Australia: Running Out of Luck Down Under

John Mauldin

August 27, 2012

While it is summer in the Northern Hemisphere, it is winter “down under.” Today we turn our attention to Australia. In Endgame, Jonathan Tepper and I devoted a full chapter to talking about the problems we saw looming in Australia, and for that we have taken some heat! What’s not to like about the Land of Oz? In our view, it might be the bubbles that are building. I asked Jonathan to update us on Australia, and in today’s Outside the Box he gives us an in-depth look. Let me quote from a point near the end, in case you might decide to look just at the summary:

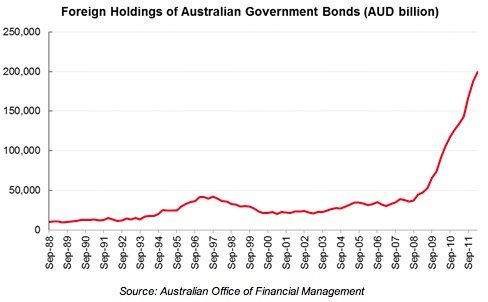

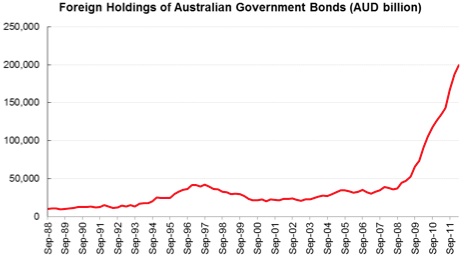

“The search for yield and essentially diversification out of sovereign debt markets in distress has led to a surge in the foreign holdings of Australian government bonds. According to the latest data from the Australian Office of Financial Management, the total foreign ownership of Australian government bonds now stands at 80% of the total outstanding debt, up from 60% in 2006.

“Although this may sound high, government debt to GDP in Australia is low, at 30% (although is up from 16% in 2008). This low ratio is a result of running a budget surplus for most of the last 15 years. But, even though the situation looks good optically, the fact of the matter is Australia would have to backstop its banks in the event of a crisis, and this low number masks the real debt burden. Two countries that also had low debt burdens before banking crises were Spain and Ireland. They’ve both required bailouts, so Australian politicians and economists should not be complacent about their public debt levels.”

Tonight I get to have dinner with good friends Neil Howe and David Tice. It is always a fascinating conversation with these guys around. But for now, down under we go.

Your trying to catch up with his shadow analyst,

John Mauldin, Editor

Outside the Box

subscribers@mauldineconomics.com

Australia: Running Out of Luck Down Under

By Jonathan Tepper, Variant Perception

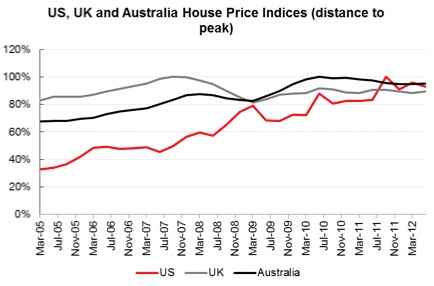

Australia has been described as the lucky country, but it is running out of luck and has a terrible combination of fundamental factors. In fact, Australia reminds us in many ways of the housing bubbles in the UK, Spain and Ireland. In each case, the country experienced a banking crisis.

Australian growth has been dependent on two huge bubbles: a domestic housing market that is one of the most overvalued in the world and a reliance on the Chinese fixed asset investment craze. Despite extraordinary commodity exports, Australia has run current account deficits and has a terrible international investment position. A substantially weaker currency in Australia is inevitable given fundamental factors. Oversized banks dependent on external financing, a bursting housing bubble and a slowing Chinese economy are all fundamental factors which are likely to weigh on the currency. As we explain, a weaker currency can either come in the form of the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) reducing interest rates or a balance of payment-like crisis in which foreigners pull funding from the banking sector. In both cases, the RBA would likely have to expand domestic liquidity substantially to prop up the banking system.

Please visit our website for the full version of the report.

> Australia is a classic case of the Dutch Disease. The Dutch Disease denotes the loss of competiveness in the tradable manufacturing and industrial sector as a result of a resource/commodity boom which leads to an overvalued real exchange rate. In Australia, the mining sector has crowded out almost all other sectors of the economy and also funnelled credit and liquidity into a housing bubble in the real estate sector.

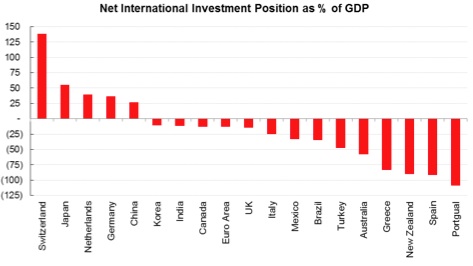

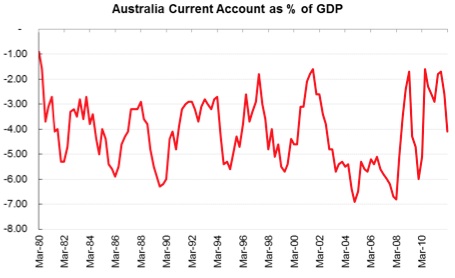

> Australia net external debt levels resemble those seen in the European periphery; the currency is fundamentally vulnerable. Australia has been running a persistent current account deficit since 1980 and the country’s negative net international investment position is one of the largest in the world. On this background, the strong currency makes no sense and fundamentally the currency is very vulnerable to capital flight from the banking system.

> Australian banks and corporates rely heavily on foreign funding; the RBA will have to provide liquidity through LTROs. Structural global deleveraging and stop-go flows add volatility for Australian banks. As the housing market continues to correct, it may be difficult for Australian banks to fund themselves. Lowering interest rates will hurt the margins of the banks, and the RBA will likely be forced into domestic liquidity operations to prop up its banks.

> Two options to weaken the currency, lower rates or a balance of a payments crisis. The Australian currency will weaken in one or two ways. Either the RBA gradually reduces interest rates to accommodate a structurally slowing economy and a relative end to the mining boom or the economy will suffer from a balance of payment crisis as external financing dries up due to the decline in the terms of trade exposing the negative current account.

> Australia’s commodity sector is tied to a structurally slowing Chinese economy. The commodity sector remains a force to be reckoned with in Australia and will remain cyclically tied to China. Still, the Chinese economy is structurally slowing down and this will impact the growth rate of mining and resource related activities in China. Australia is likely sitting on significant overcapacity in the mining sector which will be difficult to transfer to other sectors.

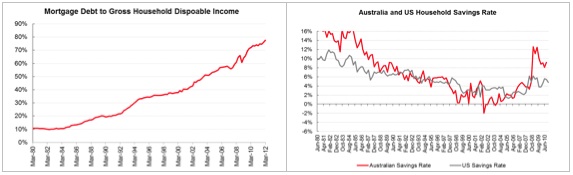

> The Australian consumer is overlevered, but demographics are relatively positive going forward. The correction in the Australian housing market is far from over and the Australian households remain overlevered. Yet, the savings rate has already increased substantially and in the long run demographics look far more robust than in eg Europe.

> Stay long government bonds in Australia on convergence towards low interest rates in the rest of the OECD. Whether it be as a result of the RBA gradually cutting rates to reflect slower growth or because foreigners start bidding up Australian bonds due to carry, yields are going down in Australia. We continue to like being long government bonds in Australia.

> Our long-term technical buy signal on Australian equities is in effect, but avoid miners and banks. We currently have a long term technical buy signal in effect on Australian equities as a result of the recent sharp sell-off. This is usually followed by good returns over the next 6 months or so. Although the market cap on the ASX 200 strongly favours overweight in mining and financials (market weight), we would avoid these two sectors and buy into defensives (consumer staples and health care) as well as industrials.

> Industrials and manufacturing will outperform on lower interest rates and a weaker currency. The gradual end to Dutch Disease will eventually lead to outperformance of the industrial sector. In the long run, our view is that the Australian equity market cap will re-weight away from mining and financials towards industrials and eventually consumer and retail.

> Buy CDS on big four Australian banks. Australian banks remain the weakest link in Australia’s economy, and they are too big to fail. We like buying CDS on Australian large cap banks as an outright trade or as a hedge against the long-term technical buy signal on Australian equities mentioned above.

Unwind of Dutch Disease in Australia requires a significantly weaker currency

The Australian economy needs a substantially weaker currency to regain competitiveness outside the mining sector. As we detail below, this can happen either through the RBA reducing interest rates or through a balance of payment type crisis in which foreigners pull funding. In either case, the Australian dollar is set to weaken substantially.

Australia is likely to have built up significant overcapacity in mining relative to a global demand. In short, it is a bubble that is in the process of bursting.

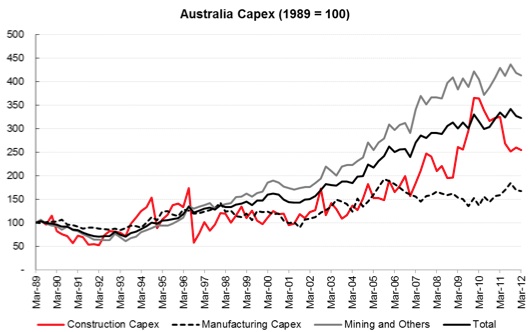

Economic growth in Australia has been largely driven by two booming sectors, mining and construction (housing and real estate). Since 1989, mining and construction capex have increased by a factor of 4 and 2.5 respectively. Both of these, however, are now no longer viable as growth engines.

Australia is a classic case of the Dutch Disease, which is the process by which a resource boom leads to an appreciation in the currency that stifles the tradable sector (manufacturing). Classic cases of Dutch Disease are associated with excessive wage growth in the non-tradables sector leading to an appreciation in the real exchange rate. The adverse macroeconomic effects include potential overconsumption relative to future income and significant mis-allocation of capital as the windfalls from commodity exports are channelled into non-tradables (eg real estate and construction) where the risk of asset bubbles is high.

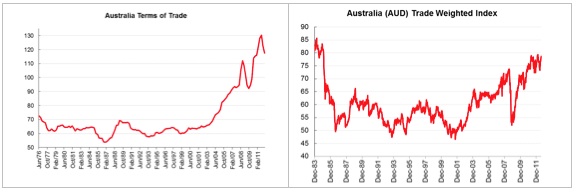

The Australian dollar is vastly overvalued on any fundamental metric. Australia’s terms of trade have soared and the currency is overvalued on most metrics. On The Economist’s famous Big Mac Index, the AUD is about 15% to 20% overvalued. Given the country’s persistent current account deficit and large external debt load the currency looks vulnerable based on macroeconomic fundamentals.

But the problem isn’t so much that Australia’s currency is currently overvalued based on fundamentals, but that the economy is likely to need an undervalued currency for an extended period in order to rise to the challenge of correcting the damage inflicted by the Dutch Disease.

It will be almost impossible to move mining capacity to other sectors in Australia. This is a textbook problem for economies who suffer from Dutch Disease. When the hangover arrives, writing off production capacity is often done at a considerable discount to cost. In addition, the manufacturing sector is under-developed and will not be able to take up the slack for the loss of momentum in construction and mining.

Australia’s external finances: It looks like the European periphery

The European periphery is an economic basket case. Australia resembles the European periphery in many important ways. The Australian banking system is highly reliant on external funding and will likely become dependent on the central bank for liquidity in the near future. Our view is that the RBA will have to become much more activist in supporting its major banks as the structural slowdown in China and the housing market continues.

We believe the RBA will ultimately be forced to take similar action to developed market central banks either by aggressively cutting interest rates or propping up banks through domestic open market operations akin to the liquidity injections seen by the ECB. Quantitative easing is also a possibility if the RBA is forced to buy bank debt to try to stave off a financial crisis. Under such a scenario, the AUD would fall considerably.

The crisis-stricken economies along the eurozone periphery share one key characteristic: their external debt is too high and their net international investment position (NIIP) – measuring the difference in stock value between assets held abroad and asset held domestically by foreigners – is deeply negative.

Yet, a closer look and you will find Australia and its neighbour New Zealand in the same company, with negative NIIPs well above countries such as Turkey and Brazil.

Source: IMF and National Statistical Sources

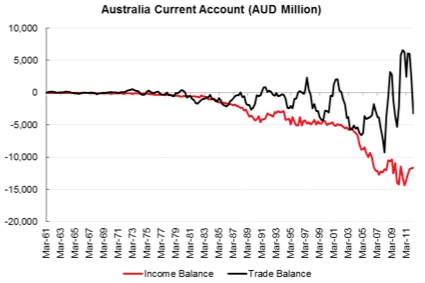

Australia’s current account has been negative since 1980, but the interesting thing is that it has remained negative even as the export mining boom has accelerated in the past decade. This is similar to South Africa, that has also run current account deficits for most of the last decade – despite having a sizable export sector – as consumers essentially borrow to spend.

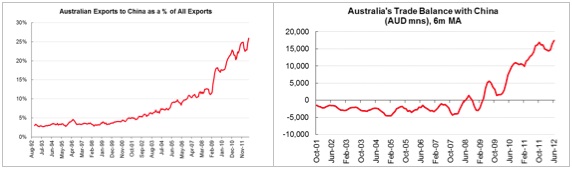

The remarkable fact is that while Australia’s trade balance with China has risen steadily to reflect the mining boom (see sections below), the overall trade balance has not been consistently positive (quite the opposite).

As Australia’s terms of trade starts to decline or even stops growing, the current account balance will become even more exposed due a now structurally negative income balance. This will add further fundamental pressure on the currency.

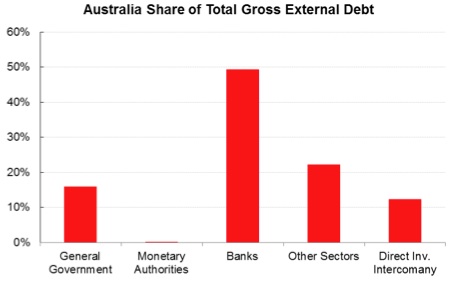

The majority of Australia’s external debt is held in the country’s banking sector with banks’ gross external debt standing at around 45% of GDP in 2012.

Source: IMF

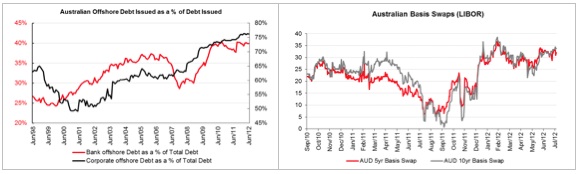

Both Australian banks and Australian corporates are highly dependent on international funding for their financing operations with funding costs proxied by the basis swap (essentially what an Australian bank has to pay for USD funding).

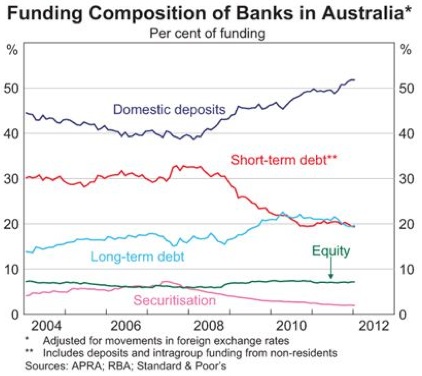

However, based on the latest data from the RBA, the funding profile has improved in the past two years with deposits now accounting for a larger share of the total funding profile. Furthermore, the maturity of external wholesale debt has been extended significantly.

Source: RBA Statistical Bulletin, March 2012

A total funding need from external sources at 40% of total funding is extraordinarily high. Moreover, about half of this external debt is short term. This increases risk yet further should Australia face a funding shock, driven either by events at home (a severely slowing economy), or abroad (eg a euro-driven credit event).

Cost of funding for Australian banks have gone up markedly since mid-2011 as competition for deposit funding has pushed up costs of term deposits. In addition, extending maturity on wholesale funding has also proven costly especially in relation to a heightened risk premium attached to bank credit in general, as well as the fact that many of the big Australian banks were recently downgraded by S&P.

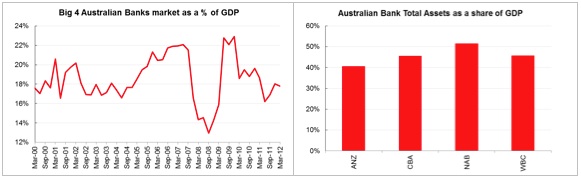

In the event of a funding crisis, it is unthinkable that Australian banks would be left to the whims of international funding markets. There are two reasons for this. Firstly, the Australian banking system is essentially an oligopoly with four main big players, each of them systemic on their own. Their combined market cap is just shy of a fifth of GDP and their total assets, in combination, equal an impressive 183% of GDP (based on annualised Q1-12 GDP figures). Secondly, Australia is not in the same boat as the European periphery. It is much more like the UK in 2007. The RBA has full control of its balance sheet (and currency) and has all the tools it needs to inject liquidity into banking system through LTRO-type operations.

Moreover, if there was any sudden fall in dollar funding for Australian banks it is likely the Fed would step in with dollar swap lines, as it has done with the BoE and the ECB.

Ultimately, our view is that the Australian economy is very similar to the UK economy in several respects (overvalued property market, excessive household debt, etc). In part, as a result of the mining boom and as a result of low global interest rates in the past decade, Australia has also had a severe housing bubble. This bubble is now in the process of deflating.

There is considerable deleveraging ahead for the Australian consumer with household debt still at significant levels. Australian consumers remain overlevered with especially mortgage debt as a percentage of income still high, but the savings rate has also increased and looks to be sitting at a permanently higher level than seen at any point since 1990.

The RBA has openly stated that it is not worried about a slowdown in the Australian housing market, but as the slowdown grinds on it will be difficult for them not to take notice. A final note from GMO, the investment management firm. They did a study on bubbles and identified – using their definition for what a bubble is – 34 bubbles over the years. 32 of these are back to the trend from before the bubble began. The only two outstanding are the UK housing market and the Australian housing market.

Australia is levered to a slowing Chinese economy

Australia will continue to be cyclically tied to China, but structurally the economy is likely to suffer from substantial overcapacity relative to a slowing Chinese economy. China’s structural growth rate is likely to fall significantly in the coming years and investment growth will wane. This is bearish for the Australian mining sector.

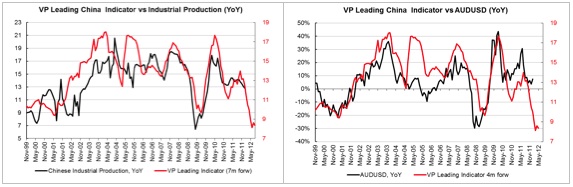

The best way to show the connection between growth in Australia and China is to overlay our leading indicator for industrial production in China with annual changes in the AUDUSD.

The strong correspondence between the charts clearly shows that the currency has been tightly correlated to the cycle in China in the last decade. The chart to the right shows a very high correlation between the Chinese and Australian business cycle.

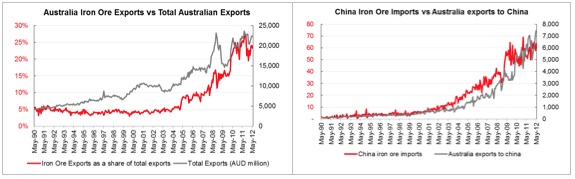

The Australian trade balance with China has continued reaching new highs in the first half of 2012, and while the Chinese economy may certainly rebound in relative terms, Australia’s strong dependence on China will turn into a disadvantage as the Chinese economy slows down.

There is no doubt that China may have had its best years in terms of headline GDP growth, but it is unlikely in our view that the economy will wither away as an important component of the global business cycle.

Cyclically, Australia will continue to benefit from expansions in China, but structurally, Australia will suffer as the trend growth of the Chinese economy slows down.

For Australia, the main problem lies in the structural slowdown that we are likely to see in China. Chinese GDP growth increased from about 6-7 % to a peak of 14% before the crisis. Growth rebounded to above 10% in the first half of 2010, but the country has not been able to sustain this rate.

Implications for asset prices – Rates and currency to go lower, banks and miners to underperform

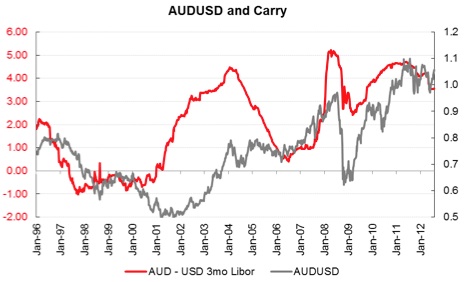

The Australian currency has continued to defy the vulnerabilities of the economy and instead responded to the search by international investors for carry and yield. In a world where developed market interest rates are zero or even negative, the Australian dollar has become an attractive, and indeed one of the only, sources of yield.

A weaker currency is necessary for the unwind of Australian Dutch Disease and in our view, there are two avenues through which this can occur.

1. Economic headwinds in the form of a slowing Chinese economy and a continuing slump in the domestic housing market will force the RBA to reduce interest rates further. Given the impact this would have on domestic banks’ interest rate margins, the RBA would likely have to aid banks with liquidity and funding through LTRO-like operations akin to the ones seen at the ECB.

2. A classic balance-of-payments type crisis in which a continuing decline in the terms of trade exposes the vulnerability of the external position. The current account would widen, and Australian banks would find it difficult to secure international wholesale funding. In such a situation, the RBA could choose to invert the domestic yield curve to attract funding for the current account (essentially protecting the currency), but this is very unlikely in our view. Australia would in such a case benefit from a weaker currency and the path of least resistance would be for the RBA to support the banks directly through LTROs and thus replace the source of external funding.

The critical issue in the scenarios above is whether policymakers actively seek to weaken the currency before the market does. Given the current tone set by the RBA, option two seems most likely, but rates have already come down and the RBA is likely to continue to lower interest rates if the economy weakens further.

A caveat is that in any crisis-like situation, given the central role of the domestic banks and their reliance on external funding, interbank rates would likely rise much higher. In this case, buying bank bill futures would be inappropriate to profit from lower base rates as the analogue of the LIBOR-OIS spread fro Australia would widen significantly, as we saw in the US, UK, etc in the wake of the Lehman bankruptcy. However, as bank bill futures in Australia are physically delivered, as opposed to cash settled, spreads may not widen to such extreme levels.

On bonds, we have advised investors to go long Australian bonds as we called for the RBA to cut rates. Now we can add an additional impetus in the form of the continuing strong bid by foreigners.

The search for yield and essentially diversification out of sovereign debt markets in distress has led to a surge in the foreign holdings of Australian government bonds. According to the latest data from the Australian Office of Financial Management, the total foreign ownership of Australian government bonds now stands at 80% of the total outstanding debt, up from 60% in 2006.

Source: Australian Office of Financial Management

Although this may sound high, government debt to GDP in Australia is low, at 30% (although is up from 16% in 2008). This low ratio is a result of running a budget surplus for most of the last 15 years. But, even though the situation looks good optically, the fact of the matter is Australia would have to backstop its banks in the event of a crisis, and this low number masks the real debt burden. Two countries that also had low debt burdens before banking crises were Spain and Ireland. They’ve both required bailouts, so Australian politicians and economists should not be complacent about their public debt levels.

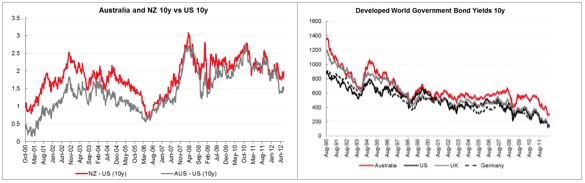

We remain of the view that rates in Australia will converge to the lower bound currently set by the rest of major central banks. This process has been progressing for the last 6m-12m and in our view it will continue.

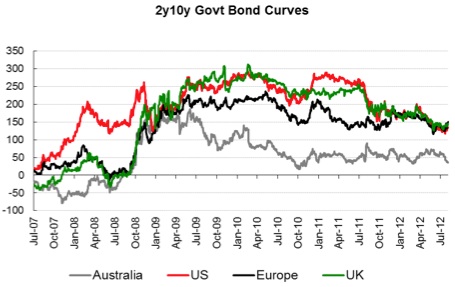

The Australian yield curve is considerably flatter than in the rest of the developed world. We think this will also reverse as short-term interest rates come down on the back of foreign buying and a dovish RBA.

The Australian dollar will not continue to defy fundamentals even if foreign central bank diversification means that the currency continues to see bids driven by structural as well as cyclical forces. We believe that the recent compression in the yield differential will weaken the AUD.

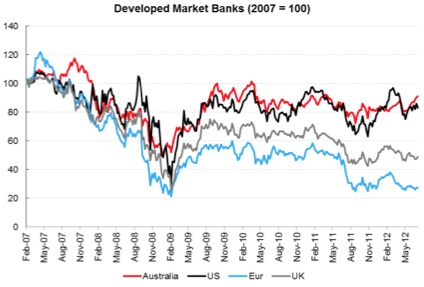

Australian banks will suffer. Indeed, Australian banks have recently outperformed their developed world peers but this is not sustainable given their vulnerability to external funding conditions and a slowing domestic market, putting a pressure on earnings.

Relative to their base value in 2007 we believe that Australian banks should trade much closer to their UK rather than their US counterparts. We like buying CDS on Australia’s big four banks both as an outright trade, but also as a hedge against a long index exposure (on the basis of a long-term technical buy signal – see full report for details).

© Copyright 2012 by Variant Perception® LLC

What's been said:

Discussions found on the web: