Source: Bloomberg News

Bad brokers don’t leave the business; they just move on to a different firm.

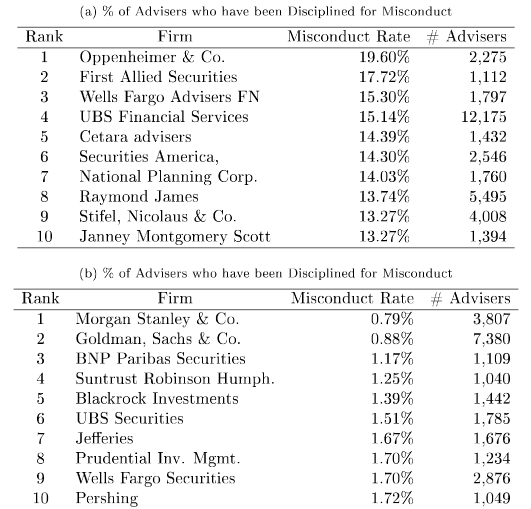

That is one of the key findings of a study of broker misconduct by professors at the business schools of the University of Chicago and University of Minnesota. The study, titled “The Market for Financial Adviser Misconduct,” reviewed broker disciplinary records from 2005 to 2015 stored in the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority’s BrokerCheck database, covering almost 4,000 securities firms employing about 640,000 brokers.

There is an enormous wealth of information that is publicly available about brokers who violate the suitability rules and other standards of conduct. What the study found was that misconduct that resulted in disciplinary action was widespread, with one in 13 brokers having a misconduct-related disclosure on their Finra files.

There is no other way to put this: That’s just astonishing. To their credit, many brokerages try to take appropriate action.

As Bloomberg News reported yesterday, “Misconduct isn’t left unchecked by financial firms. About half of advisers found to have committed misconduct are fired.”

My colleague Michael Batnick plowed through the 60 page report to pull more data from the study. He found that:

- About a third of brokers with misconduct records are repeat offenders.

- Past offenders are five times more likely to engage in misconduct than the average adviser, even compared with other advisers in the same firm at the same point in time.

- Brokers working for firms whose executives and officers have records of misconduct are more than twice as likely to engage in misconduct.

- Almost half of the brokers who engage in misconduct in a given year don’t keep their jobs into the next year. However, almost half of the brokers (44 percent) who lost their jobs due to misconduct found employment in the industry within a year.

- Among currently registered brokers, 7.56 percent engaged in misconduct at least once. Of those, 38 percent are repeat offenders.

Perhaps most dispiriting of all is that misconduct is even more common in counties filled with wealthy, elderly people. For example, the study found that of the “5,278 advisers in Palm Beach, Florida, 18.11% have engaged in misconduct.”

These numbers become even more astounding once you understand the standards of conduct for brokers. Finra, the industry-financed self-regulating authority, only requires that brokers adhere to a so-called suitability standard — meaning that they make recommendations that are supposed to be appropriate to the customer. It also happens to mean that it’s fine to recommend the products that are most rewarding for the broker. The tougher, better benchmark is the fiduciary standard, which requires someone to put the client’s interests ahead of their own. That makes me imagine what would happen if the fiduciary standard were applied to all brokers, as it will be later this year for those brokers dealing with retirement accounts. If that were the case, I think the rate of bad behavior would be shown to be even higher than it is in this report.

How is it possible that despite all of this readily available public information about bad broker behavior, investors continue to get abused? Two possible answers are that the information is much less easily accessible than we imagined, and that the marketplace for financial advice is terribly inefficient.

This isn’t a minor concern. Bad brokers cost investors billions of dollars a year, and much of the losses are never recovered because of the financial industry’s private justice system. (For more on this seethis and this.)

Just how much investor money is lost due to broker misconduct is, sadly, unknown. But we do have some idea of how much ethically dubious but legal behavior — such as conflicts of interest — costs investors: about $17 billion each year, according to a recent White House report.

One of the central rules of economics is that incentives matter. One way we can improve the behavior of brokers and others is to alter the incentives by simplifying the rules they must follow, and by raising the standards of conduct. The fiduciary standard accomplishes both and should be the guiding criterion for the industry.

Orignally: Broker Misconduct Is Worse Than We Thought

What's been said:

Discussions found on the web: