Frederick Sheehan is the co-author of Greenspan’s Bubbles: The Age of Ignorance at the Federal Reserve.

Frederick Sheehan is the co-author of Greenspan’s Bubbles: The Age of Ignorance at the Federal Reserve.

His new book, Panderer for Power: The True Story of How Alan Greenspan Enriched Wall Street and Left a Legacy of Recession, was published by McGraw-Hill in November 2009. He was Director of Asset Allocation Services at John Hancock Financial Services in Boston. In this capacity, he set investment policy and asset allocation for institutional pension plans.

~~~

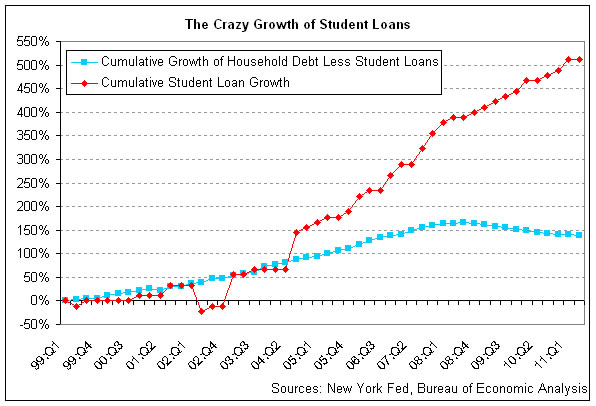

The Atlantic magazine has illustrated the unsustainable growth of student debt in the chart below. In David Indiviglio’s August, 18, 2011, article, “Student Loans Have Grown 511% Since 1999,” the author notes: “Obviously the number of students didn’t grow by 511%. So why are education loans growing so rapidly? One reason could be availability. The government’s backing lets credit to students flow very freely…. [U]niversities are raising tuition aggressively since students are willing to pay more through those loans.”

Indiviglio concentrates his attention on the future problem for the students, though that is secondary, except, of course, to the students in hock and out-of-luck lenders. Colleges and universities in the United States are a short sale. Great Courses are a long. The latter is the model to ponder.

The number of colleges will plummet. This is due to the loss of nerve, confidence, substance, direction, integrity – will that do? – of teaching in America. Just look at that chart: what a picture of insatiable greediness and self-indulgence among the colleges. No thought to the unbearable debt deposited on their students.

Angelo Mozilo, the grand poobah of subprime mortgages, is correctly vilified for coaxing financial naives into debtors’ prison, but the same tactics by the education establishment goes unremarked. In another Atlantic article, “The Debt Crisis at American Colleges,” authors Andrew Hacker and Claudia Dreifus write: “[C]olleges have embraced a host of extraneous activities – from obscure sports to overseas centers – and tacked most or all of their tabs onto students’ bills. Unlike businesses, which cut losing operations, colleges simply hike their tuitions.” Will former Harvard Professor Elizabeth Warren’s ill-defined federal agency, watchdog over slatternly marketing hoaxes by financial institutions, apply the same standards to deceptive, college sales practices?

A century ago, John Jay Chapman, Harvard alum, was a pain-in-the-neck to Harvard College President Charles William Eliot. He tried to sack the president. In 1909, Chapman wrote that his college had diluted its resolve to teach the truth: “The men who control Harvard to-day are business men, running a large department store…. Devising new means of expansion, new cash registers and credit systems – systems for increasing their capital and the volume of trade….The wonderful ability of the American business man for organization is now at work consolidating the Harvard graduates into a corps which seems to have the same sort of enthusiasm about itself as a base-ball team…. (This is excerpted from “The Hundred Year Bubble,” a dissertation originally published in the January 2010 issue of the Gloom, Boom & Doom Report on America’s unwillingness to set limits over the past century, and the parallel inflation of money, self-improvement, self-delusion, and self-gratification.)

Chapman’s alarm may be difficult to understand today, but he had the advantage of living during a sharp break in the then-nearly-300-year history of Harvard College: before and after it took the low road. Eliot was an early exemplar of the “New Education” thesis that sought a “universal utility” in American education. This inflation of mission and of human potential, captured in Eliot’s substitution of vocabulary for thought, is collapsing.

Others also rued the dangerous downgrading of the American mind at the universities. In 1908, Albert Straus, then partner at the investment firm of J.W. Seligman and Company, told a Columbia University audience: “[W]e are slaves to our phrases; what begins by being a metaphor ends by dominating our thinking…[W]e often reason about these matters as though the pictures that our words call up were real.” And Straus never saw MTV.

Colleges today have set many missions for themselves, not many of which are in the interests of their students. They disguise their reluctance to teach with slogans and images: “empowering students to achieve professional and personal success in dynamic careers and in a diverse global society by providing a comprehensive and supportive educational experience, fostering academic integrity, and encouraging lifelong learning.” (Berkeley College, Boston) Only by carrying the imprimatur of a college, or of a government bureaucracy (really, one in the same, they are slaves to each other), does the public accept such a pile of flotsam as making sense. (Yes: Bernanke and his fellow imposters.)

A globally-known investor wrote to me after “Scarlett O’Hara’s Risk-Free Rate” that Harvard is finished and will be insolvent. The collapse of America’s colleges, and of the primary- and secondary-school farm systems, will probably be a good thing overall, difficult as it will be to understand during the unfolding: It may clear out the zoo.

In the July 2011 edition of the

Gloom, Boom & Doom Report, Marc Faber quoted a study from the Goldwater Institute that found between “1993 and 2007, the number of full-time administrators per 100 students at America’s leading universities grew by 39 percent, while the number of employees engaged in teaching, research, or service only grew by 18 percent.”

In the Summer 2011 edition of City Journal, Heather MacDonald writes: “This past academic year, for example, a Bowdoin College student interested in American history courses could have taken ‘Black Women in Atlantic New Orleans,’ ‘Women in American History, 1600-1900,’ or ‘Lawn Boy Meets Valley Girl: Gender in the Suburbs,’ but if he wanted to take a course in American political history, the colonial and revolutionary periods, or the Civil War, he would have been out of luck.”

Noteworthy is the larger topic Mac Donald discusses in “Great Courses, Great Profits.” A company called Great Courses is making gobs of money selling recorded lectures by college professors who teach “Plato, Aristotle, Cicero, Paul, Erasmus, Galileo, Bacon, Descartes, Hobbes, Spinoza, Dante, Chaucer, Spenser, Shakespeare, Cervantes, Milton, Pope, Swift, Goethe, and others…” This may not be materially different from the lectures John Jay Chapman attended in the 1870s. Those who pay Great Courses receive no degree, no padding to their resume, no Delta House invitations, no country-club dormitory suite, no indulgent, grief-counseling administrators, and no future business network.

Macdonald goes on to write that college faculties wring their hands because the curriculum has been “problemetized.” There is some resistance to such courses as “Queering the Alamo.”

“My dear James,” wrote Chapman in 1907 to his friend, Harvard professor William James (The Varieties of Religious Experience), “Eliot has boomed and boomed – till we think it’s the proper way to go on. He must, or lose foothold. Well, why not a man who does not boom? Is boom the best thing in life? Is it all boom? Is there now and to be nothing ever but boom, boom, boom? Is there not something that operates without money – not anywhere?”

The Spring 2011 edition of The Trinity Reporter, alumni magazine of Trinity College (Connecticut), includes a full-page pitch to alums under the picture of a 2004 graduate (name withheld, to spare his family further publicity for this embarrassing incident) screaming like Janis Joplin and tearing his white shirt, blue blazer, and blue-and-gold school tie off to reveal a muscle-bound chest covered with a gray “Trinity” gym shirt. “Blue and Gold Is In Your Blood,” shrieks the copy: “Let’s keep that competitive spirit alive and show our rivals why Trinity College is among the Top Ten schools in alumni giving participation in the country.”

There is really no need to comment on the consummation of Chapman’s foresight. The fulfillment of Chapman’s letter to Dear James has regressed to the least common denominator.

What might we gain from Sherman’s march through the academy? A taming of the zoo. Twenty years ago the author and critic Harold Bloom (The Western Canon, 1994) was interviewed by the Paris Review. Quoting Bloom: “I watch MTV endlessly.” This enemy of “The School of Resentment” – feminist literary critics, new historicists, poststructuralists, deconstructionists, semioticians, laconists, and poetry slamists – saw MTV as the real vision of what this country desires: “no matter how many [performers] are on the screen, not one of them feels free except in total self-exaltation.” Time to short March Madness?

Source:

Harvard Deconstructed: The Taming of the Zoo

by Frederick Sheehan, August 31, 2011

What's been said:

Discussions found on the web: