I grew up in the generation of latchkey kids: Both parents worked; you came home from school, fixed yourself a quick bite, then ran off to the playground for some stick- or b-ball. We weren’t wildly overscheduled; we didn’t have 20 hours a week of school events, after-school activities, and projects. We were (mostly) on our own.

This led to a generation of parents who recognized the risks all this unsupervised play created. The results were three simple rules that every kid who grew up in the 1960s, 70s, and even 80s had to learn:

1. Make sure your parents knew where you were going to be after school;

2. Be home for dinner (hands washed and at the table) by 6pm;

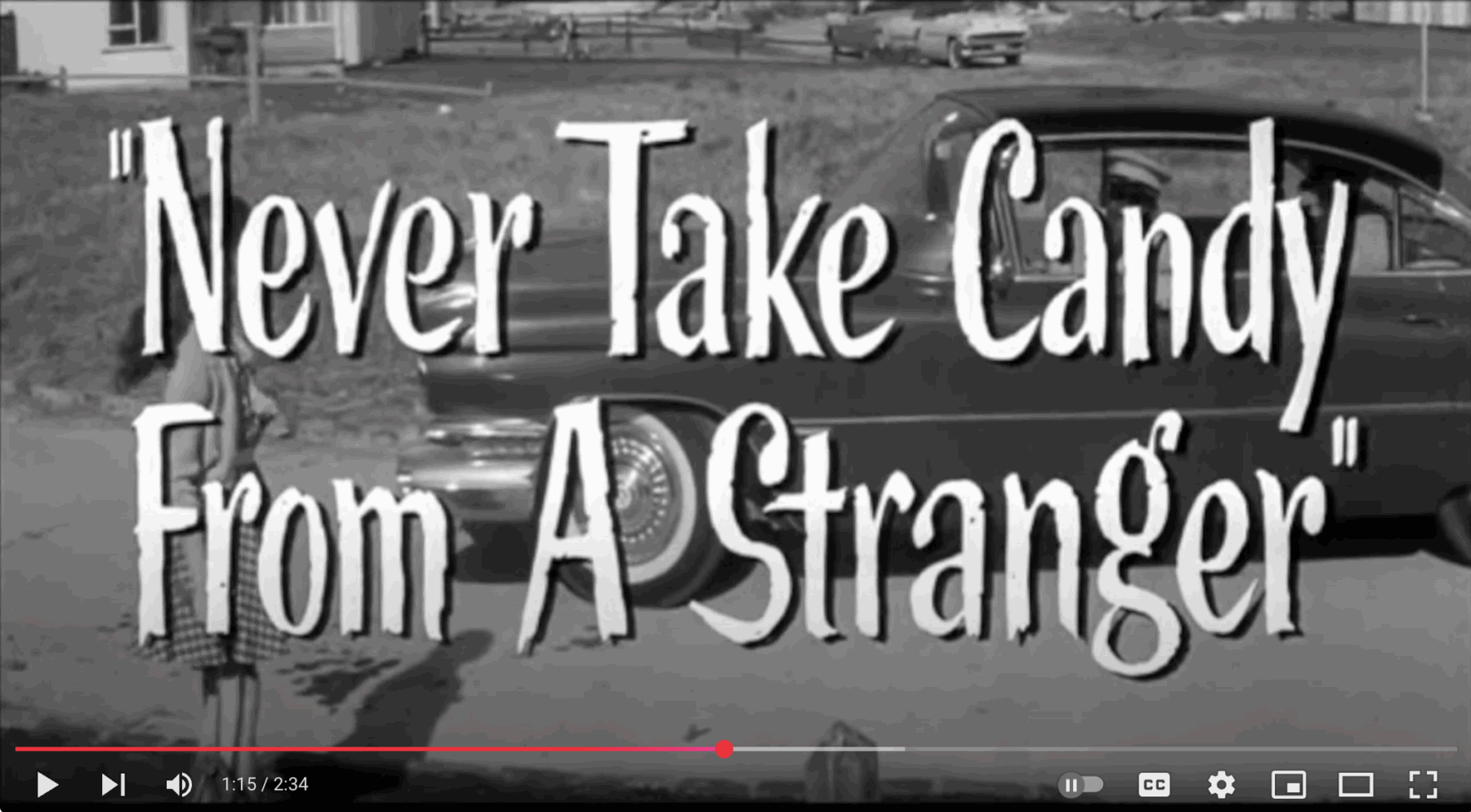

3. Never take candy from strangers.1

That was it!

Every other rule was a variation on this theme. Whether you had a sleepover at Brian’s house or were playing hoops with Marc, Chuck, and Ritchie, you had to leave a note or a message at home and/or your parents’ workplace as to what you were doing that day. Dinner was the same time every day, and if you were late, there was gonna be hell to pay for it.

Technology has rendered the rules 1 and 2 obsolete: Parents know exactly where their kids are to within a few feet, courtesy of the tracking apps on their phones. Texting lets them know precisely when they are coming home. But that third rule…

Today, I want to discuss why you should never take candy from strangers. It was true when I was 12 years old, developing a decent pull-up jump shot and studying for my bar mitzvah. It’s true today, perhaps more so. It’s true, even if you are an adult, married with two kids, a dog, and a mortgage.

It’s so obvious and ingrained – at least to my generation – that it’s easy to overlook the simplicity and brilliance of this concept.

Just as your mother used to tell you not to take candy from strangers, so goes it with taking investment advice from strangers on TV, in print, weblogs, and most especially social media.

When a stranger offers you something for free, it should immediately make you ask a few questions: Who are they? What do they want? Do they have your best interests at heart? What’s in it for them? Always ask yourself: What are these people selling?

Is it a newsletter? Some wacky trading scheme or crypto scam claiming it’s gonna make you rich? “Just make 1% per day to turn $100 into millions” type nonsense.

At the very least, they are asking for your time and attention, and that has tremendous value to you as an individual. Collectively, it’s worth billions of dollars to big tech and media.

I devote at least 10 chapters in “How Not to Invest” discussing these exact topics because its that important. See:

Who do you listen to?

Prediction, Inc.?

Forecasting Chaos

What are they selling?

24/7 Financial Advice

TikTokInvestors

Gell-Mann Amnesia

Signal-to-Noise Ratio

Lose the News

Use the News: Reengineer Your Media Diet

Before you accept the investing advice from a random stranger, ask yourself if they are concerned with your comfortable retirement, buying a new house, or paying for your kids’ college. If they don’t know your zip code or tax bracket, how on earth can their advice be geared to your specific circumstances?

Of course it is not. It’s selling something, be it advertisements, investment products, newsletters, or God knows what else.

Most of what you see, hear, and read was not written with you in mind. It was created to sell a product. (This blog post, as an example, is exhorting you to buy my book). These sales pitches are not nefarious, but they have become so ubiquitous that we often overlook them.

It’s not realistic to suggest people tune everything out. However, I am making three suggestions for all consumers of financial content:

-Understand what media you are consuming;

-Make intelligent, well-informed choices;

-Prioritize quality over quantity.

I am not suggesting you become a curmudgeon who hates all they see, but rather, be a little less gullible and naïve. When I started out in the finance industry, I believed every line that came my way from every salesman, any fund manager, and each quarterly call (all filled with nonsense). I was an easy mark for any smooth-talking bullshit artist.

This is why my Mom was right to warn me not to take candy from strangers. Her advice applies equally to taking investment advice from people you don’t know and whose process, track record, and temperament you are unfamiliar with. Have they been more right than wrong? Do they have the right temperament? Lived through a few cycles? Are they worthy of your time and attention?

It took some time and some expensive losses before I figured that out.

Listen to what mom told you: Taking investment advice from people you do not know in the media in all of its forms is no different than taking candy from strangers…

Previously:

Tune Out Manage the Noise (February 20, 2025)

__________

1. There is a much longer story from 1874 about Charley Ross, the first missing child to make national headlines. It (of course) involved taking candy from strangers. A full century before my generation, and so was not exactly part of the Zeitgeist in 1974. If you want to learn more about it, see “The Kidnapping of Little Charley Ross,” Library of Congress, April 23, 2019.

For more information about “How Not to Invest” and where to buy hardcovers, e-books, and audio versions, please see this.