Why ECRI’s Recession Call Stands

Lakshman Achuthan & Anirvan Banerji

March 15, 2012

>

Many have questioned why, in the face of improving economic data, ECRI has maintained its recession call. The straight answer is that the objective economic indicators we monitor, including those we make public, give us no other choice.

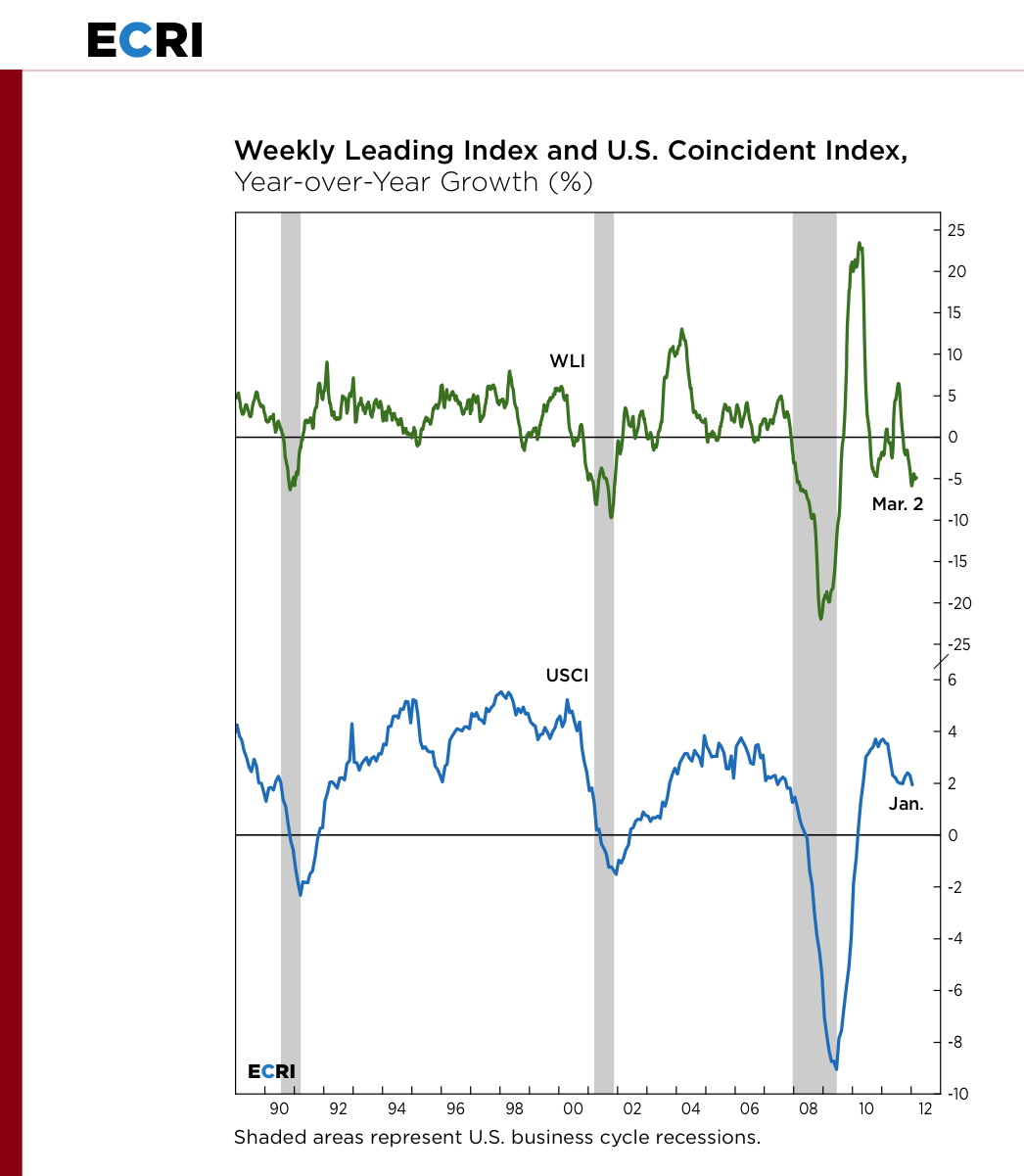

Let’s start with the current state of the economy. A couple of weeks ago, we publicly highlighted ECRI’s U.S. Coincident Index (USCI). It’s important to understand that the USCI isn’t a random concoction of data, but rather the gold standard for measuring current economic growth, as it summarizes the key coincident economic indicators used to determine the official start and end dates of U.S. recessions; namely, the broad measures of output, employment, income and sales. So when USCI growth is in a downturn (bottom line in chart), it’s an authoritative indication that overall U.S. economic growth is actually worsening, not reviving.

In contrast to the 3% GDP growth widely reported for the latest quarter, year-over-year growth in GDP, after peaking at 3½% in Q3/2010, has basically flatlined around 1½% for the last three quarters. Broad sales growth has followed a similar pattern, while the growth rates of personal income and industrial production have dropped to their lowest readings since the spring of 2010.

The exception to this weakening pattern is year-over-year payroll job growth, which continued to improve through January, and was essentially flat in February. However, the empirical record shows that job growth typically turns down after downturns in consumer spending growth, not the other way around. Because consumer spending growth remains in a cyclical downturn, we expect job growth to start flagging in the coming months. But the point remains that the USCI, which summarizes the definitive coincident economic indicators – including jobs – indicates declining growth in the U.S. economy.

How about forward-looking indicators? We find that year-over-year growth in ECRI’s Weekly Leading Index (WLI) remains in a cyclical downturn (top line in chart) and, as of early March, is near its worst reading since July 2009. Close observers of this index might be understandably surprised by this persistent weakness, since the WLI’s smoothed annualized growth rate, which is much better known, has turned decidedly less negative in recent months. The unusual divergence between these two measures of growth underscores a widespread seasonal adjustment problem that economists have known about for some time.

>

WLI and USCI y-o-y growth

>

Most data, both public and private, are seasonally adjusted. But the nature of the Great Recession seems to have had an unexpected impact on the statistical seasonal adjustment algorithms that are hard-wired to detect when the seasonal patterns evolve and change over the years. This is normally a good thing, but when the economy fell off a cliff in Q4/2008 and Q1/2009, it was partly interpreted by these procedures as a lasting change in seasonal patterns. So, according to these programs, data from Q4 and Q1 would be expected thereafter to be relatively weak, and therefore automatically adjusted upwards. Our due diligence on this subject indicates a widespread problem, resulting in many recent economic headlines being skewed to the upside.

However, we have no way to objectively measure the extent of these problems – either the upward bias for Q4 and Q1 or the downward bias for Q2 and Q3. Fortunately, year-over-year growth rates are naturally less susceptible to these seasonal issues because they involve comparisons to the same period a year earlier that is likely to be skewed the same way. In contrast, smoothed annualized growth rates, which we have traditionally preferred, presume proper seasonal adjustment. While the extent of the seasonal problem will be debated, monitoring year-over-year growth rates is a matter of simple prudence at this juncture not only for ECRI’s indexes but also for other economic data.

In the chart, please note the one-to-one correspondence between the cyclical swings in the year-over-year growth rates of the WLI and USCI since the Great Recession. Both surged initially, only to roll over, pop up briefly, and then turn down once again. It is notable that the WLI, which is sensitive to the prices of risk assets that have been supported by massive worldwide liquidity injections, has hardly been swayed from its recessionary trajectory. In spite of the efforts of monetary policy makers, actual U.S. economic growth has slowed, while WLI growth has barely budged from a two-and-a-half-year low.

The bigger question is, can unprecedented, concerted global monetary policy action repeal the business cycle? The objective coincident and leading indexes that we have always monitored are still telling us that it cannot.

———————-

Data source for Coincident Index (XLSX)

What's been said:

Discussions found on the web: