New York Cabs Shouldn’t Get a Government Bailout

The city can’t be in the business of offering do-overs for people who made bad investments.

Bloomberg, October 17, 2019

Bad ideas tend to naturally follow from bad investments. The latest example: Bailing out people who overpaid for taxi medallions, the city license that allows drivers to pick up riders who hail them on the streets of New York. This came about because Uber and Lyft have been taking market share at the expense of cabs, sending medallion values into a tailspin.

Just like too many homebuyers of the 2000s, medallion owners find themselves underwater on the purchase price, deep in debt and looking for a rescue. They should take a page from those same homeowners — and just walk away. Medallion owners can take full advantage of the bankruptcy system to discharge their debts, leaving those bad investments behind.1 It’s painful, but the sunk-cost fallacy teaches us we shouldn’t throw good money after bad.

Asking federal or municipal taxpayers to rescue cab owners from their own folly creates a moral hazard of the highest order. The issue affects a small number of taxi owners; it doesn’t present a broader systemic risk of any kind; and the entire matter is best handled through the existing bankruptcy system. Taxi medallions are not “too big to fail.”

Despite all of this, some of New York’s political leaders and Congressional members want a bailout for medallion owners.

A brief reminder of how we got here: The New York City Taxi and Limousine Commission was created in 1971 in response to corrupt police oversight of the taxi industry.2 But it wasn’t long before the TLC itself was subjected to regulatory capture, and stopped advocating on behalf of taxi riders and city residents. Instead, it became a front for medallion owners, intentionally limiting the number of medallions and therefor taxi cabs available.

Why? Because the medallions became so valuable. The TLC behaved as if its charge was to maximize the wealth of taxi owners, even if that worked to the detriment of taxi riders.

This fundamentally altered the properties of the medallions: They were supposed to be a license to drive a cab, but instead evolved into an investment asset. For almost four decades, taxi medallions were “the best investment in America.” From 1975 to 2013, medallions generated returns of 2,706%, outpacing the Dow Jones Industrial Average’s gain of 1,675% or gold’s 846% increase. By 2013, the value of all New York taxi medallions was $16.6 billion.3

That incredible wealth distorted the TLC’s mandate. Its mission was to oversee an industry that is an essential part of the New York City’s transportation network. Its constituency was supposed to include passengers, drivers, vehicle owners, taxpayers and local businesses. The TLC lost sight of that, working instead to protect the interests of the medallion owners by limiting the supply — by acting, in short, like monopolists.

Consider the city’s growth in population and medallions. In 1937, there were about 16,900 taxis licensed to pick up curbside passenger hails. In the ensuing 82 years, the city’s population grew by more than 1 million people. Add in commuters and tourists, and on any given day the population of Manhattan can double. Even though the TLC has allowed 1,800 new medallions to be issued since 1996, there are still fewer medallions today than in 1937.

What did anyone who wasn’t a medallion owner get out of this arrangement? Little that was good, and NYC yellow cab service was thought of as terrible.4

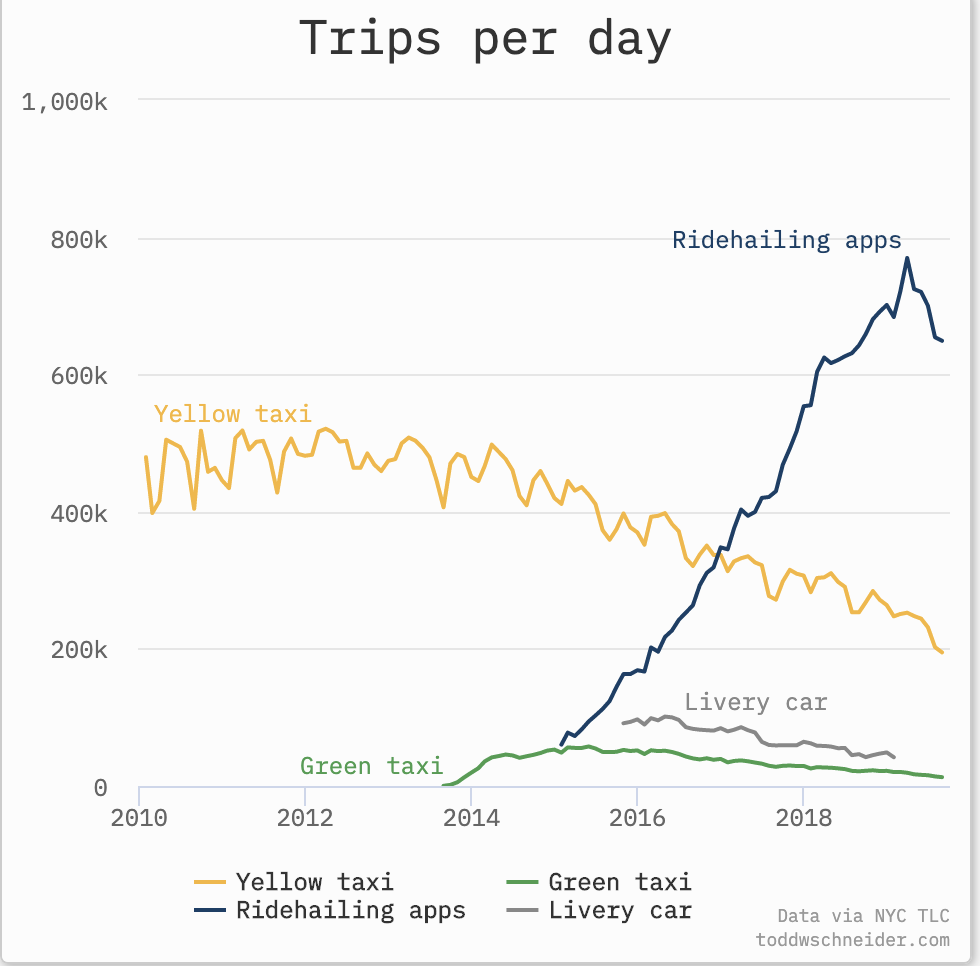

The app-based ride hailing services simply recognized this market distortion, rushing in to meet all of the pent-up demand. The result: By 2017, Uber was averaging 289,000 daily trips versus 277,000 for Yellow Cabs, and this year Lyft is on the cusp of passing Yellow Cabs as well. Together, Uber and Lyft captured 65% more rides in 2017 than cabs, and that figure surely is higher today.

Is it any surprise that market forces eventually broke the monopoly?

Soon after Uber broke the supply limitation in New York, medallion prices began to plummet. Bloomberg Businessweek reported that prices peaked in 2013 at $1.3 million per medallion. By 2015, prices had fallen more than 40 percent and by 2016, the lowest reported price was $250,000. Some transactions went for just 8% of the peak value. It is not just New York — other cities, such as Chicago, have seen similar declines.

Some people might not like it, but this is how markets work, there are always winners and losers.

Like all good rentiers, the TLC and medallion owners fought back — with new anti-market regulations to limit the growth of Uber, Lyft and app based car hailing services. Its Crony Capitalism at its finest.

Instead of asking the city to take over the loans from private individuals or companies that borrowed to buy medallions, this is a space for private equity investment funds. They have the capital and expertise to acquire these damaged assets and make something out of them. The alternative — a city bailout — would cost local taxpayers at least $1 billion, socializing the losses of 6,000 medallion owners an average debt of $600,000 each.5

Some have claimed that predatory lenders snookered medallion buyers with abusive financing. If that’s the case, courts are the proper venue for resolving those complaints. But bailing out bad investments in medallions would set a terrible precedent. It isn’t the role of the city ensure do-overs of bad business decisions.

We all would be happy to roll our worst trades onto someone else’s P&L; but socialized losses, and privatized gains is not how capitalism is supposed to work…

________________

1. 950 medallion owners have already filed for bankruptcy.

2. Biju Mathew, “Taxi!: Cabs and Capitalism in New York City,” the proposed solution was an independent panel to oversee the industry. This ushered in a new era rich in corruption and failure, marked by indictments and convictions.

3. Chicago’s smaller fleet of medallion taxis was worth $2.5 billion in 2013.

4. Monopolies in the absence of adequate regulation lead to bad economic outcomes. Consider the appalling taxi service historically offered in New York City: taxi drivers change shifts between 5 p.m. and 6 p.m., abandoning the city in the midst of rush hour, returning to the outer boroughs or even New Jersey for driver changes. The cars are often in bad shape, devoid of shock absorbers, and often filthy.

5. “The plan would have the city take over the loans from private lenders for about 25% of their original value, as some private-equity companies have done. The city’s upfront expense would be $900 million.”

Previously:

Its Not Capitalism, its Crony Capitalism (March 1, 2019)

Government Misunderstands Ride Hailing Apps (August 13, 2018)

How the TLC & Medallion Owners Created Uber (May 4, 2018)