Macro Factors and their impact on Monetary Policy,

Macro Factors and their impact on Monetary Policy,

the Economy, and Financial Markets

MacroTides.newsletter@gmail.com

Investment letter July 20, 2011

j

j

j

j

Budgetary Moon Shot

On May 25, 1961 President Kennedy announced the ambitious goal of landing an American astronaut on the moon within a decade. It was an extraordinarily audacious endeavor, but President Kennedy felt it was necessary for the United States to respond to the successes the Soviet Union had already achieved with their space program. In essence, President Kennedy was marshaling our nation’s resources and resolve to address a threat to our long term security. As he addressed a special joint session of Congress more than 50 years ago, he said, “I believe we possess all the resources and talents necessary. But the facts of the matter are we have never specified long range goals on an urgent time schedule, or managed our resources and time so as to insure their fulfillment.”

Earlier this month, NASA launched its final space shuttle mission. Now, American astronauts will have to depend on the Russian space program to visit the International Space Station. It appears our space program has come full circle since President Kennedy’s speech 50 years ago. Given the current state of our economy, the end of our manned space program seems an apt metaphor for our country, if we choose to let it be one.

In 1961, the Soviet Union represented a clear threat to the United States, which made it easier for the American people to support the lofty goals of the space program. Whenever the United States has been threatened by forces outside our country, the American people have come together to defeat our adversaries. Whether it was fighting the Japanese or Nazis in World War II, or the Cold War with the Soviet Union, the enemy was clearly defined and the threat to the United States was basically determined to be real.

Today, we are facing one of the most significant threats in our nation’s history, but most Americans do not appreciate or understand the magnitude of this threat. As a result, there is no sense of urgency or consensus on how we should address the myriad of challenges we face. Whether it is the budget deficit, chronic unemployment, health care costs, Medicare, social security, education, immigration, or partisan politics, the only constancy is the cacophony of talking heads that bombard listeners with party ideology, rather than objective clarity. When discussing the coming budget debate a few months ago, we used a phrase from a Pink Floyd song to describe the quality of the discourse we expected, “It’s a battle of words and most of them are lies”.

It is far easier to rally around the flag, when the threat or enemy is coming from outside our borders, as has previously been the case. So the first step we must take is to understand and accept that we created most of the problems we face ourselves. Therefore, the solutions are not going to negatively impact those outside our country, but will instead affect our family, friends, or neighbors. This reality is going to make it much tougher to establish a clear goal, and maintain the resolve necessary to repair and reinvigorate our economy. This isn’t going to be easy, and it will take most of the next decade to accomplish, since the problems we’re facing took decades to develop. There are no easy or quick fixes.

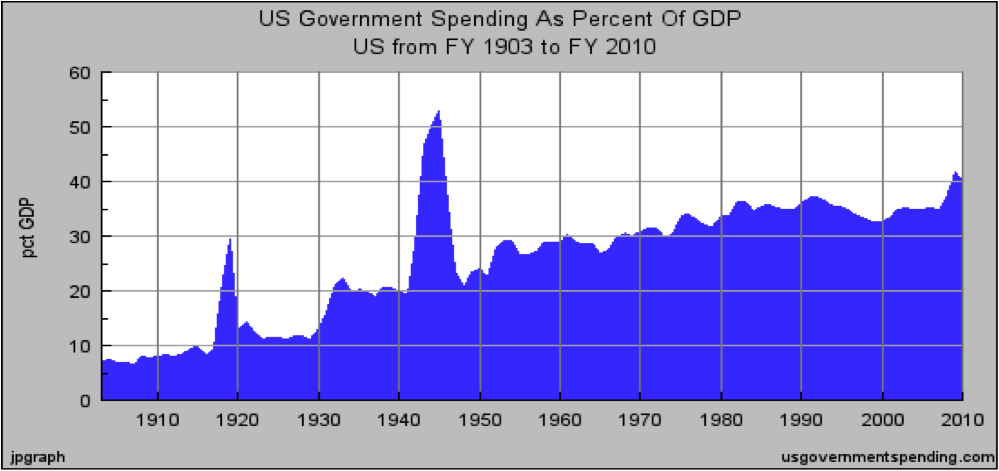

We prefer presenting facts in chart form, since it allows everyone the opportunity to form their own conclusion after studying the picture. Since 1903, total government spending, which includes spending by the Federal government and states, has risen from 8% to almost 40% of GDP in 2010.

This means for each $1 of GDP, government is controlling and determining how $.40 is spent. Since 1950, it has almost doubled, rising from 20% of GDP to 40% in 2010. The long term trend in government spending during the last 60 years has been up, and the share of our economy controlled by government has also risen proportionately. The cost of complying with the tax code and government regulation has been estimated to cost another 5% to 7% of GDP. The Federal Registry, which lists all the laws and regulations, is 70,000 pages. If these long term trends continue, government spending and compliance will soon exceed 50% of GDP. Is this what the founding fathers of our country and authors of the Constitution had in mind when they wrote about limited government? At what level of government spending and control is economic freedom compromised?

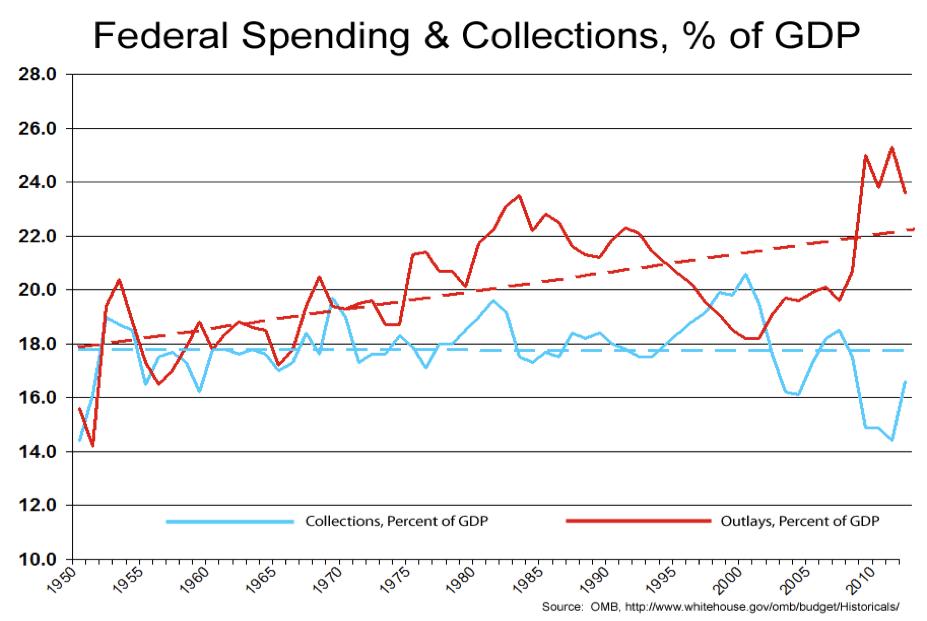

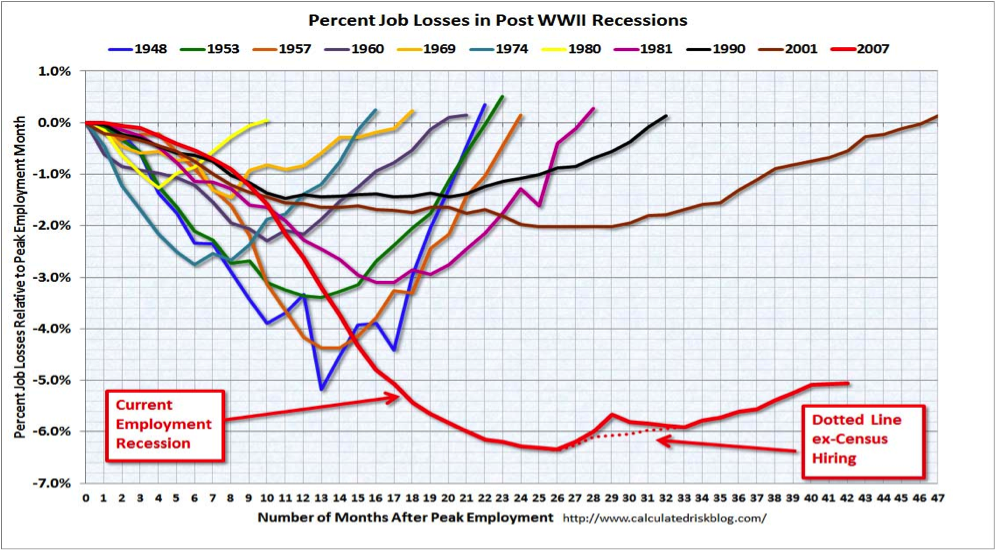

As the chart below illustrates, Federal spending as a percent of GDP has consistently exceeded Federal tax collections. The surplus in 2000 was the result of the tax increase in 1993, but more so from the capital gains tax windfall the government received as a result of the dot.com boom. Once technology stocks imploded in 2001 and 2002, tax collections plunged. Although the recession in 2001 was short and shallow, the recovery was not robust, and was often referred to as the ‘jobless’ recovery.

The Table below reveals a number of negative trends. The average annual budget deficit has been progressively increasing since 1950, rising from the 60 year average of -1.97% to the 10 year average of -3.41% since 2000.

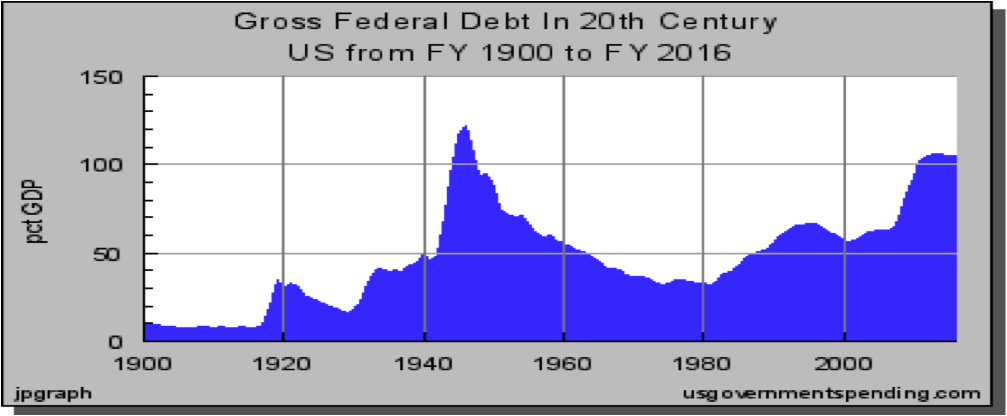

It is important to note that if the economy (GDP) is growing faster than the size of the budget deficit, total government debt as a percent of GDP will decline. During the 1950’s, 1960’s, and 1970’s, the long term average GDP growth was above the long term average of the annual budget deficit. This caused total Federal debt as a percent of GDP to fall from a World War II high of 120% to just 30% in 1980. However, since 1980, annual GDP growth has averaged +2.70%, while the budget deficit averaged -2.97%. As a result, total government debt rose from 30% of GDP in 1980 to 60% in 1995. Since GDP growth (+2.56%) exceeded the long term budget deficit average (-2.46%) between 1995 and 2000, total debt as a percent of GDP dipped until 2000. In the last 10 years, GDP has averaged an annual growth rate of 1.58%, while the budget deficit was averaging -3.41%. As a result of the financial crisis, the budget deficit exploded to almost 10% of GDP in 2009 and 2010, while GDP growth has stagnated. Government debt as a percent of GDP will exceed 90% of GDP by 2014, which will likely have a negative impact on growth in coming years. More on that a bit later.

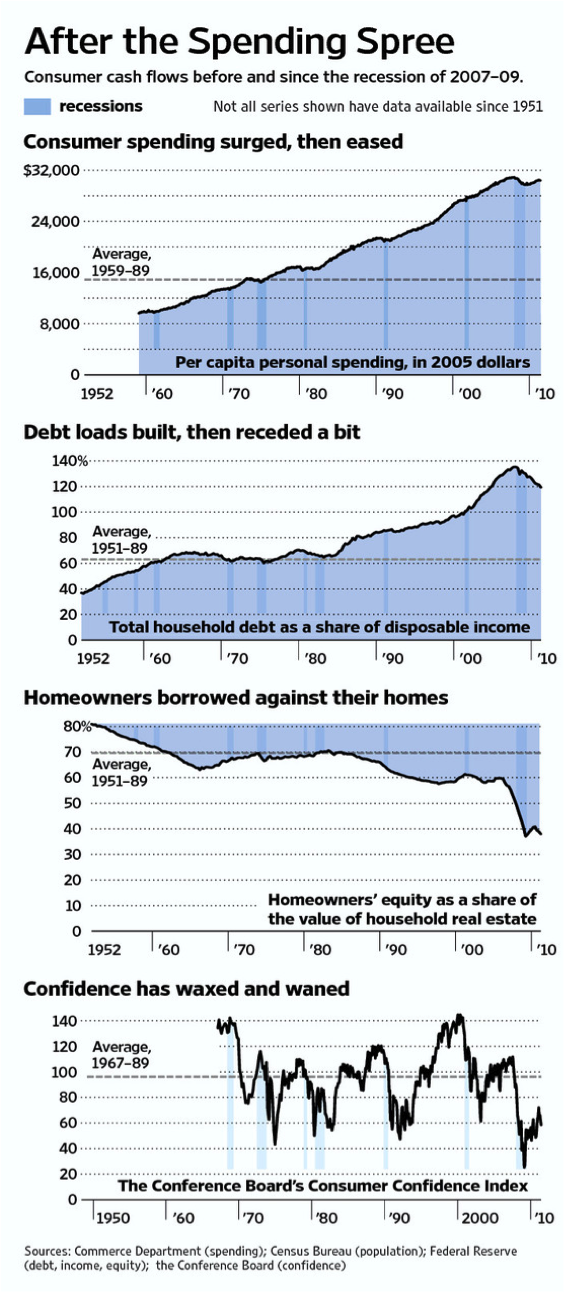

One of the more disturbing facts that becomes apparent when reviewing these statistics is the slowdown in annual GDP that has taken place since 1960, and especially since 1980. A significant portion of the growth in GDP since 1980 was financed by consumers taking on more debt. In 1984, household debt as a percent of disposable income was 62%, but by 2007 it was 137%. In 1980, the average homeowner’s equity was 71% of their home’s value. It is now down to 38%, after homeowners withdrew more than $1 trillion in home equity during the housing boom years, and the equity that simply evaporated as homes lost 30% of their value after the peak in 2006.

As consumers were piling on all this additional debt, they were buying more cars, furniture, clothes, jewelry, and fancy electronic gadgets. This debt financed demand boosted GDP above the level it would have been without the debt buying binge. In other words, the slowdown in GDP since 1980 would have been even more pronounced. Unfortunately, the lift the economy received from the increase in household debt from 1980 through 2007, will become a drag in coming years as consumers pay down debts or default. More than half of the decline in debt as a percent of disposable income has come from defaults.

Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff reviewed 800 years of history with a specific focus on financial crisis in 44 different countries in their book “This Time is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly”. They concluded that once a country’s total debt exceeded 90% of their GDP as a

Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff reviewed 800 years of history with a specific focus on financial crisis in 44 different countries in their book “This Time is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly”. They concluded that once a country’s total debt exceeded 90% of their GDP as a

result of a financial crisis, economic growth in the following decade was 1% lower than in the decade preceding the crisis. In the last 10 years, GDP has averaged an annual increase of 1.58%. The average since 1990 was 2.56%. Based on Reinhart and Rogoff’s research, we should expect GDP growth to average .58% to 1.56% for the decade between 2009 and 2019. Even if the economy does better than what history suggests is likely, and the U.S. manages to grow by 2% in coming years, growth of just 2% will have a profound impact on the annual budget deficit and total debt to GDP ratio. In order to lower our total debt to GDP ratio, the budget deficit will have to drop to less than 2%, from almost 10% today. As we have seen, the ratio of total debt to GDP only declines, if GDP growth is larger than the annual budget deficit. Secondly, tax revenue generated with the economy growing at 2% will be far less, than if growth averaged 3%. We suspect that whatever deal emerges in coming weeks or months it will likely assume GDP growth of 3% or higher for one simple reason. A higher assumed GDP rate will require smaller cuts in spending and smaller tax increases, to make it look like real progress is being made in bringing down the annual budget deficit and the percent of total debt to GDP. If Congress approves a budget that assumes GDP growth of much more than 2%, we will know that the proclaimed progress toward putting our fiscal house in order is a sham.

When household debt as a percent of disposable income was 62% in 1984, interest rates were well over 12%. (Chart pg. 5) As rates declined over the next two decades, it made it possible for consumers to add debt, since lower rates kept monthly payments manageable. With household debt now at 119% of disposable income, and interest rates at multi-generational lows, consumers won’t get any help from lower rates, as they did after 1984. They will have to pay off their debt the old fashion way – from earnings, and that’s not getting any easier. While the cost of living has increased 3.6% over the last year, wages have only gone up by 2.5%. The ongoing squeeze on disposable income is just one reason why consumer confidence remains mired at recessionary levels. (Chart pg. 5)

When household debt as a percent of disposable income was 62% in 1984, interest rates were well over 12%. (Chart pg. 5) As rates declined over the next two decades, it made it possible for consumers to add debt, since lower rates kept monthly payments manageable. With household debt now at 119% of disposable income, and interest rates at multi-generational lows, consumers won’t get any help from lower rates, as they did after 1984. They will have to pay off their debt the old fashion way – from earnings, and that’s not getting any easier. While the cost of living has increased 3.6% over the last year, wages have only gone up by 2.5%. The ongoing squeeze on disposable income is just one reason why consumer confidence remains mired at recessionary levels. (Chart pg. 5)

The ‘jobless recovery’ after the 2001 recession looks like a boom, when compared to job growth during the current recovery. It is going to take several more years to recover all the lost jobs, and that will have a large negative impact on our ability to reduce the budget deficit. With 5% of the labor force out of work, 16.2% of workers not finding full time employment, and the labor-force participation rate at a 28 year low of 64.1%, federal and state income taxes will remain weak and continue to stress budgets at all levels of government.

In addition, the cost of unemployment benefits and other assistance programs has soared since 2007, from $1.7 trillion to $2.3 trillion in 2010, an increase of 35%. Almost 20% of total personal income is coming from income transfers, according to a recent analysis by Moody’s Analytics. As extended jobless benefits expire for several million unemployed workers in coming months, Moody’s estimates that ‘unemployment’ income will decline by $37 billion by year end. There are 4.6 unemployed workers for each job opening, so finding a job won’t be easy.

Over the last 60 years, total government spending has increased as a percent of GDP from 20% to almost 40%. At a minimum, government at all levels will need to reduce the rate of increase in spending, and potentially freeze spending for a period of time, if we are to reduce the budget deficit and lower the ratio of total debt to GDP. However, reduced spending by government will slow economic growth, so the medicine will actually make the patient sicker in the short run.

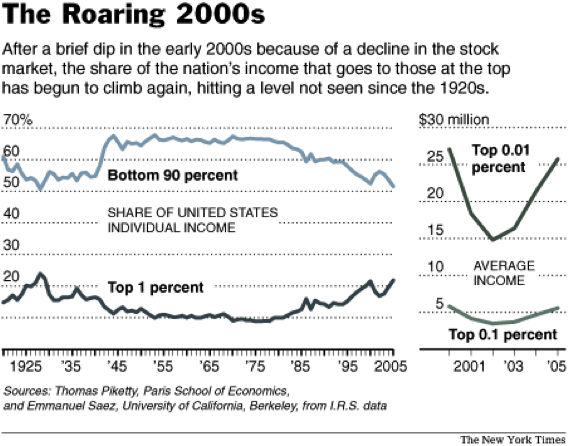

In the 1960’s, the average CEO was paid 35 times the average workers’ income. Last year, the CEO of a public company was paid 350 times the average worker’s pay. We don’t believe anyone is worth that much money to run a company. But, if the Board of Directors of a public company believes they must pay that much in compensation to attract ‘talent’, and shareholders don’t object, we see nothing wrong with it. At the same time, the gap in wages between the average working stiff and a CEO is just too large to ignore. The income for the top 1% reached 23.5% of total income in 2007, which is just a hair below the level reached in 1928. These income figures include capital gains and income from stock options. Although raising taxes on this elite group won’t raise that much in taxes, it will serve as an appropriate symbol. The austerity that must be imposed on government spending will prove a hardship on almost half of the 300 million citizens in this country. For most of those in the top 1% of income, higher taxes will be more of an inconvenience than an actual hardship.

In the 1960’s, the average CEO was paid 35 times the average workers’ income. Last year, the CEO of a public company was paid 350 times the average worker’s pay. We don’t believe anyone is worth that much money to run a company. But, if the Board of Directors of a public company believes they must pay that much in compensation to attract ‘talent’, and shareholders don’t object, we see nothing wrong with it. At the same time, the gap in wages between the average working stiff and a CEO is just too large to ignore. The income for the top 1% reached 23.5% of total income in 2007, which is just a hair below the level reached in 1928. These income figures include capital gains and income from stock options. Although raising taxes on this elite group won’t raise that much in taxes, it will serve as an appropriate symbol. The austerity that must be imposed on government spending will prove a hardship on almost half of the 300 million citizens in this country. For most of those in the top 1% of income, higher taxes will be more of an inconvenience than an actual hardship.

The top 20% of income earners represent 40% of total consumer spending, so raising taxes on the top 1% will result in less spending. Again, the right medicine will slow economic growth. As we have often said, there are no easy or quick fixes.

In 1961, President Kennedy set a goal to land an American astronaut on the moon within 10 years to address a long term threat to our security from the Soviet Union. The threat we face today is greater and more urgent than the risks we faced 50 years ago. We need to establish a clear long term goal, a definitive plan, and a specific timetable to accomplish it. We believe the goal should be to lower federal government spending to 19% of GDP over the next 10 years. Unlike landing an astronaut on the moon, we will be going to a place we’ve already been to, by returning federal spending to the average of the past 60 years. We can do this, and it is not draconian. We can reach our goal with reductions in spending and some tax increases. A ratio of $4 in spending cuts for each $1 in tax increase is the right balance, since spending has consistently outpaced tax increases since 1950. Just as landing a man on the moon Ewas fraught with risks and challenges, getting government spending down to 19% of GDP will also encounter unexpected challenges. Cutting government spending and raising taxes will lower economic growth, so we must proceed gradually, and make sure there are enough incentives to boost economic growth. Stronger economic growth will, over time, reduce the relative size of government, as long as we exercise better spending restraint. The assumed rate of GDP growth embedded in any deficit reduction plan will help us determine whether our leaders have the courage to stand up to those who finance their campaigns and make the unpopular decisions needed to get our country back on track. We’re skeptical, but would be delighted to be wrong in this assessment.

Europe

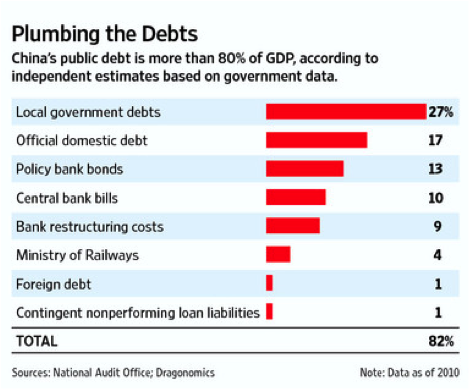

The health of the global economy also poses a risk to the United States, since the U.S. is not the only major industrialized country carrying a debt to GDP ratio above 90%. According to Eurostat and the CIA’s World Fact Book, Japan’s ratio is 197% and Italy’s is 120%. But there are a number of countries that are hovering just below the 90% threshold. France’s ratio of debt to GDP is 84%, Germany’s is 79%, and Britain’s is 77%. Within the EU, there are a number of smaller countries that are above the 90% benchmark. Greece leads the pack with a ratio of 153%, followed by Ireland at 114%, and Portugal and Belgium with 98%. China’s debt ratio is more than 80% of GDP according to independent estimates based on Chinese government data. In total, all these countries represent almost 60% of world GDP. This suggests that global growth could be .5% to 1% slower in the coming decade, as many countries are forced to lower the growth rate of government spending and hike taxes.

The health of the global economy also poses a risk to the United States, since the U.S. is not the only major industrialized country carrying a debt to GDP ratio above 90%. According to Eurostat and the CIA’s World Fact Book, Japan’s ratio is 197% and Italy’s is 120%. But there are a number of countries that are hovering just below the 90% threshold. France’s ratio of debt to GDP is 84%, Germany’s is 79%, and Britain’s is 77%. Within the EU, there are a number of smaller countries that are above the 90% benchmark. Greece leads the pack with a ratio of 153%, followed by Ireland at 114%, and Portugal and Belgium with 98%. China’s debt ratio is more than 80% of GDP according to independent estimates based on Chinese government data. In total, all these countries represent almost 60% of world GDP. This suggests that global growth could be .5% to 1% slower in the coming decade, as many countries are forced to lower the growth rate of government spending and hike taxes.

The debt crisis in Europe will get worse. Either Greece will eventually choose to leave the EU, or European banks will have to forgive about half of the Greek debt they are holding. This will require many European banks to raise more capital. We can’t imagine that either of these outcomes will not result in another shakeout of the global financial system. Our bet is that it will happen before March 2012.

China

In the second quarter, China’s GDP dipped to 9.5% from 9.7% in the first quarter. More importantly, on June 30 the China Federation of Logistics and Purchasing said its monthly purchasing managers index fell to 50.9 in June from 52 in May, the slowest pace in 28 months. Despite the modest slowing in economic growth, consumer prices rose 6.4% in June, the highest in three years. On July 6, the People’s Bank of China increased its one-year lending rate to 6.56% from 6.31%. If China’s purchasing managers index dips below 50, this could be the last rate increase.

In the last two years, Chinese state-owned banks loaned $3 trillion to stimulate growth in the wake of the financial crisis in 2008. This amounts to 60% of China’s GDP. It is unlikely that bankers in China will prove any smarter than their U.S. counterparts. This run away lending boosted land values, real estate values, and no doubt expanded China’s export capacity. If global growth is slower in coming years, China will have an excess capacity problem as demand from the U.S. and Europe proves weaker than in the past. Given the run up in real estate values, China will likely have to deal with its own version of a deflating real estate bubble. Moody’s Investor Services estimates non-performing loans could amount to 8% to 12% of total loans. At the end of 2010, the ‘official’ non-performing rate was just 1.14%. Sometime in 2012, China’s economy will slow even more, and we will be reading stories about banking problems.

In the last two years, Chinese state-owned banks loaned $3 trillion to stimulate growth in the wake of the financial crisis in 2008. This amounts to 60% of China’s GDP. It is unlikely that bankers in China will prove any smarter than their U.S. counterparts. This run away lending boosted land values, real estate values, and no doubt expanded China’s export capacity. If global growth is slower in coming years, China will have an excess capacity problem as demand from the U.S. and Europe proves weaker than in the past. Given the run up in real estate values, China will likely have to deal with its own version of a deflating real estate bubble. Moody’s Investor Services estimates non-performing loans could amount to 8% to 12% of total loans. At the end of 2010, the ‘official’ non-performing rate was just 1.14%. Sometime in 2012, China’s economy will slow even more, and we will be reading stories about banking problems.

Dollar

In our May letter we recommended going long the Dollar via its ETF (UUP) at $21.56, and last month recommended holding the position. Since early May, the Dollar appears to be forming a rising triangle. This type of technical formation typically shows up prior to one final move, before a lasting trend reversal takes hold. This suggests UUP will drop below the May 4 low at $20.84. We suggest adding to the UUP position at $20.50. If we are correct, the coming low will mark an intermediate low that should result in a rally of more than 10% in coming months.

Bonds

We continue to believe that the yield on the 10-year Treasury bond will remain range bound between 2.6% and 3.65%. With the yield currently hovering near 3.0%, it is in the middle of the range. Given our outlook on the economy, we don’t anticipate the Federal Reserve raising rates anytime soon. We would be a buyer if yields backed up to 3.5%, and a seller if it drops to 2.7%.

Gold

Gold made a new all-time high this week, but as we expected, silver has not, nor have the gold stock indexes, as measured by the XAU and HUI. A number of momentum measures on Gold are making lower peaks, when compared to the May high at $1,578.00. Last month, we suggested aggressive traders establish a small short position at $1,550, and add to it at $1,587.00. We expect a higher high in gold, before a pullback to $1,450-$1,500 takes hold.

Stocks

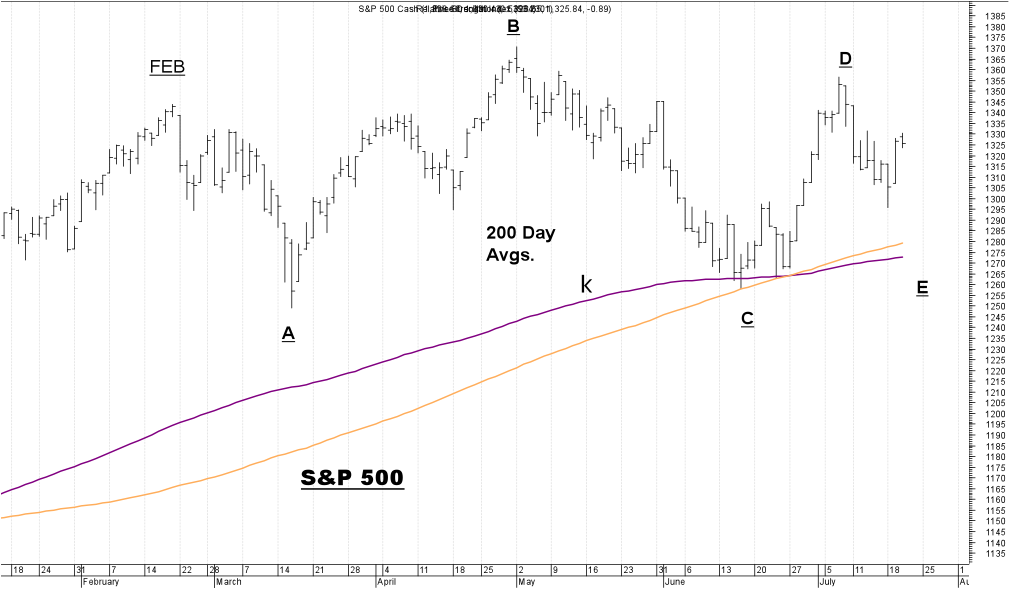

It appears that the S&P is tracing out a 5 point triangle, as denoted by the A, B, C, D, and E on the chart below. While not necessary, there may be one more dip below Monday’s low at 1295, before a substantial rally above 1,370 commences. If this analysis is correct, the 200 day averages (simple and exponential) should provide support, and the S&P should not close below 1258. In the June 12 Special Update, we recommended taking a half position in the S&P 500 ETF SPY, which opened at $127.89 on June 13. Add to this position, if the S&P drops below 1,290, and raise the stop from 1,230 to a close below 1,250, which should translate to roughly $125.00 on SPY.

Macro Tides

What's been said:

Discussions found on the web: