Negative Interest Rates: A Tax in Sheep’s Clothing

Christopher J. Waller, Director of Research, St. Louis Fed

On the Economy, May 02, 2016

If you pick up any principles of economics textbook, there will typically be a discussion of taxes and tax incidence. Tax incidence describes who bears the burden of a tax. For example, suppose the government levies a payroll tax on a firm. The burden of the tax may be borne by the firm, the workers or the firm’s customers.

How can this be if the firm is responsible for paying the tax? The firm may bear the burden of the tax by accepting lower after-tax profits. However, the firm can pass the tax onto its workers by paying them lower wages or hiring fewer workers. The firm can also pass the tax onto its customers by charging them a higher price for the firm’s output. In general, all parties bear some portion of the tax.

Similarities to Taxes on Banks

This logic also applies to a tax levied on banks. Banks hire inputs (in this case, deposits), which are used to produce output (loans). The bank charges a price for its output (the interest rate on the loan) and pays wages to its inputs (the interest rate on deposits).

The spread between the loan rate and the deposit rate determines the profit margin for the firm on a loan (ignoring default costs and other costs for ease of exposition). So any tax imposed on banks will be borne by the bank, the depositors and/or the borrowers. The firm can bear the burden of the tax by accepting lower profits. However, the bank can also pass the tax onto depositors by paying a lower interest rate on deposits and/or pass the tax onto borrowers by charging them a higher interest rate on loans.

Negative Interest Rates

This brings us to negative interest rates. Many foreign central banks—such as the European Central Bank, the Bank of Japan and the Swiss National Bank—have implemented negative interest rates on bank reserves as a policy tool to stimulate demand for goods and services. If a bank holds a dollar of reserves, the central bank may take, say, half a cent.

The hope is that a negative interest rate will induce firms to lend out the reserves by charging a lower interest rate on loans. In short, “use it or lose it.” More lending would stimulate spending on goods and services, which would lead to higher output and upward pressure on inflation.

A Tax on Reserves

But a negative interest rate is just a tax on the banks’ reserves. The tax has to be borne by someone:

- The banks can choose not to pass it on and just have lower after-tax profits. This will depress the share price of banks and weaken their balance sheets by having lower equity values.

- The banks can pass the tax onto depositors by paying a lower interest rate on deposits or charging them fees for holding the deposits. In either case, depositors have less income to spend on goods and services.

- The bank can pass the tax onto borrowers by charging them a higher interest rate on a loan or higher fees for processing the loan. In either case, it is more costly to finance purchases of goods and services by borrowing.

None of this sounds very “stimulative” for consumer spending. But then, no tax ever is.

Negative Interest Rates in Other Countries

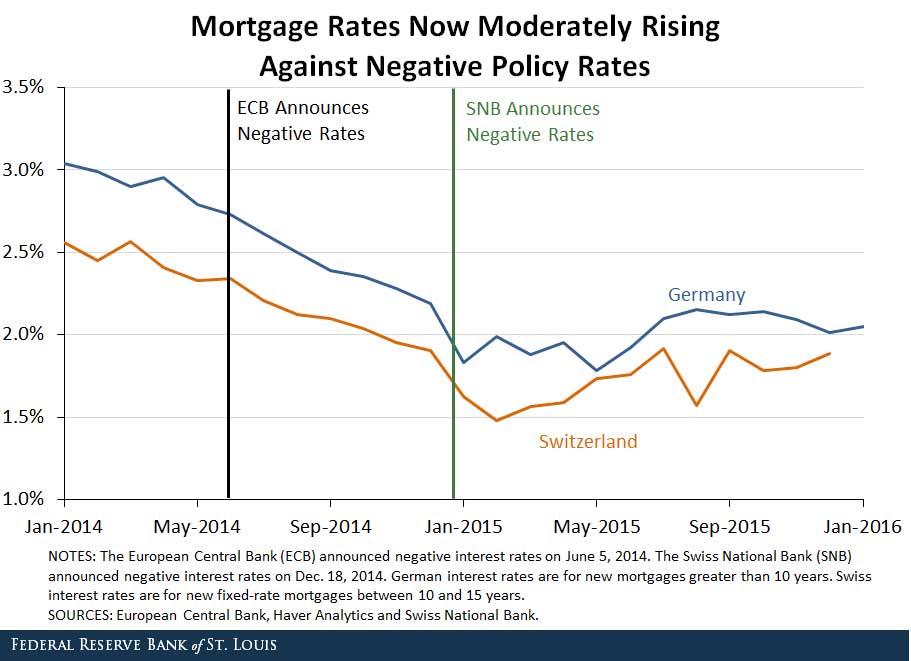

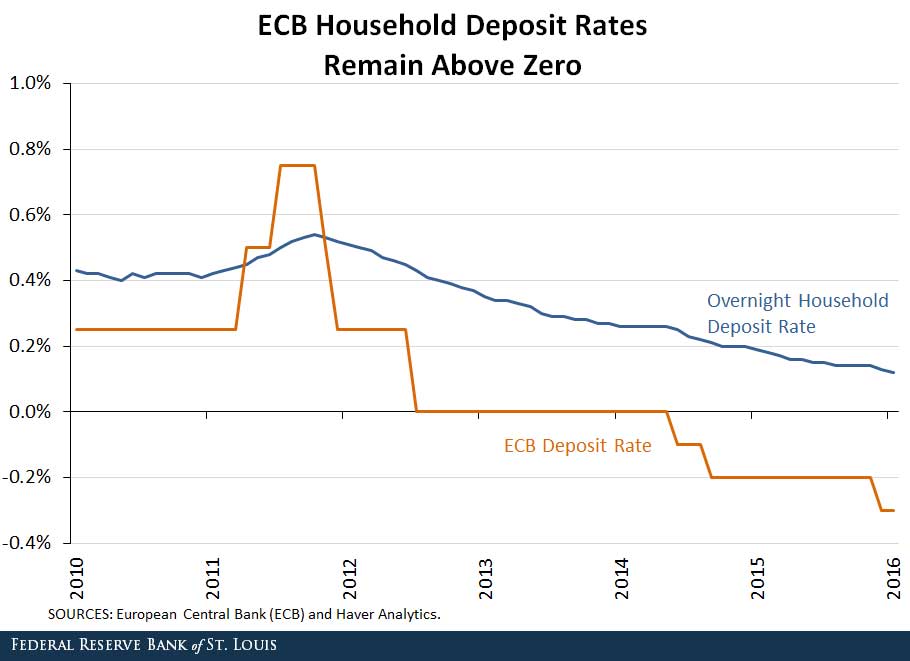

What has happened so far in countries that have tried negative interest rates? The figures below provide answers. As seen in the first chart, bank stock prices have definitely taken a hit. After initially continuing their downward trends, interest rates on mortgages have now risen in Germany and Switzerland (the second chart). Banks have been very reluctant to charge negative deposit rates for fear of a backlash from customers (the third chart).

At the end of the day, negative interest rates are taxes in sheep’s clothing. Few economists would ever claim that raising taxes on households will stimulate spending. So why would they think negative interest rates will?

Additional Resources

- On the Economy: Projecting Real GDP Growth for the Next Decade

- On the Economy: How Has the Current Account of the U.S. Changed?

- On the Economy: Better Measure of Output: GDP or GDI?

What's been said:

Discussions found on the web: