July 2012

Macro Factors and Their Impact on Monetary Policy,

The Economy and Financial Markets

Summary

The global economy is likely to continue to slow for the balance of 2012. The Euro Zone is in a recession that is intensifying, as previously strong countries are now slowing and the weak become weaker. In recent weeks short term yields have dropped below zero percent in five countries. This is clearly a sign that liquidity is deteriorating and confidence is eroding. Investors in weak countries are moving their savings to the healthier countries, trying to find the high ground and avoid being swept away. Being willing to accept a negative return on their savings, these investors are guaranteeing a loss, but view safety as more important. Truly extraordinary times we are witnessing. The gradual slowing we expected in the U.S. is likely to weigh on GDP growth and on corporate revenue growth in the third and fourth quarters. More than half of the companies which have reported second quarter results have noted a decline in sales. The road isn’t going to get any easier in the second half of this year. China’s economy is slowing more than policy makers expected, which is why the Peoples Bank of China has cut rates twice since early June. These reductions, and anticipated additional cuts, are more likely to stabilize growth, rather than result in an acceleration of growth. Brazil and a host of Asian countries that have fed China’s insatiable demand for raw materials in recent years will continue to struggle with the 30% downshift in demand from China. The global economy is entering a dangerous phase of slowing growth and few policy options to reverse the ongoing economic contraction.

The Federal Reserve and the Placebo Effect

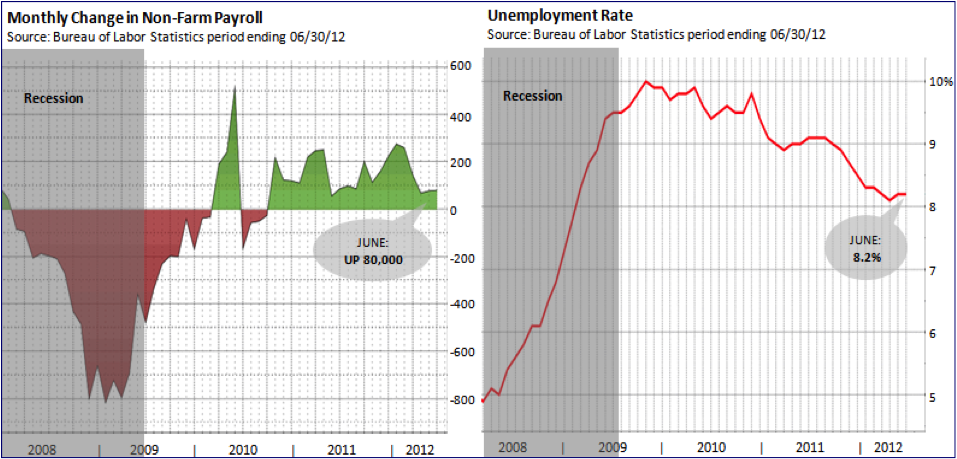

According to the official arbiter of the economy, the recession ended in June 2009. Despite three years of ‘recovery’, the unemployment rate is 8.2%, and has been above 8.0% for 41 consecutive months. In the previous 60 years, it exceeded 8.0% a total of 39 months. The more inclusive under employment rate is 14.9%. The average length of unemployment is 39.9 weeks, or more than three years. Average weekly earnings are up just 2.2% over the last year, which means most people are not keeping up, since the cost of living has increased by more than 2.2%. It shouldn’t come as a surprise that retail sales have fallen the last three months. Core retail sales, which exclude building materials, cars and gasoline purchases, have declined in two of the last three months. Manufacturing and exports were areas of strength in 2011, but are now softening. According to the Institute of Supply Management, manufacturing activity, new orders and new export orders all declined in June.

As the evidence of a slowdown in the U.S. economy has accumulated in recent weeks, strategists and commentators have lamented that the reports weren’t even more negative, since more weakness would spur the Federal Reserve to launch QE3. We expected the economy to slow as we approached mid-year, and continue to believe the economy will prove weak enough to force the Fed’s hand. However, as we have noted previously, the Federal Reserve’s Ace in the Hole is QE3. They aren’t going to play that card, or even discuss it, until it’s needed. This is why Chairman Bernanke did not tip his hand when he presented the Federal Reserve’s Semiannual Monetary Policy report to Congress on July 18. Some strategists have suggested the Federal Reserve will announce QE3 at their next meeting on August 1, since waiting until subsequent meetings on September 13 or October 23 would be too close to the election. Others are sure the Fed will make the announcement at the Kansas City Federal Reserve’s annual Jackson Hole confab in late August, as the Fed did in 2010. The Macro Strategy Team continues to believe that given everything the Federal Reserve has done since 2008 to stabilize the financial system and foster a self sustaining recovery, they are not likely to allow the November election to prevent them from acting if needed. As a result, they will launch QE3 only when economic conditions in the U.S. or events in Europe dictate. There is simply too much at stake to allow politics to guide this decision. While many investors wait with bated breath for QE3, they have overlooked recent negative economic reports since they believe the stock market will rally once the Fed moves on QE3. This is keeping selling pressure low, and helping the stock market hold up. The Federal Reserve is thus already getting mileage from the expectation of QE3.

We fully expect equity markets to rally when the Federal Reserve announces QE3. However, the obsession with QE3 is misguided since the two prior Quantitative Easing programs failed to ignite a self sustaining recovery, and another round is not likely to succeed either for numerous macro reasons. Once investors realize that QE is no magic bullet, equity markets could be especially vulnerable. The more important observation and understanding is that monetary and fiscal policy has been conducted based on a misguided principle for at least three decades.

Economics has often been called the dismal science and for good reason. Unfortunately, that hasn’t dissuaded politicians and central bankers from embracing economic theories that result in more negative unintended consequences than benefits. Prior to 1979, the Federal Reserve had one policy mandate, which was to conduct monetary policy so prices would be stable. The runaway inflation of the 1970’s is testimony to how well the Federal Reserve performed in pursuit of that mandate. Congress was so impressed by the Fed’s sterling performance that it gave it a second mandate with the passage of the Full Employment and Balanced Growth Act, which was signed into law by President Jimmy Carter on October 27, 1978. Never mind that there have been extended periods when full employment contributed significantly to inflation. For Congress, the notion of policies which are contradictory is almost perfection, since half the voters will be satisfied and the other half ripe for campaign contributions to ‘fix’ the problem.

These policy mandates were based on the belief that the business cycle could be tamed if monetary policy was fine tuned and fiscal policy used to offset weaker demand during economic slowdowns. The business cycle has been in existence as long as there has been something to sell and willing buyers. The notion the business cycle could be suppressed with the ministrations of monetary and fiscal policy should have been deemed preposterous. Instead, hubris trumped the obvious. There is a natural ebb and flow for everything on this planet, from the tides to the seasons of the year. Recessions are a natural part of the business cycle, just as night follows day. In a practical sense, recessions cleanse the economy and financial system of excesses, whether it is unneeded inventories or pushing overleveraged businesses out of business. In this way, a balance is maintained between the supply and demand of raw materials, labor, and credit, which ensures the underpinnings of an economy remain sound.

By 2007 it appeared that manipulating monetary and fiscal policy together had become the elixir, if not in eliminating the business cycle, at least in taming it. In the 300 months between 1983 and 2007, there were only 16 months the economy was in recession. In the 300 months from 1957 through 1982, there were 64 months of recession. The recessions in this 25 year period were also deeper on average than the two eight month shallow recessions in 1991 and 2001. On the surface, it looked like policy makers had become Masters of the Universe, with Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan orchestrating every movement of an economic symphony. Unfortunately, the appearance of success only masked a number of consequential unintended consequences.

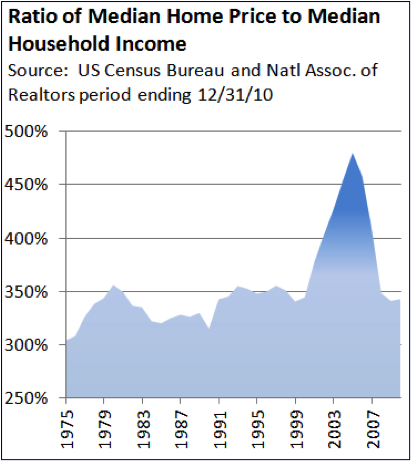

In 2004, investment banks petitioned the SEC to increase their leverage from 12 to 30 times capital. The volatility of the business cycle had been far lower for a long time, so assuming more leverage seemed reasonable. Their request was granted and banks proceeded to leverage their balance sheets on the safest investment of all – home values. After all, since the depression, home prices had never declined. This track record was established because bankers religiously limited a prospective home buyer’s mortgage payment to one-third of their income. Maintaining this ratio is why median home prices held steady around 3.3 times median income between 1965 and 2000. The increase in home prices between 1965 and 2000 was supported by a commensurate increase in incomes. From 2000 to 2006, the ratio of median home values soared from 3.3 times median income to 4.6 times median income. This was made possible by a significant lowering of lending standards. Amazingly, even though bankers were a central cog in the mortgage lending machine, they continued to leverage their balance sheets on home values. They weren’t blinded by the light, but by the green. And while this played out, regulators, the Federal Reserve, and Congress did nothing. When the goal is to tame the business cycle, nothing is off the table.

In 2004, investment banks petitioned the SEC to increase their leverage from 12 to 30 times capital. The volatility of the business cycle had been far lower for a long time, so assuming more leverage seemed reasonable. Their request was granted and banks proceeded to leverage their balance sheets on the safest investment of all – home values. After all, since the depression, home prices had never declined. This track record was established because bankers religiously limited a prospective home buyer’s mortgage payment to one-third of their income. Maintaining this ratio is why median home prices held steady around 3.3 times median income between 1965 and 2000. The increase in home prices between 1965 and 2000 was supported by a commensurate increase in incomes. From 2000 to 2006, the ratio of median home values soared from 3.3 times median income to 4.6 times median income. This was made possible by a significant lowering of lending standards. Amazingly, even though bankers were a central cog in the mortgage lending machine, they continued to leverage their balance sheets on home values. They weren’t blinded by the light, but by the green. And while this played out, regulators, the Federal Reserve, and Congress did nothing. When the goal is to tame the business cycle, nothing is off the table.

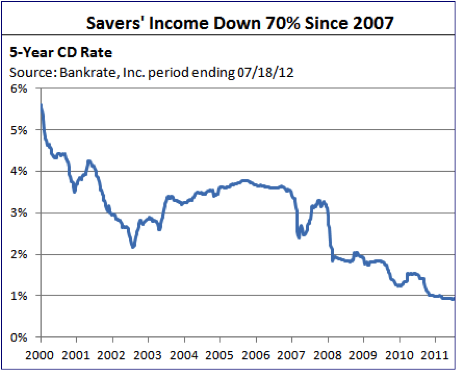

In late 2008, the mismanagement of too-big-to-fail banks forced the Federal Reserve to slash interest rates to near 0%, where they have held ever since. This has had an unduly negative impact on savers, who have seen their interest income fall by more than 70% over the last five years. It has hurt older Americans especially hard. The silent majority, who played the game the right way, by working hard, saving their money, and not living beyond their means. And the only thing that has changed is that the too-big-to-fail banks in 2008 are even bigger.

In late 2008, the mismanagement of too-big-to-fail banks forced the Federal Reserve to slash interest rates to near 0%, where they have held ever since. This has had an unduly negative impact on savers, who have seen their interest income fall by more than 70% over the last five years. It has hurt older Americans especially hard. The silent majority, who played the game the right way, by working hard, saving their money, and not living beyond their means. And the only thing that has changed is that the too-big-to-fail banks in 2008 are even bigger.

The Federal Reserve’s effort to keep short and long term Treasury rates low represents a ticking time bomb for state pension funds. Most state public pension plans are budgeting, over the next 30 years, to average 7.5% to 8.5% annually on their investment portfolio. In contrast, corporate plans use an average of 4% to 5%. Obviously, the assumed average annual rate of return (AAR) is critical in determining that assets will be available to meet future pension obligations for plan retirees. If the plan earns less than the assumed AAR, the state won’t have money to pay for 100% of the promised benefits. The assumed AAR also determines how much money a state must contribute from the current year’s budget. If the assumed AAR was lowered from 7.5% to 7.0%, the state would need to increase this years and all subsequent years annual contribution. The increase in the annual contribution will cover the .5% shortfall in the investment return over the next 30 years.

Given the fiscal pressure on many state budgets, lawmakers in those states are loathed to lower the assumed AAR for their state. According to a study by Stanford University last year, California would have to increase its annual pension fund contribution by more than $7 billion per year, if lawmakers lowered the AAR from 7.5% to 6.2%. The Center for Retirement Research at Boston College analyzed the health of 126 pension plans based on 2010 statistics. It found that in aggregate those 126 plans were only 76% funded. A recent report by the Pew Center on the States suggests state pensions are underfunded by $757 billion, similar to states own figures. However, the numbers do not include the potential costs of retirement healthcare.

On July 18, the State Budget Task Force identified six major threats to states’ fiscal health. They are Medicaid spending, under-funded retirement promises, budgetary ‘gimmicks’, ignored infrastructure, volatile tax revenues, and expected federal budget funding cutbacks to states. The Task Force was Co-Chaired by former Chairman of the Federal Reserve Paul Volcker and former Lieutenant Governor of New York Richard Ravitch. On June 26, the Governmental Accounting Standards Board approved new rules that will force state governments to record pension costs sooner, disclose shortfalls more prominently, and calculate retirement benefits using more conservative assumptions. The Center for Retirement Research at Boston College found that after incorporating these new guidelines the funding level for the 126 plans they analyzed would fall from 76% to 57%, and increase the level of underfunding to near $1 trillion.

With the 10-year Treasury yield near 1.5%, and the yield on the 30-year Treasury bond hovering near 2.6%, it is reasonable to wonder how states will meet their retirement and health care obligations in coming decades. It is also reasonable to ask where the money will come from if investment returns fail to measure up.

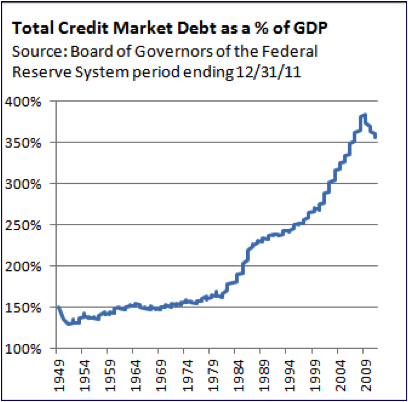

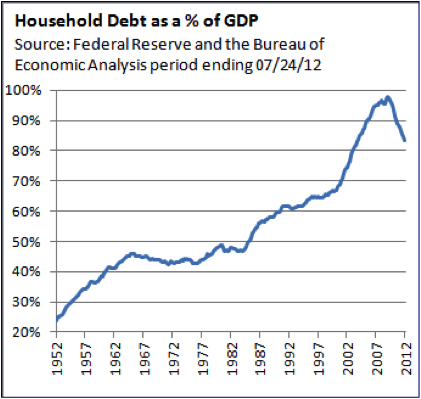

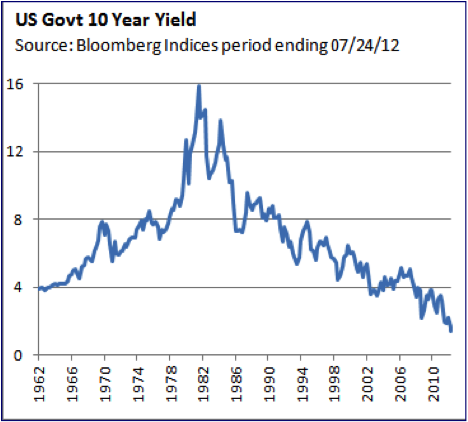

The biggest unintended consequence is how leveraged our economy has become since 1979. Tasked with its new mandate of full employment, the Federal Reserve subsequently oversaw the largest increase of debt in our nation’s history. For each $1 of GDP in 1979, there was $1.60 of debt. By 2007, there was $3.70 of debt for every $1.00 of GDP. During the 30 years between 1979 and 2007, debt grew almost 4% faster than GDP every year. This build up was facilitated by a significant decline in interest rates from their peak in 1981. As borrowing costs fell, consumers found they could assume more debt for buying cars, homes, and other goods and services, without their monthly payments going up much. Between 1982 and 2007, Household Debt as a percent of GDP more than doubled, rising to 98% of GDP from 44% in 1982. The consumer borrowing splurge was topped off as home owners converted home equity into an ATM machine, just prior to a 30% plunge in home values. During this 25 year window, consumer debt grew more than 3% faster annually than GDP.

The biggest unintended consequence is how leveraged our economy has become since 1979. Tasked with its new mandate of full employment, the Federal Reserve subsequently oversaw the largest increase of debt in our nation’s history. For each $1 of GDP in 1979, there was $1.60 of debt. By 2007, there was $3.70 of debt for every $1.00 of GDP. During the 30 years between 1979 and 2007, debt grew almost 4% faster than GDP every year. This build up was facilitated by a significant decline in interest rates from their peak in 1981. As borrowing costs fell, consumers found they could assume more debt for buying cars, homes, and other goods and services, without their monthly payments going up much. Between 1982 and 2007, Household Debt as a percent of GDP more than doubled, rising to 98% of GDP from 44% in 1982. The consumer borrowing splurge was topped off as home owners converted home equity into an ATM machine, just prior to a 30% plunge in home values. During this 25 year window, consumer debt grew more than 3% faster annually than GDP.

There are two key conclusions that can be made from these statistics. The first is that debt financed demand elevated GDP above its natural growth rate for most of this 25 year period, and especially after 2001. This was great while it lasted and made it easier for politicians to get reelected and praise for the Maestro running the Federal Reserve. If debt were steroids, the economy hit an economic home run as often as Barry Bonds and as far as Mark McGuire. But like all things, its time has passed. The second conclusion is more important for understanding why this ‘recovery’ has been so feeble, and why the economy is likely to grow below its natural growth rate in coming years, maybe for another decade. This is not the first time in history that a debt bubble has formed and then begun to deflate. Historically, once a debt bubble pops, assets that were beneficiaries of debt financed demand, decline causing a chain reaction that has taken up to 20 years to unfold.

There are two key conclusions that can be made from these statistics. The first is that debt financed demand elevated GDP above its natural growth rate for most of this 25 year period, and especially after 2001. This was great while it lasted and made it easier for politicians to get reelected and praise for the Maestro running the Federal Reserve. If debt were steroids, the economy hit an economic home run as often as Barry Bonds and as far as Mark McGuire. But like all things, its time has passed. The second conclusion is more important for understanding why this ‘recovery’ has been so feeble, and why the economy is likely to grow below its natural growth rate in coming years, maybe for another decade. This is not the first time in history that a debt bubble has formed and then begun to deflate. Historically, once a debt bubble pops, assets that were beneficiaries of debt financed demand, decline causing a chain reaction that has taken up to 20 years to unfold.  Banks are forced to curtail lending, and over indebted consumers are forced to save more and spend less, since they can no longer finance their lifestyle through borrowing. The net result is that aggregate demand declines, and remains below average, while consumers pay down debt and banks rebuild their balance sheets. While this process plays out, Congress, as they have during every other economic slowdown, has ramped up spending to offset the lower level of aggregate demand. The result has been trillion dollar deficits that are unsustainable. The Federal Reserve has held rates near 0% for almost four years, to spur borrowing and demand, just as they have in the past. Only this time the elixir has lost its power. Policy makers set the course long ago, and the only modifications have been the size of budget deficits since 2008 and the level of monetary accommodation. Given these inputs, the strength of the current recovery is extraordinarily paltry. And if the past is any guide, GDP growth is not likely to exceed 2% on average in coming years. If this conclusion is correct, stock market P/E ratios have plenty of room to fall from the current ‘cheap’ valuation.

Banks are forced to curtail lending, and over indebted consumers are forced to save more and spend less, since they can no longer finance their lifestyle through borrowing. The net result is that aggregate demand declines, and remains below average, while consumers pay down debt and banks rebuild their balance sheets. While this process plays out, Congress, as they have during every other economic slowdown, has ramped up spending to offset the lower level of aggregate demand. The result has been trillion dollar deficits that are unsustainable. The Federal Reserve has held rates near 0% for almost four years, to spur borrowing and demand, just as they have in the past. Only this time the elixir has lost its power. Policy makers set the course long ago, and the only modifications have been the size of budget deficits since 2008 and the level of monetary accommodation. Given these inputs, the strength of the current recovery is extraordinarily paltry. And if the past is any guide, GDP growth is not likely to exceed 2% on average in coming years. If this conclusion is correct, stock market P/E ratios have plenty of room to fall from the current ‘cheap’ valuation.

The movie “The High and the Mighty” was released in 1954 and depicted an airline flight from Honolulu to San Francisco that develops engine problems. Once past the point of no return, they can’t turn back, and must try to make it to San Francisco hoping they have enough fuel. Obviously, we are past the point of no return in terms of fiscal and monetary policy. However, that reality won’t stop Congress and the Federal Reserve from trying, hoping the economy will remain aloft. The Placebo Effect occurs when a fake treatment is given, but the patient’s condition improves because the patient has the expectation the ‘treatment’ will heal them. The substantive discussion our country should be engaged in is not when the Federal Reserve will launch QE3 or whether Congress should cut spending or raise taxes. The real debate should be whether manipulating fiscal and monetary policy should be undertaken at any time, since the business cycle cannot be defeated and serves as the most important market force in an economy. If this debate ever does occur, it won’t be until after the impact of QE3 has worn off, and investors realize that Quantitative Easing was just a Placebo.

Europe

If hubris played a role in U.S. policy makers believing the business cycle could be nullified with fiscal and monetary finesse, it certainly played a role in the formation of the European Union. The economic stress unleashed by the financial crisis in 2008 has proven that one size does not fit everyone, especially for an economic union so diverse and bound by a common currency. One of the primary fissures is the productivity gap between the northern members of the union, particularly Germany, and the southern countries Greece and Italy, which have extremely inflexible labor laws. Since they share the same currency, they must close the productivity gap through labor reforms. While reform is likely, it will take time and not be painless. Unfortunately, neither country has much time.

U.S. banks increased their balance sheet leverage to 20 to 1 from 12 to 1 starting in 2004, after receiving approval from the SEC. Not to be outdone, European banks expanded the balance sheet leverage to 40 to 1. U.S banks leveraged their balance sheets on home values, since home values hadn’t fallen since the Depression. European banks did them one better. They leveraged themselves with sovereign debt, which had the added benefit of not requiring reserves to be set aside, since no one expected sovereign debt to lose value and certainly not default.

U.S. banks increased their balance sheet leverage to 20 to 1 from 12 to 1 starting in 2004, after receiving approval from the SEC. Not to be outdone, European banks expanded the balance sheet leverage to 40 to 1. U.S banks leveraged their balance sheets on home values, since home values hadn’t fallen since the Depression. European banks did them one better. They leveraged themselves with sovereign debt, which had the added benefit of not requiring reserves to be set aside, since no one expected sovereign debt to lose value and certainly not default.

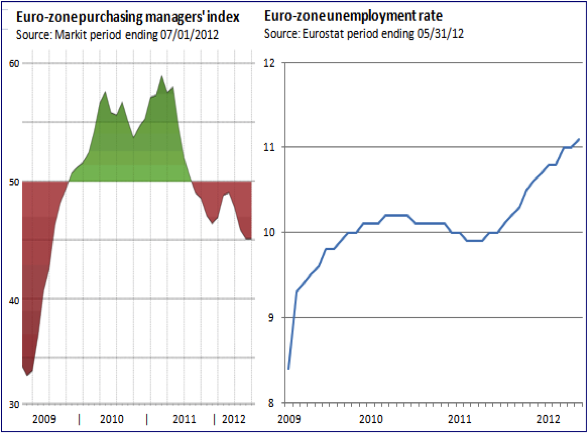

As we have discussed in recent months, one of the biggest headwinds that will weigh on Europe is the ongoing contraction in lending. This is particularly problematic since 80% of all credit extended to E.U. companies and consumers, comes from European banks. The lack of lending is sure to hit small and medium size firms especially hard as they have no access to capital markets. No doubt other international banks will move in and take advantage of the opportunity, but it won’t be nearly enough to overcome the lending shortfall. Corporate bankruptcies will increase as will unemployment. Tax receipts will remain weak, making it more difficult for Greece, Spain, Portugal, and eventually Italy and France to reduce their budget deficits. Rising interest rates will further burden budgets, making the task more difficult. There is a vicious vortex at work.

Banks in northern Europe have curtailed their lending to banks in southern Europe, particularly Spain. Since Spanish banks are unable to borrow in the capital markets or from other banks to fund their daily operations, they are accessing liquidity from the ECB. At the end of June, the bank of Spain said Spanish banks had borrowed $446.7 billion from the European Central Bank, which was an increase of $62 billion from April. However, more than $400 billion of the money received from the ECB has been returned to the ECB where it is held. Almost none of the money borrowed from the ECB by Spanish banks is finding its way into Spain’s local economy.

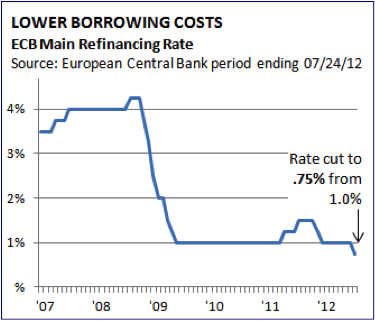

European policymakers are confronting the same limitations as their counterparts in the U.S. The ECB recently lowered its benchmark rate from 1.0% to .75%. The ECB will likely cut it more, but another notch or two down is not going to materially improve the economic outcome in Europe. The wiggle room from fiscal policy is even more limited. For Greece, Ireland, Portugal and Spain, fiscal austerity has meant weaker growth or a deepening recession. In the last two years, twelve of the seventeen countries in the E.U. have tossed out an existing government. U.S. politicians are naturally relieved to push the tough decisions, the decisions that call for leadership and courage, until after the November election.

European policymakers are confronting the same limitations as their counterparts in the U.S. The ECB recently lowered its benchmark rate from 1.0% to .75%. The ECB will likely cut it more, but another notch or two down is not going to materially improve the economic outcome in Europe. The wiggle room from fiscal policy is even more limited. For Greece, Ireland, Portugal and Spain, fiscal austerity has meant weaker growth or a deepening recession. In the last two years, twelve of the seventeen countries in the E.U. have tossed out an existing government. U.S. politicians are naturally relieved to push the tough decisions, the decisions that call for leadership and courage, until after the November election.

Europe’s financial crisis appears to be escalating and every summit (20 to date) has produced a solution whose half life is shorter. Short term yields have dropped below 0% in five countries, as money flees Greece, Spain, Portugal and possibly Italy. The willingness of investors to accept a negative return, guaranteeing a loss, is a reflection of fear. The recession in Europe is intensifying, which means it will adversely impact the global economy for longer than most investors expect.

China, India, Brazil

The U.S., Europe, Japan and Great Britain represent close to 65% of global GDP. China, India, and Brazil all have bright futures, and won’t be capsized by the extended period of weak growth that is taking hold in developed countries. But they will be buffeted since they do not have a middle class of sufficient size to absorb the excess capacity created by lower demand from developed countries, as well as country specific issues.

In the second quarter, China’s GDP slipped to 7.6%, the lowest since early 2009. Europe is China’s largest export market, representing 17% of China’s exports. In June, exports to Italy were off by 24%, France down by 5%, and lower by 4% with Germany. The surge in lending in 2009 and 2010 increased export production capacity. With demand from Europe contracting, and weakening from the U.S., China’s second largest export market, excess capacity is going to translate into bad loans that will become a problem in 2013 and 2014. The Peoples Bank of China will cut rates further in coming months. Although lower rates may cushion China somewhat from the global slowdown, it will not be enough to reaccelerate growth to historical norms.

In the second quarter, China’s GDP slipped to 7.6%, the lowest since early 2009. Europe is China’s largest export market, representing 17% of China’s exports. In June, exports to Italy were off by 24%, France down by 5%, and lower by 4% with Germany. The surge in lending in 2009 and 2010 increased export production capacity. With demand from Europe contracting, and weakening from the U.S., China’s second largest export market, excess capacity is going to translate into bad loans that will become a problem in 2013 and 2014. The Peoples Bank of China will cut rates further in coming months. Although lower rates may cushion China somewhat from the global slowdown, it will not be enough to reaccelerate growth to historical norms.

India is not only dealing with the global and a domestic slowdown, but also a domestic energy crisis. Shortages of coal, oil, and natural gas will require increasing imports of high cost fossil fuels. This is likely to push inflation higher and impact India’s budget deficit, as it subsidizes costs for the poor. India is being pushed to provide electricity to 400 million rural residents, almost one-third of its population. This is a structural problem that will dog India for years, and if not handled well, result in social repercussions that could be serious.

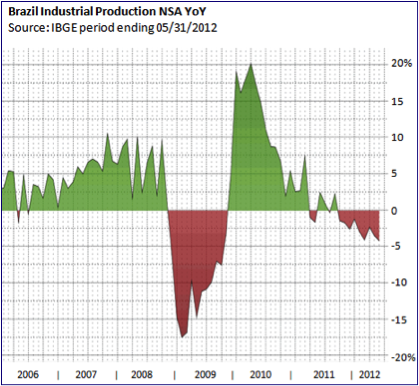

Since mid 2011, Brazil’s central bank has lowered its Selic rate from 12.25% to 8.0%. Despite the lower cost of money, GDP growth in 2012 is likely to slow to 1.8%. Brazil is dealing with a slowdown in exports and weaker domestic consumer demand. China is Brazil’s largest trading partner, and has cut back on its imports of iron ore and soy from Brazil. According to Capital Economics, debt payments represent 20% of household income. This is going to inhibit consumption for an extended time, and is why the response to lower interest rates has been so tepid. Many Brazilian consumers are simply tapped out.

Since mid 2011, Brazil’s central bank has lowered its Selic rate from 12.25% to 8.0%. Despite the lower cost of money, GDP growth in 2012 is likely to slow to 1.8%. Brazil is dealing with a slowdown in exports and weaker domestic consumer demand. China is Brazil’s largest trading partner, and has cut back on its imports of iron ore and soy from Brazil. According to Capital Economics, debt payments represent 20% of household income. This is going to inhibit consumption for an extended time, and is why the response to lower interest rates has been so tepid. Many Brazilian consumers are simply tapped out.

Macro Strategy Team

What's been said:

Discussions found on the web: