Projected Evolution of the SOMA Portfolio and the 10-year Treasury Term Premium Effect

Brian Bonis, Jane Ihrig, Min Wei1

BOARD OF GOVERNORS of the FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM September 22, 2017

An earlier Feds note used staff models to provide a projection for the evolution of the SOMA portfolio and an estimate of the associated term premium effect (TPE) on the 10-year Treasury yield. That analysis relied on economic, financial, and monetary policy assumptions as of April 2017. With the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) announcing a change in its reinvestment policy in its September 2017 post-meeting statement, this note provides updated projections.2

SOMA Holdings

The Committee noted that effective October 2017 it will initiate the balance sheet normalization program described in the June 2017 Addendum to the FOMC’s Policy Normalization Principles and Plans. The program puts in place a policy of reinvesting a portion of maturing or repaying securities while redeeming the rest. Specifically, the Committee is directing the Desk at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York to reinvest each month’s principal payments from Treasury securities, agency debt, and agency mortgage-backed securities (MBS) only to the extent that such payments exceed gradually rising caps.

The table reports the monthly caps consistent with the Committee’s September 2017 decision and the June 2017 addendum.

Table 1: Monthly Caps on SOMA Securities Reductions

Billions $Make Full Screen

| 2017 | 2018 | Terminal Cap |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oct – Dec | Jan – Mar | Apr – Jun | Jul – Sep | ||

| U.S. Treasuries | 6 | 12 | 18 | 24 | 30 |

| Agency Debt and Agency MBS | 4 | 8 | 12 | 16 | 20 |

Source: Federal Open Market Committee

For Treasury securities, the cap will be $6 billion beginning in October and will increase in steps of $6 billion every three months until it reaches $30 billion per month; the cap for agency securities will be $4 billion per month beginning in October and will increase in steps of $4 billion every three months until it reaches $20 billion per month. The terminal caps are expected to remain in place at their maximum amounts until the Committee judges that the Federal Reserve is holding no more securities than necessary to implement monetary policy efficiently and effectively. To learn more about the operational details of how reinvestment will be conducted, see the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Statement Regarding Reinvestment in Treasury securities and Agency MBS.

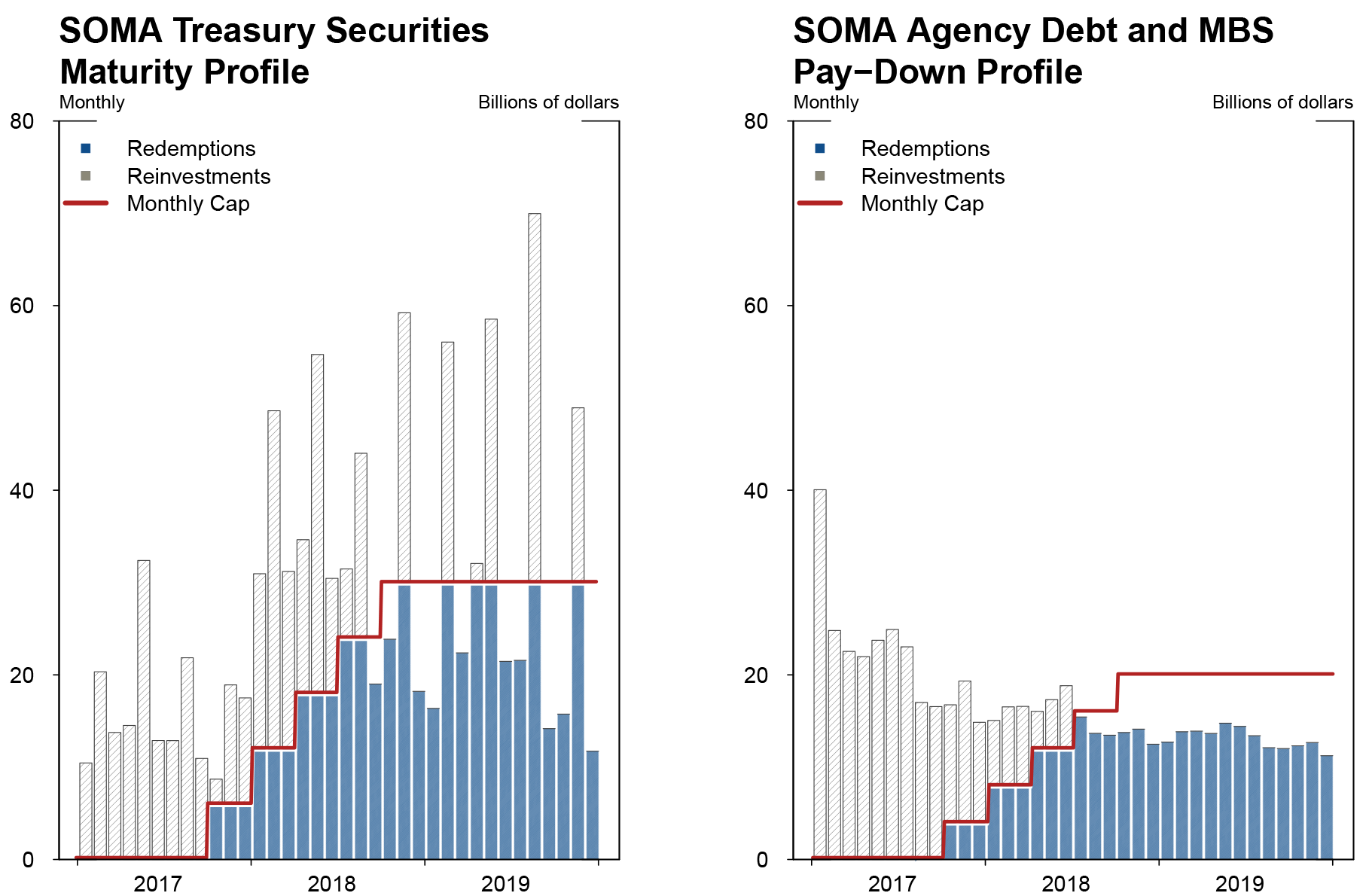

The amount of SOMA Treasury securities and agency debt maturing in coming quarters is known with certainty.3 As a result, reinvestment and redemption amounts are also known with certainty over the next two years. Agency MBS principal payments, on the other hand, reflect both regular amortization payments and unscheduled prepayments, where the latter are uncertain because of various sources of prepayments including the unknown timing of home sales and refinancing.4 As a result, SOMA MBS reinvestments and redemptions shown below are a projection. Figure 1 shows the projected monthly reinvestments and redemptions through 2019 for SOMA Treasury securities and agency securities.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York and author calculations.

In the fourth quarter of this year, $18 billion and $12 billion in Treasury securities and agency securities, respectively, are projected to be redeemed. The monthly caps are projected to bind in October through December, ensuring the gradual nature of the redemptions. In 2018, $229 billion and $141 billion in Treasury and agency securities, respectively, are projected to be redeemed. From late 2018 through 2019, the cap on Treasury securities will bind mostly in mid-quarter months; whereas, the agency security cap is projected to stop binding in the second half of 2018 as agency MBS repayments are projected to decline and there is minimal agency debt maturing.

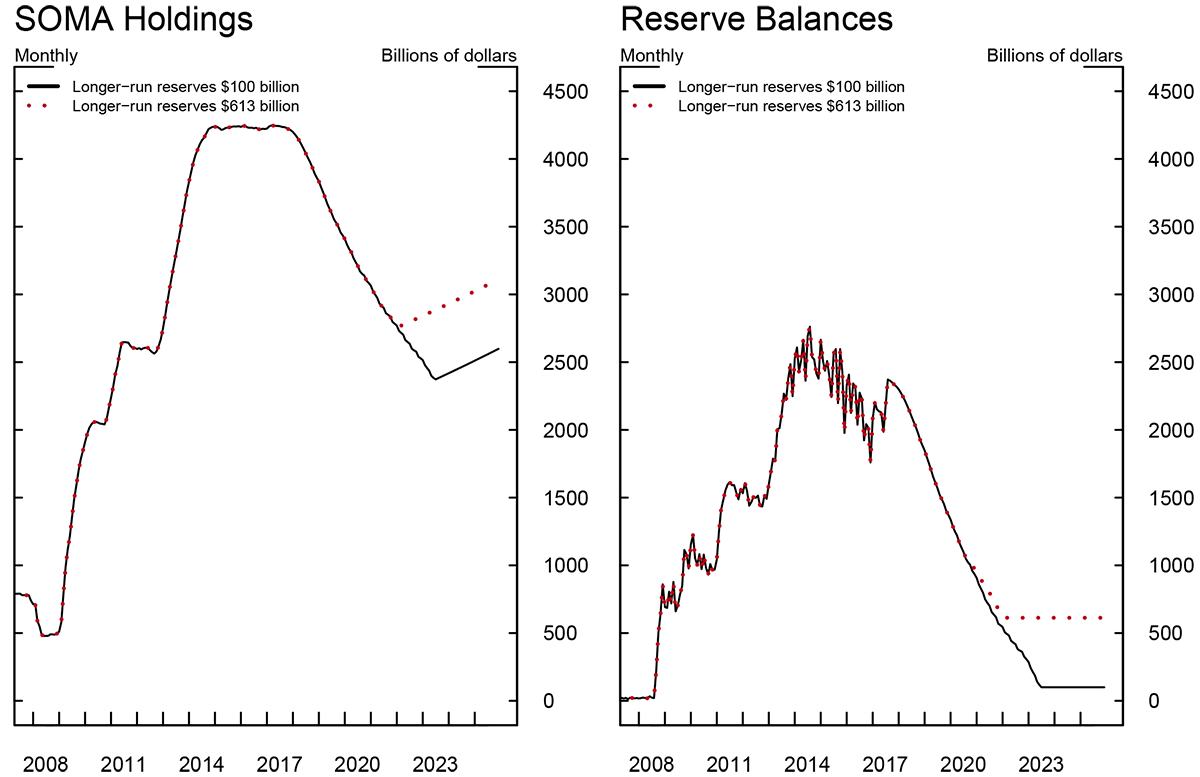

Figure 2 illustrates the projected contour of the SOMA portfolio. Normalization of the size of the balance sheet occurs when the securities portfolio reverts to the level consistent with its longer-run trend. This trend is determined largely by the level of currency in circulation and a projected longer-run level of reserve balances. There is a great deal of uncertainty about the longer-run level of reserves, which could be affected by factors such as structural changes in the banking system, the effects of regulation on banks’ demand for reserves, and the Committee’s ultimate choice of a long-run operating framework. We show two scenarios. We assume that the longer-run level of reserve balances is either $100 billion (as in our April 2017 projection) or $613 billion (the median response from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s June 2017 Survey of Primary Dealers and Survey of Market Participants).5 With longer-run reserve balances assumed to be $100 billion, normalization occurs in the third quarter of 2023. At that time, the portfolio is projected to hold about $1 trillion in agency MBS and $1.3 trillion in Treasury holdings. With reserve balances assumed to be $613 billion, normalization is moved in by six quarters to the first quarter of 2022. At that time, the portfolio is projected to hold about $1.2 trillion in MBS and $1.6 trillion in Treasury holdings.

Source: Federal Reserve Board,H.4.1 statistical release,Factors Affecting Reserve Balances of Depository Institutions and Condition Statement of Federal Reserve Banks and author calculations.

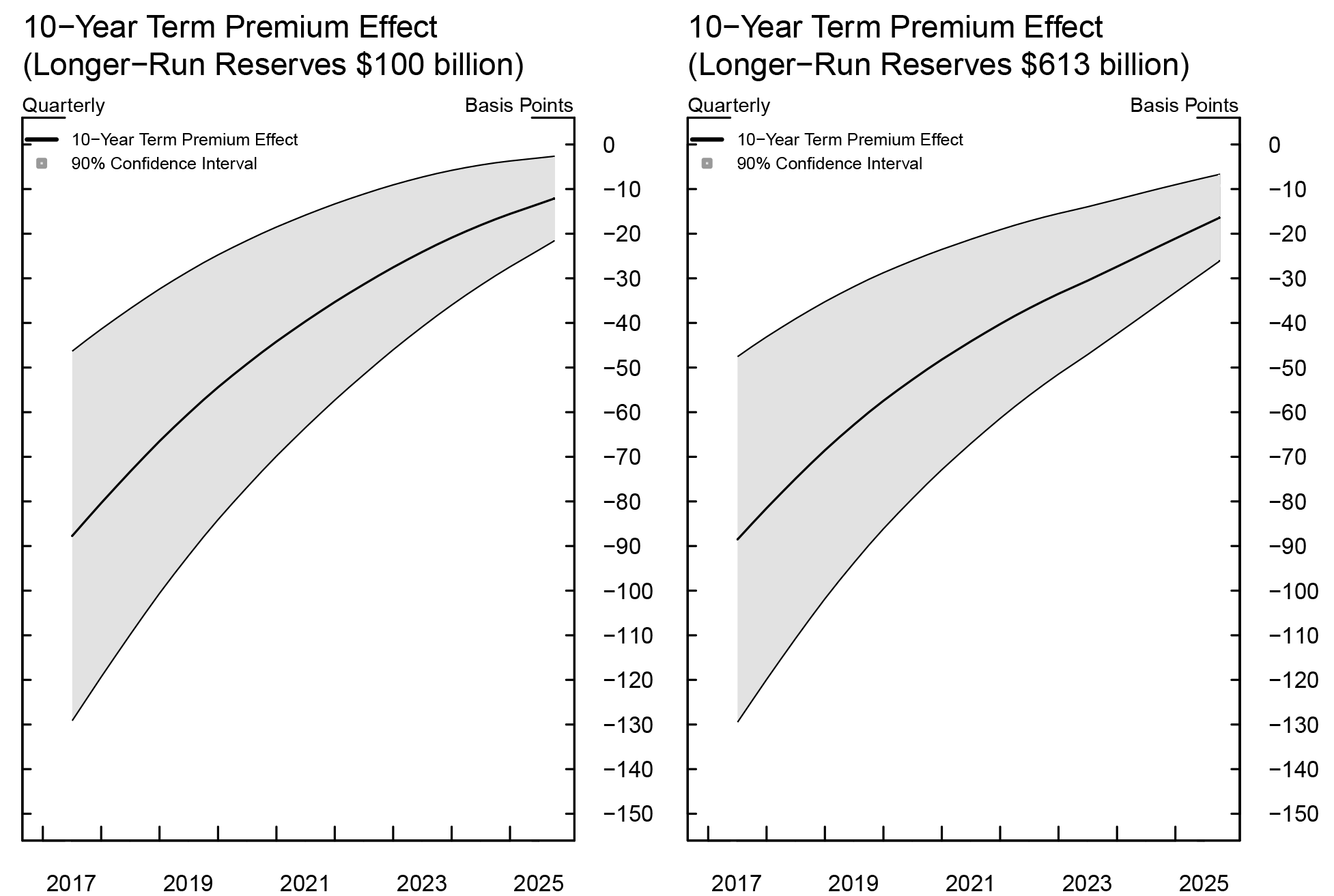

Term Premium Effect

Figure 3 shows the estimated TPE paths and the associated confidence intervals for both SOMA scenarios. As shown, the 10-year Treasury TPE paths are very similar across the two scenarios; the small difference between the estimated effects reflects the different paths for the SOMA portfolio late in the projection period as a result of the different longer-run reserve balance assumptions. At the end of 2016 the TPE is estimated to be negative 100 basis points. Roughly speaking, this implies the yield on a 10-year Treasury security would be 100 basis points higher absent the Federal Reserve’s expanded balance sheet that largely reflects LSAPs and MEP programs.6 By the end of 2017, it stands at about negative 85 basis points. This 15 basis point narrowing reflects two changes in the balance sheet: (1) the SOMA portfolio is aging and (2) redemptions have started. In 2018 the TPE wanes by another 15 basis points to negative 70 basis points.7 When the balance sheet is normalized, the TPE is still nonzero, reflecting the fact that the portfolio composition is still not what would be deemed a normal composition; see the April FEDS Note for further discussion of this point.

The confidence intervals are similar for both the $100 billion and $613 billion longer-run reserve balance scenarios and illustrate the uncertainty associated with the estimate of the TPE. For example, at the end of 2017, the upper and lower bounds of the 90 percent confidence intervals are about negative 45 basis points and negative 125 basis points, respectively. The confidence intervals narrow throughout the remainder of the projection period. Importantly, the confidence intervals take into account uncertainties associated with estimated parameters of the term structure model but not those associated with the projected paths of the Federal Reserve’s asset holdings.

Author calculations.

1. We thank Khalela Francis for excellent assistance. Return to text

2. We use the June 2017 FOMC participants’ Summary of Economic Projections for the path of the federal funds rate, unemployment, GDP growth, and inflation. Other macroeconomic variables are generated from the FRB/US model. Return to text

3. The Committee’s current operational approach to reinvesting Treasuries ensures that no securities purchased in coming quarters will mature in the next two years. See Bonis et al. (2017) “Principal Payments on the Federal Reserve’s Securities Holdings,” FEDS Notes for further discussion of this topic. Return to text

4. See Bonis et al. (2017) for more discussion of this topic. Return to text

5. See Table 2 in the July 2017 Federal Reserve Bank of New York update for the range of survey respondents’ level of reserve balances in 2025. Return to text

6. Importantly, the estimated TPE depends on the difference between the expected path for the configuration of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet over coming years and a benchmark counterfactual projection for the balance sheet that incorporates assumptions reflecting the configuration of the balance sheet prevailing before the Financial Crisis of 2007-2008. It does not take into account many other potential drivers of longer-term yields. Return to text

7. The contemporaneous TPE is initially a bit less negative in this $100 billion longer-run reserve scenario than in the April projection, largely reflecting the earlier start to the balance sheet program. Return to text

Please cite this note as:Bonis, Brian, Jane Ihrig, and Min Wei (2017). “Projected Evolution of the SOMA Portfolio and the 10-year Treasury Term Premium Effect,” FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, September 22, 2017, https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.2081.

Disclaimer: FEDS Notes are articles in which Board economists offer their own views and present analysis on a range of topics in economics and finance. These articles are shorter and less technically oriented than FEDS Working Papers.