We seem to really enjoy contemplating the money and lifestyles of the top 0.01 percent. The wealthiest Americans garner immense mind-share in the imaginations of the rest of the populace. We incessantly track the incomes of hedge-fund managers and other finance stars, the heirs to the Wal-Mart fortune and other $100 billion families. Don’t forget the Bloomberg Billionaires Index and the Forbes 400 and the wealthiest New Yorkers.

We are in short fascinated with other people’s wealth.

What about the rest of the income strata? As it turns out, there is a fascinating story there as well. It may not be as glitzy and luxe as theBillionaires Index, but it is a tale of gradual improvement. So says a recent data analysis on the Global Middle Class by the Pew Research Center.

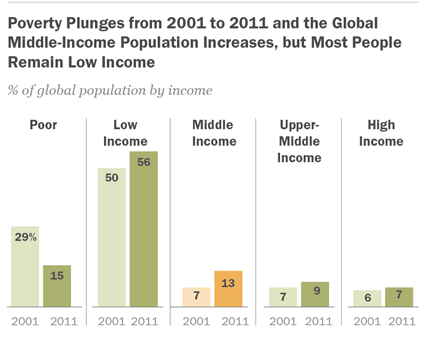

The good news is that during the first decade of the 21st century, about 700 million people were lifted out of poverty. That is a 14 percent reduction in poverty. The bad news is that moving into, and staying within, the global middle class is a significant challenge.

The study found that 71 percent of the global population is either poor (15 percent) or low-income (56 percent). The middle class is only 13 percent of the total population. To put some hard numbers on those percentages, with a world population of 7.2 billion humans, about 936 million are middle-class. A little more than a billion (1.08) are impoverished, and more than half the world’s population, a giant 4.03 billion people, are low-income.

Source: Pew Research Center analysis of data from the World Bank PovcalNet database and the Luxembourg Income Study database

The Pew report contains some astonishing data points: 84 percent of the world’s population, including those defined as middle-class, live on less than $20 a day. Surviving on the maximum in the U.S. or Europe would be difficult for an individual — about $7,300 a year.

Pew divided the world’s population into five groups: Poor, low-income, middle-income, upper-middle-income, and high-income. Less than $2 in daily per capita income is considered poor, based on data showing it takes that much to meet bare minimum human needs. Low-income is between $2 and $10, and to be part of the global middle-income group takes $10 to $20 a day. Note that for a family of four in the U.S., the poverty line is about $16.65 a day per capita. Income of $20 to $50 a day puts you in the upper-middle-income range. More than $50 a day, or about $73,000 a year for a family of four, and you are in the global high-income group.

It is noteworthy that while $10 is the lower threshold for middle-income status, it is about the median daily per capita income of U.S. households living in poverty. Pew reports that “a large share of poor people in the U.S. would also fail to meet the global middle-income standard.”

For readers who may not normally consider this demographic data, let me put this into a context that you may find more interesting or relevant. Each of these demographic and economic subgroups represents an enormous market for your favorite companies.

Consider the 71 percent of the world’s population that falls into the poor and low-income categories. This group devotes a very large share of its income to food, medicine, clothing, housing, education and energy. It therefore represents a huge market for basic goods and consumer staples.

Think of it another way. More than fourth-fifths of world’s population live on less than $20 a day. In other words, how well this vast swath of humanity is doing will have important implications for industry, from health care and finance to agriculture and energy.

Income growth in these groups in both the developing and developed world will alter the economic and political landscape. The U.S. National Intelligence Council has called it a global megatrend.

Not to be too optimistic, but the economic state of world is getting better. As more people move into the global middle class, they are able to buy more consumer goods, save and invest. That creates a long-term self-interest in political stability and, one can hope, democratic institutions.

How well we adapt to these changes will determine how successful we in the U.S. are as investors, and as a nation.

Originally published as: How Wealthy Is Everyone Who Isn’t Rich?

In some ways, a portion of the ‘top’ percent fit into the category of the Millionaire Next Door: those who didn’t exploit everyone else to gain their wealth; those who remained humble and grounded, respecting their fellow man; those who hid their light under a bushel and didn’t become ostentatious in their behavior; those who continued as human beings without succumbing to hubris.

And only wishing for the right to bear arms against the crazies, tax cuts so they can humbly create jobs, spaghetti blob off shore trusts to let their humble children and grandchildren follow in the glittering high heek steps of the Hilton’s and above all, the teaching of all the truths about the creation of all things and prayer in the school.

If the evening news, TMZ, and other gossip junk would spend time on “the heroes of our time”, i.e. the 70% who make do with what they earn and still manage to put ethics in their kids, then the poison in our culture would dilute in a sea of good.

Instead, we have the K-family and all kinds of (wannabee-) movie stars and “moguls” acting like lunatics, obviously never having been told by their mamma and papa that they should be a role model for the generations of their time.

I live in a very upscale town in Fairfield County, Ct.. I am reminded on almost a daily basis how selfish and self centered the upper class citizens can be in their day to day actions in public. It’s pretty striking at times. But, more importantly, their children, who, of course, are the reason they live here, are watching and learning at the same time. I fear that they will grow up to be worse.

Luckily, the upper class citizens’ children are few and far between, way under replacement level so eventually the unwashed will end up living in their sumptuous estates.