The Unemployment Surprise

By John Mauldin

October 8, 2012

You Know You Were Surprised

The Eat, Drink, and Get Sick Sector

The Really Important Employment Numbers

Portland, Chicago, Atlanta, and South America

The unemployment number surprisingly dropped to 7.8% last Friday, and the shoot-from-the-hip crowd came out in force. To say that the jobs report was met with skepticism would be a serious understatement. The response that got the most immediate airplay was ex-GE CEO Jack Welch (who knows a few things about making a number say what you want it to say) tweeting, “Unbelievable job numbers … these Chicago guys will do anything … can’t debate so change numbers.”

Not be left out, Fox Business quoted Ed Butowsky of Chapwood Capital Investment: “‘No way in the world these numbers are accurate,’ he said. ‘Somebody needs to do an investigation…. Investigate these numbers.'”

Such a significant drop in the unemployment rate does not seem, at least on the surface, to be consistent with the slowing economy. It certainly wasn’t what most Republicans were expecting one month prior to the elections, and the partisan reaction from my fellow Republicans was sadly predictable. So, since an investigation has been called for, this week we will do just that: we will investigate the numbers. What we will find is that the falling unemployment number was perfectly consistent with a slowing economy, if you look at the details. That seemingly contradictory conclusion gives rise to a question, gentle reader, that will take more than one paragraph to answer. It will make for some interesting reading, I think.

Let me start by acknowledging that one of the most dangerous things one can do in the writing business is try to separate a man from his pet conspiracy theories. But this is one conspiracy that needs to be thoroughly debunked, as the reaction to it is an example of the coarsening of our American culture. If some bit of data does not dovetail with our favorite meme, our immediate reaction is to shoot the messenger rather than examine the facts as presented. With that proviso, let’s jump right in.

You Know You Were Surprised

Like anybody else who is paying attention to the current economic situation, I was surprised when the headlines said that unemployment had dropped to 7.8%. A drop of that magnitude does not seem to be historically consistent with an economy growing less than 2%, with job growth – at least as measured by the Establishment Survey – barely keeping up with population growth, or with tax receipts that were relatively flat for the last month. My immediate reaction was “Show me the data.” There was clearly going to be something interesting lurking down among the details. And there was.

Before we wade into the data, though, I want to analyze the reaction. What if someone said, “The military is manipulating the data from Iraq and Afghanistan in order to help the election of the current administration,” (whether Republican or Democrat)? The appropriate response to such a statement would be to suggest that such a characterization was demeaning to the professionalism and integrity of our military professionals. I think it is doubtful that a statement like that would get much airplay or gain much credence in the public discourse. The military is a well-respected institution in the United States.

Yet we seemingly dismiss quite easily the professionalism of the employees of the Bureau of Labor Statistics when their data doesn’t fit our perceptions of reality. Let’s look at what they do. First and foremost, they collect data. In regards to employment data, they do two surveys. The first is the Establishment Survey, which polls 400,000 companies about the number of employees they have, whether they are full-time and part-time, and other details (along with income data). Then there is the Household Survey, which asks 60,000 households each month how many people live in the household and who is working, again distinguishing between full-time and part-time. If the job is part-time, they try to determine whether the part-time work is voluntary or whether it is for economic reasons, such as poor business conditions or because the person could only find part-time work. If a person does not have a job, they try to determine whether they have looked for a job within the past month or the past year.

The data they compile is surprisingly detailed. Want to know the unemployment rate in your city or metropolitan area? It’s likely to be found in the BLS data.

The problem with conspiracy theories is that there have to be people involved. In order to manipulate data within the BLS, you would have to get a surprisingly large number of people to cooperate. The fact is that many of these people have been with the BLS for many years and started working there during many different administrations, so presumably, they have different political affiliations, making it very unlikely that everyone would have cooperated in a conspiracy to cook the books this past month. Someone would have blown the whistle. It would be a career-ending move to try to manipulate the data, not to mention that I’m sure there are many laws against such manipulation.

The BLS process is rather straightforward. The data is collected and the numbers are crunched according to a very transparent formula. And then the results are published.

The Establishment Survey is what is known as contributory. By that we mean that this data feeds into other statistics we use in the government and business. It is considered to be accurate data. But note that it is constantly being revised as new and better data comes in. The monthly numbers we see first are the result of a survey, and that survey is as accurate as they can make it. But then actual data comes in the form of contact reports from state authorities and other sources, and the numbers are adjusted. Only a few of us data wonks pay much attention to the revisions.

The Household Survey is not, to my knowledge, contributory. The only major number we really get from it is the employment rate. As we will see in a few paragraphs, this survey is quite “noisy” from one month to the next, although over a period of about a year it conforms rather well to the Establishment Survey.

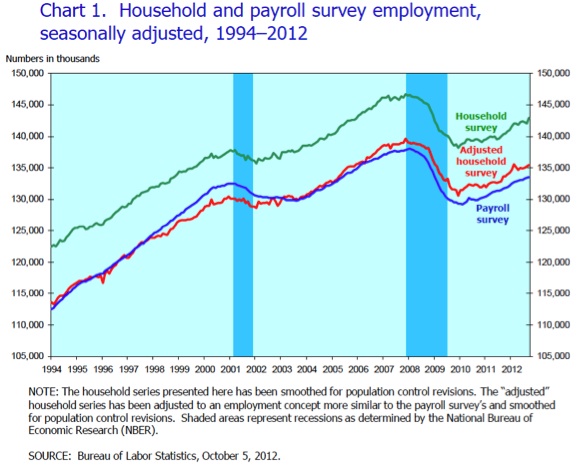

The following chart, courtesy of The Big Picture, shows a rather tight correlation between the two surveys. “Separately, and almost certainly unknown to Mr. Welch, the BLS issues a technical document every month that address the trends in both surveys. That document can be found here and contains the following chart:

“Among the objectives of the monthly analysis is to produce an Adjusted Household Survey (seen above). BLS:

“This [Adjusted Household Survey] is a research series created from household survey employment to be more similar in concept and definition to payroll survey employment. Household survey employment is adjusted by subtracting agriculture and related employment, nonagricultural self employed, unpaid family workers, private household workers, and workers absent without pay from their jobs, and then adding nonagricultural wage and salary multiple jobholders. The effects of population control revisions also have been smoothed out in the historical data in this series.

“But you knew that, right, Jack [Welch]? The Adjusted Household Survey shows that 1.836MM jobs have been created over the past 12 months. The Payroll Survey? 1.806MM. The difference between the two over the course of a year? A paltry 30,000. While there may occasionally be wide month-to-month swings (and the Household Survey is known to be the more volatile of the two), the two series generally track fairly closely over time, which is how data should generally be observed.” (The Big Picture)

In past letters, when commenting on the employment situation, I have noted that there are times when the Household Survey seriously underestimates the number of jobs, as compared to the Establishment Survey. This month the disparity is in the other direction. That is a function of the methodology of the survey. I’m sure that if BLS spent more money it could survey more households and get a more accurate picture, but I doubt it would be worth the money.

In summary, the fine people at the BLS do their best to collect the data is accurately as possible and make it available as quickly as possible. The formulas by which they interpret the data are well-known. To suggest otherwise demonstrates a lack of understanding of the process and essentially defames the people involved. If you don’t like what the data says, don’t shoot the messenger.

This is not a recent problem. In 2003-04 Democrats were constantly deriding the positive statistics coming out of the BLS. Dr. Austan Goolsbee, Obama’s ex-chief economic advisor, accused the government of “cooking the books” on the unemployment number in a New York Times article in late 2003 entitled “The Index of Missing Economic Indicators; The Unemployment Myth.” I actually agreed (and still do) with his analysis, just not his partisan rhetoric and conclusion, but that’s a story for another letter. (http://www.nytimes.com/2003/11/30/opinion/the-index-of-missing-economic-indicators-the-unemployment-myth.html – hat tip Bill King)

Now, with that out of the way, it is totally fair game to question the basis for the interpretation of the data. The way the government derives the unemployment numbers has changed significantly over the last 30 years. No surprise, then, that whatever administration is involved, the new equations for determining unemployment result in a lower unemployment rate than they would have if the 1980s methodology were still in place.

You are not counted as unemployed if you have not looked for a job for the last four weeks, by the current BLS methodology. That policy is very clear, and to my knowledge the policy was the same during the Bush administration.

I find that methodology rather bizarre. There are many people who have not looked for a job in the last four weeks; but if you asked, I bet just about every one of them would consider themselves unemployed. They would take a job if they could find one. That, to me, should be the definition of unemployed. And if you use the raw data, you can come up with that number on your own. Or you can create whatever definition of unemployment you want.

(There are literally hundreds of BLS data series. Want to know how Vietnam vets are doing? Hispanic women under 25? Married Asian males over 55? Unemployment just in your state or city? It’s there somewhere if you care to look. I am constantly amazed at the granularity of the data.)

John Williams of ShadowStats calculates his own unemployment and CPI numbers based on the older methodology (from the early ’80s); and, no surprise, it shows unemployment to be much higher than the government says. The Gallup organization would like us to measure the payroll-to-population ratio. If you’re not disabled and you’re receiving unemployment or welfare benefits I think you should be counted as unemployed.

Now we can come to the question of how we can have a drop in unemployment that is consistent with a very slowly growing economy. Bill King noted that employment taxes actually fell in September, then asked, how can 873,000 jobs have been generated, according to the Household Survey?

Median Real Disposable Income is up only 0.2% annually over the past few years, against the postwar average of 2.9%. The increase in average hourly earnings hasn’t kept pace with the rate of inflation, which means that workers are losing ground. Dr. Lacy Hunt estimates that about 1.5% of GDP growth in the first quarter was from manufacturing. Manufacturing jobs have been flat for the last two quarters.

For the last three years, while we were averaging between 120,000-160,000 new jobs a month that paid between $20,000-40,000, we were losing anywhere from 20,000-60,000 jobs a month that paid more than $70,000. A detailed study of job status earlier this year by the Center for Labor Market Studies at Northeastern University found that more than 53% of college graduates under 25 were underemployed last year – working in jobs unequal to their college or postgraduate attainment.

All of this is to say there is a reason why we don’t feel that unemployment dropped by 6% last month: we’re not seeing a brighter jobs outlook reflected in our paychecks.

The Eat, Drink, and Get Sick Sector

The Establishment Survey found only 114,000 new jobs. (Philippa Dunne of the Liscio Report noted wryly, “Our old friend the eat, drink, and get sick sector (bars and restaurants plus health care) accounted for 52% of total job gains.” There were significant revisions to the prior two months, but almost all of those jobs were in government (education-related) jobs. This bump in government jobs is part of a pattern and not a conspiracy of politicians to make things look better.

As noted above, the unemployment rate is taken from the volatile Household Survey. This month it shows 873,000 jobs created. 582,000 of those jobs were part-time for economic reasons. That means people wanted more work but could only get part-time jobs. 7.25% of all part-time jobs were created just last month!

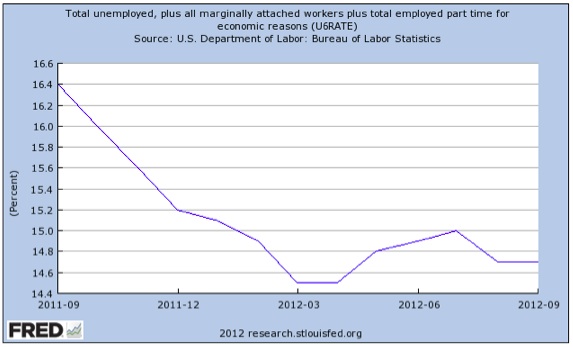

The BLS also gives us something called the U-6 unemployment rate, which is the total unemployed plus all marginally attached workers employed part-time for economic reasons. Right now the U6 unemployment rate is 14.7%, which is exactly where it was one month ago. The chart below is for the last year, and you can easily see that there’s been no change in the last month.

That means the entire drop in the headline unemployment rate is from the increase in part-time workers. That such significant numbers of people can only find part-time work is not a sign of a strong and growing economy. It is however completely consistent with a flat, lackluster economy.

If the next 0.3% drop in the unemployment rate is again due to a gain in the number of part-time workers, I don’t think anybody will be talking about how strong the US economy is.

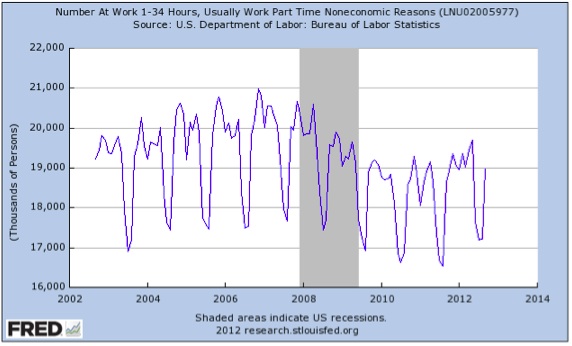

And it makes sense, at least to me, that the number of part-timers rises in September. There is something in the American experience that says September is the time to go back to work. It comes from our public school system, which traditionally had the school year beginning in September. You can see this phenomenon when you look at the non-seasonally adjusted numbers for part-time workers. They show a big drop-off in summer and a correspondingly big increase in the fall. Look at how volatile the annual numbers have been for the last 10 years. And we can show the same thing for the last 60 years. (This is one of the reasons why we look at seasonally adjusted numbers rather than the volatile raw data.)

People graduating from college, for instance, might spend the summer looking for a job, but when September rolls around they take what they can get, even if it is a part-time job.

The Really Important Employment Numbers

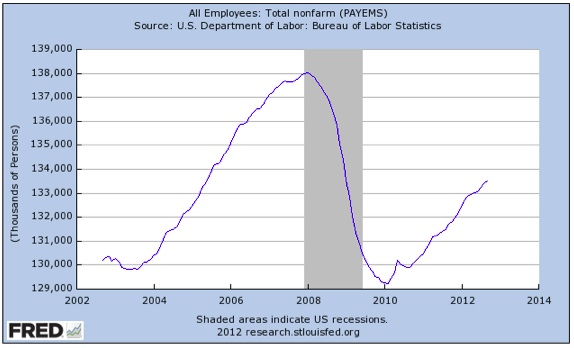

Look at the next few charts. What they show is the devastation from the last recession. There is a reason that people call it the Great Recession.

“We’ve now regained close to half – 48% – of the jobs lost between December 2007 and February 2010 (the low in employment, eight months after the recession’s formal end). It’s still going to take about 40 months at current rates of job growth to regain all the losses, but it’s worth acknowledging the progress that’s been made. (The Liscio Report)

Note that we regain all the losses only if there is not a recession in the next 40 months. If there is a recession, recovery will take even longer as we once again lose more jobs. Now, we’re back only to roughly where we were at the beginning of 2009, when Obama took office.

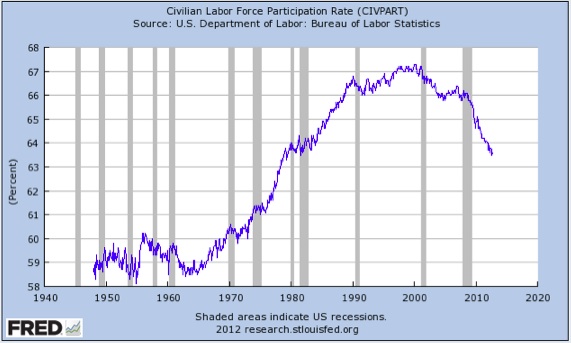

The labor-force participation rate is now below where it was in 1980. This statistic has been in decline for 12 years, and precipitously so since the beginning of 2008.

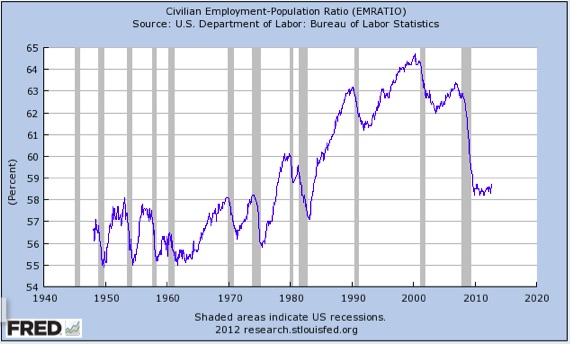

Even more distressing is the civilian employment-to-population ratio. While it might only take us another four years or more to get back to the number of jobs that we had in 2007, the population is growing each and every year; so it is going to take us even longer to get anywhere close to the ’07 employment-to-population ratio. Five years? Seven years? Ten years?

The unemployment rate is a function of the number of people looking for work and/or participating in the labor force. The drop of 2.5% in the participation rate masks the severity of the unemployment rate. Do we really think that, since 2007, 2.5% of the population has decided they don’t want a job?

We are employing almost 5% fewer people as a percentage of our population than we were at the beginning of 2008. That means our real unemployment-to-population level is well over 12%. So we’re not even close to where we were in 1999, during the last year of the Clinton administration.

And that doesn’t take into account the 50% of college graduates who are underemployed.

A significant part of the problem is simply the fact that we are trying to recover from a deleveraging recession. The data suggests that such recoveries may take 10 years. For Japan it is more than 20 years, and counting.

The solution, of course, is to once again grow the economy over 3% per year for a decade, as we did for the 60 years following the Great Depression and for almost the last two centuries, up till the beginning of the new millennium. This is something we have not done for 12 years, averaging much less than 2%. Analysts are now estimating that corporate earnings were down for the last quarter. Yet it is the private sector that we need to both create jobs and to generate additional income that will enable us to afford the level of government that we want.

Increasing oil and gas production will help, of course, especially if we can turn natural gas into chemicals made in the US for export. But we will need whole new industries, just as computers created such growth in the ’80s and ’90s. And of course we must rein in the size of government and our deficit. But those are topics we’ll return to in another letter (and book!).

Portland, Chicago, Atlanta, and South America

I fly some 60-80 times a year. I have to say I was rather surprised to hear Al Gore suggest that it was perhaps the altitude of Denver that was responsible for Obama’s off night. I can remember landing in Denver and speaking two hours later and being just fine. Then again, I have flown into cities at sea level and been flat as a pancake. I don’t think it happens often, and I’m not sure of the reasons, but sometimes I am just not as sharp as usual on the podium. It happens to the best of speakers. Obama still has two debates to go. I know style counts, but I would like to think that most Americans were listening to the discussion of the issues. We’re not voting for class president. The decisions that the next president makes will affect us profoundly.

I leave Wednesday morning to go to Portland to speak for Common Sense Investments, and they have invited me to stay the next day and go pheasant hunting. I will get to be with my good friend and hedge fund manager Kyle Bass, whose insights I greatly admire. The next week I will be in Chicago, once again speaking for Common Sense Investments, and then move on to Atlanta to speak at Hedge Funds Care. Then it’s home for a week before I ship off to South America at the end of the month (Sao Paulo, Montevideo, and Buenos Aires).

To help do our part in creating job growth, Mauldin Economics is looking for a high-quality marketing copywriter to assist us with writing assignments related to our letters. Rather than send a resumé, I’d like to encourage experienced candidates to submit a short sample (250-500 words max) of their writing, along with their contact information. The team will review your work and, if we are interested, we’ll contact you. Candidates should have an understanding of finance, economics, and direct marketing, and ample respect for my readers. In other words, fraudsters and hypers need not apply. You can contact us at Talent@MauldinEconomics.com.

This coming weekend I really do want to get down to Houston for my 40th Rice University class reunion. It also coincides with Rice’s centennial year, so there will be lots of interesting things going on, as well as many old friends to reconnect with. I turned 63 last week, and as I was graduating from Rice, that age sounded rather ancient. Now I feel like I am just hitting my stride, albeit with a few more aches and pains in the joints than 40 years ago.

It really is time to hit the send button. I had to go to Houston yesterday (Sunday), so I got started rather late on my first day of writing this letter on what was supposed to be Sunday afternoon. Oh well, the best laid plans and all that. Have a great week, and thanks for your comments and suggestions. I do read them.

Your looking forward to the next 40 analyst,

John Mauldin

What's been said:

Discussions found on the web: