formula almost every year for several years. And, there was a boost to the formula almost every year during the next decade.

The proportion of retirees to current workers was small back then. Plus, discounting the much higher future payments 20 or 30 years out produced tiny numbers, that, over time, have blossomed. Now, we have reached the point when the benefit payments are exploding as a percentage of costs for many municipalities.

A second problem is maintenance expenses for municipalities that went on a building spree. A rule of thumb is they are about 30% higher than the prior trend.

A third potential problem is that many cities and towns are dependent on continual access to the bond market. If Treasury rates jump 3% or 4% in a failed auction, the light bill may not be paid.

A fourth means by which municipalities have telescoped the future into the present is by raising money through General Obligation bonds that is supposed to be used for a specific purpose but, the money is instead used to cover current expenses.

A fifth problem is the next step in the misuse of General Obligation proceeds. There are cities and towns that raise enough additional money in the bond market to cover the projected rise in next year’s operating expenses.

MY FOURTH AND FINAL TOPIC IS OPPORTUNITES –

Opportunities in municipal bonds will spring from ignorance. They already have. There may be a panic of indiscriminate selling when owners of munis understand a municipal bond is not simply “money good.” Such ignorance has produced great buying opportunities in the past.

For instance, in May 1933, all City of Miami bonds (with yields ranging from 4-3/4% to 5-1/2%, and maturities from 1935 to 1955) were quoted at $26. In the mid-1970s, the same combination of ignorance and fear created great buying opportunities for New York City bonds. All bonds traded for $25.

It will be awhile before buyers should pile in, but the wait may be worth it. A bond veteran who traded municipals in the 1970s – one who actually understood the securities – told me that buying New York City bonds at the bottom was extremely profitable.