A bonus LIVE episode of Masters in Business:

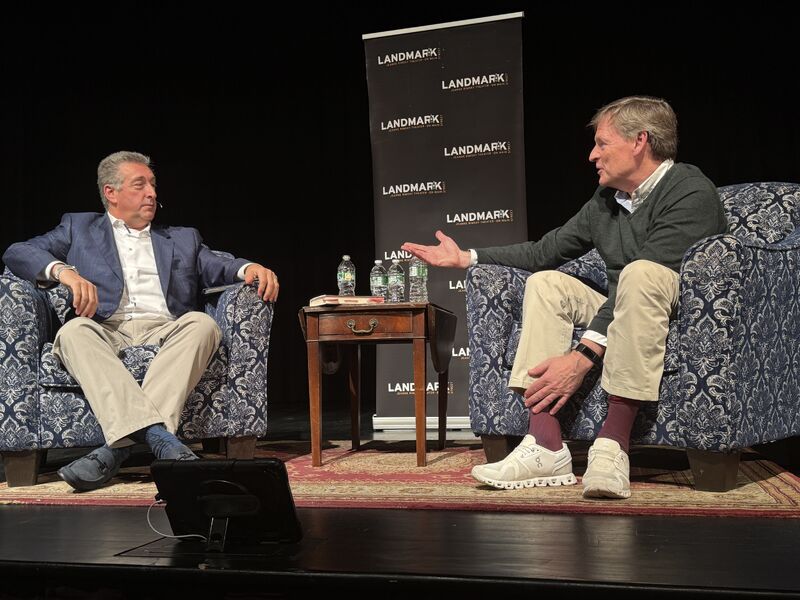

I speak with bestselling author and financial journalist Michael Lewis, live, from the Landmark Theater in Port Washington, NY.

Our wide-ranging, 90-minute conversation covered the full arc of his career, from “Liar’s Poker” to this year’s “Who is Government.” The informative – and at times hilarious – conversation included his experiences turning Moneyball into a film (including on-set hijinks from Brad Pitt), how his career as a writer evolved, and what he is working on next.

You can stream and download our full conversation, including any podcast extras, on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, YouTube, and Bloomberg. All of our earlier podcasts on your favorite pod hosts can be found here.

You DO NOT want to miss this fun, rollicking live episode of Masters in Business.

Transcript below…

Michael Lewis LIVE Transcript:

This is Masters in Business on Bloomberg radio

Barry Ritholtz: Another Masters in Business Live, this time with Michael Lewis.

I’ve been fortunate to interview the poet laureate of finance, I don’t know, maybe a dozen times, 10 times over the years I’ve interviewed him after each of the last few books.

And, I’ve interviewed him live at a couple of conferences and events. I’ve had dinners with him. I’ve gotten drunk with him at a bar late at night. Imagine the greatest storyteller of your generation, and then sitting at a bar and having a couple of drinks with him; it’s every bit as spectacular as you would imagine.

So when I read that his new book was coming out. I said, “Hey, if you’re interested in speaking to a small group at a local theater, I’d be happy to to set that up.” And, his book PR people said, “Great.”

So at the Main Street Theater in Port Washington to a crowd of just 300 people, he regaled us with stories for 90 minutes. You’ll hear almost no me in this, because my job was just to give him a nudge and then stay the hell out of his way. You could tell the audience loved it. It was so much fun, there were plenty of I had never heard before, listen for the story about Billy Bean and the f-bomb.

It really is special . . .I thought this was a blast, and I think you will also. With no further ado, Michael Lewis on his new book, “Who is government” and his career as a writer.

~~~

Barry Ritholtz: Welcome, Michael.

Michael Lewis: It’s a pleasure. Thank you for having me.

Barry Ritholtz:Welcome to the North Shore of Long Island to Gatsby, Long Island.

Michael Lewis: I’ve seen none of it. It was dark and rainy. Is it?

Barry Ritholtz: Let’s start out, how, how you doing? How’s the book tour going?

Michael Lewis: So it’s called Who is Government?

Barry Ritholtz: Who is government?

Michael Lewis:You said, “What is government?”

Barry Ritholtz: Yeah, the same thing. Who is government?

Michael Lewis:And, it’s an odd, it’s an odd. If we’re gonna be honest here. There are books and there are book-like objects. And this is closer to a book like Object, because I didn’t write the whole thing. I wrote, I wrote a third of it. Mm-hmm. I, I love it. But I, but I got, I am, I have six other writers that I hired to do this with me.

I’m answering this the way I’m answering your question. The book tours, it’s normally my least favorite part of what I do for a living. It’s, and, and I don’t know why that is. I just don’t because it’s a slog. It’s, it’s, I don’t like being on tv. But you gotta do that. I don’t, the the business of presenting yourself this way is so different from the business of writing the book that it’s jarring in, in the first place and then the worst thing happens.

You start to like it. And, and then you get, you get going back in to like, being a writer book is jarring. But, but the, the thing that is usually a, a problem is that, you know, you’re kind of on the line, you know, it’s your book, it’s just you’re out there alone. Now, if people say it sucks, I can just say it’s the other people who are responsible.

And so I feel it’s kind ofit’s kind of a, it’s kind of a pleasure, this one compared to the others going out and talking about it.

Barry Ritholtz: So I’ve only seen you with some of the other authors once or twice. You were on some show with, Kamua Bell and I don’t think you were, I haven’t seen you with any of the other co-authors.

Michael Lewis:Did you see the, did you see it was Morning Joe with Kamal Bell? (Yeah.) All right, so Kamal be, is a six foot, five inch, 300, 250 pound black man. Right? And, and he shows up at Morning Joe in a sweatshirt that says immigrants aren’t criminals, but the president is one. And, and, and, and, and they say. They say you can’t wear that on tv.

Joe is not there. He’s remote and so they, they try to find something that will fit Kamal, be nothing will fit Kamal be Is that why it was inside out? Is that what he did? No. What he did, no, it gets worse than that. They then tried to get him to flip it around and it looked ridiculous. Then they put it right side, the right side out again and they put black tape over just the bottom part of that.

And then when they, by the time we got, he got finished, we’d lost our segment. They, they, they, they’d run out of time and Joe was heading off to Dr. There’s another hour Joe was headed off to drive his kid to school and they called him and said that we can’t have him on because you know, we can’t figure out what do with the sweatshirt.

And Joe Interceded and said, have him wear the sweatshirt. He can make sure everybody can read it. And put him on and Wow. And what was, but what was really weird about it is that though Joe was comfortable making that statement on his, on his show, n none of the authorities in the actual studio were, and so they frame Kamau, it’s like this giant head and you can’t see anything.

And the whole time he’s talking, he keeps going, he goes, he’s going like this with a sweatshirt. [I saw that}. Did you see that? Yes. Yeah. No, it was, it’s incredibly distracting. I was trying to have a conversation and he’s, this man is doing this thing with his sweatshirt. But yes, mostly it’s been, I mean, I, I’ve done some stuff with some of the co-authors, mostly stage stuff.

So I’ve been on stage one way or another in one city or another with all of them or each of them. but most of the, most of the other stuff, the TV stuff I’ve had to do on my own.

Barry Ritholtz: So I want to get to this book in a minute, but first I wanna set the stage with the arc of the two prior books [’cause] I that are related to this. Well, exactly. That’s what I’m teeing up. I’m just trying, don’t get ahead of me. Just trying to help. So the premonition was how the US really did a mediocre job. During the pandemic, you focused on charity Dean and the pandemic emergency response team and the mess they had to clean up.

I’m curious how that book led to the Fifth Risk, which was the book, that was the predecessor to this. So I’m gonna have to help you. Go ahead. The fifth risk is before this. Before the, before the premonition. It goes Fifth Risk Premonition this

Barry Ritholtz: Then, withdrawn. Okay. So, but, so the Fifth Risk is the predecessor book to this.

Michael Lewis:Yes. How did that lead to this book? Yeah, so that, there we go. I’m sorry, I got the order wrong. Yeah, yeah. Sorry about that. And, and your wife, Wendy, is here somewhere in the front row. I’m so sorry you’re feeling poorly, but thanks. Thank you for coming,

Barry Ritholtz: By the way, wouldn’t be the first time you’ve embarrassed me in public and we, we could save that conversation for later. [Okay. But, okay.] How did those books lead to this book?

Michael Lewis: So, this is how it happens. It’s really simple and it is all none. It all seems worthy from a distance. Like I have some great political or social purpose. In fact, it’s all literary opportunism. Trump is elected the first time. Trump fires a day after his election his transition team and enterprise, I didn’t know existed until I read he’d fired it. But it was 550 people that Chris Christie assembled for him to go into the government and receive from the Obama administration, the briefings that a thousand people in the Obama administration had by law, spent six months preparing.

So given it’s Obama, it’s probably like the best academic course in the history of the government, on the government. And, Trump fired the people who were gonna go listen to this. Like they just said, we don’t need. And he told Chris Christie — Chris Christie told me, he said — we’re so smart, that it’ll take us an hour to figure out how the government works. We don’t need that.

And I thought this is like a great comic premise that, that, that I can go and wander around the government, get all these briefings that he didn’t bother to get, and the reader will feel rightly like they know more about the government than the president and the president’s supposed to be running it.

And the, that book, it was, it’s, it was a series again, it was more of a book like object. It was three long Vanity Fair pieces plus a piece, that, so it just happened to work as when you glued ’em all together. But I picked intentionally the departments that nobody paid any attention to. So not state or treasury or anything like that. I picked commerce, agriculture, and energy. Ones where if I turn to my neighbors in Berkeley, all of whom have, are inflicting their political opinions upon me constantly, if I say, what does the Commerce Department do? They, I get a blank stare. They have no idea. And I found in those places one really good material, like all of the places sort of like matter.

There’s stuff going on in each of them that’s really, really, really important. but unbelievable characters. Can I tell you about one character?

Barry Ritholtz: Sure. but I don’t want before you, [I don’t want you got, your train is on the track and I don’t want to interrupt]. Well, you’re, you’re just skipping the best part of how did you get access to all these people?

You kinda left out if there’s this giant transition team that was supposed to be for the incoming Trump administration and he fired them all,how did, how did you get access to this?

Michael Lewis:He fired the ones who were going in to listen to the briefing. So you just, the briefings were still there in some ways. Like in some places, like the Turkey sandwiches were still moldering and, you know, that they had prepared, they had figured out what drinks they might want. It was all, all set up.

Barry Ritholtz: So you reach out to,who?

Michael Lewis: I reach out to, in the first place, people inside the energy department, I, I got some names of officials in the energy department, started with the outgoing Obama people, but quickly got into the civil service.

Cause the civil service does the briefings. I mean, they’re the ones who are. I mean, in the energy department, for example, running a $50 billion cleanup of the nuclear waste left behind in eastern Washington from the building of the atom bomb in the 1940s, it’s still going on. You know, there’s like that thing, there’s, there are all these things.

There’s a nuclear arsenal. I went and I went and met with the people who managed the nuclear arsal arsenal, and they couldn’t tell me the, there was classified stuff, but they could tell me a lot. And their attitude was, we’re so grateful someone’s come to listen. Like, like we did all this work to like explain how it all works.

And, and, and I started with energy, but not I, you know, it could have gone anywhere. But I started with energy because I don’t know if you remember, but Rick Perry was [Oops!] Oops. Was Donald Trump’s pick for Secretary of Energy? ’cause he, ’cause he, I mean, in Trump’s mind it looks like oil Texas, right?

Looks good on television. But Rick Perry had called for the elimination of the energy department when he was running for president. And that’s a little awkward. You’re gonna go be running this place when you said it shouldn’t exist. [Tough first day]. But he had no idea what was in it. And the minute he found out it was in it, he went to the senate, his senate hearings, and said, God, I’m really sorry, con, I like, I was wrong. You shouldn’t get rid of this place.

So I went there because he was, because I just thought this is like, this is the reductio ad absurdum of this, this ignorance. And the pieces, the pieces really worked. Like they, I mean, the material was so good, but what happened as I crept my way through the obscure parts of the federal government, I kept meeting incredible people — I was not, I did not have a picture in my head of who who the federal employee was.

What I was meeting was very different from what I had imagined. And so the book comes out, it sells half a million copies and it’s glued together, Vanity Fair articles, which told you that there is a interest in a civics lesson. Which is what it was kind of. And I got the problem of having it write it as you will soon have, and afterward to the paperback, it comes out a year later.

And I thought, you know, I kind of, although it’s worked so far, I’m, it bothers me that I’ve not done a deep dive into one of these people. ’cause the people, they’re, they were, they were mission driven, usually very expert in some very narrow thing, completely incapable of telling their own stories. walled off by political people, so they weren’t allowed to tell their own stories, oblivious to the sense any themselves as characters.

But, but that’s great. Characters don’t know their characters. I mean, the fact that you don’t know you’re a character makes you an even better character. And I thought, I’m just gonna pick one of these people. So who. Now when I had this problem, Trump had then shut down the government. It was, it was the first, it was the government shutdown of 18 and 19, early nine.

It was early 2019, and he had furloughed 60% of the civilian workforce sent them home as ential workers who without pay. So I got, there is an organization in Washington called the Partnership for Public Service that tries and fails over and over to get positive attention shined upon these federal workers and they give an award called the Sammy Award to people who do something good in the civil service.

It’s been going on for, this has been going on for two decades and still no one pays it any attention, but there’ve been lots of nominations for those awards, thousands of them. So I cross referenced like anybody who’s been nominated for a Sammy and that was like 8,000 people or something with who’s been furloughed.

And the list came back and it was like 5,000. It was some huge list. And I thought, what the hell am I gonna do with this? It was alphabetized. I just took the first name on the list. “Arthur A. Allen.” He was the first one on the list, and I found his phone number. I called him up and said, I wanna come talk to you about what you do. And I didn’t really know what he did.

So this is the beginning of this book, because what happens with Arthur A. Allen, I go see him. He is the, the lone oceanographer in the Coast Guard Search and Rescue Division. He’s been at it for 30 something years. And he, he pretty quickly is, tells me that like Americans have this unbelievable ability to get lost at sea, to just like, we just do it better than anybody else.

And so the Coast Guard just rescue is constantly occupied. He figures out some, a few years into his career, he witnesses a tragedy. He’s, he’s out in the field. He’s at the Chesapeake Pace Station. A storm summer storm comes outta nowhere. The Coast Guard is pulling people off the Chesapeake Bay. They discovered that they got everybody, but there’s one boat missing and it’s got a, a woman who was Art’s wife’s age and a little girl who was his daughter’s age.

And they’re, they, they know because they know when the storm kicked up, when the boat likely capsized, they were on a sailboat. And they, so they know and they know where they were when they capsize, kind of. But what they don’t know, presuming that they’re on, on the upside down boat, is how that upside down sailboat drifts at sea. Objects drift differently. Like if you’re in an inner tube, it’s, you’ll move in the ocean differently than if you’re in an upside-down sailboat than you would if you were on a life raft, you know, and so on.

And they find the girl and the mother dead the next morning and Art says, that’s never gonna happen again.

When he is telling me this story, like. What he’s done with his career, a bunch of things. But he has basically invented the science of studying objects drifting at sea. And he’s told me, and at this point in our interactions, I’d been, I was there a couple days before, I said like, why did you even bother to do this?

And he goes over to his bookshelf and he pulls this yellow newspaper article from the Norfolk, whatever, about this mother and child. And he starts to cry. He said that, that could have been my wife, that could have been my child. And when I saw when that happened, I said, it’s never gonna happen again.

So he starts studying how objects drift and throwing them into the Long Island Sound from he lives in Connecticut and he classifies a couple of hundred objects, the results they, and reduces their drift patterns to mathematical formula.

Like 10 days after the Coast Guard gets his formula, 350 pound man, this is a very American thing to do. I remember runs out of his window on a cruise ship in the carnival on a Carnival Cruise line, cruise 80 miles east of Miami and isn’t discovered missing for like several hours. And he does it at night

Because they have cameras on the side of the boat. They know when, when he, they can go back and say, oh, this is when he went off. But Art had studied fat man at sea and

Barry Ritholtz: That’s a thing? Fat guy’s floating at sea?

Michael Lewis: He had a fat, he actually studied large and smaller people and he had fat guy at sea and which will turn out to come turn out to come in very handy in future years.

But this is the first time. Fat guy at sea who goes over off a boat and isn’t discovered missing for a few hours in human history. He’s dead. Like, it’s like finding a person at sea is like finding a soccer ball in the state of Connecticut. You just, it’s, it’s almost impossible. They pluck this dude out of the water like seven hours because he’s fat.

He can live forever. You know? You not, no hypothermia. The risk is someone so’s gonna swallow it, but that’s it. And it’s really a huge advantage to have that fat. And they pluck him out and he’s sort of like, kind of cool. He’s like, like, he’s not panicked or anything. He’s just floating at sea. But they, he, he, they pull him out and there are all these articles about like how great the search and rescue people are who pulled him out of the sea.

No one asks, how’d they find him?

The Coast Guard themselves are shocked, like, how well this worked. And this goes on. I mean, I taught, interviewed another fat guy who fell off another boat in, in, in the Pacific. And I, who was saved miraculously after like eight hours. And I said, like, how do you think they found you? And he said, what, how, what saved you? Or something?

And he says, when I was floating in the ocean, I accepted Jesus Christ as my Lord and Savior, and that’s why I was saved.

And I said, no, no, no, no, no, you’re saved. ’cause of Arthur A. Allen, you know, that’s who saved you. But nobody paid, had paid any attention to this dude and what he had done.

So I spent a few days with him listening to the, I mean, the whole intellectual stuff about how what he did, how he did what he did. It was riveting. But the motive, like this I’m not gonna let another American die because they, we don’t know this. He fixes the problem. Thousands of people are alive today around the world because of what he’s done.

He’s been honored by other countries, Taiwan and Australia. But we pay him no attention. So I gather my stuff to go write my, the end of my book and, and I’m on my way back to the airport.

And he, after I’ve spent the time with him, and he calls cell, this is the moment this book starts, he calls my cell and he says, Hey, you are a writer. And I said, I’ve been there with my notepad. You know, I’ve been like, I’ve been, I know I had said something when I called him, but I said, and he said, he said, man, he said, I was just talking to my son. He says, like, you’ve published books and like one of the books became movie. A movie. And he goes, are you gonna, are you gonna write about this? Are you gonna write about me?

And I said, yeah, Art. I mean, why do you think I flew across country and spent three days interviewing your wife and children and all the rest? He said, I just thought you were really interested in how objects drift.

And, and, and, and, and this is, this, this, this is your One, an inessential worker. Two, your public servant, your civil servant. They have no sense. Like they deserve any kind of attention. The stories that come out of them are amazing. And I thought, man, I should have done it the first time. I should have been diving into these people’s lives. So the next time, if I ever come back, I’m gonna come back focused on the people.

And when I, I was on a hiking trail with David Shipley, who was once until recently, the opinion editor of the Washington Post. And he had space and he had money and his, and he, we could write as long as we wanted in his pages, he said, I said, let me, I’m worried that if I go do this, it’ll just be either, “Oh, this is Michael Lewis’, take on the federal government, or I made it up.”

Or whatever, like, whatever. Whenever people don’t want to hear the message, it’s very easy to come after the writer and try to undermine the whatever’s in the,

Barry Ritholtz: Is that why you picked six other writers? That’s what I did. I said to shield the accusation of bias?

Michael Lewis: also to get a bit, a little bit of a bigger kind of sample, like not gonna tell ’em what to do. I didn’t even tell ’em why I, what, what I was gonna do. And I’ve done two of these big profiles in here and the material is as good as ever. but I said, we’re just gonna, you just go into federal government and wander around and find a story. And six out of the five out of the six other six did much of what, basically what I did, they found unbelievable character studies, individuals doing things that were just to shock them.

One, he’s, he’s a wonderful writer, John Lanchester, English writer. decided instead that his character was the consumer price index, which is a challenge. but he actually makes it work. It’s ’cause it is an amazing achievement. But he, he writes, so he, he went off the reservation a bit.

Barry Ritholtz: I’ll push back on the characterization when we come to that chapter. Right, right. ’cause I have a different spin on that. Oh. But, but let’s talk about some of the chapters in here, starting with Ronald Walters of the National Cemetery. I can’t start with myself.

Michael Lewis:You wanna start that way? I mean, other, other people’s. I edited it, but other people, other people. I give you such a sh I will tell you.

Barry Ritholtz: So you wanna start with the coal mines? Let’s start with No, no, I don’t wanna, I I’ve already muscled you around too much.

Michael Lewis: Feel free to muscle. I’m the fish and you’re the fisherman. Okay. You’re supposed to be landing me. but it’s, um. Ronald Walters. So this is the one, the one writer who came to me after I had employed them all and said, is there anything on your cutting room floor that you would like to have written about that you didn’t write?

I said, well, that’s funny you say, but yes, it’s Ronald Walters. Casey Sepp, who’s a wonderful New Yorker writer. She, she wrote a book about Harper Lee called Furious Hours. And we met because I reviewed that book for the New York Times so favorably she got in touch and sent me toffee boxes of toffee.

But, but when we became friends, Ronald Walters, this I’ll be brief because I didn’t get to know him. You know, I’m just read, I’m reading it like you, but what it intrigued me, Ronald Walters is in the Veterans Administration. I think he’s the only one who still has his job securely, but he, he may be insecure now too, but he took over these National Cemeteries Association, the cemeteries that where we bury veterans.

And there are like 55 of these things around the country, like 4 million veterans are buried in them. They’re burying them. It’s at an astonishing rate and it’s sort of like, it’s a sacred duty. It’s where we bury our war dead. It’s where we bury people who’ve made great sacrifice for the country. And it’s a tribute to the country that we take it seriously, that the Veterans Administration even has this program.

But when he inherited it, it was struggling in its, it’s a weird way to put it, consumer satisfaction. The consumers in this case were the loved ones of the people who were being buried. And he took it from, and we know this because the University of Michigan measures customer satisfaction across the society. It’s all institute big institutions, not just it’s private sector, but also government agencies. And it was kind of like most of the government agencies, kind of high sixties. It was like a mediocre thing.

And in a period of a decade, Ronald Wal Walters took it. To being not just the enterprise in the United States government that had the highest customer satisfaction, but the enterprise in the entire country. More than Costco, more than Amazon or FedEx or the other ones that people like it.

And no one knew his name. No one knew how he did it or why. And I, I had, when I was fiddling around with picking someone to write the, afterward for the Fifth Risk, I’d heard his story. And I almost, I tried calling and actually they didn’t even return my calls. The veteran administration wouldn’t talk to me.

So, so it was there and I said, go, go find that out, out about that. And so she writes about how he did what he did. It’s an,

Barry Ritholtz: It’s an absolutely beautiful chapter. It actually made me cry. Did it? It’s the only, only chapter in the book that, that brings tears to your eyes. Let’s talk about coal mining and how dangerous it is. Let’s talk about your first chapter.

Michael Lewis:So, so another, so this is. I mean, it, it’s so unusual to find such a rich vein of material that is basically unexplored, that is so predictably yielding gold. And this, so this is, this is number two for me. I’ve done our Allen, I’ve done the, the agencies.

II’m gonna go pick another person. So I went back to, kind of did it the way I did it before. I got a list of the people who were nominated for Sammy’s awards this year or last year. And this list was almost 600 people. And because it’s, they don’t know what they’re doing. I mean, they know what they’re doing in some ways, but they just don’t know how to create interest in people.

All these, this list of the people who’ve been nominated for the award, it just said their name and what they’d done. And you looked at the accomplishment and they were often amazing. It was like, you know, you know, it, it, but it would, it would never say how they did it, you know, “Cured cancer” but that was it kind of thing. John Smith at the National Institute of Health Cure Cancer, period. End of story.

I was going through this listening. It was all just cold-blooded, you know, it was just like, until I get to Christopher Marx, solve the problem of coal mine roofs falling in on coal miners, which has killed 50,000 American coal miners in the last century, leading cause of death in the most dangerous occupation in the country.

The occupation is so dangerous that it was more dangerous being in a coal mine than being in the Vietnam War. That’s how, that’s how dangerous it was. But the last sentence said he was a former coal miner. They finally gave me some, something to think about. And so I looked and I thought, man, there has got to be a story here.

I mean, I’m thinking grew up in West Virginia, like Dad was injured or killed, or see, you know, there, there’s some, how this person gets out and does this. So I had spun this whole tale up in my head. and I find his number, and again, like our ally, he’s lives in Pittsburgh. I call him, I cold call him. In this case, he knew who I was.

He’d read Moneyball and it turned out that he thought of himself as money balling coal mines. But that’s a whole separate thing. but, but, he, he, he, I say, I just wanna hear, I just wanna hear your story. Like give me the, the 10 minute version. I’m gonna give you the five minutes of the 10 minute version because it hooked me.

He says, I grew up in Princeton, New Jersey, and my dad was a professor at the university. And I thought, oh, like my whole movie is different, you know, I don’t know what the movie is, but this, this not. And I thought, oh, my interest just went. And then he started to tell me, he says, if you looked at just a little bit, you’d find my dad was kind of famous.

Robert Marks was the name. And Robert Marks had been brought, brought to Princeton without a PhD. To help Princeton. He had devised a mechanism for stress testing. He was stress testing fighter planes for the Navy and the Air Force before they built them. He take the design, build a little model, and he had this, this complicated way of just testing whether or not this design was going to actually work in practice.

And Princeton had brought ’em in to test little nuclear reactors they wanted to build to see if it was gonna crack. And Robert Mark one day was teaching an engineering class at Princeton. When an undergraduate walks in from an art history class and says, this device you have, could you use it to like figure out what’s holding gothic cathedrals up?

Because we just, they just told us that no one understands how these, the roofs of gothic cathedrals don’t collapse. There’s no records left by the builders, then they’re built over a century. No one knows what’s decorative, what’s actually holding the weight. And he said, yeah. And he became famous because he became the guy who figured out how they built the gothic cathedrals and what was keeping them up.

What was keeping the roof up. So that’s Robert, that’s the dad. Chris is telling me this in the first 15 minutes I’m talking to him. He says, so that was my dad. He said, I, I had a problem with my dad’s life. It was the Vietnam War. I got kind of radicalized. I thought I, I saw it wasn’t Princeton kids who were fighting and dying.

And that really bothered me. And he said, I, he, he said, he started throwing words around the house like bourgeois. And, and pretty soon he said, I’m not, he could go have gone to Harvard or Princeton. I’m not gonna do that. I’m gonna go join the working class. So he breaks with his dad, big break. He goes on the road.

He works in an auto factory, works in the UPS plant, and finally ends up with several fellow radicals in a coal mine in West Virginia. The other three radicals all quit at the end of the first day. It’s that brutal. He finds it interesting. Why he finds it interesting is still a bit of a mystery, but he stays in the mine for a year and almost dies twice that he sees how dangerous it is.

He crawls out of the mine, goes and gets a PhD, an undergraduate and a PhD at Penn State in, in rock engineering, and begins the process of figuring out, he, there’s all this data that the US government has co collected on. They’ve, they’ve observed the problem. It’s a bit like the CDC does with the disease that they’ve observed the problem without actually trying to stop the problem.

So they have all this data on when roofs fell and what the conditions were. He just, he starts to study it. And over a career, a really, really interesting career figures out how to stop this from happening and stops it from happening. So he is telling me this on the phone and, I did gimme all the details of his work, but, and, and I stop him and I say, oh.

So you rebelled against your dad and then you just went and had your dad’s career. He was, he figured out how to keep the, what was keeping up the rules of gothic cathedrals and you figured out how to keep the rules of coal mines up. And, I mean, this is someone I’ve just started talking to on the phone.

He gets outraged. It’s like bull***, you know, like I’m calling, you know, that has nothing to, I had nothing to do What I did, had nothing to do with my father’s career. we, we have nothing in common. Completely different thing if that’s your theory, like go away kind of thing. And I said, just seems a natural observation.

So so two things. when I, I went and spent a lot of time with him. We rolled around West Virginia. He took me into coal mines and he doesn’t mention till like the third day that, oh, you know, it was funny. I were, you reconciled. When did, how did you reconcile with your dad? And I asked him, ’cause they had become reconciled before his dad died.

And he said it was gradually, he said, but there was this moment he said, I. The National Cathedral, the federal government thought the National Cathedral in Washington might be falling down. This was in the year 2000. One of the towers was subsiding faster than the other. And, they didn’t know why. So they called his dad to test to see how the load was moving through the National Cathedral.

And the dad figured out that his stuff didn’t work because whatever was going on, it wasn’t above ground, it was below ground. So he called his son, and his son had the stuff to go figure out what was going on below ground. And together they wrote a paper about how the National Cathedral, how it was, what was gonna happen.

And we didn’t have to worry about it falling down, but they studied it together and put everybody’s minds to rest. Now, when you have that to navigate too, in a story, you got a story. I mean, it’s just like that. And, and so Art Allen had the Yellow Wing newspaper. Christopher Marks had the, had the, the dad.

I met, but I gotta say I’ve met lots of people in like the Storm center and the National Weather Service who lost loved ones to tornadoes or that, that this instrument, the federal government is filled with all of all this purpose, all these things that, that it’s where the problems of the private sector doesn’t wanna deal with go, you know, you know, it’s like if there’s no money to be made in it, but we’ve decided as a society we wanna address it.

That’s where the, that’s where we, that’s what we use to address it. Who, who is attracted to these problems? People who have a particular interest in this problem for whatever reason. And that quality, like caring about the problem, it’s outside yourself. I’m gonna fix the problem, tends to come from a deep place.

And that’s where literature comes from. You know, it’s the, the, the motives of the characters are, are, are in our government. These are rich and interesting people with rich and interesting backstories and, and. you know, e every time you kind of start scratching at one, you get at this.

BR: So, so let’s address that a bit. I wanna discuss your process a little bit, which I’m fascinated by. You once said to Malcolm Gladwell at the 92nd Street Y “the subjects choose me. I don’t go looking for books. The stories wander into my life and they get to the point where they can’t not be written. The stories kind of find me, a relationship develops between me and the story.”

ML: I have no choice. That’s true. So, so expound on that a bit. You want the three minute or the five minute version? Whatever you’re comfortable with. Alright. I mean, this goes back to who I am. I mean, I’m basically. I’m a new, I grew up in New Orleans, was raised to be a decorative object. I was raised to, what does that mean?

Not useful. Okay. Like, like nobody around me did anything useful and no one planned to, and hence you end up on Wall Street there. No. Yeah. Well that’s funny. But, but, but there’s a certain charm you acquire on the streets of New Orleans that are very useful when you’re trying to sell a bond. but it’s that, but yes, so a lot of New Orleans make their way to Wall Street.

They do quite well on Wall Street. You get the gift of gab kind of thing. But, you learn to tell a story, which is very valuable in the financial markets and also valuable, very valuable to writers but I, I’m basically lazy, like that is true. Um. You know, it’s, it’s it’s core in me. Like the working part of me has been added on somehow.

But the deep me, I would just sit around, scratch myself for the rest of my life.

BR: If, if you, you’ve written 14 books, how is that lazy?

ML: This is, I’m, I’m not lying. This is this. I’m telling you the truth. You’re just gonna have to figure out, you gotta make sense of it. Okay. this is God’s truth.

My father, when I, from the age of about seven to the age of when I was 18, had me persuaded that there was Latin, we had a coat of arms. Lewis, Lewis, and there was always a Latin under it. He persuaded me that what that Latin said was you translated. Was, do as little as possible. And that unwillingly for it is better to see, receive a slight reprimand than to perform an arduous task.

My father raised me to be lazy, you know? I mean, that, that he was like, don’t try, don’t, don’t sweat it. You’re working too hard. It was the, it was, this is the environment I was raised in and I took to it. but, but you didn’t, you, but I did. Up to a point. Every book you’ve written, you embed yourself now in unfamiliar places, learn.

It’s also true. You learn. It’s also No, it’s true. It’s, I’m curious. I got that too. I’m actually curious. I see something and I want to know about it and, and it happens a lot. It just happens a lot. And so it’s a, with pleasure, I find I pursue a curiosity. I ask like, curiosity. Why are the Oakland A’s winning baseball games with no money?

Like, how is that possible? That’s a beginning, that’s a curiosity. I, and so I go to the trouble, but most people have that thought and go, eh, who? Who knows? And then fun. And, and you, you spend, you spend weeks and weeks and wait years. Wait, so, so, so, so it is not, it is true that I do the work. It is true. I eventually do the work, but I do from a place of deep laziness.

It’s deep. It’s like that, it is, I get curious. I start to get involved. I realize, oh my God, this is, look at this story. And it is, it is got to, it really does have to rise to the level in my mind that this story is so important and it’s delusional. Like is any story that important? But it’s, the story is so important that I have an obligation to do it.

So now I, now I have to do it because I have an obligation. I make myself feel that way. And when I feel that way, then I’m off. then, then I forget about the laziness and I do the work.

BR: So you have this incredible knack of finding yourself in the right place at the right time. Before everybody else figures out this is what’s so this is an incredibly lucky thing.

ML: Okay, so I mean, but it’s, I’ll give you that. This one’s Lucky

BR: Liar’s Poker. You’re there early in the rise of Wall Street. It was working. Okay. You were working Moneyball. No one had any idea what was going on with Saber Metrics and how this scrappy little broke team was able to put together a competitive run;

Going Infinite. You embed with FTX and Sam Bankman Fried a year. That was kind of cool. That was a year before, right, but you after, but that was also after the, I didn’t know that was happening. Oh, oh, you didn’t know that was happening. And then the whole Undoing Project with Danny Kahneman, who just coincidentally lived down the street from you.

You have this ridiculous knack to finding yourself at the head of a wave that’s about to crash over society. I mean, once or twice as dumb luck. How do you do it six times in a row? That’s not exactly luck.

ML: I think it is; I mean, in, in that, I, you know, you and I, so he’s just published a book too, “How Not to Invest.” It’s really good. And, and you, you say 18 different ways in the course of this book, how skeptical you are of the ability to predict the future. [Sure.] I am too. Okay. Everybody wants you to predict the future and you just shouldn’t do it because it’s just, you know, you can’t, who knows where the stock wants, but you’re always skating to where the puck’s gonna be.

BR: Explain that.

ML: It’s maybe, I think the puck is just coming to where I happen to be. That, that it, that. So, so I don’t think I, I really think it. Sam Bankman Freed lands on my front porch after someone asked me to just interview him and evaluate him from, I didn’t go looking for him. He walked up and I said, this is interesting.

I’m gonna follow, I’m just gonna follow him around. this, I had, I had this nagging sense. That I’ve left all this gold in the mind. I still feel that way. There’s gold in that mind still. And I left the gold in the mind. Let’s go back there and get it and bring some friends and they can have some of the gold too.

And, the, I mean, I had no idea that Trump was going to do what he’s done to the government. No, none. I, I did have a sense like he didn’t care about it. That he was going to just completely try to gut it. I had no sense. so in every case I know the, how much accident there was. I will say, if I were trying to make the case that I have, I know something that other people don’t or there’s something about me that leads to being a little ahead of the curve.

I’d only say that. The best, the closest thing to the best way to predict the future is just pay attention to the present. That you pay closer attention to the present than other people are. You. You see, it’s the, the, the future is there. And so it is, I, I do pay attention to the present. I observe. And, and, and I also, so this gets back to the laziness, that, that when you’re lazy, it’s an actor.

It’s not necessarily a bad thing to be a little lazy. Amos Tversky, my character in the Undoing project had a great line, which I, which, which I tell every kid who asked for advice, I just repeat it. He says, “People waste years of their lives not being willing to waste hours of their lives,” that people get so worked up about making, being busy, moving their career up.

They don’t let anything, they don’t let things in. They, they, they’re like always achieving. And if you just back away and let the world come into you, it, it’s, that’s a helpful approach to a writer also. If, if you’re a little lazy, like you would rather basically not be doing anything, it takes a level of interest to move you.

Like I know a lot of writers who just go, they can always find something to write about because they know, they feel like they have to be writing, so they just force it. before I sit down and bother to put a word on the page, I’ve gotten. So I’ve had to get so excited about it to offset the natural tendency not to do anything.

And so that it, it’s, it’s like the material is leaping over higher hurdles mm-hmm. To get to the place with me that I wanna write about it.

So maybe that’s, that has something to do with this.

BR: Can, can I float a theory to you?

ML: Sure. I think it’s gonna be bulls***. You can do it.

BR: Malcolm Gladwell’s Grand Unified theory of Michael Lewis books is biblical allegories.

ML: Right. That’s bullshit.

BR: Yeah. That is bullshit, right? Daniel And the Lions then is Liars Poker. The Blindside is Good. Samaritan David and Goliath. Moneyball. Like, you’re not doing biblical allegories.

ML: No, I mean you can, the truth is you can find almost any, you can map almost any story onto the Bible.

BR: Right? Right. But, but here’s what’s not: Every Michael Lewis book features a character and the archetype, Michael Lewis character, quirky outsiders pushing against the grain ’cause they’ve discovered some interesting insight or truth or previously unknown thing that is against the consensus. And then they apply that to their field and either they make a lot of money shorting stocks or they save fat guys who’ve fallen off of cruise ships.

ML: Yeah. That’s, those are the same characters, but every, who’s that character and liar’s poker?

BR: You!

ML: You think that’s me?

BR: Well, you show flashes of you. Yeah. It was your first book. Yeah. So yeah. We’ll cut you a little slack. Yeah, but you know, in fact, let, let’s talk about Liar’s Poker.

Yeah. So, so, so we, we, we did a podcast on the 30th anniversary. [Right.] You had to go reread it, not just reread the book, but read it out loud for the audio version.

ML: Yeah. I hadn’t reread it since I wrote it.

BR: So, so first, what was that experience like?

ML: Awful. I mean, I don’t know if you’ve ever gone back and, I was 26 when I wrote that, and I’d never written anything. I mean, I’d written letters to my mother and a few articles in The Economist and I mean, it was a, I was just work, I was really raw. And I,

BR: but still there are flashes of the future. Michael Lewis, the writer throughout, Hey, listen, first of all, for a first time book, it was great,

ML: but you know what’s funny?

BR: And you were 26 so you could cut yourself some slack.

ML: So there were some things, some things I noticed. One is there was just general infelicity, but I noticed that whenever I thought I was being funny, I wasn’t funny. And whenever I didn’t, I was like, oh, that’s funny. But I didn’t know it was funny, you know, it was embarrassing, you know, there was, I was, I thought I, there were lines that were clearly like, designed to get people to laugh and then I shouldn’t have been doing it.

that, and there were structure. I, so it was, I, but, but yeah, I, I mean, I’m feel finally towards it, it got my, it launched my career.

BR: I’m going back and let me also, now I’m back.

ML: I’m still stuck on your theory,

BR: So, but let me just point out that you wrote that book while you were working full-time at Solomon Brothers, you were doing this nights and weekends, right? At least that’s when you started sketching this, this wasn’t Michael Lewis the full-time writer, correct?

ML: Right.

BR: So when you look back at that, you gotta give yourself a little slack, not bad for a first attempt.

ML: No, no, no. I, no, it wasn’t, it’s fine. It’s not bad for a first book. I agree. It’s not bad for a first book, but the, I, when I think about when your description of what of my books, the quirky outsider the line.

I think of it this way. Because they’re not like Billy Bean’s, not quirky. Billy Bean’s like the coolest guy in the room when he walks into a room. He is, yes. He’s got, we’re all quirky, like underneath. We all have little things, things going on that are, we’re all above average. All we’re all neurotic or a little, we all have stuff.

BR: But, your characters have a lot of stuff, Mike.

ML: Sometimes they’d have a lot of stuff, but they, the, the thing, what I think of, I think of it as more as I get excited by someone who could teach me. Mm-hmm. And all my characters are, are teaching me something about the world. And now the kind of person who’s teaching you something, something about the world often is someone who has been challenging the world.

So that’s true too. They’re often in kind of conflict with the world. But what’s attracting me to them, I never think, oh, quirky great. Or I never think that Brad Tama is not quirky. He’s a nice Canadian boy. Mm-hmm. And Flash boys. Flash boys that he is. The least quirky person who ever carried a book, he is normal.

He’s like as normal as they, they get. And there’s some stuff there with what there is, is nice Canadian boy collides with Wall Street and, and is upset when he sees what’s going on.

BR: But he figures out a way around and, and figures out, yes, figures out that the, he’s the least quirky of all your characters, but let, let’s stick with Moneyball.

But, but how, how did you gain access to the A’s? How did they, you know, grant you keys to the kingdom?

ML: This often happens too, that you have a question. And the question is equally interesting to the subject. So I called Billy Bean, went and go see him. I said, I just look, it doesn’t make any sense. You’re spending one fifth with the Yankees are spending, how can you be competing if this market is efficient? The Yankees should be buying all the best baseball players and you would just lose all the time.

And he said, “No one has asked me that question.”

It’s what I think about all the time. The sports, he’s just covered by sports writers and the sports. The baseball writers at the time paid no attention to the financial disparities. They weren’t thinking of the money on the field. And that’s all they thought about was the front office, was the money on the field. So he was interested in the question in the first place. And also, I didn’t tell him I was writing a book. I told him I thought I didn’t know what I was gonna write. Maybe a little magazine piece, maybe nothing.

And it got more and more interesting and I disguised how interesting I was. And when I just divulged, you know, two months into it that I was thinking about writing a book. It was too late. He couldn’t get rid of me. I knew too much. but, but there was, and, and I had found ways to insinuate myself into, into their lives.

I mean. You, you, this is like, how do you make yourself, how you,

BR: How do you get them to let you hang around?

ML: That’s the important thing. You’ve gotta hang around. You gotta be kind of in the, you know, just, just they, they forget you’re there. Kind of hang around. So that was the trick there. Did I ever tell, have I told you when that book became a book?

BR: No.

ML: Like when I came home at late at night and I said, wrote my publisher and said, this is gonna freak you out, but I’m gonna write a sports book. I was, I was, I was in the locker room of the Oakland A’s interviewing, telling the players. I was interviewing the players one by one and telling them what the, why they were, they were playing first base or why they were the lead off hitter.

They, they, they had no idea front office, no idea. The, a front office regarded it as a science experiment and they were the lab rats and it just confused their lab rats if you told them what the experiment was. And they told me like, don’t talk to ’em about it. They just thought they won’t handle it well. And, but the players were really interested.

So I was, they, I was welcome in the clubhouse and, and they were coming out of the showers. I was waiting for my guy to talk to him and I, for the first time I saw the Oakland A’s naked, and it was such a disgusting sight. It was, it was, it was like, it was just, I mean, not,

BR: not ripped professional athletes.

ML: It was like they had cankles and they had, they were all fat. They look a beer league team. They looked like, and I had the thought, which I relayed to the front office. It was like, if you line those naked bodies up against a wall and asked anybody what they did for a living, nobody would guess professional athletes that they, they would guess like, you know, wall Street guys, they could, they could be Wall Street guys, they could be accountants, they could be flight attendants, they could be, but not, not professional athletes.

And the front office said, “It’s funny you say that because we are aware of how unattractive they are without their clothes on. ” that, that, that, that they, they said that. And the, and there’s a, that “We get excited. When they’re unattractive without their clothes on. And they don’t look, when they don’t look right because the market, we, we are evaluating them blind. It’s just we’re valuing, we are looking for performance statistics. And when we find the player whose statistics are, are promising, but they look wrong, we know why the market’s misvaluation them. They’re misbeing mis-valued because of the way they look.”

And I remember, I just, it blew my mind. I remember going, driving home and thinking, oh my God, this is when you have a duty to write it. Like never mind baseball. Think of this as a corporation, and they got these employees, they’ve been doing the same thing for a hundred years. Millions of people are watching them stats attached to every move they make on the job. If those people can be misvalued because of the misvalued, because of the way they look, who can’t be? Everybody can be.

So this is a universal story. It’s that feeling like this is a universal story. And, and so I got very excited and I wrote my publisher note and said, sorry, here it comes. I’m gonna be writing a book called Moneyball.

And now the flip side of this is, none of my subjects ever know what I’m doing. They really don’t. They know I’m hanging around, but they, I mean, Oakland saw me. I spent a week with the Blue Jays. I spent days with the Rangers, I spent days with the Mariners. I spent fifth time with the Red Sox, and I had to do that to know that they were special, like, know that nobody else was doing this. And and so, but, so from their point of view, it was like, what’s he doing? Like Billy,

ML: And when, so when Billy Bean got the book, and my subjects only get the book when everybody else gets the book, you know, I, I don’t want him, I don’t want him bothering me. and he got the book. He was furious. It was like

BR: He was angry because you let out the secret.

ML: Two things, two things. One was like, since when am I, the main character could have told me. You know, it’s that kind of thing. It’s like, I, I’m not, I was not, I didn’t sign up for this kind of thing. But, but second thing he says, I thought he was gonna be pissed off because I, I had revealed their secrets.

That’s what I was worried. I was worried that was the betrayal. He says he’s, he’s on the phone, he’s like, incoherent. And I said, what is bothering you? And he said, you have me saying all the time. And I said, you do say all the time. What am I supposed to do there? And he said, “You don’t understand. My mother’s gonna be so upset.”

And, and, and, and I said, you’re mom, you know, like, really, it’s like a sigh of relief if that’s what we’re worried about here. Low level problem. And, and turned out not to be a low level problem. She was furious. She, she is still furious and she’s angry at me. she’s still angry at me. I swear to God. She’s angry about it.

And, but. But I said to Billy, I said, I started laughing. I started said like, if I was so worried you were gonna be angry with me for, for, for stitching together this narrative that revealed all your secrets. I found out as much as I could and I put as much of it in the book as I could, and it’s gonna blow your competitive advantage. I thought that’s what you were angry about.

And this is pause on the end, other end of the line. And he says, “You don’t think anybody in baseball is gonna read your book?” He says, he’s like, they’re always gonna read your book. They don’t, they don’t know how to read. He said, but he said like, we’ve been doing this for years. Nobody’s asked a question and [wow]. And he was kind of right. He was right about that. It was too narrow. He was right that nobody ever reads a book who thinks they know what they’re doing and changes their mind. Like no GM at the time was gonna say, oh, I learned something from this book, or, oh, we’ve been doing it the wrong way.

BR: Well, didn’t the GM of Red Sox eventually come?

ML: Well, at no. While I was working on the book, John Henry had just bought the Red Sox, [the hedge fund manager], and he was saying, he actually said, what do I gotta do to prevent you from writing this book? Because he said, we’re about to do this here. And he wanted to hire Billy.

And I became, it was kind of fun. I remember doing this on payphones in the airport. I became, they weren’t allowed to negotiate [talk, right]. So they negotiate through me. So I, I, I helped organize Billy’s contract with the Red Sox and and Billy was gonna go and then change his mind last minute I and Theo Epstein becomes the GM of the Red Sox.

Mm-hmm. See, Theo was trying to hire Billy too. He was part of the group inside, and, but the rest is history. And Theo leads the Red Sox to Victory, and Billy Bean has written out of that story but the, the Red Sox were about to do it. New owner, like new owner who had background in finance. So he gets this, he gets statistics and data and all that.

What happened was other owners read the book, like the head of Goldman Sachs at the time I know, talked to the, the owner of the Mets and said, “You’re being ripped off by your own management.” Like they don’t know what they’re doing. And o at the ownership level, they started to change things. So that, that’s, that was how the change happened.

It would’ve happened anyway. What would’ve happened if I hadn’t read the written the book is the Red Sox would’ve done this. They would’ve won the World Series using. Sabremetrics or statistics mm-hmm. They would’ve gotten total credit for revolutionizing the sport. And no one and Billy Bean would’ve been a footnote. Hmm. that, that’s, that’s what would’ve happened.

BR: Of, of all your books, that became a movie. That’s probably my favorite film version. [Is it?] what was that process like watching? Do you just essentially sign the papers and that’s it? Or did they retain you for script consulting or anything like that?

ML: So what happens is, what happens is, for sure the movie people would rather the author be dead. There’s no question. Like, all you can do from their point of view is cause trouble like complain or give advice.

And I was aware of this quite early. Like, I know they, they don’t care what, I think it was really clear they didn’t care, but they were trying to pretend like they’d sort of cared. And this was Blindside actually was the first one.

And I thought. It, but they wouldn’t leave me alone. Like it, I couldn’t just say, here, really? Just give me the money. I’ll give you the book and whatever you do. No. Whatever you do [See at the opening!] Yeah. See at the opening. And if it just, just make it don’t suck. And, and, and it’s on you. If it does.

’cause it’s your, it’s gonna be, it’s not my movie. It’s your movie. And they refuse to accept that blunt relationship, I think. ’cause they don’t believe that. I actually think that. And so what happens is they pretend to be interested.

BR: They don’t know you’re lazy.

ML: They don’t know I’m lazy. I really, they’re like, they pretend to be interested in what I think I have to pretend to be, believe they’re interested in what I think we have this false interaction where I give them advice and they ignore it all.

And, but out of this, some really lovely friendships have sprung like it’s a social relationship. So I’m friends with all the directors who’ve made the movies really friends. And some of the actors are still in my life. And like Jonah Hill will just call me up outta the blue and say, “I got a problem. I’m gonna just talk this through” and that kind of thing.

And. And that that is gr That’s been great. Can I tell you a story about the Moneyball movie? Sure. It’s, it’s the Moneyball movie. Was this sort of,

BR: You guys wanna hear a story about Moneyball, right? [Yeah]

ML: So the Moneyball movie. So Billy being, in addition to being pissed off at me because I had him saying all the time he was, he was put, I really admire the guy.

He was put in a really difficult position. The book puts him in opposition to his industry. He knows something everybody else does, and all the other GMs hate him. All of a sudden, when he is, he didn’t deserve this. And he, but he, instead of, instead of throwing me under the bus, he just fought. He said, there’s not nothing in the book that’s not true.

So you wanna, you wanna fight about it, come fight. And he’s brave. He’s basically a very brave person. However, it was so unpleasant. The book I. A among, among the most un, maybe the most unpleasant publication in that it all of baseball was angry, really angry. And, he said, he called me one day, he says like, Sony Pictures is trying to buy my life rights to make a movie. And I says, I just wanna tell you I’m not doing this. Like, I, I didn’t want the book. I don’t want a movie. I don’t need this.

I said,” Billy, you don’t understand. They never make the movie. They just give you money for your rights that I’ve sold. I dunno, a dozen magazine articles, five books, money just comes outta Hollywood and they never make anything.”

‘Cause they hadn’t made anything at that point.

And I, when I gave the list of like the amounts I’d raked in from Hollywood for doing absolutely nothing, he sort of said like, this is free. And I said, yeah, it’s free. And so he took a bunch of money for his life rights. It was an option that renewed every 18 months and every 18 months he called me, he goes, “You’re a genius. Like, this is unbelievable. You’re right. They’re not gonna make this movie.” It goes on for years, you know, like seven years.

But, and, and then one day he calls me up and says, you, he said, he said, Brad Pitt just called me and he says he’s coming over to the house and my wife is putting on makeup and the babysitter’s going home to get a dress.

And, and it was like he said, “You said this wouldn’t happen” I remember he was like, you said this wouldn’t happen. And I said, I don’t know what to tell you. Like I’m, I’m a little shocked this is happening.

Flash forward, I don’t know, a year, six months, they’re shooting in the Oakland Coliseum. And, I’d gone to a set, the set a couple of times.

This was the cool thing I brought my kids because they had 8,000 extras in the Oakland Coss and they’d gotten body doubles for the 2002 Kansas City Royals and Oakland A’s. So like Barty Zito looked more than like Barry Zito, than Barry Zito. And they’re replaying this game and they’re moving the 8,000 people around the Colise to make it look like it’s full, and it’s a great drama.

Before I go over, to see this, they call me and say, Sony calls me and says “Billy Bean is refusing to have anything to do with anybody. Like, he’s not visited the set. He let Brad Pitt come to his house once, and that was it. And that he’s like, everybody’s worried. He’s just angry about this. Could you get him down? His office is at the stadium. Could he just walk down and shake a couple of hands and make everybody feel good?”

And so I, I called him, I said, Billy, like, it’s not that big a deal. Just come on over. And he said, “Are you gonna be there?”

And I said, yeah. He says, okay, then I’ll come, I’ll come and I just spend 10 minutes.

I don’t want them to think I’m into it though. So it was like, okay, they know you’re not into it. Come on over. Shakes some hands. So we get there, I’m there on the field, and he comes walking out and this production, young male production assistant comes running outta left field and he’s got the headgear and he’s got a, he’s got a notepad and he comes running up to Billy and says, Mr. Bean, Mr. Bean, you, “You’ve been my hero ever since I read your book. I just want, I won’t tell you how you changed my life.” And Billy’s like, it’s not my book. He, he wrote the book, he points to me, he goes, no, this is your book the guy’s. So it’s like weird. He says, will you just please sign my book?

And Billy says, alright, I’ll sign your book.

And so he opens the notepad and there were two Billy beans in the major leagues at the same time. Wow. And they both played at, in the same outfield on the Tigers. And I think the twins, that was weird. They were both there on the field at the same time. And the other Billy Bean was gay, and he came out of the closet and wrote a memoir and it called like “Hitting from the other side of the plate.”

And so this guy has, has the gay Billy Bean’s memoir. And, and Billy, the, the straight Billy Bean is, he’s like, there’s nothing good is happening right now. It’s like, he’s like, “What do I say? What do I do?” I’m not, you don’t say I’m not gay. You don’t say you don’t, there’s nothing you can do in this situation.

And I look over and in the a’s dugout Brad Pitt’s rolling around, he set the whole thing up. He had Sony pictures call me to talk Billy to come into the field so he could play this. He had thought of this joke and so he could play this joke on Billy, on Billy Bean and it worked. It really worked.

BR: So that is a great story.

Before we open this up for questions, I want to ask one or two more questions, including another story you told about a name confusion when you had spent some time in Israel, with Danny Kahneman.

ML: Oh, that’s funny. And you, you, similar story you go to wasn’t nearly as good a story is this. So Danny Kahneman, the great Israeli psychologist who’s one of the main characters of the Undoing Project,

BR: One of the two main characters.

ML: Yeah. He was one of the two main characters. And he and Amos both had done a lot of work with the Israeli military. He had, he had Moneyballed Israeli, Israeli troops to determine who should be a, an officer. And you devise whole these, these metrics so you can measure it rather than just do it by an interview.

So he was there very early. The reason I even wrote that book is I came back to that book after Moneyball. ’cause when Moneyball comes out, Richard Thaler economist, Cass Sunstein, his writing partner, reviewed it and said. “Michael Lewis has written a really interesting story, but he doesn’t know what it’s about.”

And he, they said “It’s a case study in the work of Kahneman & Tversky. That’s how I even heard that these guys existed. Anyway, I go to Israel, we’re going to the military base where Danny did that money balling work for the, for the Israeli army. And we get, we get there and they are 400 of the best looking young women I’ve ever seen. And what, just waiting for us, like waiting in a mob behind the gates when we come through and they look at us and they just kinda like melt away.

And at first I thought, wow, Danny’s got it going on, you know, I mean it’s like what he, they’re here for Danny and it turns out there’s an Israeli underwear model model named Michael Lewis.

And, and he’s got like, he’s got like unbelievable abs. And so they, they’d seen Danny Kahneman coming with Michael Lewis and they thought it was the underwear model.

BR: Unbelievable. So, so there’s a question I want to, I’ve been wanting to ask you for a while and I just never. Get to it, so I’m gonna force it early.

You, you have, I know you have all these stories that are half told and all these things that are future projects. I’m always curious if there was a loose thread in a story that you said, I really wanna pull that and see what happens in some of the books you’ve published, but you haven’t gotten to

ML: What do you mean?

BR: What characters, what lines of, of thought that you kind of briefly go over and sort of say in the back of your head, gee, I should really circle back to that. That looks really interesting, but just haven’t gotten around to, from any of your books. ’cause I know you have dozens and dozens of things that you’ve started, new. You have all your research and folders and stuff, right? Is there any

ML: You mean what do I have on the back burner that might go on the front burner? No.

BR: Well that’s another question. It’s, it’s what kinda loose thread has been out and about from some of the books you’ve written that you just,

ML: You thinking something?

BR: No, nothing in particular. This is, this was, literally a, a Twitter question. I said, gimme some questions for, oh, this was the only one that I thought was half decent.

ML: I thought you were asking me about, I was wrong. No, no, no. But it’s funny because I don’t, no, I have books that I, I they, they’re books that I started and stopped ’cause they didn’t work.

There’s book, a book that got away that would’ve been a shot at a masterpiece. But the subject tossed me out ’cause I made the mistake of writing something in a magazine about him before I wrote the book.

BR: What was that?

ML: George Soros? It was 1990. And Soros was interested in me for a bunch of reasons. He, I had. Soros had somebody he really admired as a money manager. Like he was Soros. As Soros. His name was Neils Taub. He ran Jacob Rothschild’s money in London and he was, he was, he’s the smartest person I’ve ever met in the financial markets about the financial markets he had. Just that he had, you know how Soros has those jungle instincts?

He had them times two and older guy, he took me under his wing when I was at Solomon Brothers, I cold called him and I said, basically, I know you’re, I know that there’s no reason you wanna talk to me. I’ve just arrived. I’m 24. I said, I’m a new guy here. Can I take you out to breakfast? And something about the interaction caused him to say, sure, you can take me out to breakfast.

And we went out to breakfast and he said, you’re not gonna try to, if as long as you don’t try to tell me anything, sell me anything. Pretend you know something, I’ll do my business through you. And for the next two years. Over the next two years, he became the second biggest customer at Solomon Brothers. And I didn’t never have to do anything. I just picked up the phone

I would describe to him like what I’m seeing on the trading floor. I describe what I was seeing in the markets, but I never said, you should do this ’cause it would’ve been folly. And he appreciated that.

And he told Soros about me when I left to write “Liars Poker.” And so Soros was very receptive to me. And he took me on a private trip, you know, when the Berlin Wall fell, he built all these institutes for democracy around Eastern Europe. He took me on a private trip through the, the, these places. And there was a book to do about both his fear about the threats to democracy, which seem very prescient right now.

And, like this isn’t forever. These places don’t, they have to learn democracy and we have to help them. And what he was doing in his, in the financial markets and he was gonna let me write about both and like an idiot. I then I wrote, because I was at the New Republic, I wrote for the New Republic, a piece about the trip.

And it was not rude about him. It was, what I thought of him. But I did make fun of his writing, like the all the theories. He has all these theories about why, how markets work, [Reflexivity?] yeah. All that. This intellectualizing, which is, it’s, he’s a jungle animal. And it’s like, he layers on top of it a complicated explanation. And he was so vain about his philosophy that he was really irritated when someone didn’t take it seriously.

And that was, it didn’t wanna see me again. And that was the, that was the one huge one. I’ll never make that a mistake again. It was gold, the material, and no one else was gonna get it. And no one did. No one wrote the book, the book never got written. And that book could be a, could have been a very valuable book.

But I have that, I have those kind of things. I don’t have, and I have, I think I, I’m not gonna talk about what they are, but I think I know what the next two books are. I think I know what I’m about to go do. Um. But I don’t have anything. I don’t have anything where I think, oh, oh, I wished I’d written, if I wanted to do it, I’d go do it. You know? I sold Moneyball as two books. I thought the second book was going to be about the kids they drafted that year using algorithms. And I spent two years in the minor leagues chasing around after these guys.

BR: No, go.

ML: I, two years I was in uniform as a midland rock hound in Midland, Texas, and kept shagging fly balls before the game. Like I put a no go, it’s just all notes in a under my office. Yeah. No, go.

BR: So, you know, I always come with like four hours worth of questions. Yep. But what I’d like to tell how many did, how many, how many did we not get to

ML: Oh, three quarters.

BR: Yeah. But it doesn’t matter. I wanna bring the house lights up.

ML: You never expect me to talk so much.

BR: My job’s to give you a nudge and get out of the way. Okay. So I, I think I, I mostly accomplish what I wanted to. Yep. Why don’t we bring up the house lights are up and let’s see. If there are any questions from the audience, one back here.

Yeah. I’m not gonna, just say, say your name and it’s, it’s hard to see you. So listen. And where are you from? We’ll, because Michael’s from California. We’ll, we’ll give him, a Long Island geography lesson. Go ahead.

Audience: hi, Mr. Lewis. my name’s Andrew Ucci, huge fan of yours. all your books and your podcast against the rules as well. I’m from just up the street, so very, very convenient commute. I have a question for you, related to “Losers, the road to any place, but the White House”, one of your, I believe, criminally underrated books.

Can you expand upon your relationship with John McCain as well as, what you think he means to American politics?

ML: What a question. Great question. I never get asked about John McCain, but if you ask me what the most influential thing I ever wrote was. Yeah, I might say the first thing I wrote about John McCain.

I met John McCain. I, so I was co I was assigned to cover the 96 Presidential campaign for the New Republic.

I was learning my craft. I’d written Liar’s Poker, but I had not, I mean, I’d not, I’d never written for a school newspaper, no English teacher ever thought I was worth more than a C, you know, I was just like, there was no, I had no background for this. And the New Republic at the time was filled with the most talented collection of writers I’ve ever seen in one place. And editors.

And the editor at the time was Andrew Sullivan and Andrews ship me off to just go do what I would do on the road. And I got in a car and I never got out of it. I was all over the country for the next nine months. And, It quickly became clear that the 96 presidential campaign was the most boring presidential campaign in human history. And around Bob Dole and Bill Clinton were armies of communications people who were gonna make sure you never saw anything interesting and

So I just started writing about what was interesting rather than what I was supposed to write about. And I, and I started to pick up characters who resonated with me and with, in small groups of voters.

So I made the, I flipped it, I made minor characters, the main characters, and put Dole and Clinton in the background. And it really worked as a series in the New Republic. And then I, it brought out as a book.

But in the course of this, I was in a air, you know, a terminal in Spartanburg, South Carolina at 11 o’clock at night told the Dole campaign was gonna land to pick me up.

And the question was why would they do that? And why they would do that was McCain was in the same terminal. And I recognized him, vaguely, it was just the two of us. And they came over to, said “Hi.” And we started talking and he was at that time disgraced. He was part of the, one of the Keating five, he’d been involved in the, in the savings and loan scandal. He had barely won his reelection.

He was just different than any politician I met. He was like real, and I just started getting interested in him. And then I learned his story about how he had been in, he’d been held in prison and his limbs had been broken during the Vietnam War and that they were torturing him. This was the amazing thing.

The Vietnamese were torturing John McCain to get him to accept early release. They were trying to let him go, because his father was an admiral and they thought they could undermine the morale of the American troops if they started letting in the fancy people’s kids out of prisoner of war camp.

And he, and so he got beat up over and over because he refused to go home before the people who had been, who had been captured before him. Now it, so the piece that create, I. I found it by just, I was just hanging with him. ’cause I was interested in him. I didn’t know where it was gonna lead. He didn’t really belong in a book about the nine six presidential campaign, except he was dole’s most popular surrogate.

But hold that was, that to one side.

He lets slip that he has this relationship and it was, it came, came out very naturally. This guy, I was coming over to his office. This other guy was coming over to his office named David Ihin. And David Ipshin was a Vietnam War protestor who went with Jane Fonda to Hanoi and piped anti-war propaganda into John McCain’s cell.

And Ipshin had later in life, things had changed since that time. And McCain had been celebrated for his war heroism and Ipshin had become kind of blacklisted by American politics because of his involvement, even though McCain kind of admired his conviction. And McCain saw,

Ipshin ends up going to work for Clinton. And then I. If someone came out with a story about how Ian had done this with Jane Fonda and Clinton was about to kind of release him, and McCain got involved and told Clinton, like, “You keep him on and I’m gonna get up and give a speech about this guy on the, on the senate floor about he’s my friend.”

They developed a relationship. And so I wrote the story about the, this relationship between the war protestor and the war hero. And, it was 3000 words in the New Republic, which ends up in this book, “Losers” and McCain at that moment was sort of like untouchable by the journalist. Nobody paid was paying much attention, and he was a little disgraced

Overnight, everybody wanted to write the same story and, and he got his relationship to the rest of the world, to the media in Washington just changed. He would, he, we, we became friends and he, he let me in on this process.

He was like, “That piece changed my life.” And, and it made it possible for him to go become the candidate he became.

It was an, it was amazing watching what a little piece of journalism can do. And it was very mo a very moving story. The, the wrinkle to it was, when I wrote the story, Chen was dying. He was dying of cancer. He was on his deathbed. So Chen was telling me about how what John McCain had done from him, from, for him, from his deathbed.