Robert P. Seawright is the Chief Investment & Information Officer for Madison Avenue Securities, a boutique broker-dealer and investment advisory firm headquartered in San Diego, California. Bob is also a columnist for Research magazine, a Contributing Editor at Portfolioist as well as a contributor to the Financial Times, The Big Picture, The Wall Street Journal’s MarketWatch, Pragmatic Capitalism, and Advisor One.

~~~

Barry’s wonderful blog – although you may be re-thinking its wonderfulness given that I’m here – is, as you obviously know, called The Big Picture. His idea is to look at the investment universe using a very wide lens for a very broad audience, governed only by “facts, statistics, and informed, data-driven opinions.” Most fundamentally, he doesn’t want to miss the forest for the trees. He approaches “most investing issues with one foot in the behavioral camp, the other thrown in with the quants.” Intriguingly, behavioral finance meets quantitative analysis head-on when it comes to big picture analysis.

In a more perfect world – like the false one in which economists tend to live – investors would examine each new investment opportunity by evaluating it in context with other current and potential investments, goals, objectives and needs. If the expected return of the opportunity is sufficient on a risk-adjusted basis and if it would improve the investor’s position in the aggregate, the investor would then consider buying it (at the right price, though our economist friends seem to think that every price is the right price). Thus the investor would only get utility from the outcome of the investment indirectly, via its contribution to his or her total wealth and overall situation. But none of us is homo economicus. Instead, we tend to spend all our careful analysis on those pesky trees.

Narrow framing is the behavioral phenomenon whereby, when people are offered a new opportunity, they evaluate it in isolation, separately from their other holdings, opportunities and risks as well as their overall situation. In economic terms, they act as if they get utility directly from the outcome of the investment decision, even if and when the investment is just one of many that determines portfolio performance and risk. They also tend to put disproportionate emphasis on short-term returns.

As so often happens in behavioral finance, the classic demonstration of this concept is found in the work of Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman. In this instance, it comes from The Framing of Decisions and the Psychology of Choice (1981). Kahneman and Tversky asked subjects the following question.

Imagine that you face the following pair of concurrent decisions. First examine both decisions, then indicate the options you prefer:

Decision (i). Choose between:

A. a sure gain of $240

B. 25% chance to gain $1,000 and 75% chance to gain nothing

Decision (ii). Choose between:

C. a sure loss of $750

D. 75% chance to lose $1,000 and 25% chance to lose nothing.

They reported that 84 percent of subjects chose A and that 87 percent chose D. Moreover, 73 percent of subjects chose the combination of A and D, which offered, in the aggregate, a 25 percent chance to win $240 and a 75 percent chance to lose $760 – even though the B and C combo offered a better outcome, namely a 25 percent chance to win $250 and a 75 percent chance to lose $750. Since the subjects were students at Stanford University and at the University of British Columbia, the problem shouldn’t have been too difficult (though my younger son – who went to Berkeley and denigrates all things ‘furd – will surely disagree).

Thus instead of focusing on the combined outcome of decisions (i) and (ii), subjects focused on the outcome of each decision separately. Indeed, subjects who are asked only about decision (i) did overwhelmingly choose A and subjects asked only about decision (ii) did overwhelmingly choose D. Accordingly, the subjects didn’t maximize aggregate utility in a rational manner (shocking, I know).

One practical investment tidbit to take from this cognitive shortcoming is that investors tend to like diversification more in theory than in practice. They like the idea of diversification preventing loss but hate the idea (as in 2013) of diversification suppressing gain. Every money manager has met with a client after a great year and heard only about the position(s) that didn’t do as well rather than the great overall performance. As my wife often tells me (partly in jest), I don’t want much, I just want more.

A better investment process, then, is careful to evaluate every potential investment within the context of the entire portfolio as well as the investor’s overall situation. When we don’t and evaluate opportunities too narrowly, we can miss out on diversification opportunities. We can also miss out on quality opportunities in that we see too much risk even though the risk is much more limited within the context of the whole. We might even end up with an investment that, in large measure at least, potentially cancels another out or works against the investor’s overall objectives.

We also tend to invoke too narrow a frame in terms of time. When we evaluate potential performance over too narrow a time frame, we will surely miss some great opportunities. Axiomatically, long-term investors shouldn’t care what happens except over the long-term. But we do. And the time horizon we focus on makes a big difference to how we perceive and evaluate an investment.

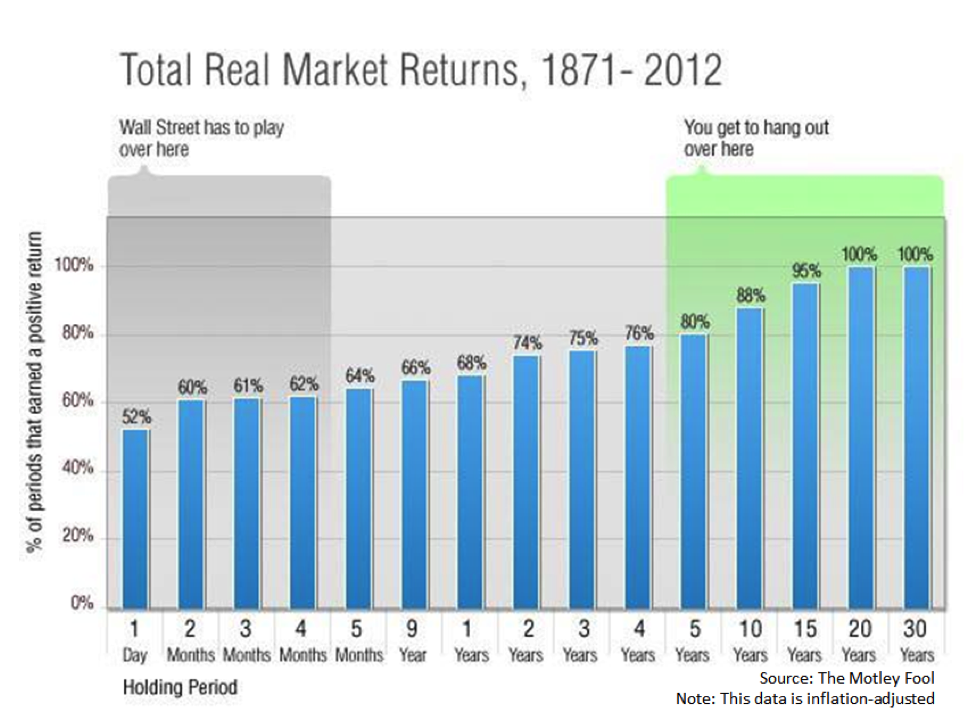

For example (see above), major equity indices post losses in nearly half of one-day periods and in about 40 percent of one, two and three-month periods – which makes them seem fairly dangerous, especially because we tend to be so risk and loss averse. But over five years we only observe losses about 20 percent of the time and almost never over 20 years and longer, even when adjusted for inflation. Many investors actually take too little risk because of a myopically narrow frame of reference. In other words, we misalign our decision frame to our objectives.

In practical terms, the problem is that we focus too much on yes or no? and not enough on a wider range of choices. As well as looking at individual opportunities, we should also consider (for example) whether another sector or even another asset class might work better. For even professional investors, narrow framing means too much analysis along the lines of Do I like it or not, and not enough along the lines of What am I/should I be after and does this opportunity really help in that regard?

When I (long ago, now) worked on a big-time Wall Street trading desk, our focus was almost exclusively on whether the security we were pushing at the time was rich or cheap (or at least upon whether we could construct an argument to make it seem rich or cheap). It was all about the trade today. Smart investors will take a much wider frame of reference and will focus instead upon the longer-term, value, risk (and not just volatility) in the context of his or her goals, objectives and needs. In other words, we should always focus on the big picture.

What's been said:

Discussions found on the web: