Defense! Google’s Nest Labs acquisition is a smart move

Barry Ritholtz

Washington Post, January 26 2014

With the Super Bowl just a week away, the age-old question of whether offense or defense wins big games is at hand. “The best defense is a good offense,” goes the saying, with the Denver Broncos called the best offensive team ever. The Seattle Seahawks are no slouches either, with their top-ranked defense and an explosive offense.

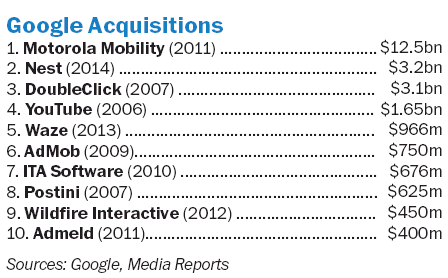

The question of offense or defense has been on my mind since Google acquired Nest Labs for the eye-popping sum of $3.2 billion.

If you look at this purchase solely from the perspective of an investor, it seems quite pricey. After all, this is a relatively new start-up with modest revenue in a niche market of thermostats and smoke detectors. From the perspective of those deploying capital in the expectation of a return on investment, future gains are likely to be paltry relative to the billions invested.

But if you consider this from the perspective of a technology company horrified at the prospect of becoming irrelevant, the acquisition looks very different. Rather than look at the costs of making an acquisition like this, consider the risk of failing to aggressively play defense. History is replete with examples of tech firms that were marginalized by new companies and technologies.

Indeed, some of the biggest strategic errors have occurred in the past decade alone. The companies that ignored specific risks from the latest innovations came to rue that decision. Think BlackBerry circa 2007 — it hardly thought of Apple’s newfangled touchscreen iPhone as a threat to its core business. Yet BlackBerry’s global market share collapsed from nearly half of all smartphones sold in 2009 to less than 3 percent today.

Microsoft offers a similar cautionary tale. A monopoly market share combined with an arrogant CEO — Steve Ballmer refused to let his kids have an iPod or use Google — left the software giant blindsided by threats to the core business. Indeed, hubris led the makers of the world’s dominant operating system to miss or ignore many tech developments: social networking, search, cloud computing, smartphones, tablets, MP3 players, user-generated content, blogging, microblogging (Twitter) and location-aware apps. But it was Apple’s iPad (along with other tablets such as those using Android) that became the biggest threat to their basic Windows laptop/desktop PC business.

Perhaps the granddaddy of cautionary technology tales is Eastman Kodak. The film and camera manufacturer was so dominant that, according to a case study by Harvard Business School, in 1976 “Kodak controlled 90 percent of the film market and 85 percent of camera sales in the United States.” Astoundingly, it was Kodak itself that developed the digital camera in 1975. Fearing that digital photography would cannibalize its photographic film business, the company buried its own invention. That helped sales for the next decade or two, but, eventually, digital cameras came to dominate photography. Rather than own the future, they clung to the market share of the past. It should surprise no one that Kodak eventually filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection.

None of this has been lost on the founders of Google, with their dominant position in search. Their acquisitions and research and development actions suggest that they are cognizant of how easy it is for a company to lose its grip on its primary market. This is especially true for dominant firms that became complacent — like Kodak, Microsoft and BlackBerry did.

I credit Google for having the foresight to identify threats to its main business of selling advertising against search results. The potential loss of market share in the mobile space led them to the Android acquisition. That gave Google a solid footprint in mobile, preventing it from having to play catchup like BlackBerry and Microsoft did. Lower-priced Android phones now have a dominant market share (and Android tablets have a respectable share) — even though neither is especially profitable versus Apple’s iPhone. However, they ensure that Google’s core search business has a large and growing footprint in the mobile space.

One can only imagine the conversations occurring in Mountain View today had Google not made that Android purchase. Might the Nest Labs acquisition look like a similar no-brainer years hence? It has the potential to be, if not quite as large as Android, then perhaps nearly as important.

Most of Google’s home technologies have failed to catch on in a major way. The Android@Home platform didn’t, and the Nexus Q streaming media device has not set the world on fire. Don’t even ask about Chromecast Dongle (whatever that is).

While Google’s internal R&D has not created the next YouTube (Google Plus, anyone?), it has put together a very good track record of acquisitions that enhance its core business. YouTube has grown into a huge winner, giving Google a dominant position in online video. Variety reported that the video division grossed $5.6 billion in ad revenue in 2013. (Google’s stock price increase after the announcement of the YouTube deal paid for the $1.65 billion purchase). Motorola Mobility — another pricey purchase at $12 billion — as a clever patent acquisition; it has mostly insulated Google from countless mobile patent infringement lawsuits against Android.

Meanwhile, the Wall Street Journal reports that Nest Labs is selling 100,000 smart thermostats a month — a respectable number for a start-up.

Yes, $3.2 billion is certainly a lot of money to you or me, but it’s barely 5 percent of Google’s cash. It’s a pittance relative to its $388.8 billion dollar market cap. The risk to Google is not the cost of acquisitions such as these, but the risk to its core business down the road of failing to do so. If the “connected home” is a thing a few years hence, what new or existing company might be doing to Google what Apple did to BlackBerry?

When big tech-driven firms make acquisitions of this sort, they are doing so for very different purposes than investors do. They are acquiring engineering talent. They shave off years of research and development with a known outcome, rather than a who-knows-what outcome years down the road.

Google’s founders have had a good eye for imagining what technologies will be significant in the near future. No one asked Google to develop self-driving cars, but it helped them with street views for Google Maps. Nor was there a clamor for an alternative platform for mobile, but they turned this into a tremendous asset and created competition in the space. The same can be said of purchases in e-mail security or local advertising or even robotics.

Might Google be wrong that the connected home is the next new thing? Certainly. Perhaps nothing of great value will develop from this purchase. But if Larry Page and Sergey Brin believe this could be a significant technology, then it is a small price for Google to pay to ensure it participates in the integrated-smart-home market.

If not, what’s $3 billion to a $390 billion company sitting on $55 billion generating $5 billion per quarter in free cash flow? Consider it a small insurance payment.

~~~

Ritholtz is chief investment officer of Ritholtz Wealth Management. He is the author of “Bailout Nation” and runs a finance blog, the Big Picture. Twitter: @Ritholtz.

What's been said:

Discussions found on the web: