Fiscal Policy and the Long-Run Neutral Real Interest Rate

Narayana Kocherlakota

President, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis

Bundesbank Conference Frankfurt, Germany, July 9, 2015

Thanks for the introduction and the invitation to be here today.

In my remarks today, I will make three points about the U.S. economy.

First, there has been a significant decline in the long-run real interest rate, reflecting (in large part) a decline in what is sometimes called the long-run neutral real interest rate. (By the long-run neutral real interest rate, I mean the real interest rate that I expect to prevail when the economy is at maximum employment and inflation is at the central bank’s target.) Second, this decline in the long-run neutral real interest rate is likely to mean that monetary policymakers will be more constrained by the lower bound on thenominal interest rate in the future than they have been in the past.

My third point concerns an important connection between monetary and fiscal policy. I consider a permanent increase in the market value of the public debt, financed by an increase in taxes or reduction in transfers. This policy change increases the supply of assets available to investors. I argue that, in a wide class of plausible economic models, such an increase in supply would push downward on debt prices, and so upward on the long-run neutral real interest rate.

When I put these three points together, I reach my main conclusion. The decline in the long-run neutral real interest rate increases the likelihood that the economy will run into the lower bound on nominal interest rates. Accordingly, there is an enhanced risk that the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) will undershoot its maximum employment and 2 percent inflation objectives. Fiscal policymakers can mitigate this risk by choosing to maintain higher levels of public debt than markets currently anticipate.

I want to be clear at the outset that I am not saying that it is appropriate for fiscal policymakers to increase the long-run level of public debt. I am simply pointing to one benefit associated with such an increase: It allows the central bank to be more effective in mitigating the impact of adverse shocks to aggregate demand. I will point to other costs (and benefits) associated with increasing the level of public debt. Sorting through them is outside the scope of my remarks today, and really outside of my purview as a monetary policymaker.

My remarks today reflect my own views, and are not necessarily those of others in the Federal Reserve System.

Context: What is the Neutral Real Interest Rate?

I begin with some context: What do I mean by the neutral real interest rate?

The neutral real interest rate refers to the real interest rate that would prevail if the economy were at maximum employment and inflation were at target. The neutral real interest rate is a latent—that is, unobservable—variable. But it is a critical variable for monetary policymakers. The goal of the FOMC is to achieve maximum employment and keep inflation at 2 percent over the longer run. Definitionally, the FOMC can achieve this goal only by ensuring that the market real interest rate is, in fact, equal to the neutral real interest rate over the longer run. In contrast, if the market real interest rate is expected to be too high relative to the neutral real interest rate, then the FOMC is providing insufficient accommodation. In such a case, I would generally expect the inflation rate to run below target and employment to be below its maximal level.

As I say, the neutral real interest rate is unobserved. However, there is valuable information about the expected neutral real interest rate in the behavior of observed real interest rates and inflation forecasts. I next turn to how to best use that information.

Point 1: The Decline in the Long-Run Neutral Real Interest Rate

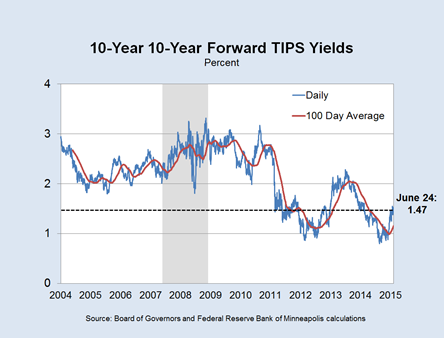

My first point is that the long-run neutral real interest rate has declined over the past few years in the United States. We can see evidence of this decline in the recent behavior of the long-runmarket real interest rate. Consider the behavior of the 10 year-10 year forward yield on Treasury Inflation Protected Securities (TIPs). This is a measure of what financial markets expect the annual real interest rate to average over the 10-year period that starts 10 years from the current date.

If we go back to the period between the second half of 2004 and the first half of 2007–before the onset of the global financial crisis—the 10 year-10 year forward TIPS yield varied between 2 percent and 2.5 percent. Over the past year, it has been below 1.5 percent.

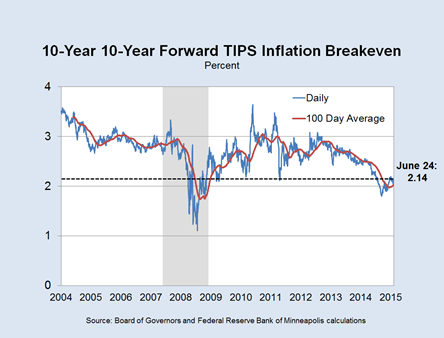

There are at least two possible reasons that market real interest rates could have declined. The first is that the long-run neutral real interest rate has declined. The second is that investors expect looser monetary policy, conditional on an unchanged long-run neutral real interest rate. To disentangle these two possible explanations, it is helpful to look at the behavior of inflation forecasts implied by financial market data. This graph depicts the behavior of 10 year-10 year forward inflation breakevens imputed from TIPs bonds. This is a measure of anticipated inflation over a 10-year period that begins 10 years from the current date. The graph shows that anticipated average inflation has risen little over the past year, and may well have fallen. This suggests that the decline in the long-run market real interest rate is associated with investors expecting tighter monetary policy in the future, not looser policy. I conclude that the long-run neutral real interest rate has also declined – and possibly by even more than the long-run real interest rate itself.

Point 2: Binding Lower Bound on Nominal Interest Rates

I now turn to my second point: the challenge for the FOMC created by this decline in the neutral real interest rate.

With a lower long-run neutral real interest rate, the long-run federal funds rate will be correspondingly lower (for any given inflation target). As a consequence, the FOMC has less monetary policy “space,” as it is more likely to be constrained by the lower bound on nominal interest rates. Of course, it is true that, during the recent stay at the zero lower bound, the FOMC has used unconventional policies like purchases of long-term assets as a way to generate additional monetary accommodation. My reading of the available evidence is that it is consistent with the hypothesis that these unconventional policies were supportive of prices and employment. However, it also seems clear that central banks see costs associated with these tools. Given these costs, I anticipate that monetary policy will be insufficiently accommodative during periods at the nominal interest rate lower bound, which will lead the economy to undershoot the FOMC’s inflation and employment objectives.

Point 3: Public Debt Levels and the Long-Run Neutral Real Interest Rate

I now turn to the impact of an increase in the level of public debt, funded by higher future taxes or lower future transfers, on the long-run neutral real interest rate. (My analysis here is agnostic about how the government uses the funds generated by the initial new debt issue.) The baseline thinking about the level of public debt and the neutral real interest rate is shaped by Robert Barro’s (1974) formulation of Ricardian equivalence. The heart of Ricardian equivalence is that additional issuance of public debt leads households to demand more assets in order to save for anticipated future taxes needed to service the extra debt. The ultimate impact of an addition to public debt on the neutral real interest rate depends on how that increase is offset by the increase in households’ asset demand. Under Ricardian equivalence, the offsetting is perfect, and there is no impact on the long-run neutral real interest rate. This hypothesis underlies the basic New Keynesian model.

However, there are many models of the economy in which Ricardian equivalence does not hold. In these models, those who buy the government bonds are not the same as those who pay the future taxes. I’ll cite two examples of such models. The first is the overlapping generations framework pioneered by Paul Samuelson (1958) and Peter Diamond (1965). In this model, many of the buyers of additional debt die before the service on that debt has to be repaid. Hence, increasing the supply of public debt does not generate an offsetting increase in the demand for assets, and the long-run neutral real interest rate rises.

The second is the incomplete markets class of models of Truman Bewley (1986) and S. Rao Aiyagari (1994). In this kind of model, at least some agents face binding borrowing constraints at any point in time. On the margin, any additional debt issuance will be purchased only by the unconstrained agents, but all agents have to pay the taxes required to service the extra debt. This asymmetry between who wants to buy the debt, and who pays for its service, again means that additional debt issuance pushes up on the long-run neutral real interest rate.

The overlapping generations and incomplete markets models of the effects of public debt issuance both seem to me to be more plausible than the fully Ricardian mechanism that I discussed earlier. These models imply that fiscal authorities can push up on the long-run neutral real interest rate by issuing more public debt. My main point is that, by raising the long-run neutral real interest rate, this additional debt issuance would reduce the likelihood of the FOMC’s hitting the lower bound on the nominal interest rate. The FOMC would be better able to achieve its employment and price objectives.

To be clear, as I noted in the introduction, I am not arguing in favor of extra debt issuance. Models in which Ricardian equivalence does not hold typically imply that there are winners and losers associated with additional government debt issuance. Balancing these gains versus losses is clearly a job for the fiscal authority, not for monetary policymakers like me.

Conclusion

Let me wrap up by summarizing my argument one last time.

There has been a significant decline in the long-run neutral real interest rate in the United States over the past few years. This decline in the long-run neutral real interest rate increases the future likelihood that the FOMC will be unable to achieve its objectives because of a binding lower bound on the nominal interest rate. Plausible economic models imply that the fiscal authority can mitigate this problem by issuing more public debt, although such issuance is not without cost. It is, of course, the province of the fiscal authority to determine whether those costs are worth the benefit that I’ve emphasized today.

Thanks for your attention.

Endnote

1 I thank Manuel Amador, Terry Fitzgerald, Sam Schulhofer-Wohl and Kei-Mu Yi for their thoughtful comments.

References

Aiyagari, S. Rao. 1994. Uninsured Idiosyncratic Risk and Aggregate Saving. Quarterly Journal of Economics 109 (3): 659-84.

Barro, Robert. 1974. Are Government Bonds Net Wealth? Journal of Political Economy 82 (6): 1095-1117.

Bewley, Truman F. 1986. Stationary Monetary Equilibrium with a Continuum of Independently Fluctuating Consumers. InContributions to Mathematical Economics in Honor of Gerard Debreu, edited by Werner Hildenbrand and Andreu Mas-Colell. Amsterdam: North-Holland, pp. 79-102.

Diamond, Peter. 1965. National Debt in a Neoclassical Growth Model. American Economic Review 55 (5): 1126-50.

Samuelson, Paul. 1958. An Exact Consumption-Loan Model of Interest with or without the Social Contrivance of Money. Journal of Political Economy 66 (6): 467-82.