One of the biggest problems caused by the Contemporary Art market boom of the last 13 years is the ways in which it has confused the world about how the art market works and what determines value. The issue isn’t trivial. The art market is generally believed to have $50-60 billion dollars a year in global turnover. Which makes it a substantial industry by any measure.

The problem is that very little information about this non-trivial industry is available. The two main auction houses—Christie’s and Sotheby’s—together represent less than 20% of the overall industry which remains dominated by small private firms that do not disclose information about sales or prices. A few services like Artnet.com provide auction prices for art and the New York Times has seized upon this information to point out that not all artists are rising in value.

The problem is that very little information about this non-trivial industry is available. The two main auction houses—Christie’s and Sotheby’s—together represent less than 20% of the overall industry which remains dominated by small private firms that do not disclose information about sales or prices. A few services like Artnet.com provide auction prices for art and the New York Times has seized upon this information to point out that not all artists are rising in value.

Imagine the Times running a story on the front page of the business section that says “Some Bond Prices Fall as Most Rise.” If you were to read that story, your interest would be in the credit issues specific to the companies with falling bond prices. It would be an indication that the companies themselves faced peculiar problems unrelated to the overall bond market which is rising. So what you would want to see from the story is details on why each company’s bonds were scaring investors.

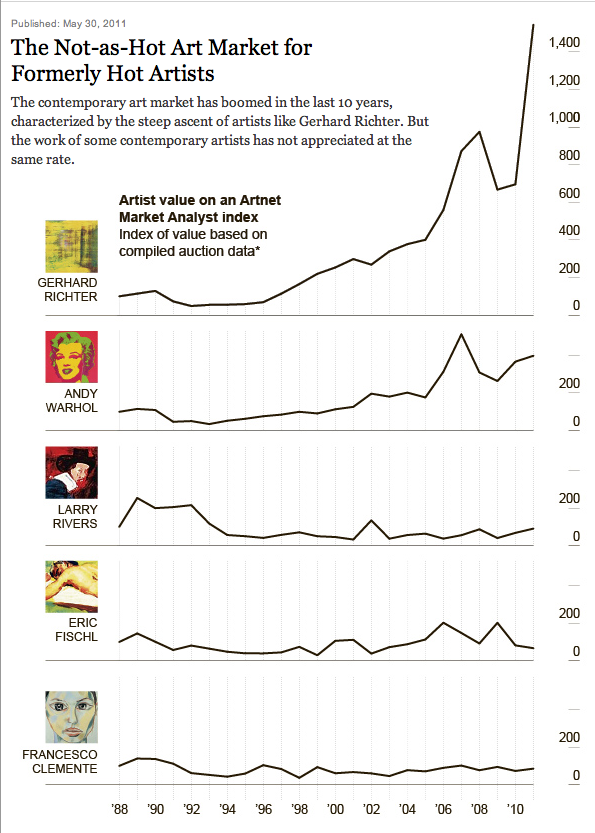

That’s essentially what today’s art market story is about. Each of the three living artists whose Artnet market indices—a product that doesn’t seem to be available through artnet.com—are the featured graphic in the Times story online has his own market story to tell. It’s a little like Tolstoy’s famous line about families: All artists with rising markets are all alike; every artist with an unhappy market is unhappy in its own way.

The Times picks out Larry Rivers, Francesco Clemente and Eric Fischl as examples of unhappy artists. Looking at the chart for Rivers, we see that his price index rose during the last great art recession. While others were licking their wounds on the art market in the early 1990s, Rivers was enjoying a moment in the spotlight. Then, again, in 2002, another short trough in the art market, Rivers rises through it only to fall again before next market acceleration.

According to the Times’s chart, Rivers’s prices are waxing even as the story adduces this bit of market ugliness:

For example, a Dutch Masters painted cigar box, created by Rivers and valued as high as $40,000 last year, sold in September for less than $4,000.

There could be many reasons for the difference in prices reflected here. One is that the two works are from a similar series but wildly dissimilar in size, condition or quality. There’s also the chance that the market for Rivers’s work was effected by the revelations in the Times nearly a year ago (a couple of months before the $4,000 sale) of Rivers’s daughters accusations about a disturbing and distasteful video project undertook with her.

The Times does at least try to explain that Francesco Clemente’s market has changed since leaving Gagosian gallery. It would be difficult to trace the cause and effect of the loss of representation. An artist and a gallery have a complex relationship. The gallery supports and shapes the artist’s market but tensions can come from either end of the value chain. The artist’s new work–its volume or quality–may make the gallery’s role untenable. On the other side, collectors taste, interests or estimation of art history may move away from the artist leaving him frustrated with his gallery’s lack of sales.

Art advisors will tell you that Clemente has some supply issues that gum up his prices. Then, again, looking at the chart, Clemente seems to have had a fairly consistent market since 2004.

Then there is Eric Fischl whose charts show a bubbly path that follows the boom, bust and recovery before falling off a cliff in the last year and a half. Whether Fischl, still a fairly young artist when one looks at an old lion like Lucien Freud who had to wait will into his senior years to command impressive auction prices, will eventually be seen as an important artist remains to be seen. But then, again, the art market is cluttered with painters who were huge during their lifetimes but faded into obscurity as time went on.

Value in the art market is conferred by art history with an emphasis on the history. Artists and artworks become more meaningful and valuable over time because of events beyond the artist’s control. If you anticipate or influence later artistic achievements, your work becomes more valuable to museums and collectors. One of the goals of art collecting is tracing ideas through art history. That’s what many collectors are after when they buy—something significant, something meaningful, something lasting.

Unfortunately, there’s no telling in the short term which artists will remain relevant. Like stocks or options, art prices are really just claims on an artist’s future cultural relevance and importance. So we shouldn’t be surprised when that value fluctuates.

>

Source:

Does Money Grow on Art Market Trees? Not for Everyone

ROBIN POGREBIN and KEVIN FLYNN

New York Times; May 30, 2011

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/31/arts/design/not-all-art-market-prices-are-soaring.html

What's been said:

Discussions found on the web: