There is some good news in bank land.

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. just released its quarterly banking profile update (executive summary), and it is filled with signs of improvements in the state of the industry.

Just some highlights: Net operating revenue is rising, as is loan growth and revenue. Quarterly net income was the highest since the financial crisis at $43.6 billion, a $584 million increase from a year earlier. More than 60 percent of the nation’s banks reported profit growth, while just 4.5 percent of banks were money-losers. This is the lowest percent since the first quarter of 1998. (That sure seems like a lifetime ago.)

At the same time, the FDIC’s list of problem banks continues to shrink, as the dollar value of delinquent loans fell 3.4 percent. There are 147 ailing banks today versus 888 in early 2011. One modest sign of trouble: Noncurrent loans to commercial and industrial borrowers increased 8.9 percent, and net charge-offs of loans to these borrowers doubled from a year ago. You can thank trouble in the energy industry for that.

But here’s what really stands out. The FDIC’s deposit insurance fund — the rainy day reserve used to pay off depositors at failing FDIC insured institutions — is at a post-crisis high of $77.9 billion as of June 30 (although the reserve is still below its precrisis peak).

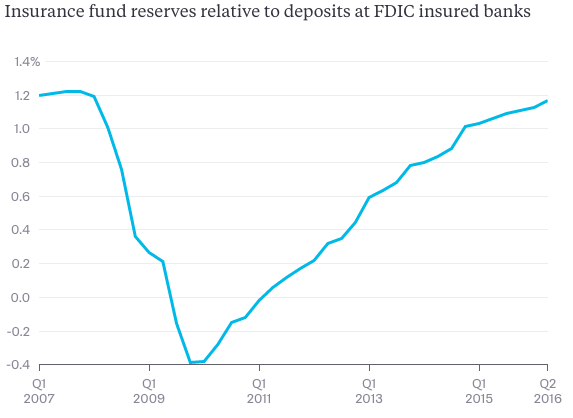

Just having a lot of money on hand may not be the most useful measure. A better yardstick is comparing the money in the insurance fund to the amount of insured deposits, otherwise known as the reserve ratio. This now stands 1.17 percent, surpassing the mandated minimum of 1.15 percent. The Dodd-Frank Act of 2010 requires that the reserve ratio reach 1.35 percent by Sept. 30, 2020. Just for the sake of perspective, the fund’s reserve ratio peaked at 1.39 percent in 1998, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland. The chart below shows how the reserve ratio has changed over time:

The FDIC has a self-imposed reserve target of 2 percent, which it isn’t expected to hit until 2027. That, of course, contains a pretty sizable assumption — that we don’t have another run on the banking system that depletes the fund.

What is unequivocally good news is not always perceived that way by the financial industry, however. I must admit to being perplexed by headlines like this: “FDIC Fund Has Rallied, But Get Ready to Keep Paying Premiums“ — as if the two were unrelated issues. The fees that banks pay as insurance premiums to FDIC is how the emergency fund accumulates reserves. If you want to have FDIC insurance, you should expect to keep paying these fees. Alternatively, some brave bank can drop its FDIC coverage and tell depositors that they will be paid slightly higher interest as a result of the savings from the cancelled deposit insurance. Guess what will happen to this bank’s deposit base?

Why does this matter? Even though the FDIC is an independent regulatory body with a board and chairman appointed by the president, it is still a taxpayer-backed entity. According to a 2013 FDIC staff paper, the agency has authority to borrow as much as $100 billion for insurance losses from the U.S. Treasury. But there’s more than that really. According to the FDIC’s website, deposit insurance is backed by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government.

In others words, if the FDIC ever runs out of money in a financial meltdown, taxpayers are on the hook. So it’s a good thing that the money banks put up for the fund offers a first and growing line of defense.

This much I can guarantee: One day (let’s hope a long, long time from now), there will be another banking crisis. Whatever steps the FDIC is taking to build up its reserves now are welcome. Let’s hope the fund has enough money on hand so that taxpayers don’t have to be called on again.

Originally: Banking Poses a Shrinking Risk to Taxpayers

What's been said:

Discussions found on the web: