After Amazon.com missed analysts’ quarterly profit forecasts Thursday, investors lopped as much as 10 percent off of its stock price, the most in a year. The company reported fourth-quarter net income that more than doubled to a record $482 million from a year earlier; revenue rose an astonishing 22 percent to $35.7 billion. Revenue in cloud services sales soared 69 percent to $2.4 billion.

These are terrific numbers, but as we see so often, it is the expectations that matter.

But let’s back up a bit, to 2014’s fourth quarter, when Amazon surprised investors by reporting a profit. I can’t believe I am about to type these words, but with the benefit of hindsight the company might have been better off reporting a loss then.

It helps if we understand that Amazon Chief Executive Officer Jeff Bezos has spent more than two decades reinvesting earnings back into the company. That steadfast refusal to strive for profitability never seemed to hurt the company or its stock price, and Amazon’s market value (now about $275 billion) passed Wal-Mart’s last year. All the cash it generated went into infrastructure development, logistics and technology; it experimented with new products and services, entered new markets, tried out new retail segments, all while capturing a sizable share of the market for e-commerce.

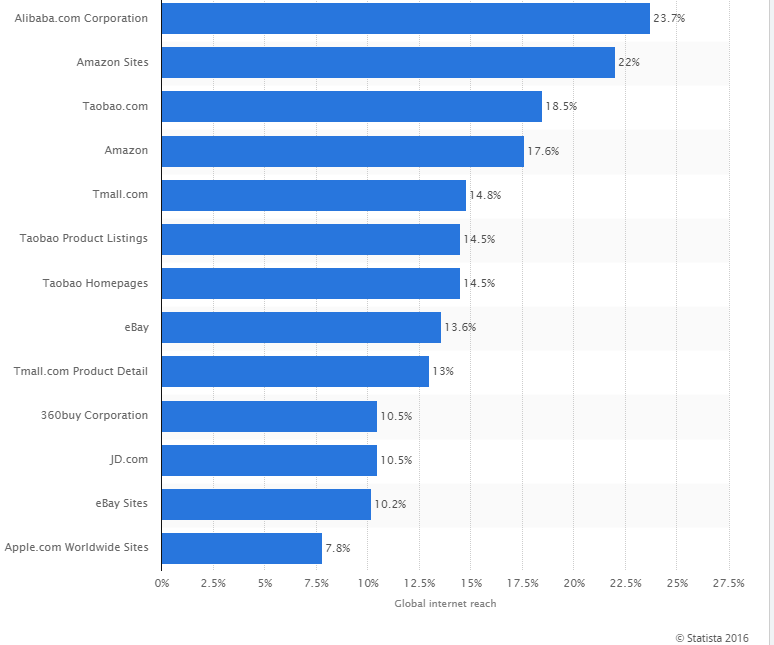

How large a share? Overall, Amazon commands 22 percent of online sales. But it’s even more dominant than that data point suggests:Bloomberg reported that Amazon took in 39.3 percent of e-commerce spending from Nov. 1 through Dec. 6; on Cyber Monday, Amazon captured almost 36 percent of all online sales. Those are strong numbers, but the really eye-popping stuff was mentioned in a note from Macquarie Research: it estimates “that for every $1 of e-commerce growth, Amazon will take 51 cents.”

These are, in Trumpian terms, huge numbers.

Source: Statista

But here, it seems, is the source of the disappointment: That surprise profit back in 2014’s fourth quarter seemed to attract new investors who may have assumed that the company was moving into a new more mature — and profitable — phase. That helped drive its share price up 118 percent in 2015, making Amazon the second-best performer in the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index.

Those investors were wrong. They were betting on a profit juggernaut; they got something entirely different.

So here’s how to think about Amazon. It was and remains a giant retail lab experiment. Bezos has no fear of failure, a quality that burdens so many business leaders.

And so far, at least, Amazon’s winners far outweigh its failures. Amazon’s successes such as the Kindle, Amazon Prime, same-day delivery, video streaming and cloud services are all the result of not being reluctant to go for big, bold initiatives. A lesser company and a lesser CEO might shun such experimentation.

But did Amazon pretend to be a normal company, one to be judged by its earnings gains? I don’t believe this was a bait and switch. It has a stockpile of almost $16 billion in cash and equivalents and lots of accounting flexibility when it comes to deciding how profitable it wants to be. The quarters when Amazon is profitable may just be another experiment.

Perhaps this kind of experimentation has a downside. If naive investors thought they were getting in on Amazon’s transition to its profitable stage, they probably are disappointed. But should we feel sorry for them?

As of 2015, traditional brick and mortar stores generated more than 90 percent of the $5 trillion in U.S. retail sales. E-commerce has grown for more than two decades, yet it claims less than 10 percent of the total. There is every reason to expect that the sector will take an ever-larger piece of the market.

The issue has never been how much market share will Amazon capture. We know it will be a lot. For Amazon investors, the more crucial question is how much patience do you have?

The answer tells you whether you should buy or sell Amazon shares.

Origianlly published as: How to Know If You Should Buy or Sell Amazon