“What’s happened is that, almost overnight, we’ve switched from democracy in real-property recording to oligarchy in real-property recording. There was no court case behind this, no statute from Congress or the state legislatures. It was accomplished in a private corporate decision. The banks just did it.”

-Christopher Peterson, a law professor at the University of Utah, on the “wholesale transfer of mortgages to a privatized database” and why it’s no coincidence more Americans are being foreclosed upon than any time since the Great Depression.

>

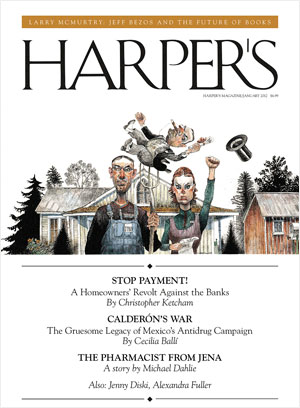

The quote above is from an article in the January 2012 Harper’s. It’s ostensibly about the ongoing battle between Homeowners and Bankers (PDF is online at Scribd, Think Tank, but not for long).

The quote above is from an article in the January 2012 Harper’s. It’s ostensibly about the ongoing battle between Homeowners and Bankers (PDF is online at Scribd, Think Tank, but not for long).

The print edition is illustrated with the artwork of Amy Casey (Housing as a Recurring Dream (Nightmare), previously showcased here)

What makes the article so remarkable is it has one of the most powerful anti-MERS arguments I have ever read in the mainstream media. In addition to the quote above, there is this:

At the heart of the clouded-title problem is a Virginia-based company, recently much in the national news, called Mortgage Electronic Registration Systems. MERS was created in 1995 as a privately held venture of the major mortgage-finance operators, chief among them the government-sponsored mortgaging entities Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Its stated purpose was to manage a confidential electronic registry for the tracking of the sale of mortgage loans between lenders, which could now place loans under MERS’s name to avoid filing the paperwork normally required whenever mortgage assignments changed hands. No longer would the traffickers in mortgages have to document their transactions with county clerks, nor would they have to pay the many and varied courthouse fees for such transactions. Instead, MERS was listed in local recording offices as the “mortgagee of record,” the in-name-only owner, a so-called nominee for the lender, so that MERS would effectively “own” the loan where the public record was concerned, while the lenders traded it back and forth.

This centralized database facilitated the buying and selling of mortgage debt at great speed and greatly reduced cost. It was a key innovation in expediting the packaging of mortgage-backed securities. Soon after the registry launched, in 1999, the Wall Street ratings agencies pronounced the system sound. “The legal mechanism set up to put creditors on notice of a mortgage is valid,” as was “the ability to foreclose,” assured Moody’s. That same year, Lehman Brothers issued the first AAA-rated mortgage-backed security built out of MERS mortgages. By the end of 2002, MERS was registering itself as the owner of 21,000 loans every day. Five years later, at the peak of the housing bubble, MERS registered some two thirds of all home loans in the United States.

Without the efficiencies of MERS there probably would never have been a mortgage-finance bubble.

After the housing market collapsed, however, MERS found itself under attack in courts across the country. MERS had singlehandedly unraveled centuries of precedent in property titling and mortgage recordation, and judges in state appellate and federal bankruptcy courts in more than a dozen jurisdictions—the primary venues where real estate cases are decided— determined that the company did not have the right to foreclose on the mortgages it held.

In 2009, Kansas became one of the first states to have its supreme court rule against MERS. In Landmark National Bank v. Boyd A. Kesler, the court concluded that MERS failed to follow Kansas statute: the company had not publicly recorded the chain of title with the relevant registers of deeds in counties across the state. A mortgage contract, the justices wrote, consists of two documents: the deed of trust, which secures the house as collateral on a loan, and the promissory note, which indebts the borrower to the lender. The two documents were sometimes literally inseparable: under the rules of the paper recording system at county court-houses, they were tied together with a ribbon or seal to be undone only once the note had been paid off. “In the event that a mortgage loan somehow separates interests of the note and the deed of trust, with the deed of trust lying with some independent entity,” said the Kansas court, “the mortgage may become unenforceable.”

MERS purported to be the independent entity holding the deed of trust. The note of indebtedness, however, was sold within the MERS system, or “assigned” among various lenders. This was in keeping with MERS’s policy: it was not a bank, made no loans, had no money to lend, and did not collect loan payments. It had no interest in the loan, only in the deed of trust. The company—along with the lenders that had used it to assign ownership of notes—had thus entered into a vexing legal bind. “There is no evidence of record that establishes that MERS either held the promissory note or was given the authority [to] assign the note,” the Kansas court found, quoting a decision from a district court in California. Not only did MERS fail to legally assign the notes, the company presented “no evidence as to who owns the note.”

Similar cases were brought before courts in Idaho, Massachusetts, Missouri, Nevada, New York, Oregon, Utah, and other states. “It appears that every MERS mortgage,” a New York State Supreme Court judge recently told me, “is defective, a piece of crap.” The language in the judgments against MERS became increasingly denunciatory. MERS’s arguments for standing in foreclosure were described as “absurd,” forcing courts to move through “a syntactical fog into an impassable swamp.”

(emphasis added)

I was so thrilled with this piece, I subscribed to Harper’s Magazine thru Amazon ($10)

>

Source:

Stop payment! A homeowners’ revolt against the banks

Christopher Ketcham

Harpers, January 2012

http://harpers.org/archive/2012/01/0083752

What's been said:

Discussions found on the web: