The Survival Rate of the Smallest Establishments During the Great Recession

by James D. Eubanks and David Wiczer

Economic Synopses, St Louis Fed, 2017-05-12

Very small establishments closed at about twice the rate of larger ones.

The Great Recession, in addition to its other large economic effects, significantly cut the number of companies operating in the United States. According to Census statistics, the number declined an aggregate 5 percent from 2007 to 2010.1 This is an important and well-documented feature of business cycles—as production growth declines, so does growth in the number of companies. In this essay, we examine this phenomenon by focusing on the smallest production units in the economy: very small establishments, a term used here to mean establishments with no more than five employees.2 In the Great Recession, very small establishments exited at a rate nearly twice as high as the economy average. They also saw a much larger decline in sales if they did survive. But even very small establishments with relatively more sales did not have a lower exit rate.

The National Establishment Time Series (NETS), the data we use to reach these conclusions, is somewhat unique. The NETS uses business information from the credit rating firm Dun and Bradstreet, which tries to cover comprehensively all establishments in the United States. The resulting sample is not necessarily universal or representative, but it includes many more very small establishments than widely used Census data, which often miss very young establishments or those in which the owner is the only employee. The NETS, however, under-represents larger establishments. In the 2007-10 period we study, there is an average of 7.5 workers per establishment.

The NETS is particularly useful because it contains crucial information for understanding firm dynamics. The data are annual, following the same firms and recording their status every January. Dun and Bradstreet is very careful to accurately measure closures; otherwise, a firm falsely reported closed would artificially get a blank credit history. The NETS also contains data on the self-reported number of workers and sales. These data are known to be imprecise. For example, the total number of employees in the dataset is about 16 percent larger than the total U.S. labor force. For our purposes, however, they are a near-enough approximation because we will use employment only to coarsely define size categories.

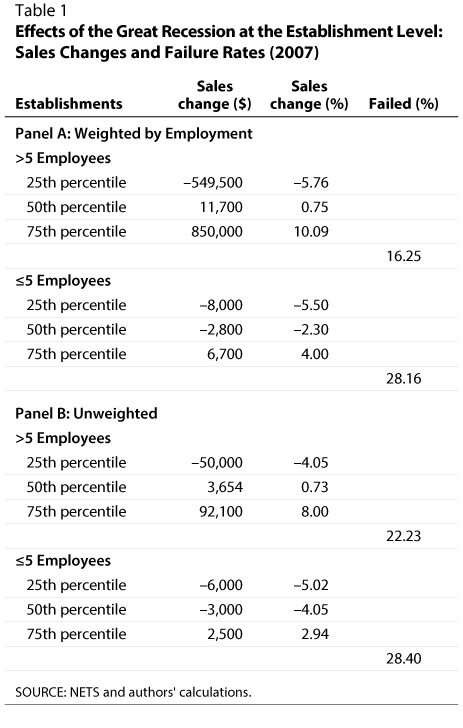

We take the cross-section of establishments operational in January 2007 and split them between those with more than five employees and those with five or fewer. The NETS counts everyone working at an establishment as an employee, including the owner, so no operational establishment will have fewer than one employee. Table 1 shows, conditional on survival, the average change in total sales of each group in 2007 by quartile and the percentage of each establishment group that had closed by 2010, after the end of the Great Recession. For each of these statistics, we count each establishment equally or weight by employment.

As Panel A of Table 1 shows, very small establishments closed at twice the rate of larger ones. Among workers at very small establishments, more than one in four were displaced because their shop did not survive the Great Recession, while that number was about one in six for workers at larger establishments. Looking at sales, very small establishments also were more badly hit. At the median, sales were approximately unchanged for larger establishments but fell considerably for very small ones. The bottom quartile of very small establishments lost the most overall, and the top quartile gained far less compared with the same quartile for larger establishments.

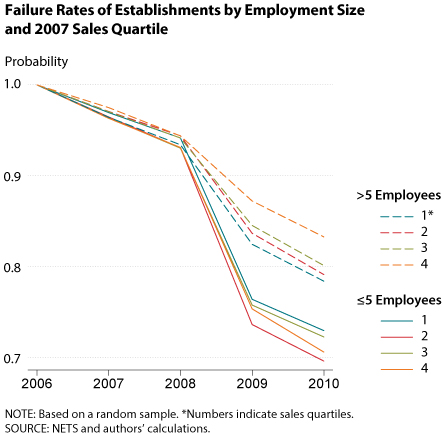

To better understand the failure rate of very small establishments, Table 2 shows the average total sales of establishments by employment size and quartile. Then, in the figure, we plot by quartile the fraction of establishments—weighted by employment—that survived from one year to the next. The breakdown shows that conditions in 2008 particularly disproportionately affected very small establishments. While their average survival rate was within 2 percent of the larger establishments’ rate before 2008, it increased dramatically to more than 10 percent after 2008.

Notice in the figure that among the larger establishments, those with the most sales closed less frequently. Among the very small establishments, however, sales scarcely mattered to their survival rate. The least likely to survive are actually in the second sales quartile, while the most likely to survive are the smallest establishments. This finding is surprising if we believe larger operations are more resilient to shocks.

In the NETS, economists have a unique window into many very small establishments. Studying them in particular is important because they often do not follow the same trends as their larger peers. Here, we have shown that in some ways they are much more cyclically sensitive. However, within the group of very small establishments, the smallest are not the most vulnerable.

~~~~

Notes

1 See Seimer, Michael. “Firm Entry and Employment Dynamics in the Great Recession.” Finance and Discussion Series No. 2014-56, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, July 2014; https://ideas.repec.org/p/fip/fedgfe/2014-56.html.

2 An “establishment” is a single physical location where goods or services are produced. This is different from a “firm” or “company,” synonyms for a business entity that owns physical or intellectual property and may operate several establishments.