Its Friday, after what was for me a long and annoying 17 days. But the shutdown is over, US markets are at all time highs, and Bob Shiller got his Nobel (more on this tomorrow).

You might think that I would be at peace with the current state of the world, but life is never that simple. You see, I have assumed the task of explaining things which require explaining. By some quirk of fate and an odd academic background, I find myself with skills in simplifying complex matters. Whether OCD or over-compensation for some other defect, this is my lot in life. (I made peace with it long ago).

As we discussed yesterday, amongst all of the background nonsense since October 1, the noise about the deficits was not really about budget deficits at all. Rather, it was about a decidedly narrow ideology held by a small percentage of Americans. Their belief is that government should be much smaller. This is a legitimate political ideology, one that has persisted over the centuries.

Their approach to this philosophy, however, is far less intellectually honest. Rather than having a full on debate on that subject — a debate they are likely to lose — they have chosen a very different approach. This time around, they made the deficit a proxy.

Because of what I do for a living, I found this offensive. Deficits impact fixed income, an important part of portfolio planning. They impact available credit, capital for investment, in a broad and varied way. Hence, the deficit is a genuine issue, a real problem that should be addressed in a mature and responsible way. It can be easily solved using intelligent solutions, but for the ideologues in Washington DC (and elsewhere) who refuse to treat it as the basic mathematics and accounting problem it actually is. The way the Tea Party and others have treated the deficit reminds me of the approach Meredith Whitney took to Municipal Debt. Both groups are stunningly ignorant about their subjects, while possessing the skills to allow them to exploit the topic, hog the spotlight for themselves and other tangential pet issues.

The Tea Party, like Whitney, turned an important question of debt and credit and solvency into one giant PR clusterfuck.

Back to our issue of taxes (next week, I will address spending). Amongst Industrialized Nations, the United States has amongst the lowest tax rates in the world, especially for those folks (like myself) who reside at the top of the income scale.

To demonstrate this, I want to point to the IMF’s World Economic and Financial Surveys: Taxing Times. It is chock full f great charts and data and other interesting results of the IMF survey.

The two below caught my eye. They are rather instructive for our discussion of taxes and deficits in the US.

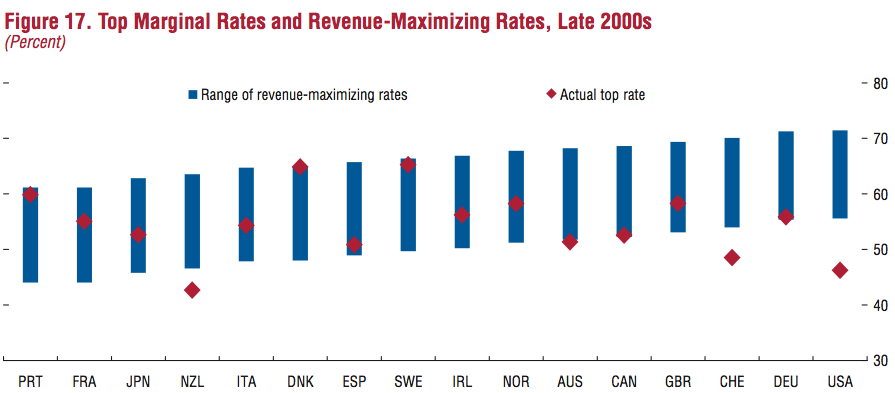

The first looks at major industrial nations, and compares what the IMF calls their Revenue-Maximizing Tax Rates (blue line) versus their actual top rate (red dot).

As you can see, some countries — Denmark and Sweden — are at the top of the revenue maximizing ranges. Other countries — Canada and Germany — are at the bottom of their revenue maximizing ranges.

Then there is the United States, which is simply far off the scale, way below the bottom of its revenue maximizing range.

If your concern is deficits, than you must take notice of how much money the USA is leaving on the table. I am not suggesting that the role of government should be to maximize their tax revenues, but rather to suggest that if you want to close the deficit, you need to at least be in a defendable range. The US is not.

click for ginormous charts

Source: IMF

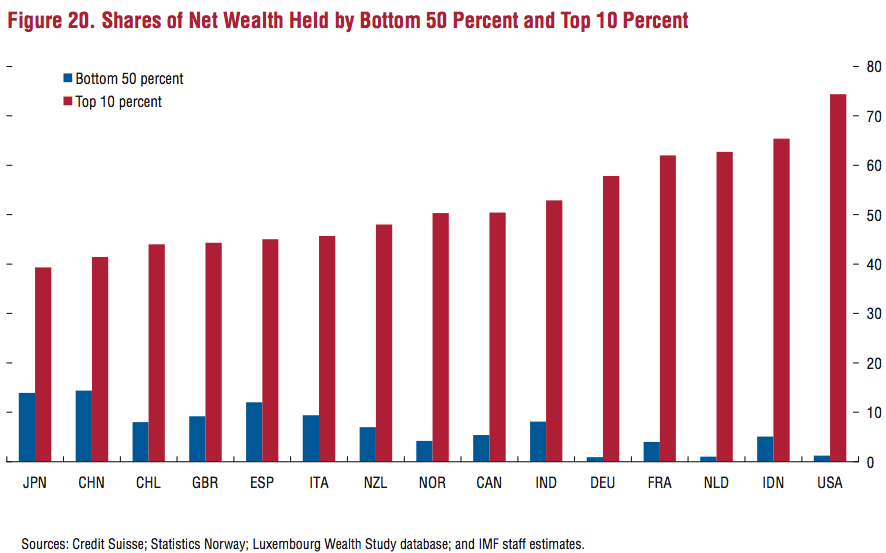

Not coincidentally, when we look at shares of Net Wealth held by the bottom 50% of he population versus the top 10%, the United States is off the scale. We are the most unequal nation in the world.

Source: IMF

The inescapable conclusion presented to us by this data is that our tax policy is responsible for both the world’s greatest inequality among developed nations, and our ongoing deficits.

If you have a better explanation for our current conditions, or the net results of our tax policies, I would love to hear it.

Source:

Fiscal Monitor Taxing Times

World Economic and Financial Surveys

IMF October 2013

http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fm/2013/02/fmindex.htm

What's been said:

Discussions found on the web: