February marks QBAMCO’s sixth anniversary and we are grateful for the interest our views have generated. In the coming months we will be assessing the platform on which we offer investment services and our policy of distributing our views externally. Your thoughts are welcomed. This piece addresses the following issues:

Currency War – Theory & Practice: We argue one should not necessarily mistake rotating currency devaluations presently for the threat of a belligerent global currency war. Monetary authorities are likely to continue managing the timing and magnitude of discrete, coordinated relative currency weakness so that the appearance of a stable global monetary system remains intact.

Cause for Concern: While we do not expect a breakdown in global monetary oversight, we do expect fiat currency debasement to continue to mask the driver of real economic malaise and contraction – global bank de-levering; and we do expect this process to lead to a popular loss of confidence in today’s major currencies as savings instruments – perhaps beginning in the global capital markets in 2013.

Lambs to Slaughter: We do not expect an overt crash in global stock, bond and real estate markets, or one that would last very long. They are already crashing in real terms and there is a well-structured mechanism in place to support nominal pricing. Any future flight of public sponsorship would be met with central bank credit support working through bank intermediaries. For those not part of the support mechanism, however, the monetary market put does not necessarily argue in favor of investing broadly in implicitly levered financial markets.

The 1998 Committee to Save the World & Centralize Global Economic Control (and their Legacy Beards): We think the smart play is to bet with these guys and the power of their institutions.

Reasonable Contrarianism: The pain of holding an inflationary bias over the last six years has been intense, and the pain has only increased exponentially over the last two years. The good news is that we believe for the first time there are important macroeconomic events signaling a fundamental shift in the global monetary system is finally approaching. We expect discussion of Fed, ECB and BOE inflation and/or nominal GDP targeting to become louder and more frequent in 2013, and we expect markets to begin adjusting asset prices accordingly.

The Pain Trade: All the Sturm and Drang in the financial press about a revival of the US housing market is bologna. We provide a short idea.

Bad Science: On February 1, a large multinational bank published a report that called the end of the bull market in gold, claiming; “the 2011 high will prove to have been the peak for the USD gold price in this cycle.” While no one knows the future and the dollar price of gold may rise or fall, we are quite certain gold’s future path will have nothing to do with the arguments included in this report. Sadly, it was a case study in false identities leading to wayward causations and, in our view, a diametrically wrong conclusion.

The Play: We think that what will eventually (or soon) occur will be the rare occasion when return-on-savings trounces return-on-investment, implying precious metals will outperform the great majority of financial assets (except for shares in precious metals miners and natural resource producers).

*The big macro questions: Will global central banks raise rates, withdraw bank reserves or tighten credit policies in any way before the global economy experiences significant price inflation? No. Will they continue threatening to tighten? Probably. Will they continue to de-lever bank balance sheets via bank reserve creation? Absolutely. Will global central banks continue to be significant net purchasers of physical gold in 2013 and beyond? Bank on it. Will big global wealth holders convert increasing amounts of fiat currency into physical precious metals, resources and other beneficiaries of global price inflation? Highly likely. Will Western financial asset allocators figure out what all this implies for stocks and bonds in 2013? We think so, probably after a significantly higher-than-expected CPI print.

Higher global goods and service inflation is a tail event currently unforeseen by the great majority of investors and unexpressed, or expressed improperly, in the great majority of investment portfolios. And yet we see it as a lock, perhaps asserting itself in 2013.

Currency War – Theory & Practice

All seem to agree now that global monetary authorities are fully engaged in trying to protect their currencies from relative appreciation. The fundamental question remains: is there a growing likelihood of a messy sovereign “currency war” in which monetary authorities compete to beggar their neighbors or are treasury ministries (in fact, central banks) collaborating with one another to devalue their respective currencies in a sequentially, but orderly fashion? By identifying the answer we should gain insight into the nature and timing of significant changes in economic output and market valuations.

We do not think current whack-a-mole currency devaluations imply a belligerent currency war, now or in the future. Let’s follow incentives. Who does a cheap currency ultimately benefit? It theoretically helps indebted governments fund themselves with foreign investment from entities with stronger currencies, and it benefits cheap currency-based exporters deliver cheaper goods and services than exporters that report earnings in domiciles with stronger currencies. On the first score, most indebted sovereigns have come to rely predominantly on their central banks for funding (i.e., QE), rather than foreign funding.

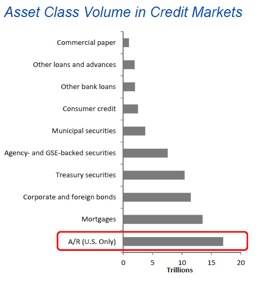

Regarding global exporters, most have set up foreign manufacturing capabilities where their products are consumed, better matching costs with revenues. Further, swap markets and trade receivables allow exporters to adequately manage their currency exposures. Everyone knows the enormity of the swaps market and it has recently come to light that trade receivables have become the largest credit market in the world (see graphic on following page). At $17 trillion, it is larger than the mortgage and corporate markets. That exporters must report earnings in their native currency by converting all margins back is a direct problem for corporate treasurers and their shareholders, not domestic employees (at least directly), which means strong currencies are not directly a problem for politicians.

For these markets to break down, the banking system would have to break down, which leads us to our final point about the potential for a global currency war. Modern currencies are created by banks and their central banks – not by governments or by domestic exporters that would benefit from cheaper currencies. This suggests a trade war is not a decision for politicians or exporters to make. Ultimately, SIFI banks control the game.

When push comes to shove, the primary mission of central banks is to keep their banking systems solvent in times of stress. (Should this effort be claimed to support economic objectives like price stability or full employment, all the better.)

A monetary food fight would risk the demise of a major currency, which, with today’s cross-levered, cross-funded bank balance sheets, would further suggest mutually-assured global bank system destruction. As bank deposits are now highly concentrated within very large SIFI banks, one major global bank failure anywhere in the world arising from one economy “winning” a currency race to the bottom would impact all global banks and, by extension, the broad perception of bank failures.When push comes to shove, the primary mission of central banks is to keep their banking systems solvent in times of stress. (Should this effort be claimed to support economic objectives like price stability or full employment, all the better.)

A monetary food fight would risk the demise of a major currency, which, with today’s cross-levered, cross-funded bank balance sheets, would further suggest mutually-assured global bank system destruction. As bank deposits are now highly concentrated within very large SIFI banks, one major global bank failure anywhere in the world arising from one economy “winning” a currency race to the bottom would impact all global banks and, by extension, the broad perception of bank failures.When push comes to shove, the primary mission of central banks is to keep their banking systems solvent in times of stress. (Should this effort be claimed to support economic objectives like price stability or full employment, all the better.)

SIFI banks are the controlling shareholders of the most influential central banks. Central bankers controlling over 75% of global GDP, in turn, gather every two months at the BIS in Basel, Switzerland to discuss and coordinate policies. We think this implies a continuation of managed, discrete currency takedowns. Beggar-thy-neighbor attitudes and rhetoric among sovereign politicos may spring up from time to time but we do not expect such attitudes in the global banking system, where it counts.

Share prices of the world’s largest banks are lagging the general market even though their revenues and earnings are soaring. Some argue the market fears that one day central banks will reverse their loose monetary conditions, in turn decreasing bank net interest margins. We do not think narrowing loan margins is a valid reason to be concerned. The cash flows of most large banks are almost certainly hedged against higher market rates, if not with each other than with their central banks. The real problem, as we see it, would be the value of their loan books, which would decline materially were rates to rise coincident with a decreasing appetite for new bank assets (loans). This fear, in itself, provides the fundamental reason not to be concerned that central banks will withdraw from the markets, letting interest rates rise, before adequately reserving SIFI banks. We expect no interest rate surprises.

So by our way of thinking there is very little risk of a belligerent global currency war. This is not to say we think central banks will stop methodically cheapening their currencies. They must continue to satisfy their principal aim of de-levering bank balance sheets to maintain bank loan book valuations. Consistent with domestic optics central banks will continue to destroy their currencies in a coordinated fashion that avoids “a global currency event.”

From a trading perspective, we speculate it is wise to play reversals at extremes of cross-rate FX ranges. The risk of major currencies breaching well-established ranges seems remote as long as major central banks work together to preserve their currency oligopoly. In light of this theory, consider the significant bounce of the EURUSD since July 2012, from 1.21 to 1.35, against almost universal sentiment believing it would see parity to the USD. Should FX traders now apply this theory to the universally accepted demise of JPYUSD?

Cause for Concern

From a longer term wealth perspective, the net result of coordinated central bank fiat currency management would be a continuation of current trends: increasing real economic malaise amid an environment of decreasing currency values. If we are right, all currencies will lose their exchange value to goods, services and assets vis-à-vis the exchange value that could be maintained by bartering goods, services and assets for each other. This implies that it is better to own stuff outright – stuff consumed today and valued tomorrow at price levels that do not rely on the future purchasing power of currency holders (a well-worn theme of ours).

As it stands, existing claims on wealth far exceed existing wealth to claim, and the decreasing absolute value of currencies is destroying perceived wealth. As an example, consider that most people are unlikely to sell their homes when: a) the bid suddenly drops by 20%, or b) selling homes at whatever clearing prices happen to prevail does not provide homeowners with incentive to act. Simply, homeowners will not provide supply at the “market price” because tomorrow, or the day after that, they think someone will offer more. The same is true for goods and service producers. They will not provide supply at the “market price” because the proceeds from such sales would bring them decreasing wealth. The more currency that global monetary authorities create, the less supply of goods and services will ultimately be created at prevailing prices.

Most economists and investors do not seem to conflate asset acquisition with goods and service consumption, yet we think they should. (Perhaps this goes a long way in explaining why most people do not presently fear goods and service inflation?) As we discussed in Macro Polo, bank system levering or de-levering first drives asset prices higher or lower and is necessarily followed by price inflation, disinflation or deflation. The growth rate of money and credit is the leading indicator of investment returns, goods and service inflation and, in (and only in) an economy expanding in real terms, aggregate wage growth. Where there is no real economic growth there can be no wage growth in combination with stable or rising employment. (Employment, like unit production, is a real variable, not a nominal one.)

Soon, we think, most people will begin to see this relationship – not because policy makers, economists or market strategists proclaim it – but because they will not be able to make ends meet. The unemployed and the employed will both experience decreasing wealth – versus their current purchasing power – regardless of the size of their wages or financial asset portfolios. Trees, real wages and the returns of stocks and bonds do not grow to the sky. Japanese, European and American nationals cannot exploit each other over time because producers lose their taste for amassing any of their currencies. We expect producers, not consumers, to exert their will by demanding money in excess of consumers’ ability to provide it. The necessary policy solution will be to put more money in the hands of consumers. That’s where goods and service inflation begins. The wealth of investors keeping cash in their home currencies, or in most financial assets denominated in those currencies, will decline in real terms regardless of which currency it is. (AAPL better use their $137 billion quickly!)

Lambs to Slaughter

With interest rates at or near zero across sovereign bond markets and with official monetary policies now targeting inflation at higher rates, one must question the soundness of investing directly in fixed-income duration products or using benchmark interest rates to justify the real relative value of tertiary bonds and equities. Most professional investors and wealth managers seem to agree that central banks and state-sponsored Interests have taken control of public market asset pricing, and yet most are ploughing ahead, abiding their investment mandates to allocate funds to public financial asset markets. Investors are no doubt clinging to hopes of past higher debt and equity (stocks and real estate) returns.

Economic policy makers are solving for higher nominal output and inflation rates and, like lambs to slaughter, investors are solving for higher nominal asset prices. These are easy missions. Raising nominal statistics and prices could not be easier; all it takes is more systemic credit and promotion. Increasing capital and real value – wealth – is the hard part.

We do not expect an overt crash in global stock, bond and real estate markets, or one that would last very long. They are already crashing in real terms and there is a well-structured mechanism in place to support nominal pricing. Any future flight of public sponsorship would be met with central bank credit support. For those not part of the support mechanism, however, this monetary market put does not necessarily argue in favor of investing broadly in implicitly levered financial markets.

We believe the wrong way to position wealth in today’s environment is the way most are presently doing so: under the presumption that financial asset markets will generally trend higher over time and that nominal price appreciation will imply wealth creation. Positive real returns cannot be generated broadly over time by unlevered investors investing in levered public capital markets and real estate. Generally, the higher credit-supported markets climb, the less a dollar of gains will buy. Serious investors should reject nominal economic and market valuation metrics.

There are only two ways current and future pensioners can maintain their wealth by participating in today’s capital markets: nimbly position assets well or abstain from investing. The former requires either being agile or concentrating wealth strategically – accurately and resolutely in capital market assets that would benefit from inflation (e.g., QB). Market abstention requires either saving in scarce forms or investing in private enterprises producing innovative or demand-inelastic goods or services.

The opposite of love is apathy, not hate; something to ponder when considering the prospects for highly levered assets like most stocks, bonds and real estate. They are not savings vehicles long-term investors should love or hate. If the ultimate objective for financial market participants is to maintain wealth relative to society, then markets should deliver (but at a cost of absolute wealth). If the ultimate goal is to increase wealth relative to society, then financial asset markets are sure to disappoint for the majority of society relying on them.

The great majority of institutional investors allocating investment capital using a conventional (ergo fiduciarally “acceptable”) investment model today, as well as individual investors and their counselors longing to be as “sophisticated” as these institutions by trying to replicate the same flawed adherence to popular markets regardless of real valuation, ensure that nominal prices will rise as real purchasing power declines.

The 1998 Committee to Save the World & Centralize Global Economic Control:

• Robert Rubin

• Alan Greenspan

• Larry Summers

And their Legacy Institutional Beards:

• Resolute central bankers

• Active trade negotiators

• Calculating politicians

• Extrapolating academics

We think the smart play is to bet with these guys and the power of their institutions.

Reasonable Contrarianism

The pain of holding an inflationary bias over the last six years has been intense, and the pain has only increased exponentially over the last two years. The good news is that we believe for the first time there are important macroeconomic events signaling that a fundamental shift in the global monetary system is finally approaching. These events should be very supportive to precious metals and precious metal miners. First, it is important to be mindful of the following realities:

• The de-levering process is the dynamic that drives gold higher and it has not yet begun. Leverage has merely migrated from banks and households to governments and central banks.

• Bank credit and broad measures of money are not expanding to the extent required to support relative leveraged asset pricing.

• Central banks are reported to be substantial net buyers of gold.

• A higher gold price ultimately is a global policy solution, once gold is owned ubiquitously by official accounts (and banks are further de-levered).

Japan’s economy was able to grow nominally from 2000 to 2007 through its exports to economies where consumers were willing to borrow to consume. In fact, consumption of Japanese exports increased in emerging markets too (also ultimately fueled by leveraging in the West). This came to a screeching halt in 2007. Since then, Japan has been self-funding its government by monetizing debt, promoting a global Yen carry trade, and levering domestic public and private balance sheets further. Japan’s Debt-to-GDP and Debt-to-Base Money ratios are now in a class by themselves among advanced economies.So what is happening now that leads us to think market recognition of these realities is approaching?

Late last year, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe began preparing the market for inflation targeting in 2013. General consensus was that the BOJ would begin aggressive QE until the Japanese annual inflation rate reached 2%. Sure enough the news hit the tape on January 21 – the BOJ would target a 2% rate by purchasing Japanese government notes and bills, but it would begin later than expected, in January 2014. The Yen, which had been weakening against the dollar, traded stronger on the day but its temporary strength had no chance of being sustained against the power of intervention hanging over the market.

The Yen trade shows two fundamentally critical points related to the global monetary system. The first is timing. Japan was the first major economy to blow itself up on unreserved credit and it was the first to suffer from it. Benchmark Japanese interest rates were dropped to literally 0% in 1999 and Japan was the first to begin QE in the 2001 – far in advance of the US and the Eurozone.

Japan’s economy was able to grow nominally from 2000 to 2007 through its exports to economies where consumers were willing to borrow to consume. In fact, consumption of Japanese exports increased in emerging markets too (also ultimately fueled by leveraging in the West). This came to a screeching halt in 2007. Since then, Japan has been self-funding its government by monetizing debt, promoting a global Yen carry trade, and levering domestic public and private balance sheets further. Japan’s Debt-to-GDP and Debt-to-Base Money ratios are now in a class by themselves among advanced economies.

Against this backdrop, the importance of outright inflation targeting by Prime Minister Abe cannot be understated for holders of all global currencies and precious metals. Japan’s policy treatment of the Yen continues to show the future for Dollar and Euro policy makers. In fact, there have already been unofficial discussions in the US and Europe about inflation targeting or its fraternal twin of sorts, nominal GDP targeting. As we have argued over the years, there is no other choice: goods and service price inflation must rise as currencies must be destroyed through dilution in order to reserve and reconcile existing bank credit/leverage. By threatening inflation targeting today, Japan’s economic triage placed the world on notice that it – and all other currency policy makers – are willing to stop at nothing to cheapen their currencies.

Masking this reality is the appearance of alternating strength in major currencies. Consider the strength of the Euro recently which surprised the great majority of FX traders, sure that it was going to find parity with the USD when it was trading around 1.20 (it is now around 1.35). The USD Index of major currencies (DXY) seems stable, but underneath this stability lies great strength in EURUSD and weakness in USDJPY (feet in the fire, head in the freezer => average temperature just right).

Masking this reality is the appearance of alternating strength in major currencies. Consider the strength of the Euro recently which surprised the great majority of FX traders, sure that it was going to find parity with the USD when it was trading around 1.20 (it is now around 1.35). The USD Index of major currencies (DXY) seems stable, but underneath this stability lies great strength in EURUSD and weakness in USDJPY (feet in the fire, head in the freezer => average temperature just right).

There may be periodically strong currencies but there are no currencies one should feel good about holding over time. As noted above, the state of play is rotating currency devaluations, coordinated by treasury ministries and central banks and executed by central banks.

As investors in precious metals plays, whether or not these managed FX machinations keep the different trade blocs nominally afloat is not our primary area of interest. We were actually most excited by Japan announcing it would delay inflation targeting by a year, our inference being Abe was counseled by US and Euro authorities that by merely announcing the plan (as was done on January 21) Japan would ensure a weaker Yen in the interim, but that more time was needed to coordinate a final, more comprehensive global currency solution.

We expect discussion of Fed, ECB and BOE inflation and/or nominal GDP targeting to become louder and more frequent in 2013, and we expect markets to begin adjusting asset prices accordingly.

As far as reading political tea leaves, it is the second term of a US presidency, a bank-friendly US Treasury Secretary was replaced, and the economic conversation among US politicians is ideological – whether or not to raise debt ceilings. Global economic power resides almost solely in the hands of central bankers. Ben Bernanke has a year remaining on his term, Fed-compliant John Carney takes the seat at the BOE, and pragmatist Mario Draghi has established credibility among European banks and is ready to print. To own precious metals and precious metals miners is to bet with central banks.

The Pain Trade

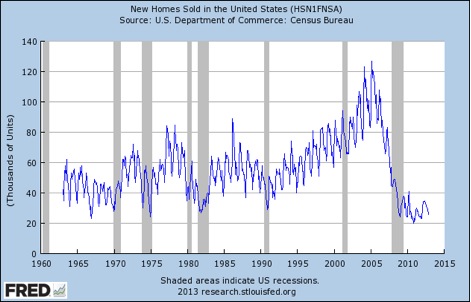

It has been absolute misery to look at the screens every day, having built a short position in homebuilders as their shares have risen over the past four months. Our rationale has been based on a few major reasons. Beyond all our views on nominal economic growth (possible) vs. real economic growth (virtually impossible), and the waning bid for more leverage among home speculators, and aging demographics implying more and more potential homebuyers will be downsizing, and the diminished ability of mortgage lenders and brokers to fund and service mortgages, and the significant percentage of homes currently worth less than their mortgages (which reduces current home sale liquidity), and mortgage rates that imply no future advantage for potential home purchasers (which reduces future home sale liquidity), and the recent uptick in home sales derived from block purchases by a few private equity buyers in targeted markets at distressed levels[1] — beyond all that – there is the graph below:

Simply, all the Sturm and Drang in the financial press about a revival of the US housing market is bologna. While Asians, Russian and Greek multimillionaires may be actively buying $20 million homes, there has been no fundamental rebound in the US housing market, perhaps for some or all of the reasons we cite above. The inventory and shadow inventory of existing homes for sale far outweighs the market for them. Since there is no improvement in the market for existing homes, we do not understand how investors could get excited by owning shares in companies determined to build more of them.

And there is one more thing about homebuilding stocks worthy of mention. The dynamic that would drive the housing market higher would be the general sense that tomorrow homes and everything else will cost more than they do today (i.e., inflation). Inflation would apply not only to homes but to materials needed to build them. We think that when goods and service inflation begins to take hold, the costs of lumber, copper, drywall, labor, etc. are sure to rise at least as much as the rate of new home prices and sales. So, while inflation might eventually “fix” the housing market, we think homebuilders will be left behind. Their product should be uncompetitive for a generation.

Against this backdrop, a graph of recent homebuilder share performance, as expressed in a homebuilder ETF, shows they have appreciated almost three times since the summer 0f 2011. (Go ahead, squeeze us more, but you better cover before it turns.)

Bad Science

On February 1, the Head of Precious Metals Research and the Head of Strategy for Commodities, Foreign Exchange and (curiously) Asia at a SIFI bank published a report that called the end of the bull market in gold, claiming; “the 2011 high will prove to have been the peak for the USD gold price in this cycle, and that (the) “the beginning of the end” of the current golden era comes sooner than the Q3 we forecast in January.”[1]We believe the timing of the report makes sense, given its provenance, and that it may be followed by more such reports from SIFI banks, especially those likely to be short physical bullion vs. outstanding claims for it they may be obligated to fill.

While no one definitively knows the future and the dollar price of gold may rise or fall (you know our view and rationale), we are quite certain gold’s future path will have nothing to do with the arguments included in this report. Sadly, it was a case study in false identities leading to wayward causations and, in our view, a diametrically wrong conclusion. Below, we briefly annotate two broad examples:

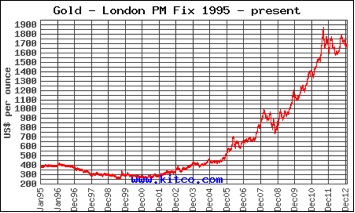

Claim: The Lehman event in 2008 began an “inflationary fix” that led to a “flight to quality” among investors that included Treasuries and gold.

Reality: The year-end trough in USDXAU (the dollar price of gold) came in 2000, eight years before the Lehman event. From year-end 2000 to 2007, spot gold increased over 200%, from about $272 to about $836 per ounce. Further, in 2008 – the year of the Lehman collapse – gold rose only about 4% to about $870/oz. Since then, gold rose another 90% to $1,664/oz. through year-end 2012. In fact, gold has risen each year for 12 successive years, from 2001 to 2012.

By any reasonable measure it does not seem that the price of gold subsequent to the Lehman collapse had anything to do with the event per se. In fact, a strong case may be made that since 2000 gold had been pricing in the fundamentals that led to the Lehman collapse, that being the record build-up of unreserved leverage in the banking system and the future need to de-lever it.

Finally, conflating gold and Treasuries in an investor “flight to quality” displays a very incomplete understanding of the fundamental forces behind each, and the incentives of the marketplace and official entities to sponsor them. The global financial system has been using Treasuries as a surrogate for gold reserves for over four decades. Is this surprising? No. Is it sustainable? Doubtful. Treasuries are in the process of demonstrating they are available in near infinite supply while gold’s physical stock struggles to grow more than one-percent per annum. Gold is thus a threat to the perpetuation of this peculiar, self-referencing system – not an ally. Gold and Treasuries are like oil and water in this regard. Holding gold is a hedge to holding Treasuries. If one is a safe-haven, the other is a time-bomb. History bears this out. In fact, when thought through logically and cohesively, being long gold is being short Treasuries, in real terms.

Claim: “Given its historical role as a store of value, it was not surprising that investor demand for gold increased substantially. Now, however, with the acute phase of the crisis likely to be behind us, we think the peak of the fear trade has now also passed.” The analysts continue; “against any sensible benchmark gold still appears significantly overvalued relative to the long run historical experience.”

Reality: Whether it has been government-sanctioned money or not, gold’s role has empirically been the same as money’s – to store purchasing power. Sometimes, societies may collectively believe, correctly, that there is more purchasing power to be gained by converting their money into levered financial assets over some period of time. However, when levered financial assets are further denominated in unreserved currencies, then it would seem highly likely that at some point scarcer gold would protect its holders’ purchasing power better than money or financial assets. Gold’s quantity is relatively static while money’s quantity must be greatly inflated tomorrow in response to credit inflation today.

Such is the store of value to which the analysts refer. By implication, they are asserting that the future rate of money growth will be less than the future rate of the gold stock. With global central bank Quantitative Easing in full flare, this assertion is quite confusing. We would agree that the shock of recognition of bank system leverage has passed, but we would not agree that “the acute phase of the crisis likely is behind us” or that “the peak of the fear trade has now also passed.” We do not believe the analysts understand the driver of gold prices in the US or around the world. The fundamental reason USDXAU has risen since 2000 has been the anticipation and ongoing confirmation of global base money stock inflation.

As we have discussed, we believe the central bank mission to de-lever banks through reserve creation is in place so bank balance sheets will be strong enough to endure necessary economy-wide price inflation, which in turn would de-lever government and household balance sheets. We think the Fed and other central banks expect the following economic sequencing: banks de-lever further via bank reserve creation => goods and service price inflation rises naturally as global producers demand more monetary units (higher prices) for their production => economic activity slows, creating a stagflationary global environment => by then well-reserved banks will buy or lend to borrowers willing to purchase distressed assets => asset prices rise and banking systems and economies begin to re-lever => wage levels rise relative to household debt levels, reducing the burden of grass roots debt repayment. (The wheel in the sky keeps on turning.)

In other words, we believe central banks in advanced economies are united in pursuing inflation as a remedy for economic leverage. (We further believe they will succeed, but will be forced by the market to greatly condense the sequence above into policy-administered currency devaluation.) If our analysis is correct, then “the peak of the fear trade” is ahead of us, not behind us, and the magnitude of the fear trade is substantially larger than implied by past USDXAU gains.

The True Lesson of JMK

John Maynard Keynes was truly deserving of his stature as one of the greatest economic thinkers of the twentieth century. He got it, as they say; consistently demonstrating what seems to be complete knowledge of the organic forces of economics and the power of government forces to twist them to its aims. What might JMK say today about saving one’s wages in the currency in which it was earned or investing them in today’s financial asset markets? Perhaps this:

“Lenin is said to have declared that the best way to destroy the capitalist system was to debauch the currency. By a continuing process of inflation, governments can confiscate, secretly and unobserved, an important part of the wealth of their citizens. By this method they not only confiscate, but they confiscate arbitrarily; and, while the process impoverishes many, it actually enriches some. The sight of this arbitrary rearrangement of riches strikes not only at security, but at confidence in the equity of the existing distribution of wealth. Those to whom the system brings windfalls, beyond their deserts and even beyond their expectations or desires, become ‘profiteers,’ who are the object of the hatred of the bourgeoisie, whom the inflationism has impoverished, not less than of the proletariat. As the inflation proceeds and the real value of the currency fluctuates wildly from month to month, all permanent relations between debtors and creditors, which form the ultimate foundation of capitalism, become so utterly disordered as to be almost meaningless; and the process of wealth-getting degenerates into a gamble and a lottery.

Lenin was certainly right. There is no subtler, no surer means of overturning the existing basis of society than to debauch the currency. The process engages all the hidden forces of economic law on the side of destruction, and does it in a manner which not one man in a million is able to diagnose.”

JMK was of such a mind in 1919 amid the turbulence following the Great War, concurrent with reparation debates, and just prior to the Great Weimar inflation. And now consider this insight mere months after the October 1929 stock market crash amidst the onset of the Great Depression:

“When the accumulation of wealth is no longer of high social importance, there will be great changes in the code of morals. We shall be able to rid ourselves of many of the pseudo-moral principles which have hag-ridden us for two hundred years, by which we have exalted some of the most distasteful of human qualities into the position of the highest virtues. We shall be able to afford to dare to assess the money-motive at its true value. The love of money as a possession — as distinguished from the love of money as a means to the enjoyments and realities of life — will be recognised for what it is, a somewhat disgusting morbidity, one of those semi-criminal, semi-pathological propensities which one hands over with a shudder to the specialists in mental disease … But beware! The time for all this is not yet. For at least another hundred years we must pretend to ourselves and to everyone that fair is foul and foul is fair; for foul is useful and fair is not. Avarice and usury and precaution must be our gods for a little longer still. For only they can lead us out of the tunnel of economic necessity into daylight.”Keynes’ diametrically diverging opinions in the space of ten or so years is reminiscent of Alan Greenspan’s, who in 1966 authored a Libertarian screed that to this day is one of the most eloquent cases for maintaining the gold standard.[1] Of course, as Fed Chairman, he seemed to stretch unreserved fiat credit money to its limit (before Chairman Bernanke went even further).

Modern economists may think of such transformations as growth – from principled positions based on natural economic function to more practical macroeconomic problem solving. In fact, as we have noted in the past, this practical political economic mindset dominates current thinking and policy.

But here is where modern political economic theory will fail (listen up Misters Goolsbee and Krugman). The issue is not one of principle; it is one of perceived fairness. Politics will follow perceived fairness and so political economics will be dragged with it too – just as Misters Keynes and Greenspan were. Indeed, Lord Keynes knew and was happy to elucidate the great difference separating what was useful and what was fair (“we must pretend to ourselves and to everyone that fair is foul and foul is fair; for foul is useful and fair is not”). He knew in 1930 that fairness and the perception of it were two very different things.

Our purpose here is not to directly debate morality or fairness but to focus on the near-term sustainability of “avarice and usury” as Keynes said – let’s call it the focus on money, per se – as central to economic functioning. Should Keynes’ “at least another hundred years” projection in 1930 be seen as a scientific reality, implying there is no need to begin worrying until 2030? Or, should we heed his advice in general terms, knowing he was partial to dramatic pronouncements, and consider his prediction in light of the inevitability it implies in relation to current events?

The point is this: periodically there is a need to change the system, if only for change’s sake, because there comes a need for the masses to believe – truly believe – that change equals more fairness. The answer is not in which direction it changes, only that indeed it changes.

In Macro Polo last month we sought to make a general case for the inevitability of monetary system devaluation. Were he alive and active today we believe Lord Keynes would also argue for the same inevitable solution he knew was necessary in the 1930s – administered currency devaluation. Why? Not only is devaluation necessary and already underway in the marketplace, thereby giving it a sense of inevitability, but its proclamation would legitimize its public claim on fairness.

We think JMK would say it is time to devalue and reconcile accounts and he would use the same arguments today that he used in 1930 for government intervention.

Policy Administered Gold Monetization

Currency devaluation may be achieved through rotating currency interventions by treasury ministries and central banks or through a one-time coordinated asset monetization. (Current debt monetization in the form of QE is NOT asset buying. To the contrary, it is central bank credit extension.) When it comes to asset monetization, gold – rather than corporate shares, real estate or consumable commodities – is clearly the most established, convenient and socially acceptable medium for fiscal agents and monetary authorities to endorse. Why? First, gold is equity already held on official balance sheets – treasury ministries and/or central banks. Second, the purchase of gold through a currency devaluation process would not necessarily be an unfair confiscation of popular wealth, which is critical in democracies where governments and their agents are not supposed to take ownership of private property.

Through policy-administered currency devaluation, fiscal agents and monetary authorities would bid for gold in terms of their currencies. Imagine the following pronouncement, if you will:

“Today, the Federal Reserve System announces a program of gold monetization in which the Fed offers to tender for any and all gold in qualifying forms at a price of US $20,000 per troy ounce. The program will be conducted through participating U.S. chartered banks, which will be instructed to properly assay gold and exchange it for U.S. dollars to be placed in customer bank accounts as deposits. Deposit holders will be entitled to make withdrawals in the form of dollars or gold at the fixed exchange rate.

By establishing the fixed exchange rate substantially above past market prices for spot gold, the Board of Governors believes enough gold will be tendered to produce a supply of new base money sufficient to adequately reserve the stock of U.S. dollar-denominated deposits in the global banking system. The Fed will monitor the tender process to ensure the soundness of the exchange rate and the ongoing viability of the US dollar.”

Done. The trillions in net unreserved bank obligations, including those appearing and not appearing on bank balance sheets, would be fully reserved. Banks would be healthier than ever and ready to lend. The debt on the balance sheets of businesses, homeowners, consumers, college graduates and car owners would still be there but would pale next to their new incomes, which would multiply more or less by the same amount as the currency devaluation. Tax receipts would multiply in kind – without raising marginal income tax rates – swiftly closing budget deficits without cutting spending (seriously). With coordinated and administered monetary devaluation all balance sheets would once again be leverage-able. The global economy would be almost immediately ready to grow. It would be economically stimulative.

We think administered currency devaluation must and will occur, as it is already occurring less formally. Banks and central banks would endorse it; their profitability would soar as lending soars and interest rates would remain low and stable. Politicians would happily champion it, as it would seem to the majority of the indebted and increasingly under-employed electorate to be a windfall solution.

Okay Smarty-Pants, When?

…7…6…5…

The Play

We think there are two almost riskless investment schemes to consider presently for levered portfolio managers that cocktail with central bankers and fiscal agents:

1) Mismatched duration carry trades (requires the knowledge that short term funding will never exceed the yield on portfolio longs)

2) FX cross rate positions (requires knowledge related to intervention timing and targets)

And there are two general investment areas to consider for the great unwashed investment class:

1) Long stocks/housing and other beneficiaries of leverage (only for those that think the global economy can lever more from current levels)

2) Long precious metals (if one does not think the global economy can lever more).

We think there is one play unlevered investors should avoid unambiguously:

1) Long cash and/or bonds as a secular holding.

Our overwhelming preference for precious metals and consumable inelastic resources stems from our view that the global economy is not yet in the process of de-levering (leverage is merely shifting), but that the markets will soon understand that it must de-lever soon through highly inflationary gold monetization. We believe such a portfolio is the least risky, best risk-adjusted portfolio construction in the current environment because:

• the general performance of financial asset markets has become contingent upon maintaining low nominal (and negative real) global interest rates

• interest rates can be maintained at current levels only by growing central bank balance sheets

• the pricing of precious metals, precious metal miners, and consumable resource producers are significantly more undervalued within this context.

We think the table is set for certain precious metal mining stocks to begin outperforming most all other instruments in 2013. Not only have they been thoroughly discarded by investors over the last two years in spite of what we believe is a building perfect storm to send them much higher, but; 1) they have streamlined their resource targets and fortified their balance sheets; 2) marginal US capital gains tax rates were set in January at lower-than-collectible tax rates (including bullion and ETFs); and 3) it seems the world’s most sophisticated investors have already begun taking a decent slug of their market caps.

The fundamentals of their underlying product could not be better. Central banks cannot stop growing their balance sheets via debt monetization because higher nominal rates would force governments into bankruptcy and would kill the banking system before it is better reserved. The cost of this ongoing bailout is the slow death of un-levered savers and fixed income investors in real terms.

Through negative real rates, bond holders are effectively being cordially invited to sell their bonds to central banks, and to place the proceeds into equity in the form of corporate shares and real estate. Meanwhile, savers are being given the clear message to convert their cash from Dollars, Euros, Yen, etc. to precious metals. We think that what will eventually (or soon) occur will be the rare occasion when return-on-savings trounces return-on-investment, implying precious metals will outperform the great majority of financial assets (except for shares in precious metals miners and natural resource producers .

As the song goes: “you gotta know when to hold ‘em; know when to fold ‘em; know when to walk away and know when to run.” Most investors, by definition, will hold ‘em. Wealth has already flowed from the great majority holding unreserved paper claims to those that helped them leverage their balance sheets in return for fees. Bonds at current valuations are certainly not safe-havens, nor are the great majority of stocks “the new gold.” Looking forward, we think windfall profits – real profits adjusted for necessary currency devaluation – will flow to savers of scarce treasure and ownership shares in it.

Source:

Lee Quaintance & Paul Brodsky

Locked & Loaded

QBAMCO, February 2013

pbrodsky.qbamco.com

What's been said:

Discussions found on the web: