Does Moving for a Job Mean Higher Wages?

David Wiczer

St. Louis Fed, May 25, 2015

For more than 20 years, the number of people moving from state to state has been declining. A study by Raven Molloy, Christopher Smith and Abigail Wozniak found that the gross mobility rate has fallen by about 50 percent over this period.1 Both the causes and implications of this decline are not perfectly clear, but the authors want to tie the decline to the concurrent decline in many types of labor market transitions, such as job-to-job and occupation-to-occupation switches.

For more than 20 years, the number of people moving from state to state has been declining. A study by Raven Molloy, Christopher Smith and Abigail Wozniak found that the gross mobility rate has fallen by about 50 percent over this period.1 Both the causes and implications of this decline are not perfectly clear, but the authors want to tie the decline to the concurrent decline in many types of labor market transitions, such as job-to-job and occupation-to-occupation switches.

When thinking about the relationship between geographic mobility and occupational mobility, however, it is important to distinguish between those whose occupation change involves a spell of unemployment and those who transition directly from one job to another. The wage changes of these groups are quite different.

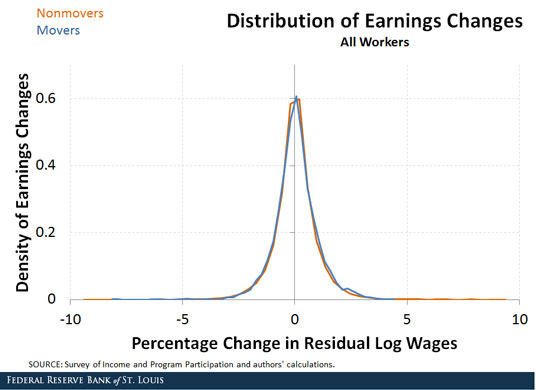

On average, the distribution of wage changes of workers who change occupation is similar whether or not they also make a geographic change. These two distributions are shown in the figure below.2

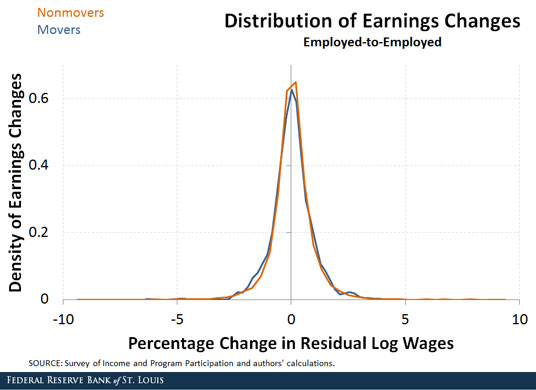

However, this includes both people making a direct job-to-job change and people going from being unemployed to employed. Those who moved to a new area and made a job-to-job change had a slightly lower change in wages than those who did not move.

Among those who were unemployed before finding jobs, the people who moved had significantly higher wage growth than people who did not move.

The explanation for this finding is far from obvious. On one hand, there may be a composition effect by which workers who cannot find a job locally are forced to move to find work. If this is the case, then the movers ought to have lower wages because moving is indicative of being an unattractive hire. But it also may be that unemployed workers have better outcomes if they are willing to look for jobs in a wider pool than their local labor market.

Which of these stories is more consistent with data determines how declining mobility should affect the outcomes of unemployed job seekers. According to the latter, declining mobility implies that workers are not searching broadly and are having worse results. One could equally interpret the causality in the other direction: While interstate mobility used to be a good option for the unemployed to find better jobs, there are fewer attractive offers to induce a geographic move as the overall hire rate falls.

Whatever the explanation, declining mobility is a stark feature of the labor market in recent years, and it is important to see how it affects (or is affected by) different groups.

Notes and References

1 Molloy, Raven; Smith, Christopher L.; and Wozniak, Abigail. “Declining Migration within the U.S.: The Role of the Labor Market,” Federal Reserve Board Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2013-27, April 2014. See also Kaplan, Greg and Schulhofer-Wohl, Sam. “Understanding the Long-Run Decline in Interstate Migration,” Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Working Paper 697, December 2013.

2 To construct the figures used in this post, we used data from the Survey of Income and Program Participation covering the period 1996-2013. We then took the wages before transitions and after jobs were found for any workers who reported changes in occupation. We averaged wages over all of the periods for each job stint and calculated percent differences (actually, log differences) between old and new occupations while skipping over periods of zero earnings during unemployment. We separate these transitions into four bins: those who change occupations, those who do not, those who move states and those who do not.

Additional Resources

- On the Economy: Pattern in Job Gains after Recessions Appears To Be Changing

- On the Economy: Living Arrangements, Labor Force Participation and Income

- On the Economy: How Long Until “Slack” Is Out of the Labor Market?

An interesting piece of food for thoughts , as always. I, anyhow, have a doubt (an unfortunately, no time to solve it). My problem is IF the time series 2006-2015 used as sources are portraying the job/wage universe of mid 2015. From 1996 up to now in many industries the progress of technology (mainly a more ‘intelligent’ tooling) has skewed labor force & output : one can see very easily, e.g., using economagic.com. In a very broad sense one can say that in time services have an increasing manpower vs production, and this makes quite a difference in wages, of course. I suspect that a clearer view of the matter requires first of all an analysis sector by sector. Just to give an example, wings manufacture of Boeing Dreamliner switched from 20 to 70 % of robotic assembly in a couple of years.