@TBPInvictus

It was, I guess, a rude awakening for me when I realized, many years ago, that most of the talking heads I saw on TV had no idea what the hell they were talking about. The sooner one learns that lesson, the better. So, take it from me (and BR, who says the same thing): Figure out who’s on their game and who isn’t; who’s got an agenda and who doesn’t. Stick with those who are consistently good and occasionally great, jettison the money-losers and ideologues. Finance is not the place for one-hit-wonders. (How do you wind up with a small fortune on Wall St? Start with a large one. Or follow the money losers because they deliver a message you want to hear, not one that will make you money.)

Now, to be clear, there’s a difference between being wrong and being ignorant (though some folks are often both). And there’s yet another, more insidious category: those who deny they’ve ever been wrong, gloss over their mistakes, don’t learn from them, or perhaps pretend they never happened. Being wrong is one thing, staying wrong is another; there’s nothing wrong with the former, everything wrong with the latter.

My jaw about hit the floor last year when I caught Niall Ferguson claim that a sudden, large spike in Federal payrolls was stimulus related when it was actually Census related. I’d never held him in particularly high esteem, but that gaffe just cemented my view of him little more than a cue to change channels.

In the past few days, I (sadly) happened to witness more of the same – this time from Meredith Whitney and, separately, Monica Crowley.

Ms. Whitney was on the tube defending and re-writing her call in December 2010 that there was going to be a debacle in the muni bond market. To the best of my knowledge, Ms.Whitney has twisted, distorted, and re-shaped her 60 Minutes comments six ways to Sunday, never being enough of a mensch to acknowledge that she was, indisputably, wrong – an admission for which I’d respect her. Instead, I’ve lost all respect for her inability to come to terms with this one horrific call (notwithstanding whatever else she may have gotten right or (mostly) wrong).

Here was Ms. Whitney with Steve Kroft in December 2010 (emphasis mine):

“There’s not a doubt in my mind that you will see a spate of municipal bond defaults,” Whitney predicted.

Asked how many is a “spate,” Whitney said, “You could see 50 sizeable defaults. Fifty to 100 sizeable defaults. More. This will amount to hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth of defaults.”

Municipal bonds have long been considered to be among the safest investments, bought by small investors saving for retirement, and held in huge numbers by big banks. Even a few defaults could affect the entire market. Right now the big bond rating agencies like Standard & Poor’s and Moody’s, who got everything wrong in the housing collapse, say there’s no cause for concern, but Meredith Whitney doesn’t believe it.

“When individual investors look to people that are supposed to know better, they’re patted on the head and told, ‘It’s not something you need to worry about.’ It’ll be something to worry about within the next 12 months,” she said.

I respect the fact that Whitney went out on a limb and made a bold call. I really do. As she makes the rounds to peddle her new book, she should own up to the fact that her call was dead wrong instead of trying to re-write and distort what she plainly said.

No, the Reagan recovery did NOT produce 1.1 million jobs in one month

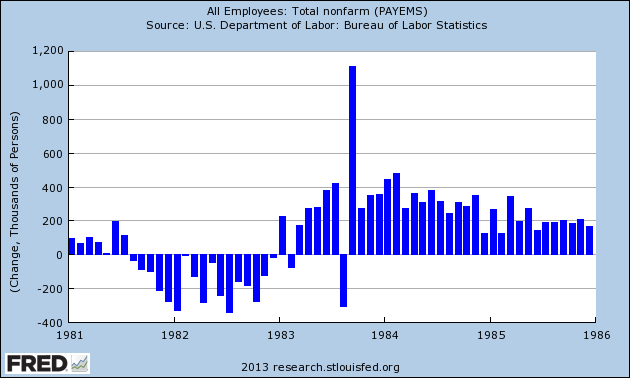

Which leaves Monica Crowley who, while dumping on Friday’s jobs report (1:07) invoked…wait for it…the Reagan recovery and the “fact” (not really a “fact”) that “…we had one month in the Reagan recovery, 1.1 million new jobs created in a single month…”. It’s possible, of course, that Crowley got her misinformation from National Review, which was apparently peddling that line a couple of years ago. Sadly, the former paper of record for Wall St. – the Wall St. Journal – also had no problem lying about the 1983 report, and that may well have been the point of origin:

As it happens, the biggest one-month jobs gain in American history was at exactly this juncture of the Reagan Presidency, after another deep recession. In September 1983, coming out of the 1981-82 downturn, American employers added 1.1 million workers to their payrolls, the acceleration point for a seven-year expansion that created some 17 million new jobs.

And so a talking point – having no basis in fact – is born, and continues to make the rounds.

Of course, not recognizing that number, it was off to the BLS archives for me, to find out what was going on. I suspected I had an inkling, and my hunch proved spot-on.

As BLS originally reported (so no revisions here; emphasis mine):

Nonagricultural payroll employment rose by 735,000 in September to 90.5 million, seasonally adjusted. About 675,000 of this increase, however, represented the return of employees to payrolls following settlement of strikes, chiefly that of communications workers. [Ed note: Without doing the requisite digging, I’ll assume future revisions eventually took the number to >1MM.]

Here’s what that period in time looked like, and what Ms. Crowley was referring to (note the precipitous decline in the month prior to the spike up – that’s the workers being laid off the payrolls):

BLS, prior month:

The number of employees on nonagrlcultural payrolls fell by 410,000 in August to 89.8 million, seasonally adjusted. However, the establishment survey data were significantly affected by a nationwide strike of some 700,000 communications workers.

The point here being that during this period we were generally printing between 200k – 400k nonfarm payroll jobs per month, which is certainly admirable enough. Ms. Crowley could have said as much and been done with it instead of pushing a bogus 1.1MM number. So, either she was unaware of the circumstances surrounding that anomalous print, or chose to forge on ahead with information she knew to be misleading – neither scenario reflects well – for Ms. Crowley, National Review, or the Journal. So let’s put this one to bed, shall we?

Update (June 10): Replaced the line graph with a bar graph, a more appropriate choice under the circumstances.

What's been said:

Discussions found on the web: