Forecasts of the return of inflation have been greatly exaggerated.

Today, I want to discuss several “Flations,” from De-flation to Re-flation to In-flation and its bastard offspring, Hyper-inflation.

Inflation occurs when one or more factors combine to drive prices higher. Often, wage pressures raise prices for good and services, filtering into the general economy (1960s). Sometimes, the combination of a weakening dollar and rising commodity prices send input costs higher, which kicks off an inflationary spiral (1970s). Third, there are times when the cost of capital becomes so cheap it sends anything priced in dollars or debt off into an upwards spiral of (2000s).

But Inflation is not inevitable. There are numerous countervailing forces that have been at work for much of the past 50 years. The three big Deflation drivers: 1) Technology, which creates massive economies of scale, especially in digital products (e.g., Software); 2) Robotics/Automation, which efficiently create more physical goods at lower prices; and 3) Globalization and Labor Arbitrage, which sends work to lower cost regions, making goods and services less expensive.

Put into this context, Inflation is periodic, driven by specific events; Deflation is consistent, the background state of the modern economy. To fully understand this requires grasping how scarcity and abundance act as the drivers of the price of labor and goods. My suspicion is many economists who came of age during earlier eras of inflation fail to discern how the world has changed since.

Consider what this combination implies: the dominant modern world “flation” tends to be biased more towards falling than rising prices. We live in an era of Deflation, punctuated by occasional spasms of Inflation. This suggests that fears of inflation are likely to be more overstated, even with low monetary rates and high fiscal stimulus.

The net result: Forecasters have been over-estimating inflation by more than a little and hyper-inflation by more than a lot. Indeed, the Fed and most economists got this wrong in the 2000s, radically under-estimating how the novelty of ultra-low rates, high employment, and weak dollar caused prices to go higher.

Inflation was robust until the Great Financial Crisis came along; in its aftermath, inflation was (despite all too many forecasts) a no show. Persistent under-employment led to a lot of slack in the labor force, even as the US economy saw unemployment fall to below the 4% levels.

Perhaps this explains why so many economists forecast a post GFC inflation that never arrived. Post Covid, we should see hiring and lots of pent up demand and a transitory bout of modest inflation. But even that is likely to be much less of a threat than it has been in prior decades.

But not to the old school economists. Perhaps they need to reconfigure their models of what causes inflation and deflation. Being wrong for the past two decades should provide the motivation to update those models. Unfortunately, we see little evidence they are interested in changing their fundamental concept of what drives prices higher.

Milton Friedman said, “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon” — 50 years ago, in 1970. The world has changed dramatically since. I wish economists understanding of inflation would change also.

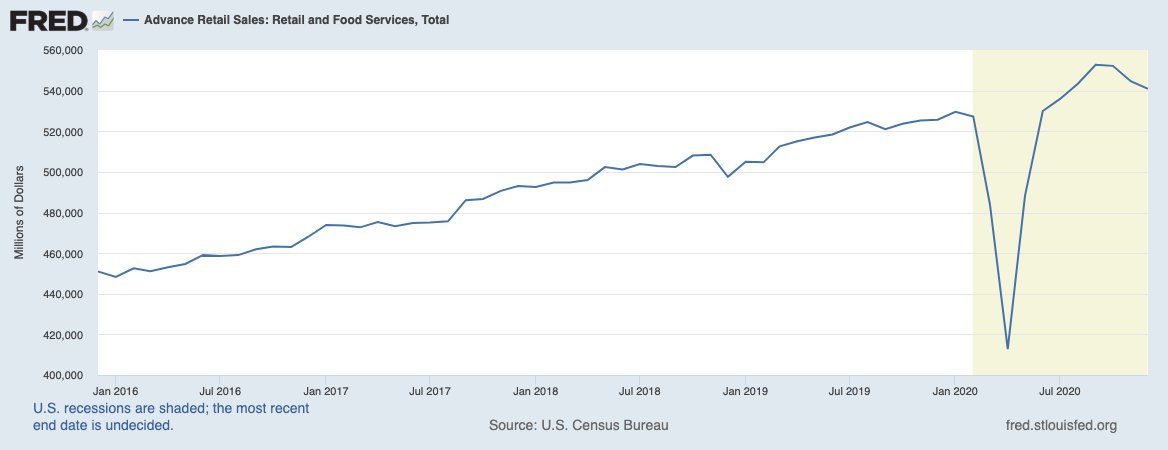

What Pent Up Demand?

Source: FRED

UPDATE: February 12 2021

This is the chart of rising inflation expectations — not inflation per se, but what people think might happen.

Its worth pointing out that people’s expectations have been mostly wrong, and even if they get this one right, inflation under 2.5% is nothing to freak out about.

Previously:

The Inflation Truther Crank Index: Confessions of an Inflation Truther (July 21, 2014)

Inflation Is Not a Problem (Yet) (June 25, 2018)

See also:

If Anyone Can Make Investors Happy, It’s Janet Yellen (Bloomberg, February 11, 2021)

Four More Reasons to Worry About U.S. Inflation (Bloomberg, February 10, 2021)