Sorting Out the Decade

John Mauldin

December 15, 2012

In today’s Outside the Box I bring you two pieces that, at first glance, may not seem to have much to do with each other. First, Bill Gross, PIMCO managing director, runs down the fierce structural headwinds that our hard-pedaling global economy faces over the next decade. I am going to deal at length with not only his GDP projections for the rest of the decade but those of Grantham and others in the last two Thoughts from the Frontline of this year. This is a challenging environment for traditional portfolio construction, but it’s par for the course as we slog through the secular bear market I was first writing about in 1999.

In today’s Outside the Box I bring you two pieces that, at first glance, may not seem to have much to do with each other. First, Bill Gross, PIMCO managing director, runs down the fierce structural headwinds that our hard-pedaling global economy faces over the next decade. I am going to deal at length with not only his GDP projections for the rest of the decade but those of Grantham and others in the last two Thoughts from the Frontline of this year. This is a challenging environment for traditional portfolio construction, but it’s par for the course as we slog through the secular bear market I was first writing about in 1999.

Then Charles Gave instructs us on the distortions in the measurement of risk that have been introduced as the “plain, boring and well-meaning economists working in the entrails of the world central banks” have supplanted the Marxist avant garde in the world’s shift away from “scientific socialism” to “scientific capitalism.”

However, when you think about it, these pieces dovetail in a very convincing – and somewhat frightening – manner. Because what they add up to – if the econocrats are yanking the rug out from under a capitalist system that is already reeling, as Gross says, from debt and deleveraging, a slowing of the locomotive of globalization, and dislocations in technology and demographics – is a profound, ongoing challenge to you and me as investors. Gross and Gave have their own ideas about how we get through this. I don’t agree with all their conclusions – this letter is not called Outside the Box for nothing – but I offer these essays because they’ll make us think through our own presuppositions. However you view their analysis, they do reinforce the idea that we’re all going to have to be not only careful but very nimble.

I post this note from 35,000, feet flying back from Cleveland to Dallas. American Airlines has now put internet on nearly all of their domestic flights, and I find the time I spend read and respond without interruption up here some of the more productive time I get. Which is good, since the record shows that I have been on some 110-plus different planes this year, most of which were AA. (Lately, when I am asked where I live, I just say my closet is in Dallas.)

It is not just me but other “road warriors” who have noticed that the staff of AA have markedly stepped up their personal service levels (as opposed to United, when they were in similar financial difficulties). More than a few of their employees have gone far out of their way to make my difficult travel schedule a little bit easier and smoother, from frontline staff to their back-office phone mavens, who often perform a little bit of magic rearranging my schedule. And as they add newer planes to their fleet, seat 5B has almost become my home office. So here’s a tip of the hat to them and all the service people who make life on the road better. And may your own road be a little smoother these holidays.

I spent last night at Dr. Mike Roizen’s home before seeing a few doctors at the Cleveland Clinic. I rode in a limo with him to a speech in Youngstown, Ohio, and we had time to visit at length. Mike has become one of my dearest friends, and our times together are easy ones, deeply treasured. Without this peripatetic life I would not have so many good friends, far and wide. It is the best perk of traveling.

Mike is on the board of the Cleveland Clinic, and he is deeply worried about the fiscal cliff. Even assuming the “doc fix” is passed, as it always is, without an alteration or repeal of the current law, the Cleveland Clinic will be faced with an almost 9% budget cut on January 1. They will lose money on every Medicare and Medicaid patient they see. There are no good solutions other than deep budgets cuts. And since the largest portion of their budget is salaries?…

The CC is held up (rightly so) as one of the most efficient medical organizations in the world. They have no fat to cut. I met the lady, in my walking around at the clinic, who cut $24 million in energy costs and another $2 million in trash-removal costs, at some considerable effort and investment. They leave no dollar stone unturned in the pursuit of efficiency.

Mike and I talked deep into the night and much of the next day, when we could, about our healthcare system. It fills me with deep concern. I have asked Mike to give us an outline of his speech today for an Outside the Box. His five-step “solution” has lowered healthcare costs for the 43,000 CC staff and all firms that have adopted their plan. When you look at his numbers, you understand why the US spends more money on healthcare than Europe. We are indeed that much less healthy. The CC has found out that paying each staff member $2,000 to adopt a healthier lifestyle lowers overall costs by even more than that.

Smoking cigarettes may be your personal choice and God-given right, but it costs the American healthcare system and taxpayers multiple tens of billions. And the same goes for four other lifestyle habits. Want to live long and prosper? And be smarter and have better sex? Just eat right, exercise and avoid a few items. I hope Mike gets me that essay soon, as I want all my closest friends (that would be you!) to stay around with me for a long, long time.

Have a good week. I am looking forward to the holidays and home and family. And while I try to get exercise on the road, my home gym is still the best.

Your ready for a few good nights’ sleep in my own bed analyst,

John Mauldin, Editor

Outside the Box

subscribers@mauldineconomics.com

Strawberry Fields – Forever?

Bill Gross, Managing Director, PIMCO

Living is easy with eyes closed

Misunderstanding all you see

I think I know I mean a yes

But it’s all wrong

That is I think I disagreeStrawberry Fields Forever

The Beatles

You didn’t build that…………… 332

I built that …………………………….. 206

Well, I guess that settles it: you didn’t build that after all. Or maybe you did, but not all of it. Or maybe like the convoluted John Lennon above “you think you know a yes, but it’s all wrong. That is you think you disagree.” Whatever. Rather than an economic mandate, November’s election was more of social commentary on the Republicans’ habit of living with eyes closed. Their positions on what Conan O’Brien labeled “female body parts” – immigration, gay rights and student loans – proved to be big losers, and they will have to amend rather than defend those views if they expect to compete in 2016. I suspect they will. Political parties are living social organisms that mutate in order to survive. We will see straight talking Chris Christie or Hispanic flavored Marco Rubio leading the Republican charge four years from now versus a reenergized Hillary Clinton. It should be quite a show with a “No Country for Old (White) Men” caste to it.

But whoever succeeds President Obama, the next four years will likely face structural economic headwinds that will frustrate the American public. “Happy days are here again” was the refrain of FDR in the Depression, but the theme song from 2012 and beyond may more closely resemble Strawberry Fields Forever, as Lennon laments “It’s getting hard to be someone but it all works out.” Why is it so hard to be someone these days, to pay for college, get a good-paying job and retire comfortably? That really was the economic question of the 2012 election towards which very few specifics were applied from either side. “There’s a better life out there for us,” Governor Romney bellowed to a crowd of thousands in

Des Moines, Iowa just days before the election, but in truth he never told us how we were going to achieve it or, importantly, why we weren’t realizing it in the first place. The president’s political mantra of “Forward” was even more vague.

Their words were mum if only because the real cause of slower economic growth lies hidden in a number of structural as opposed to cyclical headwinds that may be hard to reverse. While there are growth potions that undoubtedly can reduce the fever, there may be no miracle policy drugs this time around to provide the inevitable cures of prior decades. These structural headwinds cannot just be wished away as we move “forward” whether it be to the right, the left or dead center. Last month in a major policy speech at the New York Economic Club, Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke concurred that the U.S. economy’s growth potential had been reduced “at least for a time.” He in effect confirmed PIMCO’s New Normal which has been in place for three years now, laying the blame in part on the financial crisis, diminished productivity gains, and investment uncertainty due to the near-term fiscal cliff. We do not disagree. However, there are numerous other structural headwinds that may reduce real growth even below the New Normal 2% rate that Bernanke has just confirmed, not only in the U.S. but in developed economies everywhere.

They are:

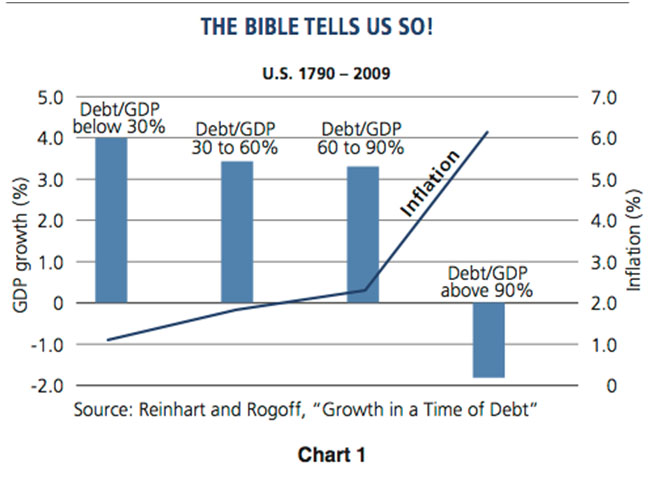

1) Debt/Delevering

Developed global economies have too much debt – pure and simple – and as we attempt to resolve the dilemma, the resultant austerity should lower real growth for years to come. There are those that believe in the “Brylcreem” approach to budget balancing – “a little dab‘ll do ya.” Just knock a few percentage points off the deficit/GDP ratio, they claim, and the private sector will miraculously reappear to fill the gap. No such luck after 2–3 years of austerity in Euroland, however. Most of those countries are mired in recession and/ or depression. Political leaders there should have studied the historical evidence presented by Carmen Reinhart and Ken Rogoff in a critically important paper titled, “Growth in a Time of Debt.” They conclude that for the past 200 years, once a country exceeded a 90% debt/GDP ratio, economic growth slowed by nearly 2% for both developed and developing nations for an average duration of nearly a decade. Their work displayed below in Chart 1 shows the result in the United States from 1790–2009. The average annual U.S. GDP rate growth, while clearly influenced by the Great Depression, was -1.8% once the 90% barrier was exceeded. The U.S., by the way, is now at a 100% debt/GDP ratio on the basis of the authors’ standard measuring yardstick. (Note as well the 5_% average inflation rate during the same periods.)

In addition to sovereign debt levels which were the primary focus of the Reinhart/Rogoff studies, it is clear that financial institutions and households face similar growth headwinds. The former needs to raise equity via retained earnings and the latter to increase savings in order to stabilize family balance sheets. The combined need to increase our “net national savings rate” highlighted in last month’s Investment Outlook is a long-term solution to the debt crisis, but a near/ intermediate-term growth inhibitor. The biblical metaphor of seven years of fat leading to seven years of lean may be quite apropos in the current case with the observation that the developed world’s growth binge has been decades in the making. We may need at least a decade for the healing.

2) Globalization

Globalization has been an historical growth stimulant, but if it slows, then the caffeine may wear off. The fall of the Iron Curtain in the late 1980s and the emergence of capitalistic China at nearly the same time was a locomotive of significant proportions. Adding two billion consumers to the menu made for a prosperous restaurant, increasing profits and growth in developed economies despite the negative internal effects on employment and wages. Now, however, these tailwinds are diminishing, producing an airspeed which inexorably slows relative to the standards of prior decades. Is it any wonder that markets now move up or down as much on the basis of policy changes coming out of China as opposed to the U.S. or Euroland? If China and the accompanying benefits of globalization slow, so too may developed economy growth rates.

3) Technology

Technology has been a boon to productivity and therefore real economic growth, but it has its shady side. In the past decade, machines and robotics have rather silently replaced humans, as the U.S. and other advanced economies have sought to counter the influence of cheap Asian labor. Almost a century ago, Keynes alerted the economic community to a “new disease,” what he called “technological unemployment” where jobs couldn’t be replaced as fast as they were being destroyed by automation. Recently, Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee at MIT have affirmed that workers are losing the race against the machine. Accountants, machinists, medical technicians, even software writers that write the software for “machines” are being displaced without upscaled replacement jobs. Retrain, rehire into higher paying and value-added jobs? That may be the political myth of the modern era. There aren’t enough of those jobs. A structurally higher unemployment rate of 7% or more is the feared “whisper” number in Fed circles. Technology may be leading to slower, not faster economic growth despite its productive benefits.

4) Demographics

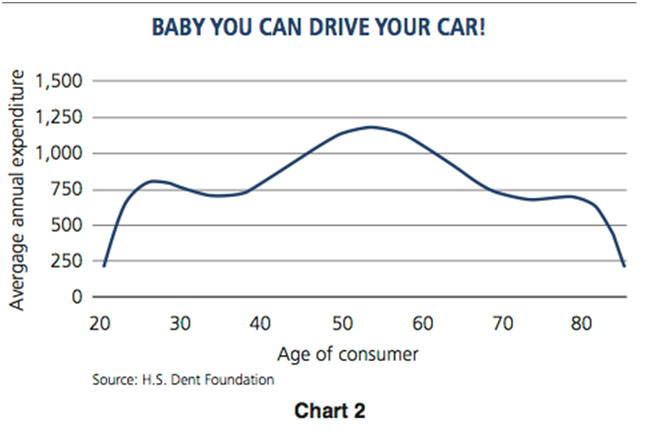

Demography is destiny, and like cancer, demographic population changes are becoming a silent growth killer. Numerous studies and common sense logic point to the inevitable conclusion that when an economic society exceeds a certain average “age” then demand slows. Typically the dynamic cohort of an economy is its 20 to 55-year-old age group. They are the ones who form households, have families and gain increasing experience and knowhow in their jobs. Now, however, almost all developed economies, including the U.S., are gradually aging and witnessing a larger and larger percentage of their adult population move past the critical 55-year-old mark. This means several things for economic growth: First of all from the supply side, it means productivity and employment growth rates will slow. From the demand side, it suggests a greater emphasis on savings and reduced consumption. Those approaching their seventh decade need fewer cars and new homes as shown in Chart 2. Almost none of them have babies (thank goodness!). Such low birth rates and a significant reduction in demand have imperiled Japan for several lost decades now. A similar experience will likely turn many developed economy “boomers” into “busters” within the next several years.

Investment Conclusions

I’m fond of reminding PIMCO’s Investment Committee that you can’t buy GDP futures – at least not yet. Hypotheses about real growth rates, no matter how accurate, must be translated into investment decisions in order to justify the discussion. Before doing so, let me acknowledge that these structural headwinds can and will likely be somewhat countered by positive thrusts. Cheaper natural gas and the possibility of reversing or even containing the 40-year upward trend of energy costs may be a boon to productivity and therefore growth. There is talk of the U.S. being energy independent within a decade’s time. Housing as well may be experiencing a multiyear revival. In addition, unforeseen productivity breakthroughs may be just over the horizon. How many gloomsters could have forecast the Internet or any other technical breakthrough before it actually happened? Jules Verne we are not.

But if a 2% or lower real growth forecast holds for most of the developed world over the foreseeable future, then it is clear that there will be investment consequences. Shown below, as recently published in a TIME Magazine article by Rana Foroohar, is a PIMCO list of future Picks and Pans based upon these ongoing structural changes:

Picks

· Commodities like Oil and Gold

· U.S. Inflation-Protected Bonds

· High-Quality Municipal Bonds

· Non-Dollar Emerging-Market Stocks

Pans

· Long-Dated Developed-Country Bonds in the U.S., U.K. and Germany

· High-Yield Bonds

· Financial Stocks of Banks and Insurance Companies

The list to a considerable extent reflects the view that emerging economy growth will continue to be higher than that of developed countries. Their debt on average will remain much lower, and their demographic age much younger. In addition, the inevitable policy response of developed economies to slower growth will be to reflate in order to minimize the impact of the aforementioned structural headwinds. If successful, reflationary policies will gradually move 10 to 30-year yields higher over the next several years. The 30-year Treasury hit its secular low of 2.50% in July and such a yield may seem ludicrous a decade hence. Investors should expect future annualized bond returns of 3–4% at best and equity returns only a few percentage points higher.

As John Lennon forewarned, it is getting harder to be someone, and harder to maintain the economic growth that investors have become accustomed to. The New Normal, like Strawberry Fields will “take you down” and lower your expectation of future asset returns. It may not last “forever” but it will be with us for a long, long time.

The Control Engineers and the Notion of Risk

Charles Gave, GaveKal

There is a great movie scene where Harpo and Groucho Marx meet in the “socialist restaurant.” Groucho says, “this food is disgusting and inedible!” To which Harpo replies, “and on top of that, the portions are far too small!” So by the late 1930s and the golden era of the Marx Brothers, it was already obvious that socialism was bad fare in high demand. Yet it took another half century for “scientific socialism” to be finally discredited in rivers of blood, murder and poverty. With the economic disasters wrought by socialism, one might have assumed that policymakers would accept that the future cannot be forecasted. The role of economists, governments and central banks is to promote a stable monetary and legal framework for the risk-takers (entrepreneurs, money managers etc.) to make their decisions as rationally as they could.

Unfortunately this has not happened. Instead, in a new and improved declination of Friedrich Hayek’s “fatal conceit,” we seem to be moving away from “scientific socialism” to “scientific capitalism” – where the overconfident and overeducated control-engineers are no longer members of the avant garde of the proletariat, but plain, boring and well-meaning economists working in the entrails of the world central banks. My intent is not to show why these economists will fail (bigger and brighter minds such as Hayek, Mises, Friedman, etc. have already done this) – but rather to review the impact that the misguided manipulation of the price of money (exchange and interest rates) is having on the notion of risk.

In standard financial theory, most practitioners use the volatility of underlying assets as a measure of risk. To some extent, quantitative easing policies have had their biggest impact on this measure. Not only are prices totally artificial for a number of assets (government debt chief amongst them), but the volatility of these prices is also completely meaningless. Volatility no longer indicates the risks involved in holding certain assets, but instead measures the amount of the manipulation that the poor prices are enduring. For example, no-one today could say with a straight face that there is any information in the volatility of the euro-swiss exchange rate, or that this zero volatility adequately measures the risks that a Swiss based investor takes in buying euro-denominated assets.

So as a direct consequence of the manipulations of our well-meaning “control engineers” of market prices, today’s volatility readings have absolutely nothing to do with the underlying risks. From here, it is hard to escape the following conclusions:

· This will lead to the next disaster, for major financial accidents typically find their source in a misconception of risks, rather than a misconception of returns (e.g., Greek bonds are just as risky as German bonds, levered US mortgage bonds are as safe as houses, etc).

· Building a rational portfolio, where risks can be properly hedged, is almost impossible when market signals have disappeared (explaining the recent difficulties of so many macro and CTA hedge funds?).

Staying with the above ideas, consider that all the quantitative models and statistical techniques like “value at risk” will prove to be hopelessly wrong when true volatilities re-emerge (as they always do!). And when that occurs, who doubts that many financial institutions will, once again, find themselves in the line of fire. After all, as Karl Popper explained: “In an economic system, if the goal of the authorities is to reduce some particular risks, then the sum of all these suppressed risks will reappear one day through a massive increase in the systemic risk and this will happen because the future is unknowable”. The sum of the risks in an economic system over time is a constant and the only question confronting economists is whether we should prefer to take our risk in small doses, or in a massive injection (as occurs when a fixed exchange rate system breaks down, or when a debt restructuring happens etc…)?

So in a world of “suppressed volatility,” the only smart thing a long-term investor can do is to buy the assets which have been sold because of their higher volatilities. This obviously is equities, and in particular, the very long duration equities of companies in technology, healthcare, energy, etc. A well-diversified portfolio of such shares will be volatile, but investors will likely see their money back over time and then some.

In fact, strange as it may seem, the only way to reduce the risk today is to own assets that still sport a “market price” – which will thus automatically have a very high volatility compared to the other assets exhibiting a very low, but artificial volatility. To reduce risk today, one has to build a very volatile portfolio! This is partly because a lot of non-volatile assets are extraordinarily risky. For example, I cannot think of more dangerous assets to own today than French or Japanese government bonds. I could easily imagine Groucho looking at a menu of JGBs and OATs and exclaiming, “these assets are terrible and have no yield”, only for Harpo to reply, “and their aren’t enough for everybody.” This last line will change rapidly when reality hits. Because economic history teaches us that no policymaker can control volatility for ever. The real hedge for portfolios today no longer is government fixed income, or even gold, but is instead volatility strategies.