Source: NBER, Political Calculations

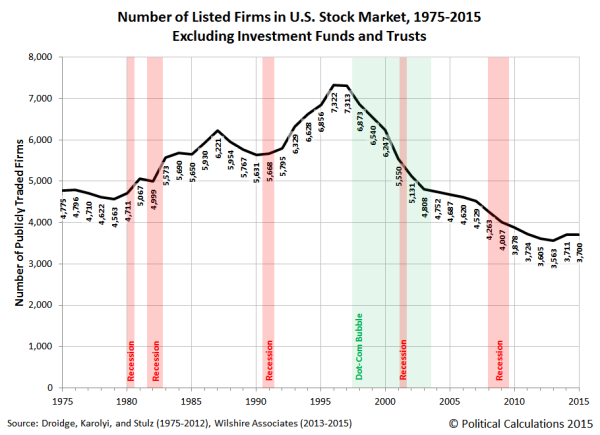

The U.S. now has half as many publicly listed companies trading on its exchanges as it did at the peak in 1996. As the chart below shows, listed companies reached a high of 7,322. That number today is down almost by half to 3,700 and is more than 1,000 lower than in 1975.

Why the number of listings has fallen so precipitously is the focus of “The Listing Gap,” a National Bureau of Economic Research report published last month. The authors, Craig Doidge of University of Toronto, G. Andrew Karolyi of Johnson Graduate School of Management at Cornell University, and René M. Stulz of Ohio State University, suggest a number of reasons for the decline. Much of the data and trend analysis they performed runs counter to commonly accepted Wall Street wisdom.

Why so few listings today? There are two forces at work: there has been a high number of delistings, accounting for roughly 46 percent of the decline; and a relatively low number of new listings, accounting for 54 percent. The authors’ explanations for these two may surprise you.

Let’s begin with the plunge in new listings: “The number of U.S. listings fell from 8,025 in 1996 to 4,101 in 2012, whereas non-U.S. listings increased from 30,734 to 39,427.” That’s a stark contrast. In other words, while new listings rose 28 percent overseas, they fell 49 percent in the U.S.

The researchers eliminated a few possible explanations. A lack of new startups or company formation wasn’t the issue: In the U.S., the total number of businesses remained little changed, and the number of startups actually increased. Nor was any one industry — or a handful of them — responsible for the decline; the authors noted that “listings decreased in all but one of the 49 industries after 1996.”

The study also looked into the old argument that “regulatory and legal changes in the early 2000s, including Regulation Fair Disclosure (‘Reg FD’) and the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (‘SOX’), made it more expensive” to list. These played little or no role because the decrease in new listings was “well on its way before these changes took place.” At worst, the regulatory burden accounts for only a small portion of the decline.

Then there are the delistings,which were driven by three main forces: mergers and acquisitions, failure to meet exchange listing requirements, and going private.

The costs and complexity of being a public company are often blamed for the increase in delistings, but the data doesn’t support that as a primary cause.

This was a common argument made after the adoption of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act in 2002. The general concern was the cost and complexity of compliance would lead more businesses — especially smaller ones — to go private. The data shows, however, that the “number of voluntary delists is far too small to explain the high number of delists.”

In contrast, mergers and acquisitions were a much larger source of delistings. The U.S. experienced an unusually high number of merger-related delistings after 1996 compared with both the U.S. historically and other countries. “From 1997 to 2012, the U.S. had 8,327 delists, of which 4,957 were due to mergers,” the researchers wrote. This accounts for almost 45 percent of the delistings after the 1996 peak.

There is more data in the report that leads to some interesting questions:

• The pools of venture capital and private equity are considerably larger today than they were in 1996. Does this account for today’s tech bubble and prevalence of so-called unicorns, or startups with values of more than $1 billion?

• When companies such as Uber are well-funded through private offerings, they have little reason to go public. Is that a one-off or a broader trend?

• Are small closely held companies looking for an exit via acquisition or merger rather than an initial public offering?

• We have discussed the shortage of quality bonds; is there a similar shortage of equities?

• What does the low number of publicly traded companies mean for valuations? Does it in any way suggest that stocks are now valued higher than their long-term averages?

I can’t give you conclusive answers to any of these questions, but they are worth delving into further.

Originally published as: Where Have All the Public Companies Gone?

Certainly in the pharmaceutical industry where I worked for thirty years it was mergers. Less than 1/2 of the major companies exist today as did 20 or so years ago. IIRC Pfizer is now made up of seven former pharma companies in addition to the parent named one.

A private company can focus on the business they are in. A public company’s focus is often miisdirected by rogue shareholders demanding votes on ridiculously irrelevent issues, corporate raiders, regulations out the ying-yang and formulating policies and internal board governance that must be politically correct, often at the expense of company profits. And they better have a save the planet game plan.

Back in the day, all public companies had to do was pay off politicians and unions for smooth sailing with none of the other crap. That’s pretty much all private companies have to do know.

“Why so few listings today?”

Cost of capital > cost of equity?

Like a lot of trends, I suspect that the decline of the middle class has something to do with it. Only 10% of Americans even have pensions, and the vast majority of the stock market is owned by the top 5%.

Companies used to think of public ownership as something to be proud of, now it is just an inconvenient way to communicate with more than one owner. There was a time when the only way to raise hundreds of millions of dollars was to spread out the risk over thousands of people. Today, most business owners find it easier to just make a few phone calls.

The advantage is that a new idea can move to market very quickly, without having to jump through many hoops. The disadvantage is that global oligarchs have such unlimited funds that they may not even bother to vet a new idea before financing it.

The rise of alternatives in institutional and pension plan investments is probably a major reason as well. Lots of PE money sloshing around out there. If the pull backs in investments in hedge funds, PE, and other alternatives announced by some big pensions becomes a trend, then we may see PE putting more IPOs out with more new companies showing up in the public exchange listings. Free money from the Fed must make it easier to be in PE as well – interest rate increases may make PE less profitable.

http://www.marketwatch.com/story/kentucky-pensions-stubbornly-cling-to-private-equity-2015-06-24