Most investors are (or at least should be) familiar with the concept of “Home Country Bias” — the natural tendency to be more familiar and comfortable with public companies in your home country.

Investors everywhere consistently display this trait, which is in direct conflict with the basic principles of international diversification.

A 2014 report by Vanguard found that “Equities not domiciled in the United States accounted for 51 percent of the global equity market as of Dec. 31, 2013.” U.S. equities accounted for the rest. Despite the size of non-U.S. markets, U.S. mutual funds engaged in classic home country bias, holding “only 27 percent of their total equity allocation in non-U.S.-domiciled assets.”

In other words, investors were about 50 percent underweight when it came to equities outside their country. This bias increases the risk and volatility of portfolios, and is a drag on performance.

In the U.S., the impact is partially muted, given the dominant size of U.S. equity capitalization (49 percent) relative to the rest of the world. Nonetheless, the Vanguard study shows that U.S. investors’s holdings of U.S. stocks significantly exceeded the country’s share of the global market.

Now consider the typical domestic portfolio in Canada, which accounts for 4 percent of global equity capitalization. According to a recent survey from the International Monetary Fund, Canadian investors allocate a mere 40 percent of their total equity investments outside Canada. Their local allocation to Canada is about 10 times what it should be. The numbers are similar for the U.K. The considerably smaller size of these markets means that these home country biases create a significant over-exposure to home country companies. Radically reduced diversification is the net result.

The local economy affects not only an investor’s portfolio, but their employment and incomes. Hence, there is significant risk tied to the performance of the local economy. The obvious solution is a more global allocation that is closer in relative proportion to global market capitalizations.

And there is another bias that comes into play. For those of us in the U.S., there is an apparent regional and state preference. The part of the nation where you reside will influence your portfolio holdings in subtle but significant ways.

That is the finding of OpenFolio, a site that allows investors to see how their portfolios compare to those of other people on the site.

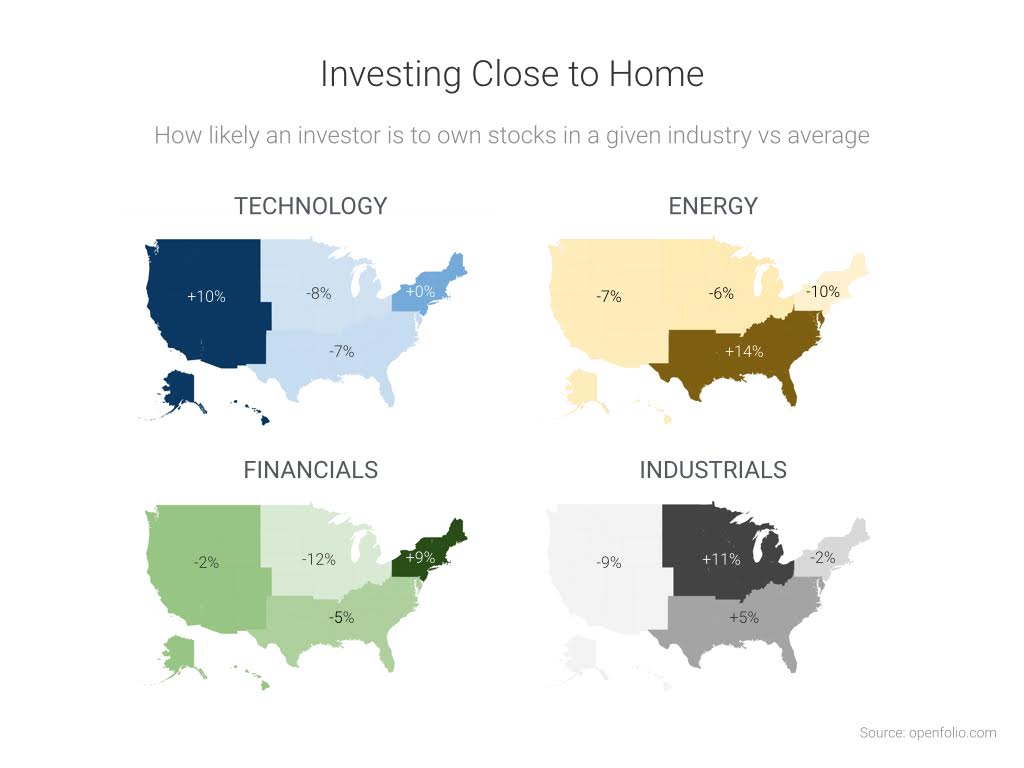

Take a look at the map below. It shows how the regional bias manifests itself relative to your area in the U.S. If we break the nation into four areas — North, South, East and West — we can identify a variation of home country bias, aligned to the dominant industry within each region.

Source: Open Folio

If you live on the West Coast, near the technology hubs of Silicon Valley, you are very likely to be overweighted in technology by 9.5 percent or so. Live in the Northeast, and you are overexposed to finance by 9 percent. Investors in the industrial Midwest are likely to have 11.8 percent more industrial companies in their portfolio than the rest of the country. The greatest overexposure is in the South, where energy holdings are 13.7 percent above the average.

Some of this overweight might be due to employee stock option plans. After all, Google’s founders, and most of its employees, live in or around Mountain View, California. Their portfolios are likely to be filled with Google shares and/or options. The same is true for JPMorgan and Goldman Sachs in New York and Boston, Exxon Mobil in Texas, and 3M in Minnesota. Without access to the full data, there’s no way of telling.

Still, some of this variation could be due to a regional version of home country bias. The odds are that even nonemployees know people who work in the dominant industries in their areas. Is it possible to live in San Francisco and not know tech workers? Can anyone in New York not know people who work in finance?

What matters most to investors is at least having some awareness of the factors that may be biasing their behavior. That insight gives them a fighting chance to prevent irrelevant considerations from shaping their portfolios

Originally published as: Your Local Investing Bias Could Cost You

Which raises the question of how relevant is domicile these days, especially for US companies?

Very enlightening, Barry! Thanks for sharing.

A couple of complimentary perspectives:

1) Could some of the regional bias be connected to trend-following and momentum-based investing? If so, is that a bad thing? Well, besides concentrating risk…

2) Could fees (vis-a-vis mutual funds and ETF’s) be a contributing factor? Virtually every fund I’ve encountered charges significantly higher basis points than comparable U.S.-invested funds. If so, how does one achieve optimal weighting between the cost of owning funds vs. the diversification benefits?

3) Doesn’t owning a broad-based fund such as Vanguard’s Institutional Fund (VIIIX), which is invested in shares from a substantial number of multinational (and/or global) corporations provide exposure to international markets? For example, if 10 percent of my portfolio were invested in the VIIIX, wouldn’t 10-20 percent of that fund provide foreign-based market exposure?

I know it’ll never be a true substitute for a wholly foreign fund, but owning VIIIX costs .02 bps, versus owning Vanguard FTSE All-World ex-US (VEU) @ .14 bps — which admittedly is pretty cheap for an international fund.

One other comment re: OpenFolio. Sounds interesting, will check it out. But there’s no way in Hades that I’m connecting my financial life to social media accounts.

I don’t know how many people are aware of this, but one of the data mining activities already being employed at FB is assessing one’s credit-worthiness via the credit ratings of persons in your social network.

Think about that for a moment: the more diverse your social circle (consider the statistical proportions of the 1% vs. the 99%), the greater the likelihood your credit-worthiness will be negatively assessed.