That the rich get richer and the poor get poorer. At least, that is what most people believe.

That cliché is not quite accurate. The data on this subject, as detailed by the CBO and reflected in the charts below, reveals that over the past three decades, the poor got a little bit richer, the rich got a lot richer, and the most rich got phenomenally richer.

That may not fit on a bumper sticker, but it is the simple fact.

We learn these details from a newly released report on real (inflation-adjusted) average household income in the United States from the non-partisan Congressional Budget Office, titled Trends in the Distribution of Household Income Between 1979 and 2007.

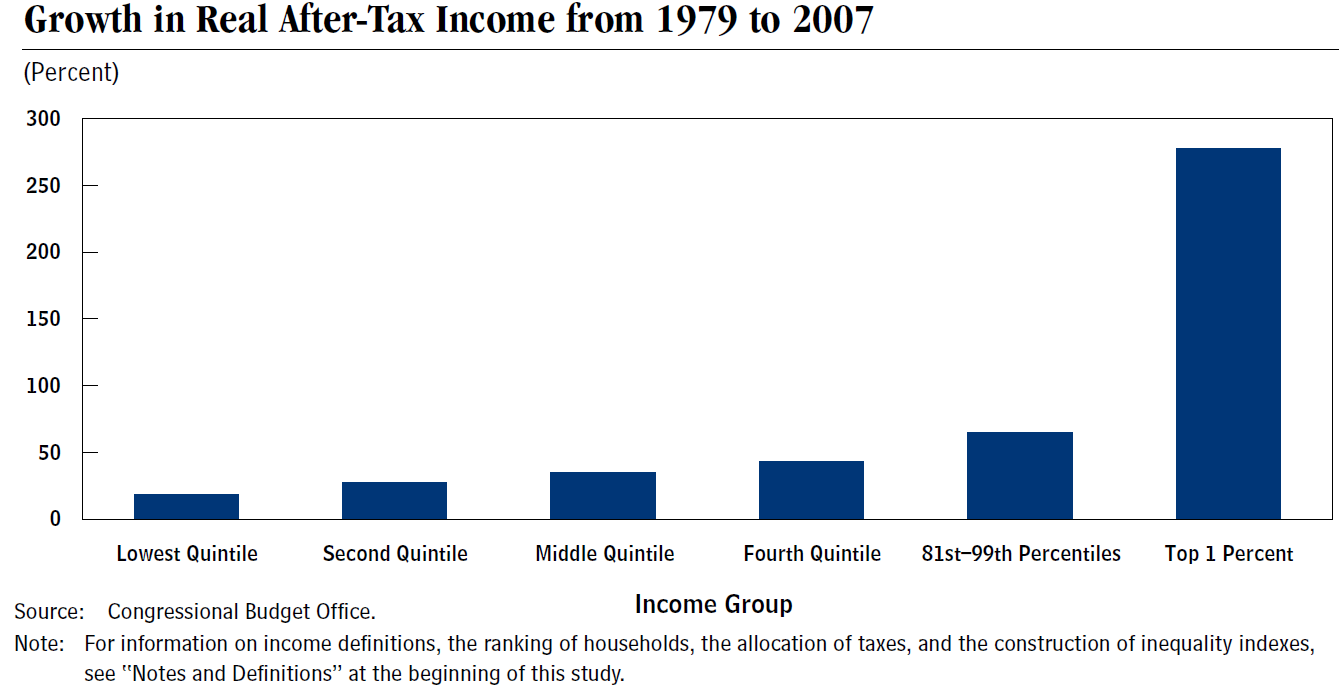

The rich got richer — almost three times as rich — over that time period:

For the 1 percent of the population with the highest income, average real after-tax household income grew by 275 percent between 1979 and 2007 (see Summary Figure 1).

>

>

The very rich — the top 1% — captured the lionshare of the growth of total market income:

As a result of that uneven growth, the share of total market income received by the top 1 percent of the population more than doubled between 1979 and 2007, growing from about 10 percent to more than 20 percent. Without that growth at the top of the distribution, income inequality still would have increased, but not by nearly as much. The precise reasons for the rapid growth in income at the top are not well understood, though researchers have offered several potential rationales, including technical innovations that have changed the labor market for superstars (such as actors, athletes, and musicians), changes in the governance and structure of executive compensation, increases in firms’ size and complexity, and the increasing scale of financial-sector activities.

>

>

And as we showed the other day (see Forget the top 1% — Look at the top 0.1% and PPT presentation), the income inequality was skewed to an even greater degree amongst that top 1% — the top 0.1% and the much wealthier 0.01% is where all the big bucks are.

This matters a great deal — but not for the silly political reasons you have been led to think. No, its not about class warfare. No, its not about redistributing the wealth.

The reason this matters is quite simple: Healthy societies have modest, but not extreme wealth and income inequalities. There are inequalities because not everyone has the same skills and capabilities, and some inequality in wealth and income provides an incentive system.

However, massive, widely disparate economic inequality has historically led to bad — and in some cases, extremely bad — outcomes. It contributes to social unrest, excessive political populism, and mob violence.

I write this as someone who, due to a fortuitous combination of luck and work, developed a skill set that is highly valued by modern society. This is in part to an accident of birth, to have an excellent education, to some serendipity. Overcoming some adversity didn’t hurt; figuring out how to turn some deficits to an advantage was hugely beneficial. Thus, I find myself in that top 1% economically; but I know deep down in my soul that if I was born 100 years earlier — and maybe even 30 years earlier — I would not have been. This makes me acutely aware of the risks and dangers of our current wide disparity of wealth and income.

Healthy societies allow their citizens to have a realistic chance at fulfilling their potential. This is done through a combination of economic freedom, enforcement of laws and contracts, legitimate democratic elections, basic education for its citizens, tax fairness, regulatory oversight of influential corporations an other entities, and the institutional value of protecting individual liberty.

Where is the United States falling short?

~~~

Summary of CBO paper after the jump; full paper here.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

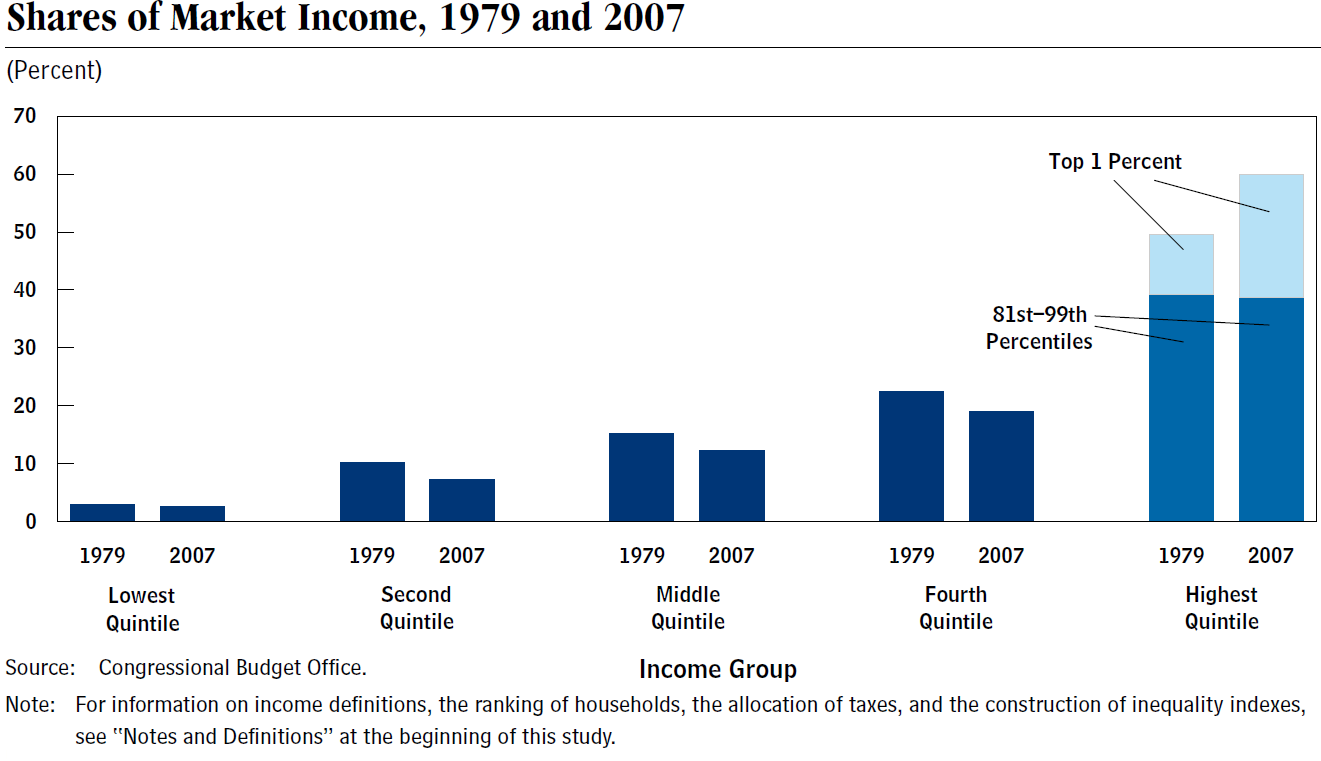

Increased Concentration of Market Income

The major reason for the growing unevenness in the distribution of after-tax income was an increase in the concentration of market income (income measured before government transfers and taxes) in favor of higher income households; that is, such households’ share of market income was greater in 2007 than in 1979. Specifically, over that period, the highest income quintile’s share of market income increased from 50 percent to 60 percent (see Summary Figure 2). The share of market income for every other quintile declined. (Each quintile contains one-fifth of the population, ranked by adjusted household income.) In fact, the distribution of market income became more unequal almost continuously between 1979 and 2007 except during the recessions in 1990–1991 and 2001.

Two factors accounted for the changing distribution of market income. One was an increase in the concentration of each source of market income, which consists of labor income (such as cash wages and salaries and employer paid health insurance premiums), business income, capital gains, capital income, and other income. All of those sources of market income were less evenly distributed in 2007 than they were in 1979.

The other factor leading to an increased concentration of market income was a shift in the composition of that income. Labor income has been more evenly distributed than capital and business income, and both capital income and business income have been more evenly distributed than capital gains. Between 1979 and 2007, the share of income coming from capital gains and business income increased, while the share coming from labor income and capital income decreased.

Those two factors were responsible in varying degrees for the increase in income concentration over different portions of the 1979–2007 period. In the early years of the period, market income concentration increased almost exclusively as a result of an increasing concentration of separate income sources. The increased concentration of labor income alone accounted for more than 90 percent of the increase in the concentration of market income in those years. In the middle years of the period, an increase in the concentration within each income source accounted for about one-half of the overall increase in market income concentration; a shift to more concentrated sources explains the other half. In the later years, an increase in the share of total income from more highly concentrated sources, in this case capital gains, accounted for about four-fifths of the total increase in concentration. Over the 1979–2007 period as a whole, an increasing concentration of each source of market income was the more significant factor, accounting for four-fifths of the increase in market income concentration.

Income at the Very Top of the Distribution

The rapid growth in average real household market income for the 1 percent of the population with the highest income was a major factor contributing to the growing inequality in the distribution of household income between 1979 and 2007. Average real household market income for the highest income group nearly tripled over that period, whereas market income increased by about 19 percent for a household at the midpoint of the income distribution. As a result of that uneven growth, the share of total market income received by the top 1 percent of the population more than doubled between 1979 and 2007, growing from about 10 percent to more than 20 percent. Without that growth at the top of the distribution, income inequality still would have increased, but not by nearly as much. The precise reasons for the rapid growth in income at the top are not well understood, though researchers have offered several potential rationales, including technical innovations that have changed the labor market for superstars (such as actors, athletes, and musicians), changes in the governance and structure of executive compensation, increases in firms’ size and complexity, and the increasing scale of financial-sector activities.

The composition of income for the 1 percent of the population with the highest income changed significantly from 1979 to 2007, as the shares from labor and business income increased and the share of income represented by capital income decreased. That pattern is consistent with a longer-term trend: Over the entire 20th century, labor income has become a larger share of income for high income taxpayers, while capital income has declined as a share of their income.

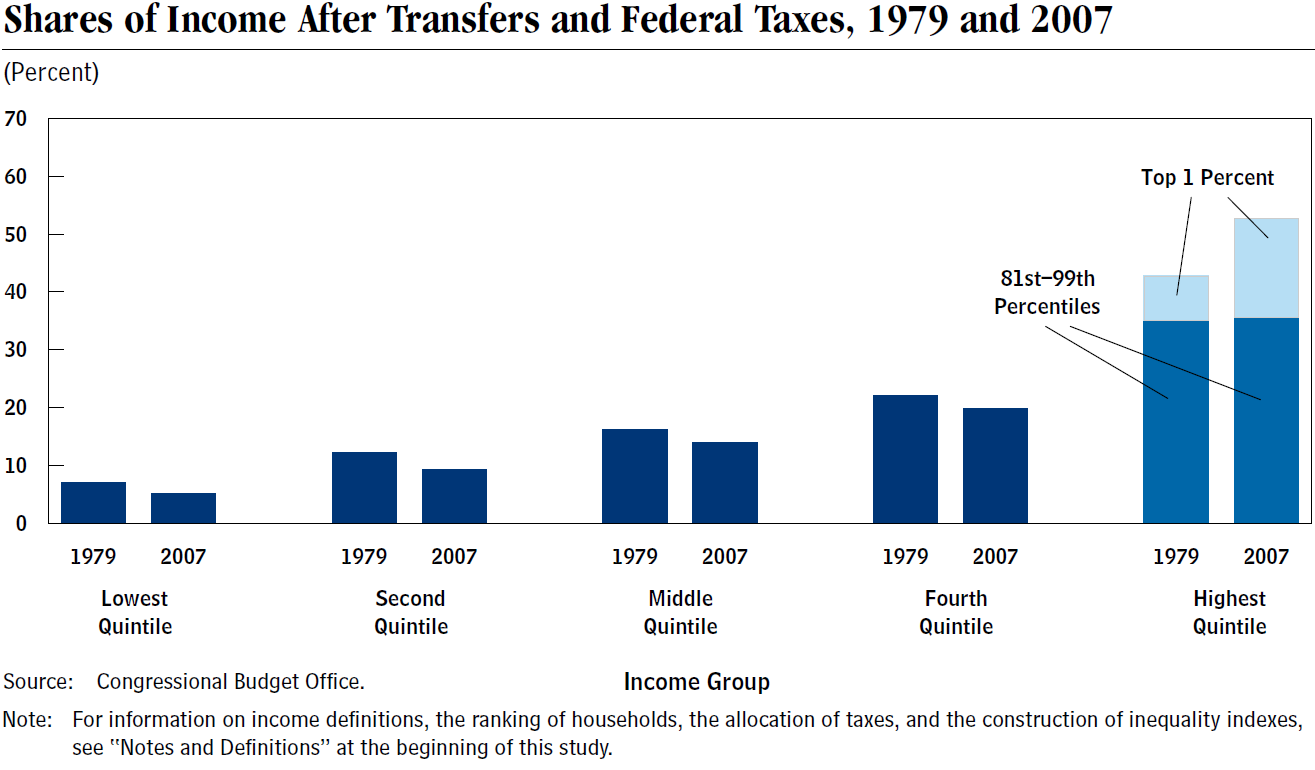

Increased Concentration of After-Tax Income

As a result of those changes, the share of household income after transfers and federal taxes going to the highest income quintile grew from 43 percent in 1979 to 53 percent in 2007 (see Summary Figure 3). The share of after-tax household income for the 1 percent of the population with the highest income more than doubled, climbing from nearly 8 percent in 1979 to 17 percent in 2007. The population in the lowest income quintile received about 7 percent of after-tax income in 1979; by 2007, their share of after-tax income had fallen to about 5 percent. The middle three income quintiles all saw their shares of after-tax income decline by 2 to 3 percentage points between 1979 and 2007.

~~~

Source:

Congress Of The United States congressional Budget Office

Trends in the Distribution of Household Income Between 1979 and 2007

October 2011

Hat tip Neatorama, October 26, 2011

What's been said:

Discussions found on the web: