Forward Markets: Macro Strategy Review

Macro Factors and Their Impact on Monetary Policy,

The Economy and Financial Markets

Summary

In recent weeks, the European Central Bank (ECB), Federal Reserve and Bank of Japan have announced plans to expand their balance sheets through purchases of debt in various markets. Each central bank is fighting the same war with a shared goal: strengthening economic growth to prevent a deep global slowdown/recession that could lead to a debt-deflationary spiral. History suggests that post-credit bubble battles with deflation are especially daunting, with deflation dominating. Since 2010, coordinated responses by central banks whenever deflation has appeared to be gaining traction, has resulted in an ebb and flow in the financial markets, which we expect to continue. However, if central bank programs fail to engender sustainable economic expansions in the U.S., Europe, Britain and Japan by mid-2013, then equity markets will be mispriced and potentially very vulnerable. With global growth slowing, any rise in protectionism, either in the form of currency devaluation, tariffs on imports or trade barriers, would only serve to slow global growth further. We expect protectionism to increase during the next two years.

Fiscal Cliff or Fiscal Grand Canyon?

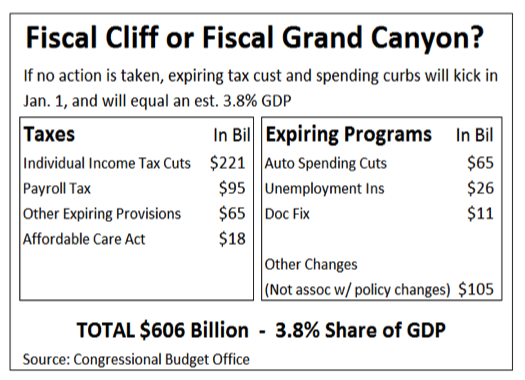

Much attention has been focused on the looming tax increases and federal spending cuts that are due to hit next January. Estimates vary on the total impact on GDP. But a range of 3.5 to 4.6% seems reasonable. In the second quarter, GDP grew 1.7%, so the full impact of the tax increases and spending cuts would likely cause the U.S. economy to flirt with recession in 2013. According to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), if all the tax increases and spending cuts go through, GDP could contract by 1.3% in the first half of next year, with growth of 2.3% in the second half. For all of 2013, GDP would grow 0.5%. Based on their mid-point assessment, the CBO estimates 2 million jobs would be lost in 2013, and the unemployment rate would climb to 9.1% by year-end. As we will later discuss in more detail, we think the CBO’s analysis played a significant role in the Federal Reserve’s decision to launch the third round of quantitative easing (QE3) now, specifically targeting unemployment, and to continue QE3 until the desired improvement in the labor market is achieved. Underlying the Fed’s decision is that the contraction in fiscal policy will be a drag on GDP in 2013. However, the unknown is how much of a drag, which has only increased the level of uncertainty. That in itself is an impediment to economic growth.

Much attention has been focused on the looming tax increases and federal spending cuts that are due to hit next January. Estimates vary on the total impact on GDP. But a range of 3.5 to 4.6% seems reasonable. In the second quarter, GDP grew 1.7%, so the full impact of the tax increases and spending cuts would likely cause the U.S. economy to flirt with recession in 2013. According to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), if all the tax increases and spending cuts go through, GDP could contract by 1.3% in the first half of next year, with growth of 2.3% in the second half. For all of 2013, GDP would grow 0.5%. Based on their mid-point assessment, the CBO estimates 2 million jobs would be lost in 2013, and the unemployment rate would climb to 9.1% by year-end. As we will later discuss in more detail, we think the CBO’s analysis played a significant role in the Federal Reserve’s decision to launch the third round of quantitative easing (QE3) now, specifically targeting unemployment, and to continue QE3 until the desired improvement in the labor market is achieved. Underlying the Fed’s decision is that the contraction in fiscal policy will be a drag on GDP in 2013. However, the unknown is how much of a drag, which has only increased the level of uncertainty. That in itself is an impediment to economic growth.

The odds of the entire enchilada being allowed to take hold are extremely low. That isn’t as bold of a statement as it may sound. After all, we are dealing with Congress, and Congress has rarely confronted a tough decision it didn’t decide to postpone or only partially address. However, the issue of government promises that cannot possibly be fully funded is the elephant in the Capitol that neither party can ignore any longer. This issue will dominate political discussion for the next three to five years at a minimum. And, ultimately, how we as a nation choose to close the gap between funding and promises made will reflect our true character.

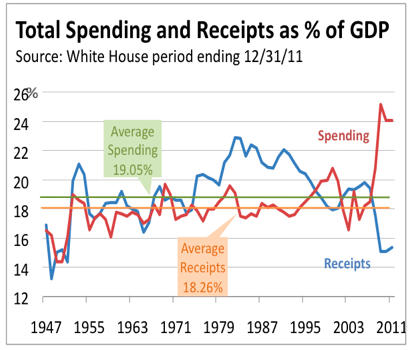

Between 1947 and 2011, Federal government spending averaged 19.05% of GDP, while tax receipts averaged 18.26%. Our economy experienced significant changes during this 64-year period. Both inflation and interest rates soared from low levels in the early 1950s, to coincident peaks in 1981, only to fall again. There were 10 recessions, ranging from shallow and short to pronounced and extended. Politically, both parties at times controlled the White House, majorities in Congress, and briefly both the White House and Congress. The top marginal income tax rate reached a high in 1953 of 92%, and a low of 28% between 1988 and 1990. And this 64-year stretch was marked by the Korean, Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan wars, as well as the Cold War and extended periods of peace. Despite all of these changes, which seem to matter so much, the level of federal spending and tax receipts remained remarkably stable, with the exception of brief fluctuations above and below the averages. To us, this consistency over six decades amid such diverse circumstances, suggests that spending of 19.05% of GDP and tax receipts of 18.26% represent a natural equilibrium.

Between 1947 and 2011, Federal government spending averaged 19.05% of GDP, while tax receipts averaged 18.26%. Our economy experienced significant changes during this 64-year period. Both inflation and interest rates soared from low levels in the early 1950s, to coincident peaks in 1981, only to fall again. There were 10 recessions, ranging from shallow and short to pronounced and extended. Politically, both parties at times controlled the White House, majorities in Congress, and briefly both the White House and Congress. The top marginal income tax rate reached a high in 1953 of 92%, and a low of 28% between 1988 and 1990. And this 64-year stretch was marked by the Korean, Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan wars, as well as the Cold War and extended periods of peace. Despite all of these changes, which seem to matter so much, the level of federal spending and tax receipts remained remarkably stable, with the exception of brief fluctuations above and below the averages. To us, this consistency over six decades amid such diverse circumstances, suggests that spending of 19.05% of GDP and tax receipts of 18.26% represent a natural equilibrium.

The enacted budget for this year calls for spending of $3.796 trillion, or 24.8% of this year’s $15.3 trillion in GDP. Tax receipts are projected at $2.469 trillion, or 16.1% of GDP. The short fall between spending and receipts is estimated at $1.327 trillion. This represents 34% of the $3.796 trillion in spending, and means we are borrowing 34% of this year’s budget. With spending near 24.8% of GDP and receipts just 16.1%, the gap is 8.7% of GDP. Compared to the 64-year average of 0.79% (spending 19.05%, receipts 18.26%), this seems more like a “fiscal grand canyon” than a cliff. Building a bridge over our fiscal grand canyon will take years and a high degree of compromise. Unfortunately, one party refuses to consider tax increases, while the other party will not even accept a reduction in the spending growth rate.

In the 1940s we came together as a nation since we perceived the threat from Germany and Japan was real. We had a sense of urgency because we understood there was no time to waste dickering over the details. We took pride in making the necessary sacrifices, however small, while many others made the ultimate sacrifice. There are several differences between the fiscal crisis we face today and World War II. Most Americans do not realize or accept that the fiscal grand canyon is real, and poses a serious threat to our country. As a result, our political parties believe they have all the time in the world to indulge in ideology rather than compromise. In the 1940s, the threat came from outside our borders, so it was far easier to unify the nation. No one outside our borders created the fiscal grand canyon. We did this to ourselves incrementally over a period of decades. It takes humility to accept responsibility for our mistakes, and wisdom to resist the temptation to point fingers at others. The best news is since we created the fiscal grand canyon, we can fix it. All we have to do is build a bridge based on compromise, common sense and determination.

We put a man on the moon in less than nine years, so we can get our economy back into balance within 10 years if the plan is based on common sense and we are determined. One of the mistakes Europe has made is forcing countries to slash government spending while a country is in recession. The Europeans (Germans) have a staunch belief that getting a country’s budget down to 3% of GDP as fast as possible is some sort of panacea, or retribution on the spendthrifts in the EU. Under the current circumstances, it’s a financial form of bloodletting, which is why Greece and Spain continue to weaken. Our economy is recovering from a credit bubble that took 30 years to create, and it will take time for all the imbalances to be righted, whether we like it or not. The plan must be gradual so the adjustments, some combination of tax increases and slowing down the growth rate of government spending, are spread out over the next six years. The goal is that within six years, government spending will be down to 19.05% of GDP, and receipts up to at least 18.26%, their long-term averages. With tax receipts currently at 16.1% of GDP and spending near 24.8% of GDP, we have two problems, so we need two solutions.

At the risk of standing on a soapbox, Congress never explains the budget process. This can be self-serving and misleading for most Americans. Every year Congress establishes a baseline spending level for each of the next seven years. Each year’s spending level becomes the baseline. All future changes in spending are referenced to the baseline. For instance, if spending on defense and Medicare is budgeted to increase by 3% in the next two years, any additional spending above the baseline’s 3% growth rate is deemed an increase in spending. Any reduction below the baseline’s 3% growth rate is called a cut in spending. So, if the growth rate of next year’s spending on defense and Medicare were lowered from 3 to 2.9%, members of Congress would say they cut spending, even though spending is going to increase 2.9%. In order to lower government spending from 24.8% of GDP to 19.4% over the next six years, Congress could consider only spending 99% of next year’s baseline for every item in the budget. One advantage to this approach is there would be nothing to debate since every program is cut and every program is impacted to the same degree. If this process was continued for the next six years, the increase in government spending against the baseline would gradually slow.

As we have often discussed in the past, economic growth is likely to be restrained, while the imbalances from the credit bubble are worked through. Extensive research on growth rates after a credit bubble suggests that GDP is likely to grow 1 to 1.5% less in the 10 years following a credit bubble reversal. This suggests that GDP is unlikely to grow above 2.0% on a sustained basis in coming years. The plan should incorporate this expectation for slower growth, so surprises are more likely to be positive. It will also reinforce why gradually slowing government spending growth is prudent. If government spending grew less than 2% annually, at some point in the next three to six years the private economy would begin to grow faster than 2%, which accomplishes two things. Government spending as a percent of GDP will shrink, and tax receipts will increase from organic economic growth. However, in the short run, tax increases need to be considered. If we are to come together as a nation, it must be clear that everyone is on board. According to the nonpartisan Tax Policy Center, 46.4% of workers pay no federal income taxes, but that is because their income is so low. According to IRS data, the top 10% of wage earners pay more than 70% of total personal income taxes, so the tax code is already fairly progressive. However, these figures mask the income inequality that has developed, especially over the last 15 years. At the end of 2010, 19.8% of total pretax income went to the top 1% of wage earners. Since this figure includes capital gains from the stock market, their share of total income is likely even higher now. After peaking at 23.9% in 1928, the percent of pretax income going to the top 1% of wage earners fell to under 15% in 1942, and stayed under 15% until 1995. The most recent peak occurred in 2007, when the top 1% received 23.5% of total pretax income. These figures are based on IRS data as analyzed by Emmanuel Saez, an economics professor at the University of California, and Thomas Piketty, an economics professor at the Paris School of Economics, and were provided to us by Philippa Dunne from the Liscio Report (www.theliscioreport.com).

As we have often discussed in the past, economic growth is likely to be restrained, while the imbalances from the credit bubble are worked through. Extensive research on growth rates after a credit bubble suggests that GDP is likely to grow 1 to 1.5% less in the 10 years following a credit bubble reversal. This suggests that GDP is unlikely to grow above 2.0% on a sustained basis in coming years. The plan should incorporate this expectation for slower growth, so surprises are more likely to be positive. It will also reinforce why gradually slowing government spending growth is prudent. If government spending grew less than 2% annually, at some point in the next three to six years the private economy would begin to grow faster than 2%, which accomplishes two things. Government spending as a percent of GDP will shrink, and tax receipts will increase from organic economic growth. However, in the short run, tax increases need to be considered. If we are to come together as a nation, it must be clear that everyone is on board. According to the nonpartisan Tax Policy Center, 46.4% of workers pay no federal income taxes, but that is because their income is so low. According to IRS data, the top 10% of wage earners pay more than 70% of total personal income taxes, so the tax code is already fairly progressive. However, these figures mask the income inequality that has developed, especially over the last 15 years. At the end of 2010, 19.8% of total pretax income went to the top 1% of wage earners. Since this figure includes capital gains from the stock market, their share of total income is likely even higher now. After peaking at 23.9% in 1928, the percent of pretax income going to the top 1% of wage earners fell to under 15% in 1942, and stayed under 15% until 1995. The most recent peak occurred in 2007, when the top 1% received 23.5% of total pretax income. These figures are based on IRS data as analyzed by Emmanuel Saez, an economics professor at the University of California, and Thomas Piketty, an economics professor at the Paris School of Economics, and were provided to us by Philippa Dunne from the Liscio Report (www.theliscioreport.com).

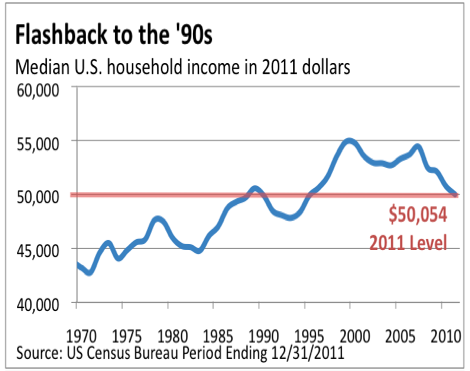

The average CEO of an S&P 500 company is making 780 times the median income of the average worker’s $50,054 income, or about $3.9 million. We’re no fan of higher taxes, but the imbalance in income distribution is a problem that can only be addressed in the short run with higher taxes, since company boards are unlikely to change compensation packages. If Congress chose to increase taxes on the top 10% of wage earners so an additional $125 billion in tax receipts were generated, those funds could reverse the $95 billion in higher taxes workers will pay in 2013 when the 2% reduction in social security taxes is reversed. For the average worker that will amount to about $20 a week. Median household income has declined in each of the last four years, and is now down to 1995 levels, which coincidently is when income going to the top 1% exceeded 15% for the first time since 1942.

Corporate balance sheets have never been stronger, with most companies holding a significant level of cash. We have millions of unemployed who just want a job and millions more wanting to work full time instead of part time. The only thing we have to fear is uncertainty. A plan that incorporates common sense goals and the path to reach them would eliminate much of the uncertainty that keeps business owners from moving forward. Our country is facing a crisis that calls for leadership, and someone who can communicate the scope of our crisis with a sense of urgency, as well as convince the American people it is time for collective sacrifice. It wouldn’t hurt if both parties made John F. Kennedy’s mantra their own: “Ask not what your country can do for you – ask what you can do for your country.” Enough of the soapbox.

FEDERAL RESERVE

The primary benefit of the Fed’s decision to launch QE3 now is the certainty provided by targeting improvement in the labor market, and continuing until job growth improves. With so much uncertainty surrounding fiscal policy, developments in Europe, and growth in China, there can be no doubt about the direction of monetary policy in the U.S. The Fed’s decision to not have an ending date or a ceiling on its purchases is brilliant. For the foreseeable future, there will be no countdown to the end of QE3, no possibility for conjecture about a QE4, and mercifully no debate about whether they will or won’t or should do QE4. The Federal Reserve is simply all in.

GDP growth in the second quarter was 1.7%, and as the Fed noted in its Federal Open Market Committee press release, “Economic activity has continued to expand at a moderate pace in recent months. Growth in employment has been slow, and the unemployment rate remains elevated. Household spending has continued to advance, but growth in business fixed investment appears to have slowed.” Effectively the economy is growing at stall speed, which means it is vulnerable to significant downside risks posed by strains in global financial markets. What the press release tactfully did not mention are the significant risks from fiscal policy that Congress must address very soon. In 2013, fiscal policy will be a drag on economic growth. The only unknown is how much of a drag.

By announcing QE3 now, the economy may get a bit of a lift before the drag from fiscal policy begins to bite in the first half of 2013. According to the laws of physics, it takes less energy to lift an object that is in a state of stasis, than one which is falling, since energy is expended arresting the decline. We thought the Federal Reserve would wait to see how Congress dealt with the fiscal cliff, and keep QE3 as their “ace in the hole.” The Fed chose to get out ahead of the curve and not wait to act until slowing materialized. One of the mistakes the Fed made in 2008 was being behind the curve. We think the Federal Reserve made the right choice.

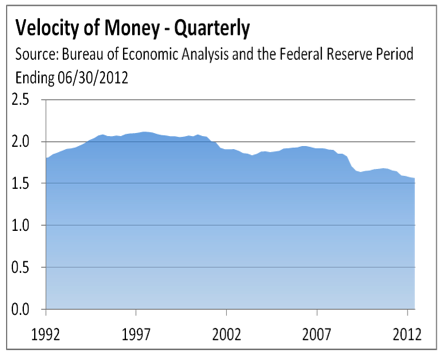

The Federal Reserve has expanded its balance sheet from $900 billion in April 2008 to $2.8 trillion. A year from now it will top $3.5 trillion, if the Fed is still in QE3 mode. But most of the expansion in the Fed’s balance sheet has not made it into the economy. Banks have parked $1.6 trillion in excess reserves with the Fed, and that money is going nowhere fast. The formal definition of GDP is: GDP = money supply (M2) multiplied by velocity (turnover rate). If money supply increases, and the velocity of money remains the same, GDP growth will pick up. If an increase in confidence causes velocity to quicken, and money supply rises, GDP growth will surge. Conversely, if money supply grows by 5%, but velocity slows by 5%, GDP will remain stagnant. It is noteworthy that after all of the Fed’s efforts and extraordinary monetary accommodation, the velocity of money has fallen to its lowest turnover rate in 50 years. A recent report from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation showed that at the end of the second quarter insured deposits reached a new record of $10.3 trillion, despite negligible yields. The weakness in monetary velocity and record deposits, underscores the degree of uncertainty felt by most consumers and business executives. They hear about the looming fiscal cliff, remember how well Congress handled the debt ceiling issue last August, and feel the best course of action is to do nothing. All of this reinforces our conviction that dealing with the fiscal grand canyon and lowering fiscal uncertainty for 2013 and beyond would be very helpful in getting money moving again.

The Federal Reserve has expanded its balance sheet from $900 billion in April 2008 to $2.8 trillion. A year from now it will top $3.5 trillion, if the Fed is still in QE3 mode. But most of the expansion in the Fed’s balance sheet has not made it into the economy. Banks have parked $1.6 trillion in excess reserves with the Fed, and that money is going nowhere fast. The formal definition of GDP is: GDP = money supply (M2) multiplied by velocity (turnover rate). If money supply increases, and the velocity of money remains the same, GDP growth will pick up. If an increase in confidence causes velocity to quicken, and money supply rises, GDP growth will surge. Conversely, if money supply grows by 5%, but velocity slows by 5%, GDP will remain stagnant. It is noteworthy that after all of the Fed’s efforts and extraordinary monetary accommodation, the velocity of money has fallen to its lowest turnover rate in 50 years. A recent report from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation showed that at the end of the second quarter insured deposits reached a new record of $10.3 trillion, despite negligible yields. The weakness in monetary velocity and record deposits, underscores the degree of uncertainty felt by most consumers and business executives. They hear about the looming fiscal cliff, remember how well Congress handled the debt ceiling issue last August, and feel the best course of action is to do nothing. All of this reinforces our conviction that dealing with the fiscal grand canyon and lowering fiscal uncertainty for 2013 and beyond would be very helpful in getting money moving again.

U.S. ECONOMY

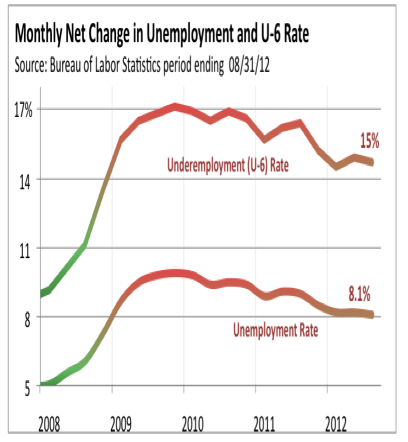

The Federal Reserve has never linked monetary policy to a specific economic statistic, so their decision to tie policy to a substantial improvement in the labor market is unprecedented. However, it is merely an extension of their policy ma ndate to foster maximum employment. For a self-sustaining expansion to take hold, job growth must be strong enough to get the unemployment rate down. In order for that to happen, job growth must exceed the growth rate of the labor force. As we have noted, job growth does not begin at zero, but at 110,000, since that is the number of jobs needed to absorb new entrants into the labor market. The current recovery has created about half the average number of jobs as in prior post-World War II recoveries, despite unprecedented fiscal stimulus and monetary accommodation.

The Federal Reserve has never linked monetary policy to a specific economic statistic, so their decision to tie policy to a substantial improvement in the labor market is unprecedented. However, it is merely an extension of their policy ma ndate to foster maximum employment. For a self-sustaining expansion to take hold, job growth must be strong enough to get the unemployment rate down. In order for that to happen, job growth must exceed the growth rate of the labor force. As we have noted, job growth does not begin at zero, but at 110,000, since that is the number of jobs needed to absorb new entrants into the labor market. The current recovery has created about half the average number of jobs as in prior post-World War II recoveries, despite unprecedented fiscal stimulus and monetary accommodation.

According to the National Employment Law Project, a majority of jobs lost during the recession were in the middle range of wages. Their analysis included 366 occupations traced by the U.S. Department of Labor. They created three equal groups, with each representing one-third of total employment in 2008. Officially, the recession began in December 2007 and ended in June 2009. The middle-third group had median wages of $13.84 to $21.13 and accounted for 60% of job losses between January 1, 2008 and early 2010. Unfortunately, only 22% of all jobs created since early 2010 have been in the middle-third of the labor market. This data strongly suggests that many workers are being forced to accept lower paying jobs, since the lower-third group has accounted for 58% of total job growth since early 2010, but only accounted for 21% of jobs lost during the recession.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, median annual household income fell for the fourth straight year in 2011 to $50,054. The median is the number at which half the households are above, and half below. Since the end of 1999, median household income has declined 8.9% from its all time high of $54,932, and is now where it was in 1991. The labor participation rate fell to its lowest level since 1981 in August, as millions of unemployed and discouraged workers have simply given up looking for a job. In August, the unemployment rate dipped to 8.1% because 368,000 workers dropped out of the labor force. This is an obvious flaw in the Department of Labor’s methodology, since it suggests the unemployment rate would drop to 6%, if we could just get another 4 million unemployed job seekers to throw in the towel. If half of those who have given up looking for work were included in the labor market, the unemployment rate would be 9.5% or higher.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, median annual household income fell for the fourth straight year in 2011 to $50,054. The median is the number at which half the households are above, and half below. Since the end of 1999, median household income has declined 8.9% from its all time high of $54,932, and is now where it was in 1991. The labor participation rate fell to its lowest level since 1981 in August, as millions of unemployed and discouraged workers have simply given up looking for a job. In August, the unemployment rate dipped to 8.1% because 368,000 workers dropped out of the labor force. This is an obvious flaw in the Department of Labor’s methodology, since it suggests the unemployment rate would drop to 6%, if we could just get another 4 million unemployed job seekers to throw in the towel. If half of those who have given up looking for work were included in the labor market, the unemployment rate would be 9.5% or higher.

Recently, much has been made of the improvement in housing. We think some of the exuberance is overdone and likely premature. But let’s put it in perspective. In 2006, new home construction represented over 6% of GDP. After declining by more than 60%, it now is 2.3%. If housing increases by 20%, it will add less than 0.5% to GDP. One of the headwinds still haunting housing is that lending standards remain tight for mortgages. The median credit score for an approved mortgage loan has increased by 40% since 2006, and “now exceeds by a considerable margin” the average of the last 12 years, according to the Federal Reserve. The low level of inventory for sale is a plus, but it is the result of 20 to 25% of existing homeowners being underwater on their mortgage, which means they are also removed from the demand side of the equation.

Recently, much has been made of the improvement in housing. We think some of the exuberance is overdone and likely premature. But let’s put it in perspective. In 2006, new home construction represented over 6% of GDP. After declining by more than 60%, it now is 2.3%. If housing increases by 20%, it will add less than 0.5% to GDP. One of the headwinds still haunting housing is that lending standards remain tight for mortgages. The median credit score for an approved mortgage loan has increased by 40% since 2006, and “now exceeds by a considerable margin” the average of the last 12 years, according to the Federal Reserve. The low level of inventory for sale is a plus, but it is the result of 20 to 25% of existing homeowners being underwater on their mortgage, which means they are also removed from the demand side of the equation.

Consumer spending is 70% of GDP and has more than 30 times the impact of housing. Wages have increased a measly 1.7% from a year ago, while the real cost of living has risen by almost twice that amount. If Congress rescinds the 2% reduction in social security taxes, the net pay for the median worker will fall by $1,000. While improvement in housing is certainly a plus, the health of the labor market, and how Congress handles the fiscal grand canyon dwarfs the impact of housing.

After reviewing how weak the labor market continues to be, it is easy to understand why the Federal Reserve decided to target improvement in the labor market going forward. Its actions will help on the margin, but there is no meaningful direct link between buying mortgage-backed securities and job growth. The global economy is slowing, and there will be some drag on growth in the U.S. in 2013, no matter how well Congress handles the fiscal grand canyon.

EUROPE

The underlying problem that has spawned Europe’s sovereign debt and economic crisis is too much debt and too little economic growth. The end game for Greece came when its cost of borrowing rose to unsustainable levels, freezing Greece out of the capital markets, and into the arms of the European Union. The terms demanded that Greece lower its budget deficit to 3% of GDP by implementing severe austerity measures that have only deepened its recession and made it more difficult to shrink its deficit.

In recent months, Italy and especially Spain experienced an increase in their borrowing costs that looked like both were headed down the same path as Greece. To contain and reverse yields in Spain and Italy, the ECB announced its Outright Monetary Transaction (OMT) program. After receiving a request for assistance from a country, the ECB will buy unlimited quantities of that country’s bonds with maturities of less than three years. In return, the requesting country must agree to economic reforms that will surely limit some of its independence and control over its finances. And there, of course, is the rub for a country like Spain.

In recent months, Italy and especially Spain experienced an increase in their borrowing costs that looked like both were headed down the same path as Greece. To contain and reverse yields in Spain and Italy, the ECB announced its Outright Monetary Transaction (OMT) program. After receiving a request for assistance from a country, the ECB will buy unlimited quantities of that country’s bonds with maturities of less than three years. In return, the requesting country must agree to economic reforms that will surely limit some of its independence and control over its finances. And there, of course, is the rub for a country like Spain.

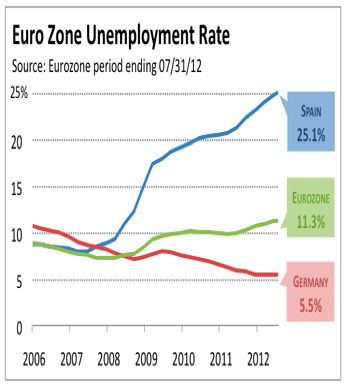

The unemployment rate in Spain is 25.1%, the economy is in recession, real estate values continue to fall and bad loans keep climbing. In July, the Bank of Spain reported that bad loans at Spanish banks rose to 9.8% of total assets. In June, Spain experienced a net capital outflow of more than $70 billion, according to the latest data available. This has caused the loan-to-core deposit ratio to soar to over 180% in July, forcing Spain’s banks to borrow $525 billion from the ECB. In October, Spain needs to refinance more than $30 billion, and, without a backstop from the ECB, it could prove challenging to float that much paper without causing yields to spike.

Spain has already pruned its budget in order to meet its budget deficit target of 3% in 2014. Last year’s deficit was 9.0% (barely higher than the United States’ 8.7% deficit), and a contracting economy will only make it harder to reach. Having already cut spending, Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy is reluctant to ask for the ECB’s help, since it will open the door for more cutbacks. That won’t bolster his political popularity, which is already falling. We don’t think he has any choice.

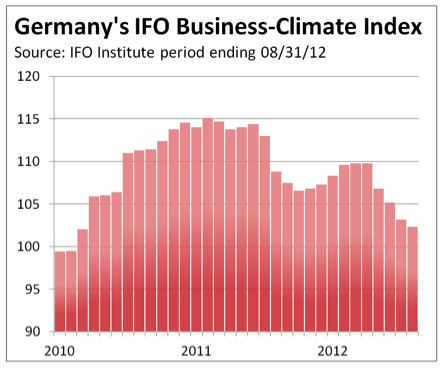

Europe is in recession and the ECB’s OMT program will not pull Europe out of it since it does little to spur growth. As we have noted previously, Italy’s average annual growth over the last 11 years is barely positive. Lowering yields in Spain and Italy will help postpone an immediate escalation of the crisis, but there are more chapters in this book. The last chapter will likely be whether Germany chooses to backstop the rest of the European Union. A recent poll showed that 65% of Germans think Germany would be better off without the common currency, and 49% think Germany would be better off outside the European Union. However, if Germany was on its own, its currency would soar, significantly hurting its exports. As we noted in last month’s commentary, Germany’s Ifo Business Climate Index has fallen to levels that has preceded a contraction in German GDP. As Europe’s recession gradually engulfs Germany, we’d wager the percent of Germans wanting out of the EU will increase.

Europe is in recession and the ECB’s OMT program will not pull Europe out of it since it does little to spur growth. As we have noted previously, Italy’s average annual growth over the last 11 years is barely positive. Lowering yields in Spain and Italy will help postpone an immediate escalation of the crisis, but there are more chapters in this book. The last chapter will likely be whether Germany chooses to backstop the rest of the European Union. A recent poll showed that 65% of Germans think Germany would be better off without the common currency, and 49% think Germany would be better off outside the European Union. However, if Germany was on its own, its currency would soar, significantly hurting its exports. As we noted in last month’s commentary, Germany’s Ifo Business Climate Index has fallen to levels that has preceded a contraction in German GDP. As Europe’s recession gradually engulfs Germany, we’d wager the percent of Germans wanting out of the EU will increase.

China and the Potential for a Rise in Protectionism

Global growth has been slowing as we suggested at the beginning of this year. Monetary policymakers are concerned, which is why the ECB is launching OMT, the Fed is cranking up QE3, and the Bank of Japan has expanded its asset purchasing plans. These new programs would not be needed, if prior efforts had succeeded in establishing self-sustaining recoveries. Over the next 12 months, there exists a high probability that U.S. growth will remain under 2%, Europe will continue to flounder and growth in China may slip further. This is not a pretty picture, and could provide a fertile environment for protectionism, as politicians play on public sentiment and enact laws to protect jobs and garner votes.

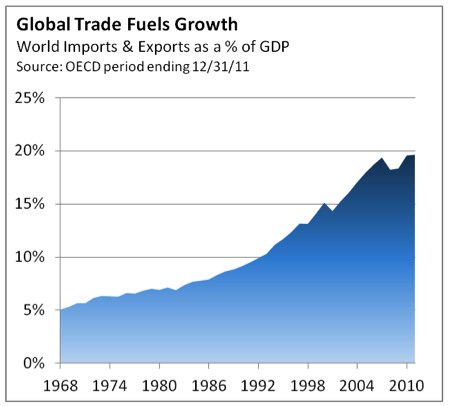

This anti-trade movement is in sharp contrast to the last 40 years, when the combined total of imports and exports rose from 5% to almost 20% of global GDP at the end of 2011. This trend was built on the back of globalization and willingness from countries to open their borders and enter into trade agreements, fostering an expansion of trade throughout the world. Over the last 20 years at least one billion people have experienced an increase in their standard of living, lifted by global trade. This remarkable record does not mean there aren’t a plethora of trade restrictions still in place. The U.S. has import restrictions to protect the sugar industry, so American consumers pay twice the world price for sugar, just to protect sugar industry jobs. The U.S. is not alone in this regard. We could cite every major country for using import or export restrictions or tariffs to protect a domestic industry. However, during difficult periods of slowing global growth, the temptation to use trade barriers has usually proved irresistible. As the Depression began to take hold in 1930, the United States passed the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act in June 1930 to protect American jobs. This incensed other countries who responded with their own trade protections. Within 18 months of the passage of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, world trade fell 40% and American imports and exports plunged by more than 50%, deepening the Depression.

This anti-trade movement is in sharp contrast to the last 40 years, when the combined total of imports and exports rose from 5% to almost 20% of global GDP at the end of 2011. This trend was built on the back of globalization and willingness from countries to open their borders and enter into trade agreements, fostering an expansion of trade throughout the world. Over the last 20 years at least one billion people have experienced an increase in their standard of living, lifted by global trade. This remarkable record does not mean there aren’t a plethora of trade restrictions still in place. The U.S. has import restrictions to protect the sugar industry, so American consumers pay twice the world price for sugar, just to protect sugar industry jobs. The U.S. is not alone in this regard. We could cite every major country for using import or export restrictions or tariffs to protect a domestic industry. However, during difficult periods of slowing global growth, the temptation to use trade barriers has usually proved irresistible. As the Depression began to take hold in 1930, the United States passed the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act in June 1930 to protect American jobs. This incensed other countries who responded with their own trade protections. Within 18 months of the passage of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, world trade fell 40% and American imports and exports plunged by more than 50%, deepening the Depression.

Since China has arguably been the main beneficiary from trade growth over the past decade, and is the world’s largest exporter, we expect China to be the target of trade disputes in the next two years. We expect China to respond aggressively, which will escalate trade frictions, and lead to more “Buy American” and “Buy European” campaigns. There is an old Chinese curse that seems appropriate for the situation: “May you live in interesting times.”

Macro Strategy Team

Investing involves risk, including possible loss of principal. The value of any financial instruments or markets mentioned herein can full as well as rise. Past performance does not guarantee future results.

This material is distributed for informational purposes only and should not be considered as investment advice, a recommendation of any particular security, strategy or investment product, or as an offer or solicitation with respect to the purchase or sale of any investment. Statistics, prices, estimates, forward-looking statements, and other information contained herein have been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but no guarantee is given as to their accuracy or completeness. All expressions of opinion are subject to change without notice.

What's been said:

Discussions found on the web: