Election ‘Uncertainty’ Isn’t Messing With Markets

The outcome of the presidential race is merely unknown. That’s something entirely different.

Bloomberg, May 20, 2016

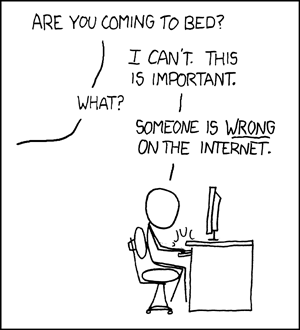

Every now and again, something is filled with so much wrong that it cries out for a response. Much of the time, we are obliged to let such errata pass unnoted, lest fisking what is wrong becomes a ’round-the-clock job. As the old saw goes, choosing your battles wisely is the way to exhibit wisdom and win the war.

Still, now and again, something demands a response — in this case it’s the reappearance of an old meme that refuse to die: “Uncertainty” as an explanation for some pattern of behavior, especially the reluctance of investors and businesses to make plans for the future.

Still, now and again, something demands a response — in this case it’s the reappearance of an old meme that refuse to die: “Uncertainty” as an explanation for some pattern of behavior, especially the reluctance of investors and businesses to make plans for the future.

The latest spasm of uncertainty concerns the presidential election, and the idea that an abundance of said uncertainty in years when there is no incumbent running holds back financial markets and the economy.

Let’s examine some of the evidence cited in support of this idea: Since 1928, in election years with no second-term incumbent running, the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index has fallen an average of 2.8 percent.

We can assume that this fact is true. But so what? (I don’t even understand why 1928 was picked since you have to go to 1952 to find an open election, with Eisenhower versus Stevenson.) Here’s the real problem, though. With just six elections without an incumbent since World War II, the sample size is way too small to draw any meaningful conclusions. Even if we consider the entire 20th century (there were five open elections before 1928) that’s a data set of just 11 — still a rather small sample set to use in any sort of analysis.

And if we look at the last year of an incumbent’s eight-year term — the only year that averaged negative returns — it’s an even smaller group (1904, 1920, 1960, 1988, 2000 and 2008).

These results are indistinguishable from randomness. I asked Salil Mehta, author of “Statistics Topics,” and former director of analytics for the Troubled Asset Relief Program, about this. His said that there can be a number of problems with drawing predictive conclusions from a small data set. There can be spurious anomalies, issues with causation and the presence of confidence intervals. “Seeing a short-term pattern but for the wrong reason,” he said, is often the result of small samples. Perhaps we can revisit this in a few centuries when we have a more meaningful data set.

But the bigger issue is uncertainty meme itself, which gets trotted out on a regular basis. We have addressed this before (see this, this, this, and this), but we are perhaps due for a revisit.

Uncertainty is a condition that exists when the set of possible future outcomes is unknowable. Note that this is very different from an event which is merely unknown.

A flip of a coin isn’t uncertain — it’s either going to be heads or tails (you can even foresee the one in a billion landing on its edge). For a pair of dice, it’s all of the integers between two and 12. The outcome may not be known before the roll or the toss, but the range of possible outcomes is known and statistically well understood.

When we have no idea what the possible range of outcomes are, that is when we can describe something as uncertain. War is often a good example of this; consider the uncertain prospect of the invasion of Iraq in 2003 leading to the rise of Islamic State in 2014.

We often hear the phrase “uncertainty” used when people are uncomfortable admitting a lack of ability to foresee the future; anecdotally, this seems to be especially true when they have been recently wrong.

Which brings us to the presidential race and the uncertainty trope.

Just about all of the pundits were wrong about the Republican primary race; similarly, the Democratic race was supposed to be over long ago. The establishment of one party and the more enthusiastic activist base of the other are unhappy with the presumptive nominees. That combination of “wrongness” and dissatisfaction has once again led to the misuse of that word again.

The outcome of the U.S. 2016 presidential race is anything but uncertain: It’s either going to be either Donald Trump or Hillary Clinton (that one in a million chance of Bernie Sanders is rapidly fading). The two frontrunners have been on the stump for a long time. Both are very well-known quantities. To say that the outcome is uncertain is to misunderstand what that word means.

You may not love the choice of candidates. You may not be happy with their policy positions. Maybe you’re even toying with leaving the country if one or the other of the candidates wins. But this much is certain: it’s only the outcome of the election that is unknown today. But that is something very different from “uncertain.”

Almost every time I see “uncertainty” in print, I am reminded of the movie “The Princess Bride,” when Inigo Montoya says “You keep using that word. I do not think it means what you think it means.”

Keep that in mind the next time someone tells you that uncertainty accounts for something unpleasant in markets or the economy.

Originally: Election ‘Uncertainty’ Isn’t Messing With Markets

What's been said:

Discussions found on the web: