This piece seeks to make the economic case for savers to allocate wealth to physical gold (in proper form) and for investors to allocate capital to precious metal miners. Our argument orients readers with our economic and market predispositions, seeks to explain current macroeconomic events within that context, outlines gold’s fundamental valuation framework, and then applies that framework to gold and various financial asset investment choices. The piece is long and may be best consumed at home.

Hypothesis: Due to decades of unreserved credit growth that temporarily boosted the appearance of sustainable economic growth and prosperity, rational economic behavior cannot produce real (inflation-adjusted) output growth from current levels. The nominal sizes of advanced economies have grown far larger than the rational scope of production that would be needed to sustain them. This fundamental problem explains best the current state of affairs: economic malaise spreading through the means of production and the need for increasing policy intervention to stabilize goods, service and asset prices.

Observations

- Most of the last forty years represented a golden age of financial asset investing that is unlikely to be repeated for a very long time. Consider that the last generation benefitted greatly from a unique combination of factors, including:

- a global monetary system that for the first time (1971) allowed currency to be created entirely in the banking system through lending activities, without material constraint

- a generation of declining global interest rates coincident with perpetually easy credit conditions (beginning in 1981)

- very little initial debt on household and government balance sheets as a percentage of assets and income (i.e., leverage-able balance sheets)

- the building need for post-war baby boomers to invest for retirement

- the advent and maturing of asset securitization, asset-backed securities, and the high yield bond market, which broadly expanded systemic credit and debt distribution

- new market technologies that reduced trading and monitoring costs and provided greater access to equity and fixed income markets

- great technological and scientific innovations with commercial applications, which captured equity investor imaginations

- the opening of previously closed large economies to Western commerce and financial assets

- economic policies seeking near-term nominal GDP growth as a first priority, including central bank backstopping of market losses

- The combination of factors above set the stage for a financial asset investment culture in which the markets could emphasize nominal growth over real growth and risk-adjusted profitability. (Indeed, record credit creation and debt assumption demanded that economies sustain asset price inflation so the value of bank loan books and bond portfolios could be sustained.)

- Established equity indexes, weighted by market capitalization, further motivated equity market investors to seek nominal growth and de-emphasize real profits. Because most dedicated equity investors, such as pension and mutual funds, endowments, foundations, insurers, etc., judge their performance against these indexes; the great majority of sponsoring capital in the stock market has had incentive to reward increasing market caps over increasing profitability. (And although more independent investors have been in the position to try to time and re-allocate their investments more freely than indexed or closet indexed investors, they too have been unable to escape the pull of general market behavior towards increasing market caps.)

- The emphasis on ever-increasing market caps further directed the incentive structure among listed businesses to continually increase their market caps. Top-line revenue is most easily increased by leveraging corporate balance sheets. The values of publicly traded businesses were generally punished when they shrunk their revenues to become profitable. (Private businesses, on the other hand, were under no such pressures and could behave rationally.) Thus, competition for market share and investor sponsorship accelerated corporate debt assumption as a secular business model.

Despite being major shareholders of publicly traded companies, professional asset managers are compensated through a percentage of the nominally priced assets they manage. As a result, they too have had commercial disincentive to encourage public businesses they have stakes in to emphasize profits over market cap growth (unless they are already distressed), and have no incentive to lobby equity index publishers to change the way they calculate their indexes. Equity markets, theoretically meant to 1) aid in forming capital and 2) perpetually price the value of the means of producing that capital, instead gradually came to ignore return-on-capital metrics in favor of quarterly share performance. Real return investing is now largely ignored.

- There is no longer an economic “message of the market.” As a result of the financial market incentives and their influence over business behavior noted above, it has become reasonable to separate nominal stock market performance from real economic growth and the expectations for it. More recently, derivative and technology-driven equity trading strategies have boosted trade volume many times its organic level, and central bank financial repression (i.e., bond monetization) has supported bond and stock prices (i.e., bigness). These trends have further obscured economic signals the markets historically provided.

Presently, there are no public financial markets that value businesses or future income streams within the context of capital formation of their broader economies. Financial markets have become discrete exchanges of abstract relative value in which “investors” are forced to chase short-term relative nominal returns.

- There is no commonly perceived place to save risk-free. Saving at a bank has not been a rational alternative to investing in financial markets given that modern economies have inflationary models supported by perpetually easy credit conditions. This, in turn, has ensured diminishing purchasing power for savers of modern currencies. Only recently (2008) has this become obvious. Central banks’ zero interest rate policies (“ZIRPs”) have pinned benchmark interest rates near zero, producing obvious negative real interest rates. Thus, conventionally storing one’s wealth in cash or in fixed-income instruments offers little or no sanctuary for unlevered investors looking to maintain or increase future purchasing power.

- The almost complete blending of financial markets with financial media has lent the markets a patina of transparency, constancy and stability. Financial media provides market (not commercial) news to a small niche audience (CNBC’s “Squawk Box” reaches only 150,000 viewers on a good day[2]), and serves as a platform for monetary and fiscal policy communications. Major corporate earnings and economic data releases have come to resemble made-for-TV sporting events and provide a thin financial narrative. Thus, a small investor class controlling significant perceived wealth is forced to abide by consensus macroeconomic perceptions, which do not necessarily reflect true structural commercial and economic forces.

- Organizations that produce economic data are closely tied to organizations executing fiscal and monetary policies. Whether or not the data are managed or manipulated, as is increasingly suspected by observers, they are produced and released in a manner that evokes predictable responses from financial markets, which in turn send popularly understood (yet potentially erroneous or incomplete) economic signals. The net result for economic policy makers is that their policies are relatively easy to sell to the public. A declining headline unemployment rate or increasing home sales figures are positive political and media events, regardless of declining employment participation rates or stagnant mortgage applications, and regardless of the millions of people experiencing lifestyle distress in diametric opposition to what the data imply.

- The common perception of economic and commercial health established by policy makers through financial management and media, and supported by financial market participants, defines ongoing economic and commercial reality, regardless of whether it is sustainable.

Analysis: These observations lead us to the unscientific conclusion that we live and work in a contrived meta-economy that can be managed through narrow channels in financial and state capitals. We do not dispute that perception is reality; however, we argue there is growing social dissension from the significant gap separating the popular perception of self-determinism through free markets (and the sustainability of economic cyclicality and wealth that implies), from the burgeoning awareness that the sustainable values of our production and assets are being managed, and that the current trajectory of our economies might not support the future needs and expectations of the masses.

Over time our meta-economies have produced great debt and economic malinvestment (too many homes and home contractors, not enough competitive manufacturing; too much insurance, not enough affordable health care; too many bond traders, not enough engineers), and a boom/bust global economic model that may be more accurately defined as an oscillating leveraging cycle (discussed in more detail un “Burning Matches,” below). Future “prosperity” now relies on a battery of central bankers directing monetary policies consistent with the expectations of their sponsoring banking systems and governments, which, in turn, implies that the best interests of the means of production, savers, and unlevered investors are in line with those of their banking systems and governments.

The weight of overwhelming evidence does not bear this presumption out. The balance sheets of governments and of banks and other levered investors have clearly taken priority over the masses they ostensibly serve. Consider that as economies are de-leveraging, nominal entities (those perpetually leveraged, such as banks) are the recipient of central bank policy support (e.g., bank reserve creation via targeted asset purchases). Governments that failed to properly regulate banking systems’ credit policies and that failed to enforce fiscal policies consistent with the long-term sustainability of their economies have been aggressively seeking relief from central bank money creation capabilities as well as from their non-bank private sectors (e.g., the Cyprus bail-in, which confiscates bank deposits, and fiscal provisions like the 2014 White House budget, which proposes capping retirement savings). Meanwhile, un-levered savers and investors suffer and are left to manage their own affairs.

To be clear, credit for a significant portion of past prosperity, as well as blame for the widespread, unsustainable economic leverage it has led to today, rests with the entire political spectra across modern liberal democracies that perpetuated finance-based economies incapable of serving their societies’ long-term interests. Such is the social cognitive dissonance of over-levered societies living under over-levered governments.

Simply, “prosperity” was pulled forward through economic leveraging and the only ways to reconcile that now are to either let the general price level (GPL) deflate or to inflate the quantity of the total money stock (which deflates the value of labor, goods, services and assets in real terms to varying relative degrees). Conventional fiscal or monetary policy solutions cannot fix what ails over-levered global economies today. This implies any notion of economic or market cyclicality is misguided.

It is obvious that global economic and market environments are in great transition, no longer defined by financial cycles, and it is further obvious (to some) that fiscal and monetary policy makers are almost out of unconventional ideas. Debtor governments are funding themselves through the almost infinite balance sheets of central banks. Financial asset markets are being funded by newly created bank reserves and the noblesse oblige of captive dedicated investors mandated to seek relative nominal returns, rather than investing with an eye toward capital formation and purchasing power enhancement. It is against this backdrop that we ask the question: are there really unpredictable market shocks or are investors not paid to care?

We believe most investors today intuit the following: the global financial asset markets have captured virtually all of the perceived wealth in the West => as a result, the markets’ health and continued funding has become the first priority of policy makers => this perceived economic imperative allows monetary policy makers to ensure their economies do not contract in nominal terms (without regard for real growth or real return-on-assets) => the smart play (i.e., “the wisdom of crowds”) suggests it is wisest to keep one’s wealth in levered financial markets.

The crowd is ignoring the obvious and will miss great opportunity, in our view. Today’s negative real interest rates amid one of the most inflationary global monetary regimes on record presents a rare chance to capture significant Alpha if/when the monetary system resets again (which we argue it must).

Given the overwhelming past misallocation of capital cited above, we think the most important realization for investors in the current environment is that price levels of goods, services and assets may be biased to rise but they are not sustainable in real terms. Due to the unknowable sustainable value of the currencies in which they are denominated, projected growth rates are only meaningful relative to each other. So, financial assets do not necessarily provide a path to secular capital or wealth creation, only to coincident relative financial returns amid ever increasing currency dilution. The real value of interest rates and all investables should be calculated by discounting nominal rates and asset prices by past and necessary future money stock growth (reserves plus unreserved deposits). (Please see “Gold as a Rational Investment in Advance of Manifest Inflation,” below.)

Burning Matches (Macroeconomic Observations)

The prospects for global economies rely on the supply of money and credit – who has which and when they get it. Within this environment, it seems clear that advanced economies are circling the wagons around the current monetary system. Consider the following:

- ECB-imposed austerity on peripheral nations is effectively a means of strengthening core European bank balance sheets (by reducing the ratio of Euro-denominated unreserved deposit money to bank reserves), which shifts wealth from the periphery to the core

- BOJ inflation targeting temporarily maintains Japanese bank viability (by reducing the ratio of Yen-denominated unreserved deposit money to bank reserves), and, by temporarily weakening the Yen relative to other currencies, temporarily shifts relative wealth from Yen-denominated savers to shareholders of Yen-denominated exporters

- Fed QE de-leverages US bank balance sheets (by reducing the ratio of USD-denominated unreserved deposit money to bank reserves), and, as a monetary operation using the world’s hegemonic reserve currency, temporarily shifts relative wealth from all global savers to USD-denominated financial asset investors

We doubt there would be meaningful disagreement from serious analysts regarding the considerations above, although most policy makers and economists would argue that such monetary operations are necessary in the context of the alternative, which would be to do nothing and let valuations find their natural clearing levels (i.e., asset and unreserved credit deflation and economic contraction). The burning question of the day has been (for many days now): “how long can these operations continue before monetary authorities withdraw their support and let economies function more independently?”

We believe the simple answer to that question is “never, or at least not until the global monetary system is reset.” Simply, there is a dearth of the transactional money stock[1] needed to service and repay outstanding obligations, both in the banking system (deposits) and among non-bank borrowers (governments and households). This transactional money stock is being used increasingly to service and repay debts, which in turn is crowding out its use in normal goods and service transactions. This crowding out further pressures lower the general price level (GPL) of goods and services and reduces support for labor and asset prices. Thus, we think 1) monetary authorities must continue to increase the base money stock in perpetuity in an attempt to maintain the nominal money stock and nominal economic output, and/or 2) users of the transactional money stock must, in aggregate, begin to re-leverage their balance sheets further so they may continue servicing their debt while consuming more goods, services and assets.

Any meaningful balance sheet reduction (assets and liabilities) in either the banking system or among non-bank lenders and borrowers implies immediate economic contraction, widespread bank insolvencies, and bankruptcies. While the EU has room to impose austerity on peripheral countries due to its lack of fiscal union (political cover from cultural separation), Japan and the US do not. (In this, the troika still has a means of de-levering banks domiciled in the core without ECB base money creation – by seizing deposits in, and haircutting other unsecured lenders to, peripheral banks.)

Meanwhile, Japan seems to be benefitting temporarily from an increase in nominal asset pricing since the BOJ formally embarked on its inflation targeting regime. The benefits to Yen-based exporters and investors are obvious in nominal terms; however when they convert the proceeds of nominal benefits from currency weakness back into global resources, goods and services, those benefits are likely to be marginal at best. Continuing Fed QE also seems to be temporarily sustaining nominal USD-denominated asset prices (by removing duration risk from the markets) and economies, more or less; however, it does not seem to be increasing the portion of the transactional money stock (deposits and cash) that supports increasing goods and service activity.

Many observers seem to conflate leveraging with inflation and deflation with de-leveraging. This mistake further seems to have led to miscalculations of economic cause and effect and asset values. Put simply, there is the horizontal notion of the quantity of the money stock and the vertical notion of bank system leverage. These overlying notions are represented by the box below using the US banking system as an example:

The box is meant to separate trending inflation or deflation from trending systemic leveraging or de-leveraging; the point being the two dynamics and four potential combinations are different and have very different implications. Together, a banking system and its economy can be residing any one of the quadrants at any given time, but only one.

The Fed and other policy makers are in a bit of a quandary presently. Clearly, the preferred state of being for the health of the banking system and the proliferation of public deficit spending is the top right quadrant (inflationary leveraging). In this scenario (1982 to 2007), bank income statements and the collateral supporting their loan books inflate in nominal terms against their fixed, nominal liabilities. In 2008, irreconcilable leverage forced the US and global economies to slip into the lower left quadrant. At some point between then and now we entered the upper left quadrant, where we remain today. The Fed and other central banks are working hard to de-leverage their banking systems by creating bank reserves (QE) amid the perception of a stable inflationary environment.

So, it seems obvious that the largest advanced economies are contracting in real terms and that their monetary authorities are boxed – forced to maintain their aggressive unconventional money creation policies just to sustain nominal asset prices and retard organic headwinds to economic growth. After years of ZIRP they can no longer try to generate increased demand through funding incentives. In our view, central banks are going to increase significantly their money creation programs and it is just a matter of time before they are forced to formally reset the global monetary system. They are holding burning matches.

Gold, Practically

There is a very rational reason for gold’s existence as a monetary asset, one that supports its increasing demand by private sector savers and central banks since 1999: gold stores future purchasing power at the price (i.e., exchange rate) at which it is swapped for fiat currencies. In light of this, and within the context of the preceding macro discussion, we find the recent activity in the paper and physical gold markets worth noting. Consider the following events and our interpretations:

- Significant and increasing central bank physical gold purchases: the recognition among currency reserve holders that current and necessary future central bank money creation implies those reserves (USD, BPS, EUR) will not maintain their purchasing power vis-à-vis global resources and other imports

- Prices of paper gold (i.e., unreserved claims on physical gold including futures, ETFs and gold swap agreements) are being hit hard in the markets at a time when central banks are ramping up fiat reserve printing and the global physical gold stock continues to be drained: a good way for paper gold shorts to try to cover and for large (sovereign?) buyers of physical gold to take delivery of more bullion

- Sudden downgrades of gold by Credit Suisse, Deutsche Bank, UBS, Goldman Sachs, Soc Gen, etc: eases conditions in which those short paper gold may cover

- Stocks of physical gold held at Comex warehouses (mostly those operated by JP Morgan and Scotia) declined by the largest amount on record last quarter (nearly 2 million ounces or about $3 billion), leaving Comex’s inventory with about 9.3 million ounces (or about $14 billion): size buyers of physical bullion, previously willing to amass it slowly due the relatively tiny physical gold stock, seem to be gaining incentive to increase their holdings expeditiously

- Record gold and silver ETF liquidations: physical gold held by ETF sponsors is being transferred to its bank custodians and ETF shareholder accounts are being credited with fiat cash

- Major Dutch bank, ABN AMRO, tells accounts holding unallocated gold (fractionally-reserved paper claims) that their accounts will be credited with cash in lieu of bullion: another sign of potential physical scarcity and conversion of weak-handed “gold holders” to fiat cash

- The ECB orders the Bank of Cyprus to pledge €400 million of gold to help fund its bailout: the first instance of gold monetization, and the first whiff of it in advance of fiat devaluation; (Cyprus pledges 200,000 ounces to the ECB, which equals about €400 million at current pricing [about €2,000/oz], but, at about €12,000/oz, the gold would equal €2.4 billion, which happens to be the remaining balance Cyprus owes after the Laiki bail-in)

Paper gold prices plunge 15% in two days at a time when; 1) global central banks are dramatically increasing global base money issuance, 2) central banks are large net buyers of physical gold, and 3) equity markets, which require global inflation, are at or near their highs: a paper gold financial event, a gift for buyers of bullion and shares of precious metal miners

Does it matter that total COMEX gold futures sales on April 12 and 15 was 12% more than total annual gold production? Are we looking for shadowy gold conspiracies where none exist? Are gold’s fifteen minutes (13 years) of fame finally over with the recent pullback of paper gold or do the nut-jobs in tin foil hats have it right? Anything’s possible, but it also should not go unnoticed that Kim Kardashian’s baby bump receives more accurate critical analysis than the forces behind secular global wealth positioning (not tactical financial asset market flows) and gold’s relevance in it.

Gold as a Rational Investment in Advance of Manifest Price Inflation

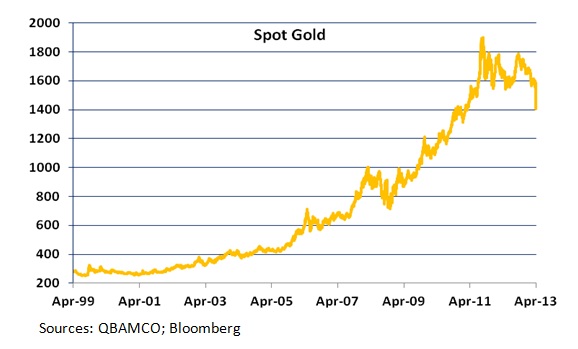

From the dot-com crash in 2000 through the housing boom and bust that followed, the spot gold price increased from $255/oz to about $1,400/oz presently. That 5.5-times appreciation compares with USD base money growth, also about 5.5-times over that span (from about $550 billion to about $3 trillion). Such a metric, however, is too simplistic and incomplete to be a reasonable baseline of “fair value” for the USD/XAU exchange rate because it does not include the growth of unreserved bank deposits – the unreserved credit currency we use for transactions and deposits in our checking accounts.

As we often point out, electronic credits used in transactions and deposited in our banking systems are many times the quantity of base money (the stock of bank reserves directly convertible to physical cash and physical currency already in float). Thus, most of what we commonly refer to as “money” today is in reality claims on base money that do not yet exist. The implication of this is that our money is mostly credit currency, in fact obligations of central banks to manufacture more base money upon demand (i.e., “cover the money short”). The implication of this, in turn, is that the more and longer economic activity and unreserved credit creation languish, the more base money central banks must create and the sooner they will have to begin focusing on the transactional money stock (introduced above and discussed below). This is the point where base money inflation turns into goods and service inflation rather than leveraged asset price inflation.

In the “Burning Matches” section above we introduced a transactional money stock (“TMS” = base money + M1 – cash) to show there is nowhere near enough usable deposits to service the significant amount of current and future claims on money (debt and unfunded obligations). Here, we argue that changes in composition of the TMS imply changes in relative asset values. Consider:

1) Money created as reserves requires that outstanding loan balances (deposits) contract in like fashion. This weakens prices of assets held on leverage and/or purchased with leverage.

2) Conversely, money created via loans (deposits) strengthens the relative prices of assets purchased with the newly-created deposits. (This is the leveraging process.)

Think of a teeter-totter whereby the existing money stock is the fulcrum. At one end of the teeter-totter are leveraged assets like stocks, bonds and real estate. At the other end is physical gold bullion. Physical gold is not only un-levered; practically it is inversely or negatively levered due to the preponderance of unallocated (unreserved) bullion balances held by unlevered gold longs. (Gold futures, ETFs and other forms of paper gold are, in the long term, a zero sum game and thus irrelevant to long term gold pricing – absent their utility as potential tools to influence short term physical pricing and deliveries.)

Theoretically, if leveraged asset prices deflate while the TMS is constant (although its composition changes via QE as per #1 above), then all things un-levered must rise in price and all things inversely-levered are biased to rise even further. Despite changes in money stock composition (increasing reserves offsetting decreasing deposits), the general price level (GPL) should remain constant as the total TMS remains constant (assuming further that confidence [i.e., velocity] in the stability of that money stock is held constant). Such is the case presently, more or less. (CPI inflation remains tame and in the midst of extreme weakness in leveraged gold and silver futures prices, physical bullion supplies have become very tight, trading at significant premiums over levered spot prices and with extended delivery periods.)

As we have seen, assets targeted for purchase, such as US Treasuries and MBS, experience price adjustments first. The follow-on flows have been yield-chasing in nature, dropping financing rates and further boosting home and equity prices. This is the short term counter-trend to the fundamental forces of our postulation above. QE directly removes duration risk from the market, and unwind it would add such risk. If aggressive QE were to cease, there would be a sharp drop in bond, equity and home prices.

As Hayek and others have made clear, the initial boost to asset prices spurred by deposit growth will in time be followed by a boost in other components of the GPL, as this deposit money changes hands and gets disaggregated. (In this sense, to hold the TMS constant is a minimum policy objective and expanding it is the preferred objective.) Thus, today’s asset inflation ensures inflation tomorrow of all unlevered components of the GPL (of which physical precious metals and commodities are the prime historic example). Simply, to promote nominal economic expansion in the absence of unreserved credit expansion policy makers must increase the transactional money supply, which in turn increases prices of unlevered assets (e.g., gold) most.

Gold has little functional economic utility today. Those who hold 1) physical gold in possession, 2) allocated physical gold in storage, or 3) physical gold in “nature’s vault” through shares in gold miners, are speculating that there is a growing likelihood that someday gold will either become ubiquitously recognized as cash again or will be used as the basis for fiat currencies (whole or in part) once they are devalued.

The bid for physical gold since 2000 has not been from dedicated financial asset investors in the West. It has been from global producers of human and scarce natural resources, and from global savers seeking to protect their purchasing power from expected and manifest central bank fiat currency dilution. It is seen by them as a store of purchasing power value, not as a speculation. Exchanging fiat currencies for physical gold today is exchanging currency used as media of exchange for the object against which that media is being devalued, and that may someday be more formally devalued by monetary authorities.

Holders view physical gold as the safest form of savings, and see its wild price fluctuations as price fluctuations in the currency in which it is priced – not as fluctuating demand for inert rocks that “don’t do anything” or “aren’t backed by anything.” Yes, a hunk of gold is a no more than a paperweight; just as a pile of US dollars is no more than kindling. What makes the former potentially valuable vis-à-vis the latter is nothing the former does, but rather what central bankers do to the latter.

And the Horse You Rode in On

Analysts show their ignorance when they compare the returns of levered paper gold futures or ETFs to the returns of stocks or bonds. When the levered paper gold price rises 5.5 times over thirteen years, it means the value of the base money in which gold is being priced is losing great value through dilution and that TMS logic and trends suggest great future price inflation. When spot gold futures fall almost 15% in two days, it is ostensibly the market warning that policy makers are in jeopardy of letting the money stock deflate, and by extension letting nominal prices fall and the nominal economy contract.

When strategists dismiss gold because it does not offer income, they too are expressing their ignorance. If we take the time to keep our identities straight, US dollars do not provide income either unless they are lent. If one is foolish enough to lend out allocated physical bullion in today’s environment, we would imagine she could demand a rate of interest that far exceeds any sovereign or credit yield or equity dividend. (Gold lease rates are struck on fractionally or un-reserved paper gold.)

When financial bloggers, journalists or political gadflies posing as Nobel Laureate columnists gush that investors should not lust after gold, we say heed their advice! Investors should get out of their fractionally-reserved paper gold as quickly as they can. They should not participate on the long side in gold futures, ETFs, swap agreements or even unallocated physical. Paper gold claims that are not exchangeable for specific reserves are notional derivatives exchangeable into fiat electronic cash credits whenever exchanges, banks or ETF sponsors determine. The only reason to hold gold in the first place is because some day you may need to possess it. (Perhaps this is precisely what we are experiencing today?) Gold is for savers that trust their calculators, not investors that need to be popular.

Imperial Constraint

Serious economists understand that the perception of gold greatly impacts the ability of monetary authorities to manage the sponsorship of their currencies (e.g., Larry Summers’ early work on Gibson’s Paradox and gold). There are two practical, inter-related forces at work here: 1) since 1971, “money” has been notional, without a fixed basis for valuation, and; 2) the global sponsorship of baseless currencies has relied upon unified agreement among global monetary authorities that the perception of their baseless fiat currencies as a reasonable store of purchasing power value is maintained.

We do not argue with the ease and practicality of the current baseless fiat currency system as exchange media, but we dispute the validity and therefore the sustainable viability of “money,” as it generally perceived today, as a store of purchasing power. This is the point of criticality.

We think declining real economic activity will overcome the best intentions of monetary authorities, banking systems and the political status quo intent on maintaining the current monetary regime. We do not think there will necessarily be a market-based signal:

- FX traders will continue to chase relative financial returns by whacking currency moles (the central bank with the strongest currency in FX terms is next “to ease”)

- Dedicated financial asset investors mandated not to care about real absolute returns will stick with stocks and bonds

- Tame consumer price baskets will continue to fool academic economists and financial media into missing true current inflationary backdrop we all experience at the grocery store as well as the causes of future global price inflation until they have occurred

- Gold bugs will continue to lack popular credibility by seeing state-mandated obedience behind every policy pronouncement (whether or not some may be valid)

But that does not mean change is far off. The realities that define the status quo above are ongoing coincident occurrences within an over-leveraged economy subject to abrupt change. We think the only way to maintain one’s bearings amid the tumult is to focus clinically on fundamentals and try to make reasonable extrapolations in anticipation of ultimate fundamental value reconciliation in the global relative pricing matrix. Consider:

- Prices of goods, services, wages, financial assets, etc. can rise meaningfully while their values to societies more or less remain the same.

- Inflation-adjusted capital and sustainable wealth cannot be built in aggregate until there is wage inflation in excess of credit inflation.

Monetary authorities are methodically de-levering their banking systems through monetary inflation – first through bank reserve creation (now) and next (soon?) through an increase in the transactional money supply. The objective is price inflation that diminishes the burden of debt repayment. (As noted above, the modern banking system is systematically short reserves. The TMS can be expanded either through reserve inflation or bank credit inflation or, of course, some combination of the two which nets positively.)

So we ask again, are there really unpredictable market shocks or are investors not paid to care? To us, all signs are pointing towards the next currency reset. We think monetary authorities are compulsively destroying the current global monetary system; they simply have no choice if they are to keep it afloat in the short term. We further think they will have no choice but to replace it with a gold exchange standard they oversee (i.e., a gold-standard-light, “Bretton Woods” type reset). (Perhaps this explains the current redistribution from unreserved paper gold and to physical gold?) We would not be surprised if, in 2014, someone like Larry Summers or Tim Geithner takes control of the Fed and oversees such an operation.

Investment Implications

From current levels, we speculate the best performing holdings in the environment described above would be: 1) shares in precious metal miners (with high ratios of permitted reserves to market caps), 2) allocated physical gold and silver, and 3) inventoried consumable commodities.

We think equity markets will generally rise, but not enough to produce positive real returns. Operating businesses with inelastic demand and pricing power, such as consumer staples and utilities, should continue to do well. We note they have already performed well in the markets relative to other segments, and so their public equity performance may be somewhat discounted. Nevertheless, in an economic environment characterized by significant inflation they should continue to perform.

We are not impressed generally with “high dividend” paying equities today, given the potential for significant disinvestment among investors when those dividends seem small next to inflation. Further, we are not generally attracted to businesses with deflationary business models, including those in industries in which innovation drives the value (and pricing) of current-state technology lower. Increased earnings through cost savings, the benefit of productivity advances brought by innovation, should pale next to revenue declines from decreasing consumption and capital expenditures. We are generally agnostic towards businesses supported by government policies, including banking, defense and health care.

We think fully integrated producers of consumable commodities, such as crude oil and industrial metals, that have inventory or that control pricing, will ultimately be able to maintain their margins; they should produce positive real returns in a highly inflationary environment. However, they are vulnerable to near-term weakness in business activity, and so we think they could underperform inflation temporarily in a stagflationary environment.

We think the best risk-adjusted returns in the equity markets, by far, will be from precious metal miners with significant accessible reserves. They are asset plays with present values that are overwhelmingly positively convex to bullion prices. Their disappointing past operating results, as they ramped up reserves and production following twenty five years of stasis, have been a valid concern for financial asset investors with near term performance pressures; however, they are now positioned to exploit higher bullion prices. We think fears of future cost increases within an inflationary environment that would detract materially from future earnings are not valid for well-positioned miners. We do not believe future cost increases will rise anywhere near the future value of their reserves (and might even fall within a stagflationary environment).

Further, the extraordinary weakness of precious metal miners over the last two years, both in absolute terms and relative to bullion, suggests very little market sponsorship presently (confirmed further by the industry’s tiny aggregate market cap). This should be reversed suddenly upon the first whiff of inflation. Their exchange-listings provide easy access for dedicated equity investors, and their beneficial tax treatment in most domains over collectibles like physical bullion and bullion ETFs suggest further support. (Disclosure: QB’s largest exposure is precious metal miners.)

Bonds and cash should suffer greatly in a highly inflationary environment, but maybe not in the manner many would think. We think extreme price inflation and a monetary reset would not necessarily trigger higher interest rates or widespread defaults. In fact, we believe a monetary reset would sustain nominal bond pricing. While bonds would be “money good” following a reset, we think their interest and principal would be repaid with bad money, giving them very negative real returns. The purchasing power of fiat cash would decrease in kind as ongoing cash flow needs rise.

Real estate cannot be painted with a broad brush in an inflationary environment. We think the value of most real estate would remain the same, all things equal, although there would be very divergent price performance. Theoretically the value of term-funded income producing property should rise, although we recognize the performance of properties including multi-family and office rentals has already been strong.

The forward-looking problem with real estate in an inflationary environment is that since the advent of securitization in the 1980s it has become a leveraged financial asset. There is not necessarily anything “real” about it anymore because its ongoing value relies on the availability of fiat credit, both for its owner to roll over financing and, for income producing properties, for tenants and customers to be able to afford increased costs. Generally, we expect the real value of most real estate, including housing, to not keep pace with the purchasing power diminution of the currencies in which they are denominated.

Source:

Lee Quaintance & Paul Brodsky

pbrodsky.qbamco.com

Imperial Constraint, April 2013

QBMACO

What's been said:

Discussions found on the web: