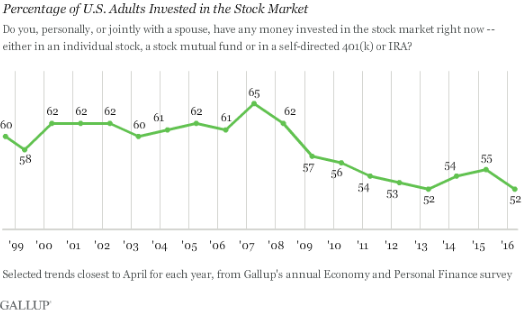

Before the Great Recession, almost two-thirds of Americans owned stocks. That number has since fallen to a little more than half, as you can see from the chart below:

This is an important development with ramifications for retirement planning, demographics and income inequality.

First, a little history: Since late in the last century, one of the defining developments of equity markets has been how new technology and competition democratized investing. We can trace this back even further, to May 1, 1975, when the brokerage industry had to stop charging fixed commissions and start competing on the basis of price.

Trading, research and market commentary moved online in the 1990s. Soon after, a large part of the adult population came to believe that: a) they should be in the market; b) they had the skills to pick stocks and/or time markets; c) everyone was going to get rich. Recall the Discover brokerage commercial in which a tow-truck driver, who by implication had struck it rich in the market, owned an island-nation? In 60 seconds the ad captured all the giddiness and naivete of that era.

Call it the revenge of the Dunning-Kruger effect — that the least competent are the most certain of their skills. Reality long ago intruded on all that false confidence: The dot-com collapse, the housing boom and bust, the commodities rise and fall, the Great Recession, and then to add insult to injury, a tripling of equities since the March 2009 lows. These events have disabused most amateurs of their belief in their investing prowess. Is the rise of indexing and passive investing any surprise?

Just as many former renters briefly became homeowners during the housing boom, only to return to renter status, so too did many stock-market dabblers take what was left of their capital and go home. Sure, more than half of American households still own equities, but for most of those investors it’s a modest amount (and the other half owns precisely zero); about two-thirds of equity ownership is held in the top 5 percent of portfolios. The top 20 percent owns 85 percent of all financial assets, according to the Levy Institute; the Economic Policy Institute is even more specific at 87.2 percent. Income gains have been even more skewed toward the top.

The social ramifications of this are profound, though the implications for financial markets are more nebulous. For the most part, equity ownership has always been concentrated among the wealthy. Will increasing ownership concentration have an effect on markets? It might, though it isn’t clear how.

However, there are good reasons to be concerned about the decrease in market-participation rates:

- The decline of equity ownership reflects a failure by too many Americans to save, which portends untold trouble amid the looming retirement of the baby boom generation.

- Income inequality is a burgeoning issue in the U.S. (and globally). Declining rates of stock ownership are a possible sign that the chasm is widening; this might increase the possibility of social and political upheaval.

- Politics and policy are being broadly influenced by a middle classthat sees itself falling behind and unable to catch up. Look no further than the present presidential elections for manifestations.

There is a corollary issue — stocks are primarily owned by people who tend to be wealthier, male and white. This is a topic worthy of another column entirely.

In the meantime, falling equity ownership may well point to very big problems down the road.

Originally: The Thrill Is Gone From Owning Stocks