Everything must go

A rash of store closings is a sign that the ground has shifted under bricks-and-mortar merchants, with consequences for the retail sector and district communities

PHIL DAVIES

Fedgazette, September 19, 2017

A liquidation sale follows, and over the next few weeks, shoppers and resellers hunting for bargains strip the store down to its fixtures. Finally, the doors are locked, the lights turned out and a place that was once a hive of commercial and social activity is left a hollow shell fronted by an empty parking lot.

This sequence has played out numerous times this year in the Ninth District, in big cities such as Minneapolis (where Macy’s closed its downtown store, ending 114 years of retailing in that location) to small cities such as Jamestown, N.D., and Thief River Falls, Minn., which lost their J.C. Penney stores.

The list of other well-known retail brands that have shuttered stores in the district and across the country includes department stores Sears, Kmart and Gordmans, and specialty retailers Gander Mountain, The Limited and Payless Shoesource. Some of these firms have declared bankruptcy and are winding down their operations.

Vacant storefronts have always been part of the retail landscape. Defunct stores make way for new market entrants in a continuous process of creative destruction that fosters economic growth. But the large number of store closings in the district and throughout the United States so far this year is notable—an indication that many large retailers are struggling to keep their doors open in a hypercompetitive industry in the throes of change.

“There’s a shift under way, led by consumer preference,” said Steve Goldberg, president of The Grayson Co., a New York City-based retail consulting firm. “People like to shop in stores, but the economics are starting to fray.”

Increased store closings in recent years have been widely attributed to the “Amazon effect”—the popularity of shopping on the internet instead of in physical stores. But it’s likely that the spate of closings is also being driven by demographic change, evolving consumer tastes and, in some parts of the district, a downturn in agriculture and oil drilling.

Store closings may have a minimal impact on consumers; most households have multiple shopping options, including purchasing online. But for communities, the effects of store closure—especially that of a large store such as a mall anchor—can be significant. When a store closes, residents lose their jobs, and prolonged store vacancies can weaken shopping centers and undermine property values.

Store clearance

Retail store chains typically announce closings after the year-end holiday shopping season; stores that performed poorly are targeted for elimination. But closures have become more prevalent over the past two or three years, and in 2017 the triage process was particularly brutal, with wave after wave of closing announcements. Investment bank Credit Suisse estimated in April that as many as 8,600 U.S. stores could close by year’s end—far more than the record 6,200 stores that closed in 2008, the first year of the Great Recession.

In January, Sears Holdings said that it would close 109 Kmart stores and 41 of its namesake Sears outlets nationwide, the latest surge of closures by the troubled retailer. The Sears store in South Fargo, N.D., and the Kmart in Sioux Falls, S.D., were on the list of soon-to-be-closed stores. Three more rounds of closures have followed, bringing to 250 the number of unprofitable Sears and Kmart stores that have closed so far this year.

Macy’s announced the closure of 68 stores nationwide, including the iconic former Dayton’s in downtown Minneapolis and the Macy’s in the Columbia Mall in Grand Forks, N.D. In a press release, Macy’s described these closings and others announced last fall (such as the shuttering of a store in Eau Claire, Wis.) as a “series of actions to streamline its store portfolio, intensify cost efficiency efforts and execute its real estate strategy.”

Through the spring and summer, other major retailers followed suit, announcing their own downsizing strategies: J.C. Penney (over 130 stores closed, including outlets in small communities such as Thief River Falls, Yankton, S.D., and Sidney, Mont.); Gordmans (at least half of the chain’s 100-plus outlets to close under new owner Stage Stores of Texas); St. Paul-based outdoor retailer Gander Mountain (one-third of 160 stores to close after a buyout by retail mogul and TV personality Marcus Lemonis).

Nationally, retail bankruptcies rose to their highest level since the recession in 2016, and industry analysts expect 2017 to be another big year for defaults and company liquidations. Retailers that have declared bankruptcy and gone out of business include a number of firms with operations in the district. Vanity, a women’s fashion retailer based in Fargo, N.D., said in March that it would close all 137 of its stores and lay off 1,200 workers. Clothier American Apparel, electronics and appliance retailer HHGregg and footwear discounter Payless ShoeSource also defaulted on their debts and closed all their outlets.

The retail bloodletting seems out of step with the overall state of the U.S. economy, which has continued to improve over the past couple of years, with rising employment and wages. “Notwithstanding a good economy, these companies are all having problems,” said Robert Schultz, managing director of S&P Global Ratings, a credit rating and risk analysis firm.

And the broad scope of the store closings—stores have gone dark at an increased pace in every district state, and in metro areas as well as in rural communities—indicates that something is amiss in an industry long accustomed to swelling revenues and the inexorable spread of storefronts.

Ripe for consolidation

By some measures, the retail sector appears in robust health; adjusted for inflation, U.S. retail sales and employment have rebounded from the recession and stayed on an upward trajectory, according to government statistics (Chart 1). But there are signs that the industry has run into headwinds, both nationwide and in some district states.

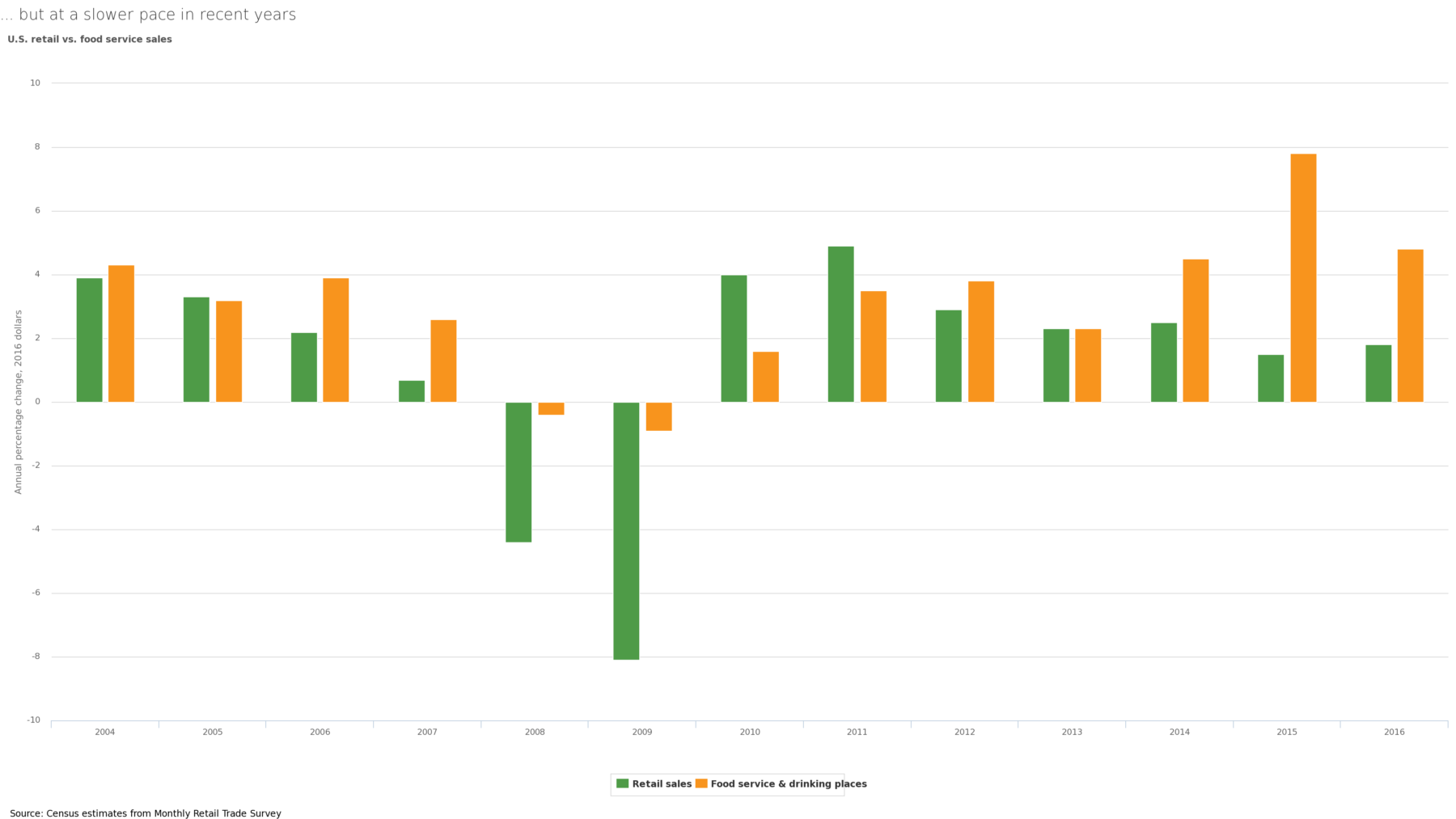

From 2011 to 2016, growth in national retail sales slowed in real terms (Chart 2). During the same period, sales by food services and drinking places, an industry category that is sometimes included in the retail sector, grew at a much faster annual rate. (However, in the first quarter of this year, retail sales increased 1.8 percent year over year, more than food service sales.)

Source: Census estimates from Monthly Retail Trade Survey

… but at a slower pace in recent years

In the district, some states have seen either slow growth or declines in taxable retail sales and employment in recent years.

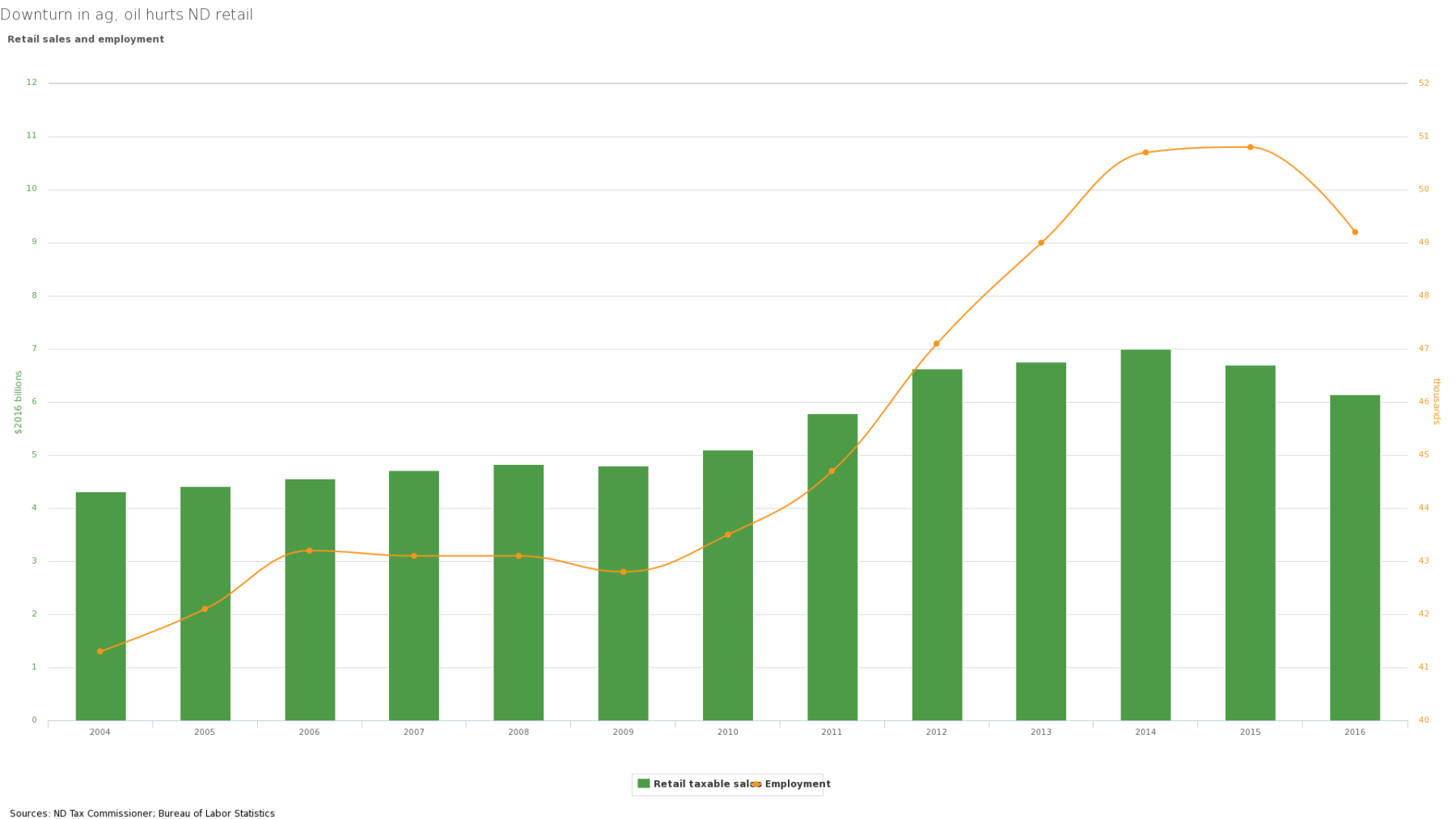

In North Dakota, taxable retail sales reported to the state have flattened and declined since 2012, ending several years of steady increases interrupted only briefly by the recession (Chart 3). Retail employment fell in 2016, and the drop-off in store jobs continued this year, with monthly year-over-year declines through June.

Retail trade in South Dakota has followed a similar pattern, according to the state Department of Revenue; taxable sales in miscellaneous retail, a broad category that makes up about 20 percent of retail sales in the state, fell about 8 percent in 2016, the third consecutive year of annual declines.

A drop in agricultural commodity prices since 2014 is largely responsible for retail setbacks in the Dakotas. Agricultural producers have reined in their spending (see Trouble on the Farm), shrinking sales of not only agricultural suppliers but also Main Street businesses such as hardware stores, appliance outlets and apparel shops. “Other industries and businesses are dependent upon the farmer coming in their door, and if that farmer doesn’t have the dollar to spend, they don’t have the dollar to spend either,” said Douglas Schinkel, director of the South Dakota Department of Revenue.

In North Dakota, merchants have absorbed the impact of not just lower ag spending but also a slowdown in the Bakken oil fields due to low oil prices.

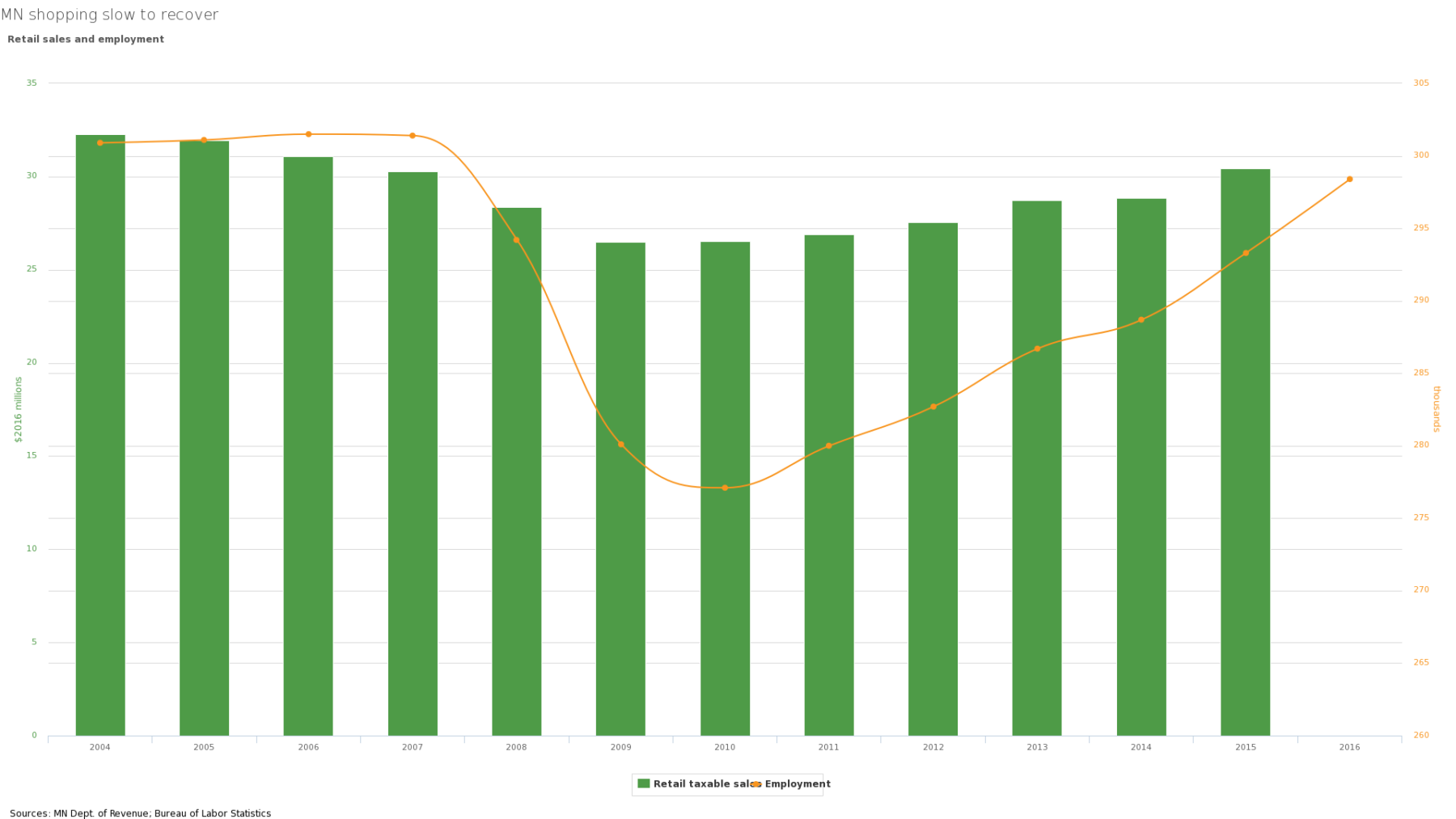

Minnesota’s diverse economy has insulated retailers in the state to some degree from the downturn in the farm economy (Chart 4). The state hasn’t seen sharp declines in taxable retail sales in recent years, and sales increased 6 percent in 2015, the latest year for which data were available from the Minnesota Department of Revenue. But statewide sales have yet to rise to levels attained in the years leading up to the recession. Nor has retail employment fully rebounded from the downturn; peak employment in this labor-intensive industry was in 2006.

Retail appears to have fared somewhat better in other district states. Wisconsin sales and use tax collections have increased steadily since the recession and last year exceeded inflation-adjusted 2007 levels. In Montana, retail employment rose to its highest level ever last year, although employment fell year over year in the first half of this year.

Slower growing or falling retail sales across much of the country, including parts of the district, make the sector ripe for consolidation.

The U.S. retail market is richly endowed with bricks and mortar; the nation has about 40 percent more retail space per capita than Canada and more than double the per capita store space in Australia, according to the International Association of Shopping Centers. “We as a country, and Canada as well, are dramatically over-stored,” Goldberg said.

Much of this vast retail footprint was formed in the 1970s and 1980s, when the U.S. population and consumer spending were growing rapidly. Into the 2000s, retail chains continued to build stores in the belief that “your biggest opportunity to gain customers was to be in their neighborhood,” said Jerry O’Brien, executive director of the Kohl’s Center for Retailing at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Today, many merchandisers are closing stores to bring retail supply more in line with demand, said O’Brien, a former executive at Minneapolis-based Target Corp. However, closings in response to sales slowdowns or declines haven’t occurred evenly across the retail industry.

Retail experts attribute the recent slowing of sales growth nationwide—and the upsurge in shuttered stores over the past two or three years—to fundamental market changes that are hurting traditional department stores and other bricks-and-mortar merchants in certain retail categories. These changes—among them the disruptive effects of e-commerce—are likely to be longer lasting than the downturn in commodity prices that has depressed retail sales in some district states.

Not your mother’s shopping cart

The recession was a watershed event in terms of consumer behavior. Stagnant or incremental wage growth in the aftermath of the severe economic downturn led many consumers, especially millennials, to cut back on household spending and reorder their shopping priorities.

Those adaptations persist. A recent survey by Wolfe Research, a New York City-based market research firm, found that the buying habits of millennial women—those who came of age since 2000—differ from those of their baby boomer parents. Likely to rent instead of owning a home, they buy fewer household items and prefer to spend money on their health and experiences such as travel and recreation instead of material goods. The survey of over 1,000 young women nationwide also found that they are price-conscious, ever on the lookout for bargains.

Baby boomers are also shopping differently as they retire and downsize their households, Goldberg said. “As people age they buy less stuff; that’s a fact.”

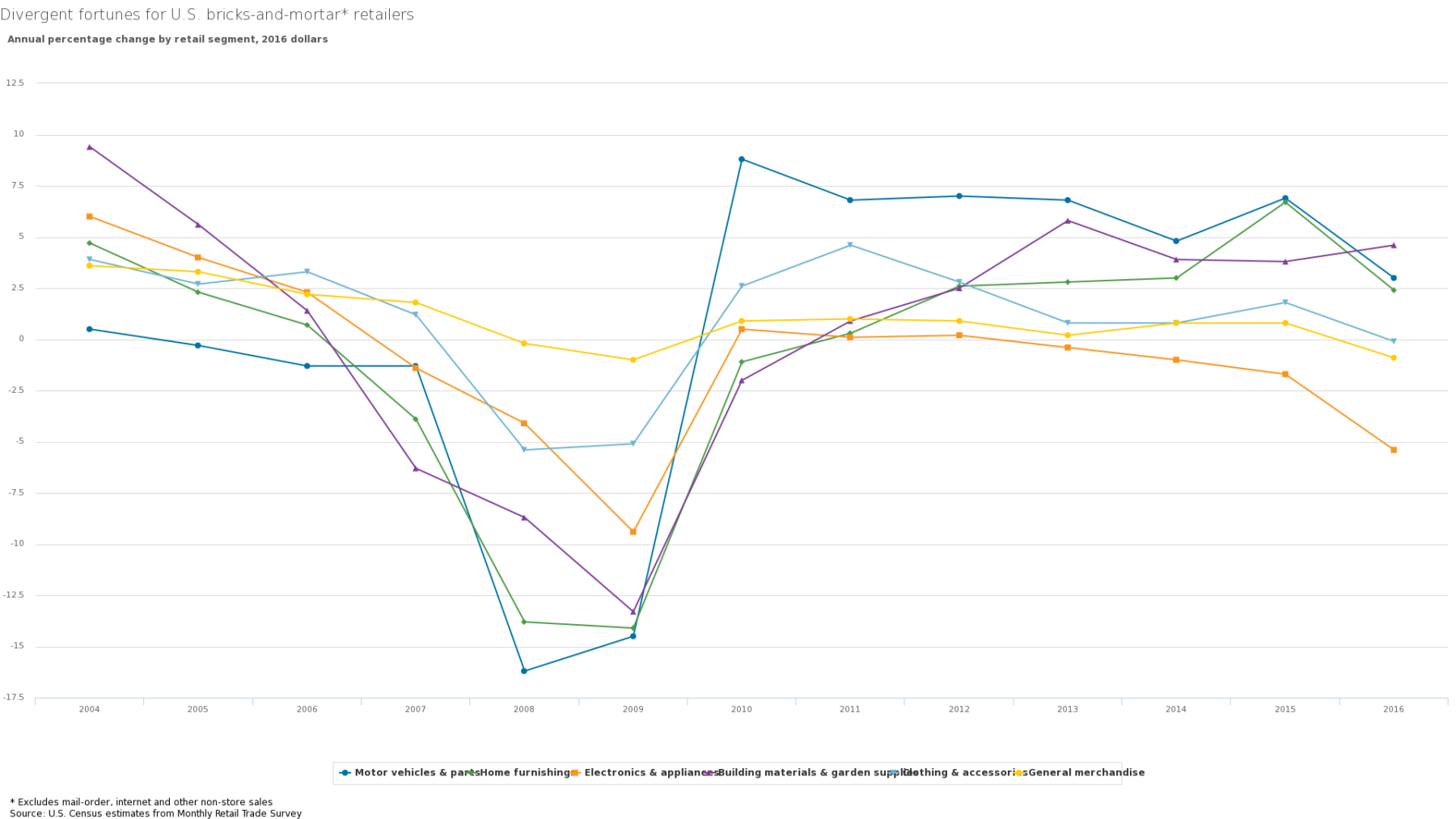

For bricks-and-mortar retail stores, sales growth over the past five years in general merchandise (including department stores), clothing and other categories has been either sluggish or negative (Chart 5). A substantial share of store closings nationwide has occurred in these troubled subsectors. Meanwhile, other lines of retail saw stronger growth, possibly reflecting revived housing construction and increased automotive sales since the recession.

* Excludes mail-order, internet and other non-store sales

Source: U.S. Census estimates from Monthly Retail Trade SurveyAnnual percentage change by retail segment, 2016 dollars

Divergent fortunes for U.S. bricks-and-mortar* retailers

A breakdown of store sales by category in Minnesota shows similar trends, with auto dealers and lumberyards faring better than department stores and electronics retailers.

Retail experts say off-price clothing retailers such as T.J.Maxx and Ross are also doing well, at the expense of department stores and full-price specialty retailers. “The one thing that has been consistent since the financial crisis is that consumers are focused on value and discounts,” Schultz said.

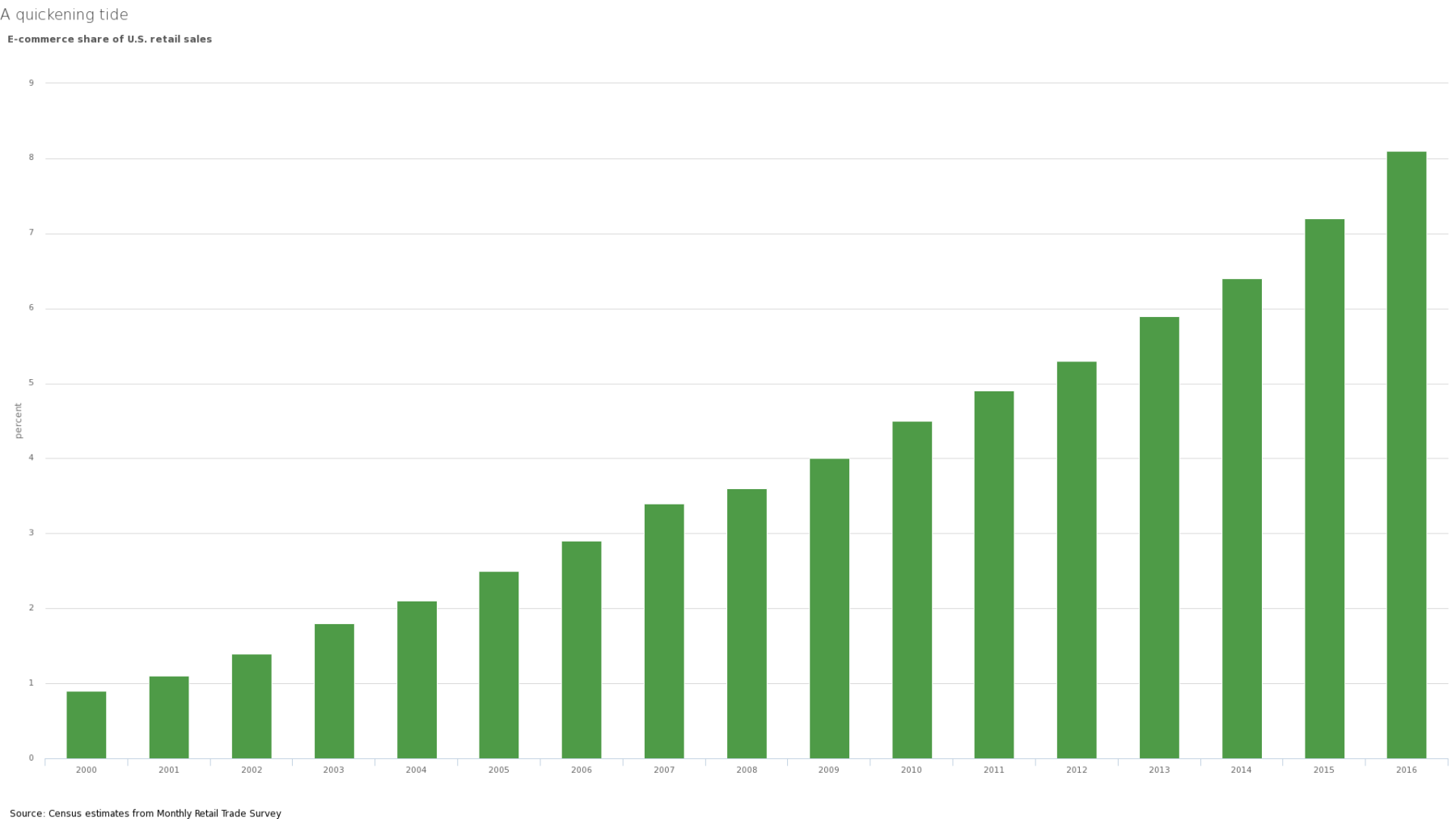

The Amazon effect is undoubtedly a factor in the varying performance of retailers and increased closings in beleaguered store categories. Although e-commerce accounts for less than 9 percent of U.S. retail sales, the market share of online merchants has increased dramatically over the past 15 years (Chart 6). As overall retail growth has slowed in recent years, accelerating online sales have cut deeply into the revenues and earnings of bricks-and-mortar retailers.

Source: Census estimates from Monthly Retail Trade Survey

A quickening tide

David Brennan, co-director of the Institute for Retailing Excellence at the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul, sees the 2016 holiday shopping season as “a tipping point, where the robustness of internet commerce has really come into its own.” The institute conducts an annual year-end survey that asks Twin Cities metro residents about their spending in various retail channels, such as regional malls, mail order, TV shopping channels and the internet. In 2002, web sellers netted about 7 percent of spending in the vital holiday period; in 2010, that figure was 22 percent, and last season it was almost 39 percent.

Notably, retail categories that are struggling are the same ones in which e-tailers have gained the most market share. Amazon is now the largest or second-largest apparel retailer in the country and the second-biggest electronics seller, behind Twin Cities-based Best Buy—which has itself aggressively ramped up online sales.

Millennials have embraced online shopping, rendered efficient and convenient by broadband internet access and ubiquitous smartphones. “This is something they’ve grown up with and are very comfortable with, much more so than the older folks, who are fading off into the sunset,” Brennan said.

Do store closings matter?

The majority of residents aren’t materially affected when a retail outlet closes in their town. They can drive farther to another store or shop at an online retailer, which may carry a wider variety of goods than was available at the closed store and offer lower prices to boot. (Although those options may be not so easy for some consumers with limited transportation, internet access or other resources.)

But closings have economic repercussions, most directly for local communities. “It’s disappointing anytime you hear of a store closing,” said Shawn Lyons, executive director of the South Dakota Retailers Association. “It’s certainly hurting not only those stores but our communities.”

An obvious and immediate outcome when a store closes is job loss. Most retail positions are low-paying, but they support workers with less education or students looking for a toehold in the labor market. Nationwide, retailers have laid off thousands of store employees over the past year. In the district, the closing of four Macy’s stores alone claimed more than 400 jobs.

So far this year, a still-healthy retail sector has softened the impact of store closings on livelihoods. Many laid-off workers have landed jobs at newly opened or expanded stores, even in states that have seen declines in retail sales. In June, over 850 retail jobs were advertised online in South Dakota’s Minnehaha County, which includes much of Sioux Falls, according to state labor market data.

Store vacancies also can hurt shopping centers, driving down rents and inflicting financial loss on landlords and investors (see Trouble at the mall).

And the prolonged vacancy of a prominent retail building or mall space can cast a pall over a commercial area, depressing property values and reducing local tax revenues. In the West End district of Billings, Mont., a bustling commercial area on the expanding western edge of the city, a number of large retail stores—Kmart, Sports Authority, home supply store Ziggy’s—have closed over the past two years. As of July, some of these stores had been vacant for months.

Wyeth Friday, director of planning and community services for Billings and Yellowstone County, expresses confidence that the vacancies will be filled in time. But he adds that, in an otherwise thriving commercial zone, a vacant store can be a turnoff for prospective tenants.

“If you have a couple of empty businesses, it starts to have an effect on the real estate of that area where people are kind of wondering, ‘What’s going to happen here, do I move in, what do I do?’”

Neither the city nor the county levies sales tax, and building owners must continue paying property taxes on vacant retail property. But persistent vacancy can trigger lower assessed valuations and a drop in property tax collections. “It’s not too long before you’d see some potential impact if the property was not filled up right away,” Friday said.

Layoffs and other deleterious effects of store closings are often more severe in smaller communities, especially those that have lost shoppers to nearby metro areas or regional competitors over the years.

Communities with limited retail demand often have difficulty drawing new stores to take over vacant retail space, said Leah Maurer, a retail investment specialist at Cushman & Wakefield NorthMarq, a Minneapolis commercial real estate firm. “If you’re in a smaller outstate market or city, the impact of a J.C. Penney or a Sears leaving is going to be greater than it would be here in the Twin Cities.”

Residents of small cities and towns are also likely to feel the loss of a store more keenly than shoppers in larger urban areas. In July, J.C. Penney closed its store in Thief River Falls, a city of 8,700 people in northwestern Minnesota. Mayor Brian Holmer said the store, the only clothing store downtown, carried items he couldn’t find at Walmart and Kmart on the east side of town. “That was my primary spot where I bought my suits and ties and stuff. That’s my loss; I’m going to have to either buy online or go into Grand Forks.”

Tuning in to the “omnichannel”

Hundreds more stores are likely to close in the district over the next year as many retailers shrink their physical footprint in a bid to cut costs and restore profitability. Further store consolidation may lead to a drop in retail employment (and full-time employment for commercial brokers due to recurring vacancies in shopping centers and malls).

However, nobody is sounding the death knell for bricks-and-mortar retail. While some retailers go bankrupt, others are responding to evolving consumer demand by shaking up the retail sales formula.

The buzzword in retail these days is “omnichannel”—the notion of leveraging every means of reaching customers, including point-of-sale marketing, social media and mobile devices. In addition to selling online, retail chains such as J.C. Penney, Target and Best Buy have introduced free in-store pickup of goods purchased from their websites.

Retailers are also striving to entice jaded, time-poor consumers into their stores by making shopping an experience rather than a chore. Target plans to remodel about 600 of its stores nationwide to transform them into what company CEO Brian Cornell has called “guest-facing hubs in a smart network,” with eye-catching clothing and home accessory displays and a separate entrance for grab-and-go items, including groceries and online orders awaiting pickup.

Ironically, some online retailers, such as Amazon and Shinola, a Detroit-based seller of upscale watches and bicycles, have opened physical outlets—a recognition that stores have their place, albeit in a different form, as showrooms for online goods.

Since 2015, Amazon has opened a half-dozen bookstores that also sell electronic devices. In May, a previously web-only retailer of active wear for plus-size women opened a store at the Mall of America in Bloomington, Minn. Juno Active President Anne Kelly said the small store has helped the firm to enhance its online brand by generating word-of-mouth advertising and providing a venue for yoga classes and other events marketed via social media. “We’ve had opportunities by being at the mall that we wouldn’t have had if we hadn’t [opened the store],” she said.

Goldberg says that many of his online retail clients are planning to do the same thing. A physical store “speaks to human nature,” he said. “People want interaction; they like seeing product and touching product and seeing what it’s all about. But the journey to get there has changed; the influences that lead them to a consumer decision have changed.”