Blame (maybe) tuition hikes, the Great Recession and lower college completion rates

by ASHWINI SANKAR

In the region as well as nationwide, escalating student debt has raised concern among educators and policymakers.

Student loans can benefit the economy by opening the door to higher education for those who otherwise couldn’t afford to attend college. Higher educational attainment raises incomes and, by fostering innovation, boosts gross economic output and productivity.

But heavy student debt can also have negative economic consequences, particularly for borrowers. Recent graduates saddled with large monthly loan repayments may lack the wherewithal to purchase a home or a car, or start a business (research by the Philadelphia Fed shows that increased student debt reduces small-business formation).

Unpaid student debt is also costly for taxpayers, who support the bulk of student financial support through federal programs such as the Student Loan Program and Pell Grants for students from low-income families. Congress is considering revisions to such programs that would raise monthly repayments, limit loan forgiveness and require colleges to pay back a share of loans not repaid by former students.

The reasons for a growing mountain of debt and rising delinquency are complex, but probable drivers include college tuition hikes, the lingering effects of the Great Recession and declining rates of students completing their degrees.

Tightening bonds of debt

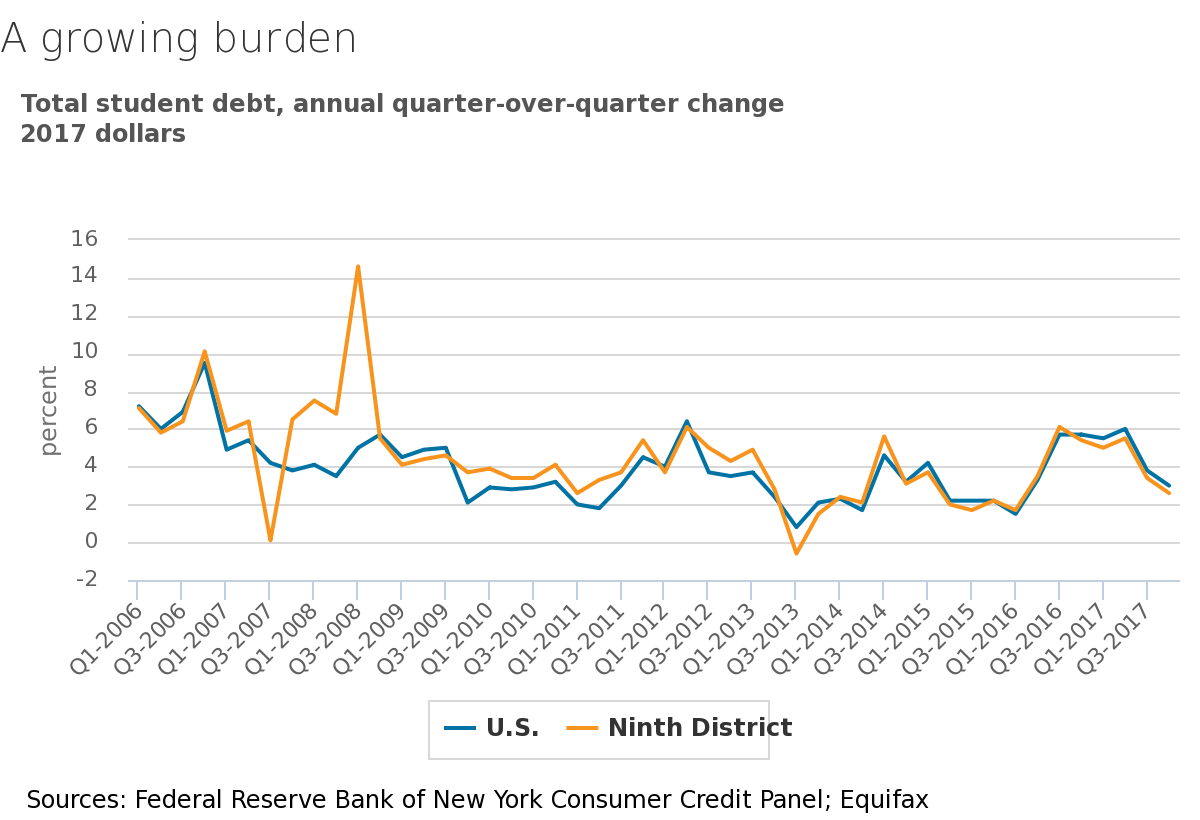

Over much of the past decade, student loan debt has risen faster than inflation, with the district and national trends closely aligned since 2014 (Chart 1). Earlier, district states on average saw greater annual increases in outstanding student debt than the nation (although sharp deviations from the district trend in 2007-08 are likely due to data anomalies).

However, on a per capita basis, the district carries a somewhat lighter student debt burden than the country as a whole. In the fourth quarter of 2017, the average student-loan borrower in the district owed almost $27,285—about $4,000 less than the U.S. average, according to New York Fed and Equifax credit data. Student debt was lowest in South Dakota—slightly over $25,000 per borrower.

During this period of burgeoning debt, tuition and fees charged by higher education institutions have increased significantly, in part because of declines in state funding.

Reports compiled by the College Board, a nonprofit organization that promotes access to higher education, show that the average cost of attending a U.S. four-year college or university increased 4 percent annually in real terms from 2007 to 2017. Meanwhile, tuition grants and discounts meant to defray the cost of college have failed to keep pace. Net prices for full-time students at public four-year institutions have increased for eight straight years, according to the College Board.

Less grant aid obliges students to bear a greater share of college costs, either by paying during their school years or by taking out loans that defer payments until after graduation.

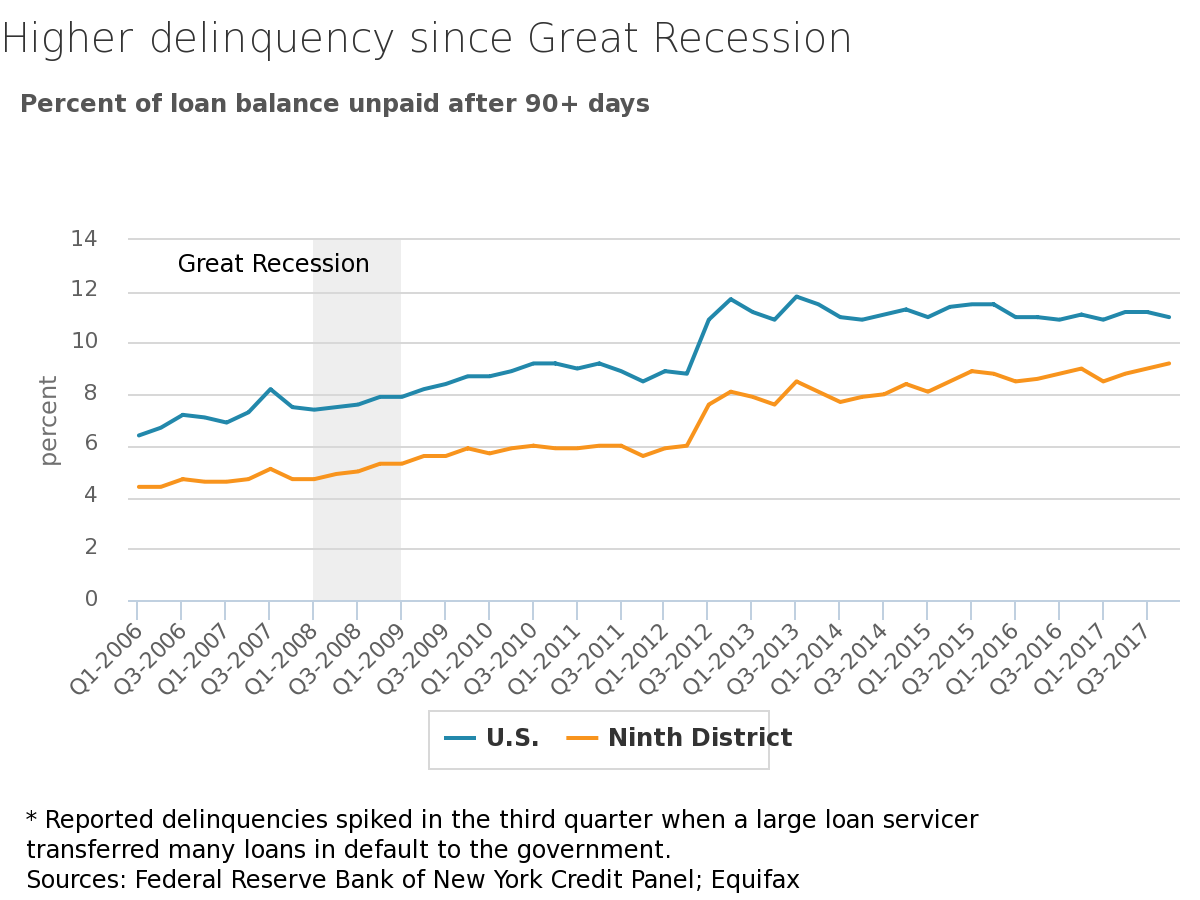

As student loan debt has increased, so have delinquency rates. Nationwide, the share of loan balances unpaid after three months exceeded 10 percent in the fourth quarter of 2017 (Chart 2); the average delinquency rate for district states was lower, but the rate has more than doubled since 2006.

In the district and in the nation, college enrollment spiked in the depths of the recession as laid-off workers went back to school to retrain or upgrade their job skills. After college, during the weak economic recovery, many of these students struggled to find jobs and fell behind on their loan payments. Since the recession, delinquencies have remained elevated, for reasons that aren’t entirely clear.

Loan delinquency varies among district states, although every state’s rate lags the national average; in the last quarter of 2017, rates ranged from 8 percent in North Dakota to a little over 10 percent in Montana.

Unfinished business

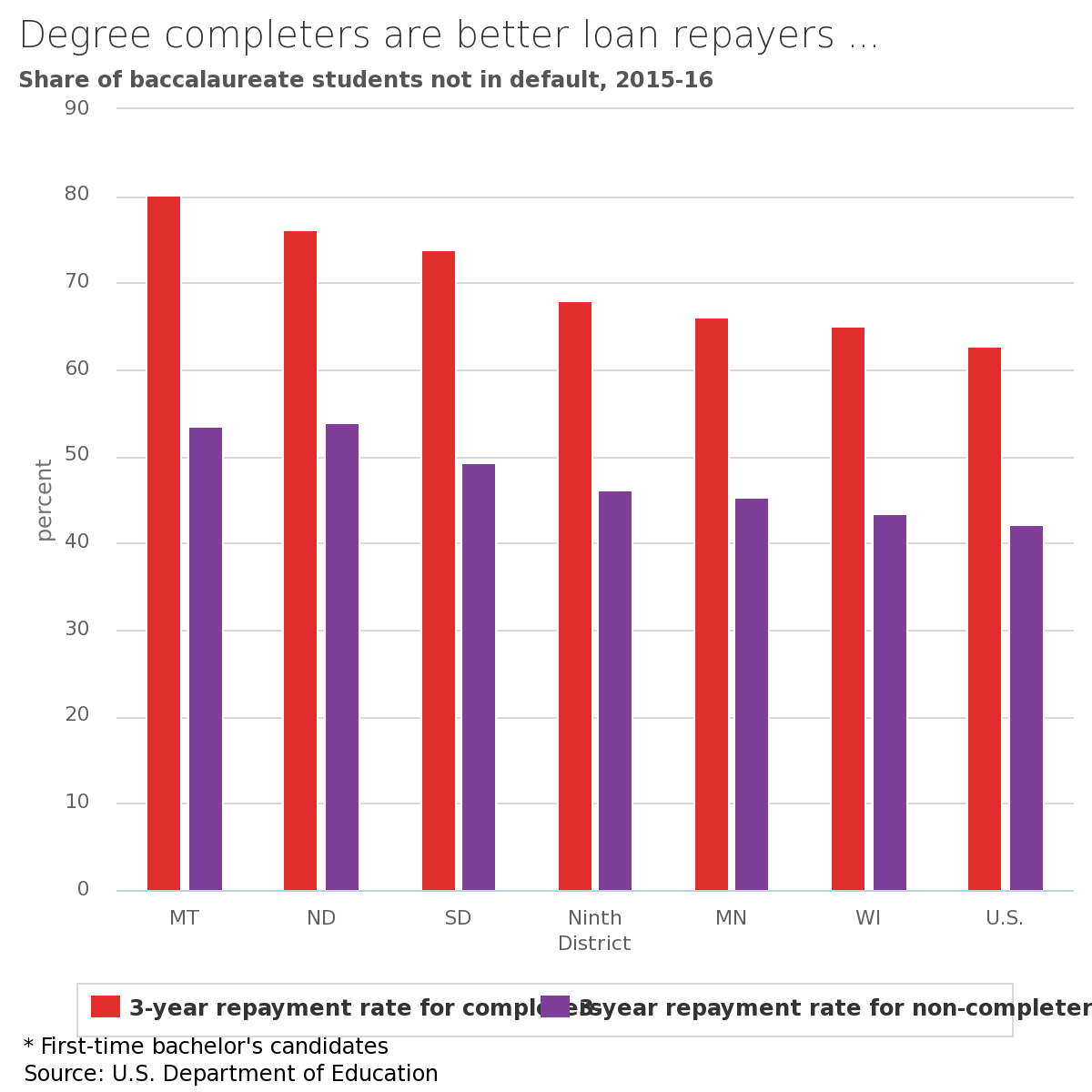

A decline in the share of college students completing their degrees may be a contributing factor to both growing student loan debt and higher delinquency.

Students who earn a degree or certificate have a better chance of landing a well-paying job after graduation, which in turn increases the odds that they will make good on their college loans. In the district, 70 percent of graduates of four-year institutions repaid their loans within three years, according to College Scorecard data compiled by the Department of Education (Chart 3). That percentage was much lower for borrowers who attended college but didn’t earn a degree.

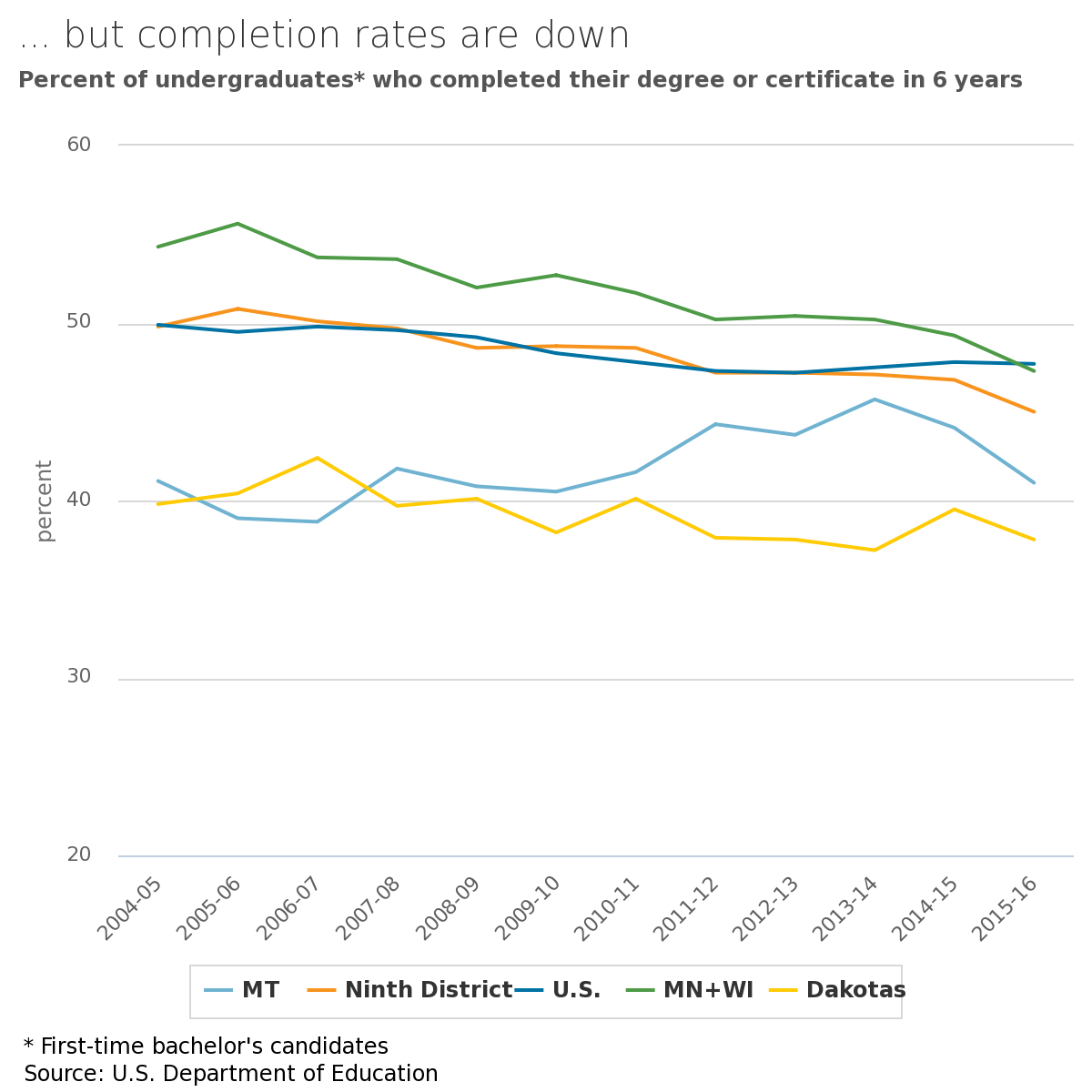

Since the mid-2000s, completion rates have dropped nationwide as well as in most district states. (Montana has bucked the trend; after a sustained rise and subsequent fall, the state’s 2015-16 completion rate remained about the same as it was a decade earlier.)

Completion rates vary by type of institution and student demographics, but no matter how the data are sliced, lower completion is associated with higher loan risk.

For-profit colleges have the worst completion rates and highest student debt levels among higher education institutions. The same factors that have eroded enrollment in for-profit colleges (see this 2016 fedgazettearticle) may also be responsible for higher proportions of students not completing their degrees and continuing to carry heavy debt loads after they leave school. These factors include increased regulatory scrutiny and competition from nonprofit institutions.

Some minority groups are disproportionately burdened by debt. Among borrowers who attended four-year colleges, those of Asian, black and Native American heritage owed the most on their student loans 12 years after beginning school, according to a Department of Education study that tracked a group of 2003 freshmen during and after their academic careers. White and Hispanic former students owed the least—less than half the amount owed by Asian or Native American students.

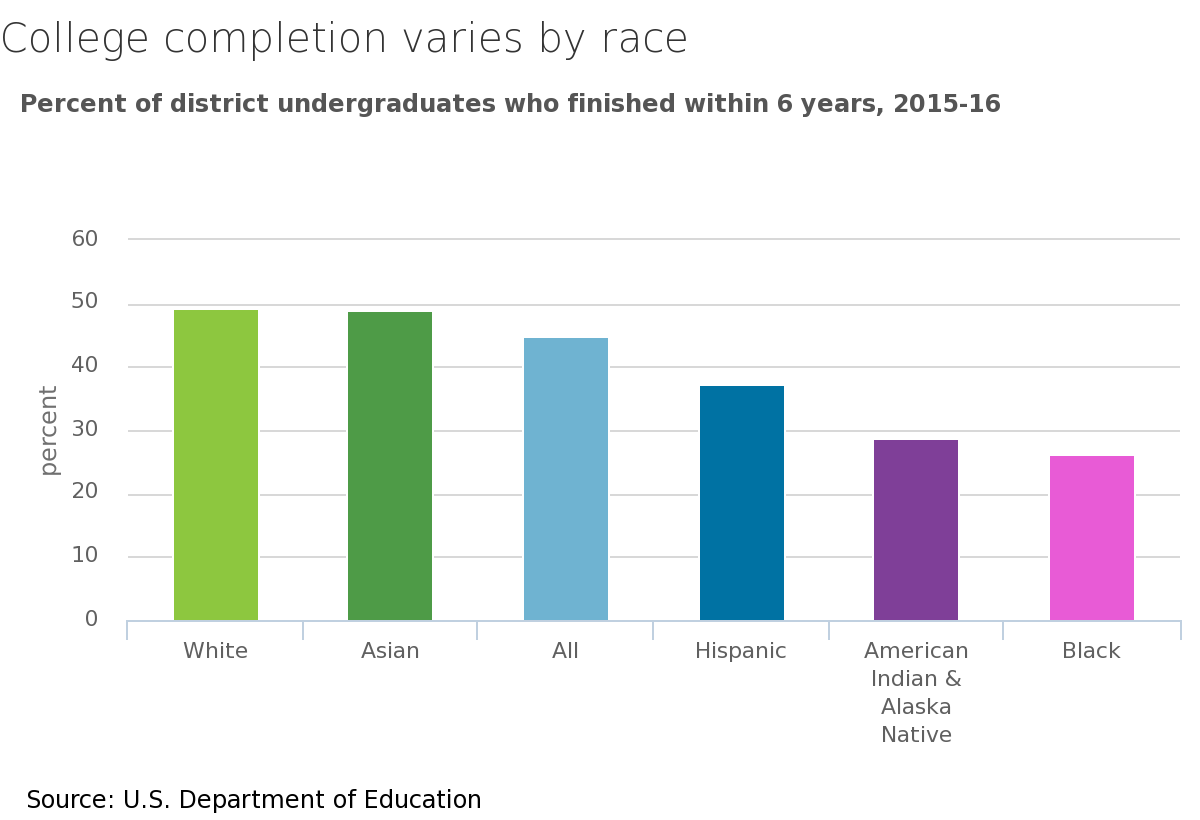

Variances in college completion rates among demographic groups (Chart 4) may explain much of this disparity in debt load. White and Asian undergraduates at district institutions finish their degrees at higher rates than students of other ethnic backgrounds, a pattern that is repeated nationally.

Given the association of college completion with repayment of student debt, government policies that encourage students to earn a degree may be part of the solution to rising student debt and loan delinquency. Federal financial assistance programs already provide incentives for students to complete college; Pell Grants, for example, require students to maintain satisfactory academic progress in order to remain eligible for funding.

A number of bills making their way through Congress that would reform student loan programs also include measures aimed at boosting college completion. A bill introduced by Reps. Virginia Foxx of North Carolina and Brett Guthrie of Kentucky would offer a Pell Grant bonus to students taking at least 15 credits per semester. Another initiative dubbed the ASPIRE Act proposes additional funding for campuses with large shares of low-income students while tightening degree-completion standards.

Community Development Financial Analyst Michael Williams contributed to this article.